Collaboration and the designer’s mindset

A look at real-world instances where design collaboration has achieved excellent results.

Many voices. (source: PublicDomainPictures.net)

Many voices. (source: PublicDomainPictures.net)

Collaboration is a key skill for designers and a critical component for healthy, functioning product teams. Design-centric organizations prize the collaborative mindset as a way to connect with customers, unite employees, break down silos, and gain new insights. Modern methodologies for the design and development of software, such as Agile and Lean UX, require close, cross-disciplinary collaboration as a baseline attribute. On a well-aligned, collaborative product team, everybody knows where the product or service is headed and has a level of buy-in, so everyone is building the same thing.

By drawing together a product team across departments and silos, regular collaboration not only enables a faster and smoother process, but also helps eliminate risk. “I think it brings folks together, but it also helps to de-risk projects and de-risk ideas [more quickly],” explains David Lemus, a consultant and former design strategist at Capitol One. “I think that’s the spirit. That’s what we’re trying to achieve when we talk about being more collaborative, in the end.” However, such a collaborative approach can be a substantial change from business-as-usual. “I think, especially in [large] organizations, we quickly think about scale, and we quickly think about swim lanes: ‘This is my area. Get to your area, and don’t cross my swim lane,’” says Lemus. “While that’s helpful for scale and clarity of the roles and job functions, it doesn’t help with being innovative and actually pushing things forward. [Collaboration] is about blurring those lines more to actually align on outcome versus aligning on individual roles.”

Collaboration skills

Several behaviors inform and support design collaboration. Let’s explore a few skills for getting the most out of creative collaborative relationships, including:

- showing unfinished work

- asking great questions

- creating context

- facilitating

- building trust

- communicating remotely

Showing unfinished work

One important tenet of collaboration is the idea that team members can and should regularly share unfinished work. It should be no surprise that this is a foundational aspect of many popular methodologies, including both Agile development and Lean UX. However, sharing ideas quickly and exposing them to other members of the team for critique and feedback isn’t easy. It requires that we let go of our illusions of reaching perfection—of our ideas and how we present them—in exchange for the very real benefit of bringing others on board with our unfinished work, whether it be a planning doc, sketch, mockup, or prototype. “I think that is an internal struggle that a lot of folks have,” Lemus says. “Changing that behavior with folks, and having that soft skill, that is [important] for anyone, no matter what at level and in what part of the organization you are.” Designers may desire only to show their very best, A+ work, but such an approach can be wasteful if that work isn’t propelling the product in the right direction. Ironically, sharing “perfect” work makes it harder for others to respond: there’s less room for critique or feedback if something looks like it’s already finalized. Allowing other team members to become early shareholders in the work can prevent it from going off the rails and save time in the long run. And, by allowing others in, sooner rather than later, you can increase the overall team IQ on the project because they will have that additional awareness. “I think of collaboration less as, ‘Let’s all produce an output together,’ and more as, ‘Let’s get smarter by sharing our ideas with each other more often and more quickly, and be OK with [initial ideas] being at the C+ level,” says Surabhi Mahapatra, a design consultant for such clients as Spotify.

Asking great questions

When it comes to design leadership, the larger frame is quickly shifting from commanding to coaching—constantly asking great questions and not supposing that you have all the answers. And, on a strong, collaborative team, leadership can come from anyone. This coaching style of leadership helps clear the path for the team and nourishes new ideas. “You do not have the answer anymore just because you grew up in the ranks of a big organization and [have] been there 20 years,” says Lemus. “Everything has changed. The only role you have now is being a good question asker and creating the right conditions for your teams to go explore and go ask really thoughtful questions. … That is your role as a leader.” This is a culture shift from the command-and-control style of many large organizations. It’s about admitting that the right solution, the right answer, may yet need to be discovered.

Creating context

Creating context—group knowledge and awareness around progress toward shared goals—can, in a small team, be the natural outcome of co-location or regular check-ins. But this can become increasingly challenging at scale. Floris Dekker, product design director at Etsy, describes how their team developed a shared context across the company’s growing design organization: “It’s really about making sure people actually know what everyone’s working on. I think that’s a step beyond just sharing or just making sure it’s transparent.”

The deluge of information that can come from open team communications can be overwhelming. “We’ve tried to do it digitally with a giant feed of all the work that’s happening,” says Dekker. “But there’s this saying, which kind of stuck with me: ‘Content is overrated.’” Having access to shared design work does not guarantee a shared understanding.

The Etsy design organization has tackled this challenge by being hyper-focused on creating context for the larger team. “We have one meeting called ‘Design Lightning’ where everyone comes together and just shares the work for a minute or two,” says Dekker. “Everyone gets to see all the work that’s happening at that point in time.” This gives the team a snapshot of the relevant work without creating extra noise. “Basically, you have all the context of all the work that’s going on,” says Dekker. “If someone’s working on something you should be talking to them about, going to that meeting will empower you to make sure you’re designing toward the same shared goal.”

Facilitating

As collaborative design becomes a larger organizational function—not just limited to a few individuals or even the design department—facilitation is becoming an important, even critical, skill. Enabling a collaborative mindset can be difficult. “Honestly, one of the biggest [barriers to open collaboration] when working in tech is expertise,” says Naveen Raja, a design thinking consultant. “You have people who have been working in the field for 20 or 30 years, and definitely are experts. But then [they think] their opinion is the only one that matters, and that in itself is very frustrating. Sometimes I joke that I’m like a glorified kindergarten teacher because I’m breaking up two very smart people [who are] just arguing [about] who’s smarter.”

“What makes a good facilitator is being able to read those personalities off the bat and say, ‘All right. I understand you’ve been here for 20 years and you’re an executive, but the whole point of this workshop is that you need new fresh ideas,” says Raja. “You get that by having a diverse number of viewpoints and weighing out which ideas are good and bad, not you saying what we’re going to do and everybody begrudgingly kind of going along.’ That’s where that misalignment happens.”

“A designer makes a great [collaborator] because they’re used to communicating, whether that’s visually or whether that’s verbally. Those are skills that anybody, in theory, can learn,” says Raja. “But through design education, you learn how to do critique. You learn how to talk about work and be vulnerable. You learn how to pitch your work. … These are skills that we pick up through our education or through our career, while others, maybe in different fields don’t get that soft skill set.”

Building trust

Cross-disciplinary collaboration across an organization can be a catalyst for culture change, altering the expectations for how people work together and communicate. When we become comfortable seeing the world through a consumer-focused lens, being concerned about customer experience, and advocating for customer-centricity in product design, this mindset can extend beyond that of customers to employees and the overall team. Of course, such norms can be at odds with those embedded in industrial age organizations. But, clearly, times have changed and we’re entering a new era, where customers and even employees have a voice that companies are forced to consider. “Imagine a world where everybody has incredible trust built on the team because we’re good question askers, and we’re empathic toward each other,” says Lemus. “That means we can bring our best selves to work, and now we can have that radical candor, and we can have growth and feedback. Because, ultimately, I’m being human first.”

Communicating remotely

In-person collaboration is a high-fidelity activity that can be difficult to replicate within the constraints of screen sharing, conference calls, and synchronous and asynchronous software tools. How do we manage collaboration between teams that are not in the same place?

“I was just doing a project with Spotify and I was being asked to share insights in a new way that I hadn’t done previously, which was more in real time,”says Mahapatra. “I [was in] Boston [and] the main stakeholders were in Stockholm, Sweden. So, we ended up using Slack quite a lot, and I really liked it. I was surprised. It was wonderful because what ended up happening [was] senior level stakeholders were able to see photographs, insights, things I was coming up with from the field through a Slack channel within 24 hours of me conducting the research. I think that was really critical because they were then able to get interested in my process earlier on.”

“Remote collaboration works, but it takes more effort,” says Raja. “It’s like a long-distance relationship. Proximity makes everything easier, but good outcomes can happen either way. There are a lot of really great companies that are completely remote, [like] InVision [and] Buffer.”

Attention to interpersonal engagement is key to successfully collaborating at a distance. A common mistake is to treat remote team members as if they have similar access and awareness as the team members who are local. Since the fidelity of online communication, no matter what the specific medium, is much lower than a face-to-face interaction, it requires tailoring the collaboration to that remote channel. Big meetings can be a big no-no. For instance, large-scale team Skype calls can be problematic, unless they’re tightly structured. “It’s impossible to engage with that,” says Raja. “Even in a room, only a very well-spoken person can engage with 15 people simultaneously. When you utilize remote collaboration, you should be trying to do it one-to-one or maybe like two-to-one. … Once you start having 5, 10, 15 people all dialing into Skype calls, you don’t know who’s talking. You don’t know what the objective is.”

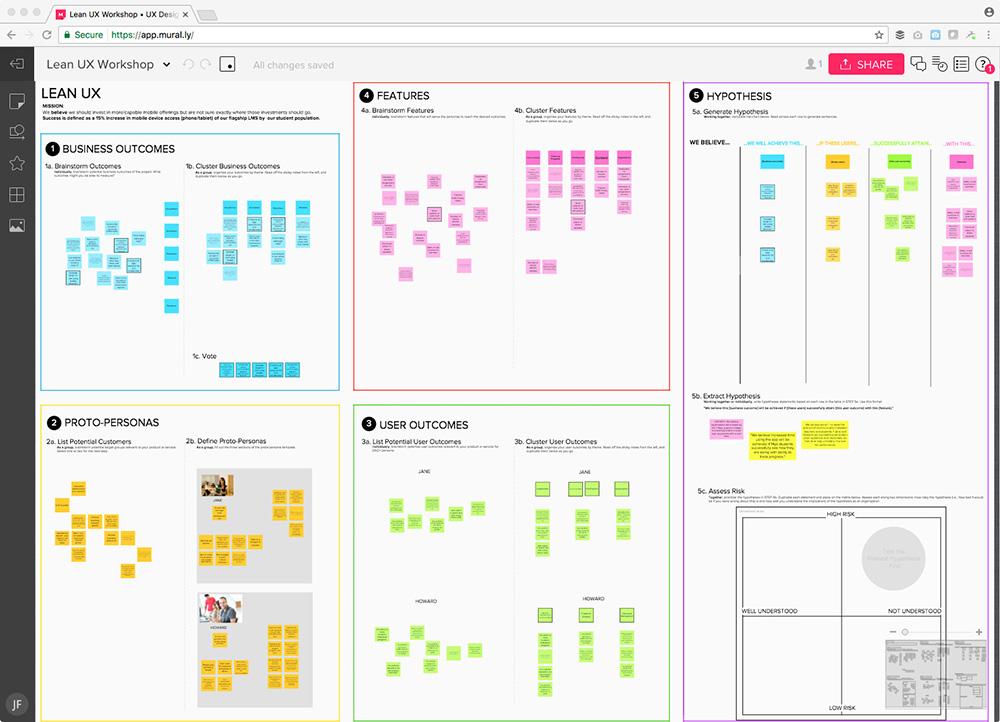

When you have team members scattered across the world, in addition to working asynchronously, it can be important to find some overlap in the workday where the group can work together, even if it’s only for an hour or so. Using synchronous tools like MURAL—a SaaS product enabling brainstorming and remote design collaboration—or even Google Docs—which allows for multiple authors to see edits as they happen—can help small remote teams coalesce as they work together in real time.

Design collaboration in action

Blurring the boundaries between disciplines—bringing together designers, engineers, business stakeholders, and users through collaborative work—can achieve outsized results. Let’s take a look at a few examples of where collaborative efforts have achieved successful outcomes in real-world projects.

Wind Farm Management

How do you quickly create an effective system for expert, technical users? Last year, Oakland, California-based digital product and system design consultancy Futuredraft engaged on a project to design a software system that would allow engineers to manage wind farms more effectively. Wind farms can be made up of hundreds of turbines, all of which need to be monitored and maintained on a regular basis.

The Futuredraft team was able to create a prototype that tested well very quickly, by working directly with the system users to co-design the solution. “We had them sketching out how they would approach certain problems,” says Jorge Arango, partner at Futuredraft. The expert users—wind farm field engineers —weren’t at all familiar with design collaboration or co-creation. Their day-to-day job required them to work onsite at wind farms in remote locations, moving from site to site—sometimes far beyond the reach of even cell phone coverage. “If you get [expert users] in a room and you set the right conditions, and you make them comfortable, and you ask the right questions, and reflect the answers back to them, that sparks a conversation that allows these things to emerge very quickly. That is something that could only [come together] as fast as it did in a collaborative way.”

This facilitation and co-creation technique enabled Futuredraft to draw out from the expert users’ ideas for both workflow process as well as the interface. “You’re trying to get folks to understand the world through a different lens,” says Arango. “The lens has to do with making things. … [Picturing] yourself interacting with something is very different than talking about how you would interact with something.” By enabling expert users to engage directly in design techniques like sketching, the Futuredraft team was able to rapidly reach a successful product design.

IBM X-Force Red Portal

The IBM X-Force Red portal provides a centralized system for managing enterprise security testing programs by enabling a single view into vulnerabilities and allowing users to schedule security tests on-demand, see test status, and review findings. Naveen Raja describes the initial collaborative workshop that helped fuel the product and system design: “We had 26 people come from all over the United States and the world to Austin, Texas. I ran a workshop to redesign how pen testers and ethical hackers interact with customers,” explains Raja. “They came [to the workshop] saying, ‘We know exactly what we’re going to build. We just need you to help us flesh out the design.’ What we left with was something completely different that focused on user needs.”

A collaborative mindset was required from the group to break out of the assumptions that had already congealed around the project. While the workshop began with certain expectations around the “right” potential solution—the creation of an automated analyst or virtual security assistant—by asking great questions, and keeping a focus on the users, Raja and the IBM X-Force Red Portal team were able to discover and find solutions for the real problem set. The team peeled back the layers to learn the reasons why security analysts were not performing, and discovered that the analysts didn’t feel comfortable or confident interacting with the customers. “Then you shift,” says Raja. “And you see the direction changing toward solving a real problem, which [was], ‘We need to better train and hire our security analysts in order to deliver a greater user experience to our customers who rely on these people to protect their companies.’”

Adopting a collaborative mindset

It’s clear the collaborative mindset is increasingly valuable for today’s design work that must draw upon many different kinds of expertise. There’s no doubt that a shift toward collaborative organizations, with a strong focus on the customer, has already started. But the journey from silos to well-functioning, multi-disciplinary teams will continue to be an adventure. How do we get there? Well, let’s collaborate—what do you think?

Resources

Interested in exploring more about design and collaboration? Here are a few recommended resources:

Collaborative Product Design—working better together for better UX, by Austin Govella

Opening Doors to Teamwork and Collaboration—4 keys that change everything, by Frederick Miller and Judith Katz

Integrating Lean UX and Agile, by Jeff Gothelf and Josh Seiden