Designing culture

This report examines how your organization can use behavioral science to design a workplace culture that supports creativity, collaboration, and innovation among your employees.

Bonsai living plant. (source: FSTOPLIGHT on iStock)

Bonsai living plant. (source: FSTOPLIGHT on iStock)

Humans are the biggest driver of growth, differentiated products, and profitability. Your workplace environment significantly affects human behavior. Behavioral strategy is the practice of strategically arranging environmental influencers to drive the behaviors that deliver desired results. Environments designed with behavioral science can be used to support creativity, collaboration, and innovation. They can be used to support execution and productivity, as well as improve attraction and retention. Your workplace environment reinforces brand identity, aligns the efforts of teams, and drives increased revenue.

This report outlines the framework of a behavioral strategy approach, looking at attraction and retention as one example of a business problem that can be resolved using behavioral strategy. At the end of the report, we’ll look at a case study where workplace success directly affected revenue growth.

Understanding the Behavioral Strategy Framework

Herb Simon, Nobel Laureate, American political scientist, economist, computer scientist, sociologist, and psychologist, authored the clearest framework for the practice of behavioral strategy. In 1990, he published a theory of bounded rationality, where using the analogy of a pair of scissors he argued that decisions were driven both by the limitations of the human brain and by the structure of the environment those decisions were operating within (see Figure 1-1):

Human rational behavior is shaped by a scissors whose blades are the structure of task environments, and the computational abilities of the actor.

Herb Simon, “Invariants of Human Behavior,” Annual Review of Psychology #41 (1990)

This model clarifies what behavioral science practitioners have known for years, allowing that there are only two ways to modify behavior: change the person or change the environment. The latter is significantly easier.

Applied behavioral strategy for most of its history has focused on driving buying behaviors in retail and reducing negative behavior in prisons. However, in today’s highly competitive landscape, humans are not just cogs in a machine but are the machine itself and so the attention of behavioral sciences has shifted to the workplace.

Applying Behavior Strategy to Today’s Workplace

Teams are now the fundamental unit of organization, which makes behavioral sciences in the workplace a new and challenging discipline. If a company wants to outstrip its competitors, it needs to influence not only how people work but also how they work together. As a result, much of the new behavioral research is focused on teams in the workplace and many of the previous prison and retail behavior studies are being applied and tested in organizations. We now know that the same nested groups that reduce behavior challenges in open prison units can be used to normalize behaviors in any organizational team in order to support collaboration. We now know that the retail concept of functional inefficiency can be used to introduce diversity and adjacent possibility in order to drive innovation. Just as we could measure in dollars the buying impact of putting milk in the back of the grocery store, we can measure in dollars the results of an environment designed to influence behaviors in the workplace.

Relationships are more likely to develop based on brief, frequent, passive contacts made going to and from regular locations than develop based on shared attitudes, values, and beliefs.

L. Festinger, S. Schachter, K. Back, “The Spatial Ecology of Group Formation” (1950)

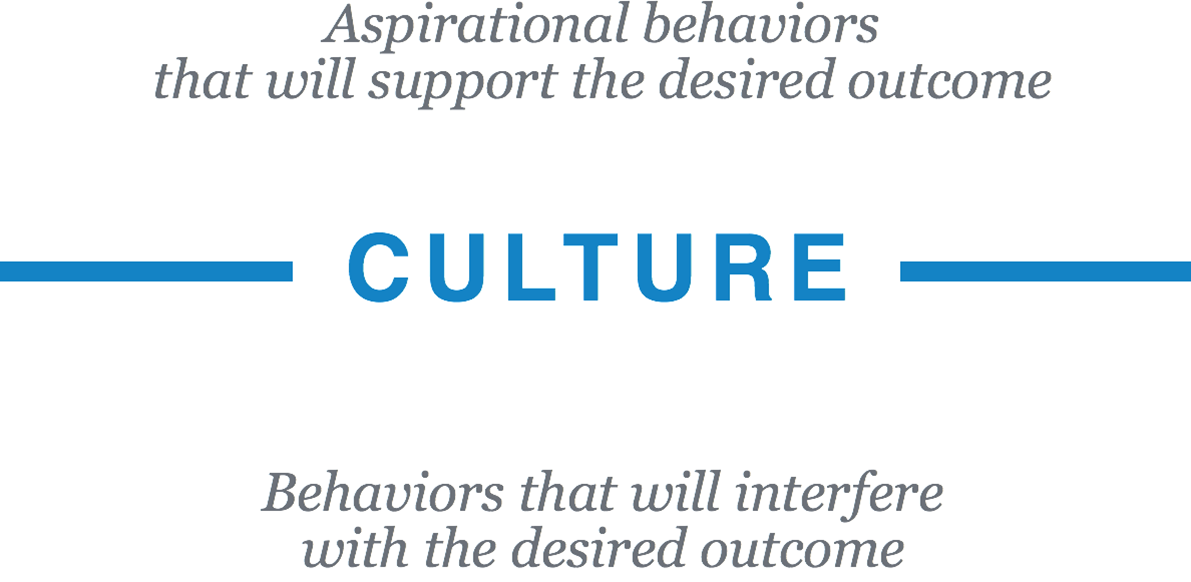

I propose that we agree with the seemingly obvious premise that individual behavior drives individual results. Collective behavior, usually called “culture,” drives collective or organizational results. Environment influences behavior, collective behavior creates culture, and culture drives results. By following this thread of behavior backward from our desired result, we can significantly impact performance (Figure 1-2).

Getting clarity around those desired results is a critical part of the process. Too often environment projects are completed without understanding the behavioral connection to critical business issues, leaving potential value untapped.

Example 1: A Biomedical Engineering Company and Driving Results after Outsourcing

Medtronic is a biomedical engineering company with an Electronic Division in Tempe, AZ. It had outsourced all but the most specialized manufacturing, resulting in a loss of two-thirds of its workforce. My company was hired to advise Medtronic Tempe Campus (MTC) on its real estate strategy: what could it do with eight buildings on 32 acres that it now did not need? However, there were two real business challenges that were uncovered during the discovery phase of our work. These challenges could be at least partially solved by the real estate decisions we would make:

- Proving the value of the remaining operation to corporate leadership

-

The division was originally a specialty manufacturing plant and now with most of the manufacturing gone, they needed clarity around who they were in order to market themselves to Medtronic corporate.

- Hiring a diverse workforce

-

Older workers were the significant majority, with an average age in the low 40s. This was a challenge both for engaging new ways of working and for knowledge transfer as that generation approached retirement.

Although Medtronic corporate was clear about its brand and direction, the tired manufacturing spaces of the division at MTC said nothing about the brilliant engineers and researchers who were core to MTC’s offering. The company had hundreds of patents and through their work and some truly innovative collaboration practices were breaking ground in providing electronics for medical implants. Yet as visitors entered the lobby and viewed the 1980s era oak-framed exhibit case of inventions, or as potential hires toured high-walled cubicle warrens (gray cubicles, on gray carpet, with gray walls), or as potential customers toured through the labs and factory, walking across 300 yards of treeless parking lot in 120-degree Arizona heat, there was little visual evidence of the brilliant work that was happening at MTC (unless you stumbled on it).

That lack of alignment between the visual environment and the reality of MTC’s offering combined with the extreme downsizing that left most buildings empty, created a loss of confidence in their own understanding of their value, and exacerbated trepidation as to how MTC would move into the future. My company was first approached by the MTC tech council, a group of senior employees with advisory responsibility to the division’s general manager. These employees knew that MTC needed to discover again what kind of company it was to present a clear message to customers, potential hires, and Medtronic corporate. This group also realized that their new hires demanded a new kind of collaboration. We presented these findings to the general manager and were then retained to roll those efforts into a larger real estate strategy that could be handed back to their facilities group for implementation.

The solutions to these challenges would be implemented over time and so our charge was to create a road map that identified a few immediate projects but also lay out a multiyear change plan:

- A clear visual representation of the MTC value offering

-

For example, transforming that long walk across the parking lot between research building and factory and turning it into a reinforcement of MTC’s intellectual prowess by creating a shaded walk that was lined with individual pavers, of which each would be engraved with one of the hundreds of patents from MTC’s work.

- Increase diversity

-

This was initiated by supporting connections between researchers, engineers, and the remaining specialty manufacturing. In his book The Difference: How the Power of Diversity Creates Better Groups, Firms, Schools and Societies (Princeton University Press), researcher Scott Page very clearly establishes the problem-solving power of diverse groups. By providing environment vehicles (spaces and programs) to support this at MTC, we drove better problem solving and innovation.

- Attract and retain younger workers

-

This would include, but not be limited to, a physical space transition plan that would find balance, acknowledging the need for focus in a private cubicle and balancing an open office collaboration.

The work that my company did for MTC was just a few steps into the road map, but imagine what would have happened had we simply made decisions about what to do with those eight buildings and 32 acres without considering the larger business issues. The critical path in using environment to drive behavior is to be clear first on the desired results. In this case, it was the need for clarity around value proposition and the need to attract and retain a wider demographic. Once those goals were clearly defined, we could design the culture that would support those results and then design the environment that would support that culture.

Intentionally Designing Culture

So how do we design culture? The simplest definition of the collective behaviors that define culture that I have seen was put forward by Chris McGoff in his book The Primes: How Any Group Can Solve Any Problem (Wiley). He says that culture is, very simply, the line between behaviors that are tolerated and those that aren’t. I find that framework useful, as we can move it into solution space and design culture by defining the behaviors we aspire to (see Figure 1-3). This will then support the business results we need and identify those that interfere with the desired outcome. The path to the results we want comes from comparing this aspirational picture of culture with our current state, the behaviors we tolerate, and mapping the difference. We can use behavioral science to design the path from a culture that does not support desired outcomes to one that does.

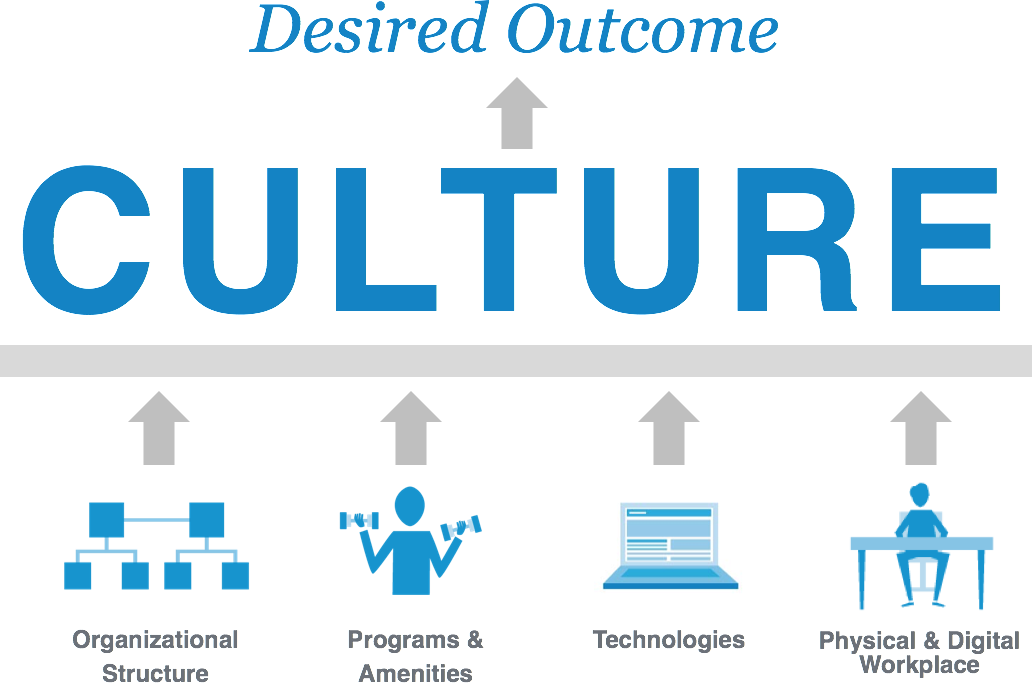

If culture is a collection of behaviors that result from decisions made by individuals and that decision making is then affected by its environment, I propose that there are four main levers available that can be used to create an environment that will drive culture:

- Organizational structure

-

Hierarchies, teams and team size, lines of reporting, and remote/local workforce distribution

- Programs and amenities

-

Everything from free food in the kitchen, to compensation strategies, to recurring meetings

- Technology

-

Digital and mechanical tools and systems that support our work processes

- Digital/physical space

-

This is the one seamless area where we work, connect, and collaborate, creating adjacencies, awareness, and opportunities to know what you didn’t set out to know

Each of these levers is part of the environment that influences behavior choices that we make. And each will enable or interfere with the environment that is needed to create the desired behaviors. Environment is not just the physical/digital workplace but also the programs, technology, and organizational structure, all working with our brains as the second blade of the scissors to drive decision making and behavior (Figure 1-4). That environment can be crafted to drive the culture that leads to the desired outcome.

Using Behavioral Strategy for Attraction and Retention

I would like to take you through some ways that environment can impact attraction and retention as a way of illustrating the value of a behavioral approach. Let’s begin by looking at the example of one basic behavioral driver that influences our decision to join an organization. Dr. Rebecca Bigler, director of The University of Texas at Austin’s Gender and Racial Attitudes Lab, has done a number of experiments with preschoolers and colored T-shirts. In one, she took a classroom of four- and five-year-olds and put half in red T-shirts and the other half in blue T-shirts. The children wore these colored T-shirts for three weeks, but teachers were instructed not to notice or mention the colors in any way. At the end of the three weeks, children were asked to evaluate the skill, abilities, characteristics, and intelligence of each group. When asked “How many blues are nice?” kids wearing red were more likely to answer “Some” and kids wearing blue would answer “All.” When asked “which color team is better to belong to?” kids almost universally answered with their own color.1

Although this experiment was conducted with preschoolers, as adults, we still recognize the dress and environment of those we perceive to be like us and we credit that group with being smarter, more innovative, more trustworthy, and more capable of success. We are naturally drawn to be part of groups that are like us. If you do a web search for tech founders, you will find endless images of black T-shirts and jeans. If you search for corporate leaders, you will find suits and ties. If you want to hire tech founders or corporate leaders, you need to create an environment that they will recognize as their own, fitting the symbolic colored shirt of “their” team. Your potential hire waiting for the interview will decide by looking at your website and your reception area whether or not your company wears the same color they do and based on that, whether they trust you, whether they believe your company will be successful, and whether this might be the place they want to work. They will decide that long before they ever meet you.

Towers Watson (a global professional services firm with a focus on people and risk management) generates a research-based workforce study every other year. Its 2014 study surveyed 32,000 employees from large and mid-sized organizations in 26 markets globally. In that study, it found that the top driver of attraction and retention was salary, which, of course, can be manipulated as base pay plus bonus to create an environment to drive behavior. The next four drivers can be directly impacted by design strategy: job security, career advancement opportunities, learning/development, and challenging work.2

Job security may seem an odd match with environment design strategy, but if we look at research focused on the factors that create a feeling of security, we can tease out behavioral strategies to be used for decision making in the work environment. In essence, a sense of job security is directly connected to perceived control:

(Research) results indicated that personal, job, and organizational realities associated with a perceived lack of control are correlated with measured job insecurity. Job insecurity in turn leads to attitudinal reactions—intentions to quit, reduced commitment, and reduced satisfaction.3

So, if a sense of job security is a critical factor in attraction and retention, and that sense of security is connected to perceived control, then it becomes a matter of determining how we might use the physical/digital environment to increase the perception of control. The myriad of ways to make that happen are numerous enough to warrant another report in itself, but it will suffice for this overview to simply point out that it is possible through allowance of choice and empowerment to use both the physical and digital environment to increase the perceived level of control, increasing a sense of job security, and thereby increasing retention.

When working on retention, we should also consider the symbolism attached to physical environment cues. The visual environment communicates just as strongly as what is said and written. Career advancement opportunities need to exist, but also be apparent, as when dealing with people, perception is more important than reality. Employees must perceive that advancement is easily available for those who produce results. In a typical old-style office layout with the C-suite on the top floor and a private lunchroom, advancement seems more difficult. It looks like only the rarified few make it into those suites and this is a disincentive for most. The visual cues communicate a stiffly hierarchical structure that is difficult to breach.

According to the Towers Watson study, employees actually want growth (people, projects, and opportunities) more than promotions and it is important that the physical environment communicates the availability of that growth as well. Historically, a move from cubicle into private office meant a promotion. If you see a friend unpacking a box in their new private office, you automatically offer congratulations on the promotion. However, if growth opportunities are more important than promotions, then the private office as a perk has less power than perhaps an assignment to head up development of a cutting-edge idea, leading a team in its own project room. Today’s equivalent of unpacking in a private office is seeing a friend assigned to their new team room or launching a Slack channel. Growth and learning as a retention motivator imply the needs for different kinds of rewards and different spaces, both physical and digital, to support those rewards.

Before we move to the next example in our attraction retention behavioral tool kit, let’s talk about the connection between retention and sustainable engagement. Attraction and retention have a long history of research that has evolved as the workplace has evolved. The earliest research in this area focused on the question “Do I like my work?” and then subsequently “Will I stay at this job?” In recent history, as companies push to find areas of greater productivity, employee surveys have focused more on questions that reveal a level of engagement. Today, as margins become tighter and competition increases, the survey questions increasingly focus not just on attraction and retention, but also, more importantly, on sustained engagement. Are employees engaged in a sustainable way that will make them want to work at maximum productivity for all of the years that they work for your company? Research has shown time and again that an engaged employee base is easier to retain and that high levels of sustainable engagement can be directly attributed to a company’s profitability.

The Towers Watson study built on this, identifying two key factors that take an employee from being engaged to sustainably engaged. These factors are having the employee be enabled and energized. Being enabled includes supporting the employee’s productivity in multiple ways. Being energized includes a broad sense of health and well-being, managed stress, and social supports.

Example 2: A University’s Expensive, New, Underperforming Building

In August of 2013, the W. P. Carey School of Business Graduate Programs moved into its beautiful new building, McCord Hall. The project was a $57 million, 129,000 square foot, LEED-certified masterpiece designed to support new kinds of learning with more than 50 team rooms, classrooms, lecture halls, and a large new open office area for the graduate programs staff. It was an amazing building for the students, but for the staff who ran the graduate programs, the new space was not working. Leadership of the graduate programs group came to me a year later, because the staff still wasn’t settled in and the Graduate Programs now had the problem of an alarming staff attrition rate—the building was not working as well as it could.

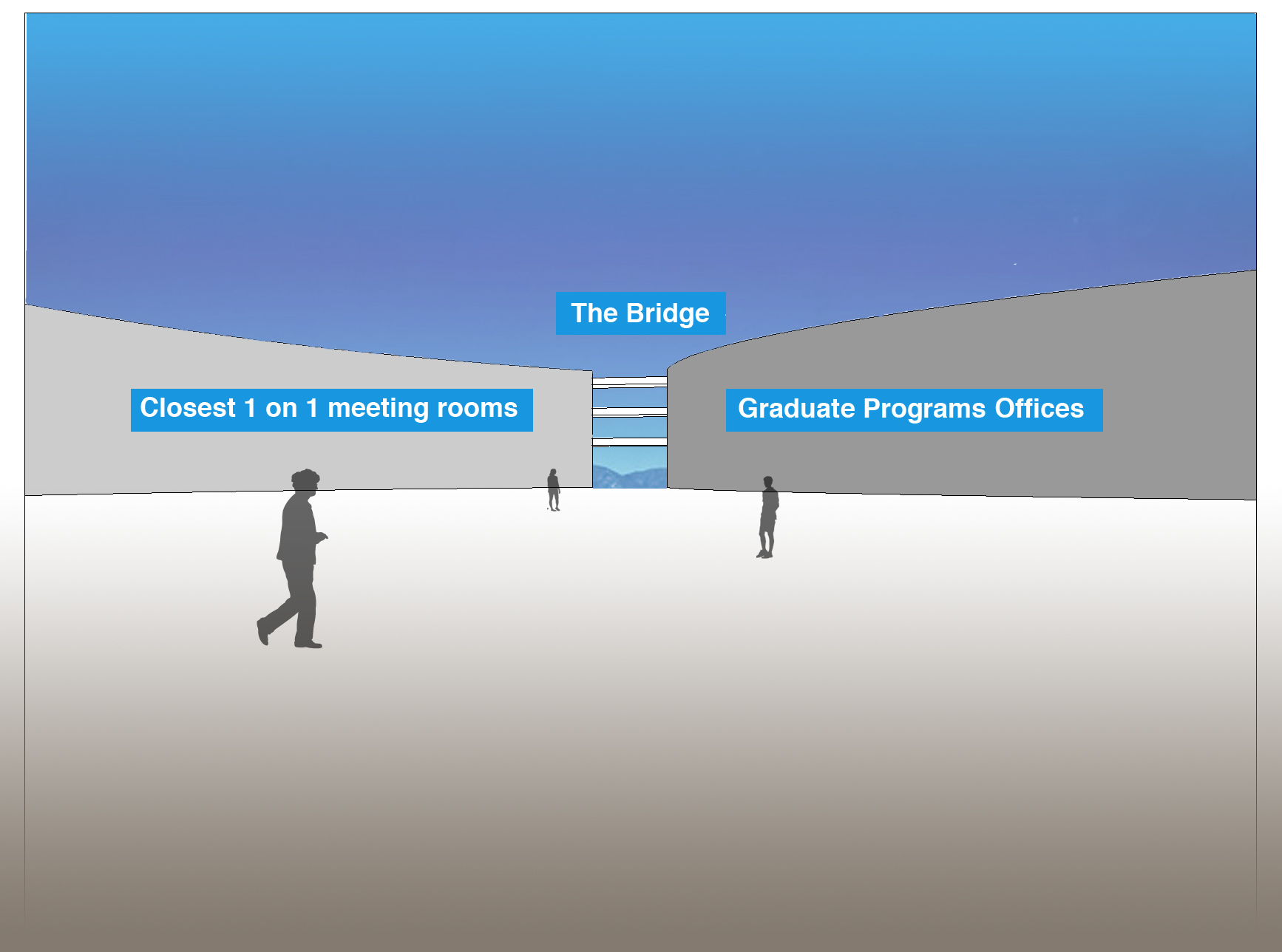

The Graduate Programs office consists of three main teams: recruiting, student services, and career counselors. Its new spaces had everyone sitting in the same small hexagonal mid-height wall cubicle in a large open floor plate. The closest area where one-on-one meetings could be held required a walk across a bridge into the adjacent wing (Figure 1-5).

The recruiting team, who were outgoing and social with lots of collaboration activities, needed a space that was more open. They were constantly taking over the adjacent conference room, turning it into an ad hoc war room for various campaigns. It worked for them but meant that the room was not always available for others.

Student services staff was happy with the setup, as they could focus on their work, but it was awkward to have to walk so far for a one-on-one private conversation. Those challenges were fairly simple to solve by rearranging the space for more open collaborative work and the planned addition of a few small meeting spaces, which would easily allow one-on-one conversations without crossing the bridge to the other wing.

However, the group that really suffered in the new environment was the career counseling team. After less than six months, the team began suffering an alarming rate of attrition. Much of its work was in advising students, and because ASU’s MBA student population has a large international component, these students are far from their usual personal support network. That meant that much of that advising from the career counseling came in the form of personal emotional support. A student might come to a career counselor because their spouse was on the other side of the globe and wanted a divorce. The student needed to make a decision about staying in school. So, that student would sit, half in a cube and half in an aisle, sobbing while the career counselor tried to book an available room. Then, together, the student and counselor would walk across the bridge to the other wing, and finally find a space appropriate for that conversation.

We looked at the career counseling team’s working patterns and realized that if we put them into small offices, grouped together, with a common workroom, they would have the best of the private space they needed with clients (the students), as well as a collaborative area that would support innovation of the services they provided and social cohesion. Luckily, this state-of-the-art building had been designed with 50 team rooms. We identified a small group of these rooms adjacent to the career center, changed out their doors from sliders to locking, and the team was set. The head of that group sought me out about six months later to thank me, sharing that she had filled the remaining positions and was now able to retain, motivate, and build the team she needed.

Understanding Sustainable Engagement

In the example we just looked at, the career counseling group was not enabled to perform their job, a critical factor according to the Towers Watson research. In fact, the physical environment dis-enabled them. Employees left their jobs at an alarming rate until the physical environment problem was fixed. However, enablement also extends to creating the right culture through team structure, motivators, programs, and both the right digital and physical tools. The environment in all aspects must enable high-performing employees to do their best work or they will leave.

According to the research, the other factor for sustainable engagement, being energized, is generated by promoting broad well-being, including encouraging health, management of stress, and providing social supports in the work environment. Understanding these drivers can often allow you to make small/inexpensive corrections, which provide resources that create a sense of well-being.

Let’s consider a study of behavioral strategy applied to creating an environment targeted to well-being in the extreme environment of a prison. Jay Farbstein and Melissa Farling had a hypothesis that being able to see nature would lower stress for inmates and staff (see Figure 1-6). They designed a study to prove this at the Sonoma County Jail in Santa Rosa, CA. Their experiment with design in the prison started with posting large-scale images of nature to the inmate intake booking areas. Officers working in those areas are highly stressed because inmates sometimes arrive at jail in a drugged or emotionally explosive state. The study measured officer stress before and after their shift by using a perceived stress survey, backward digit scan (short-term memory test), heart rate, and incident report (the number of inmate behavior issues). The study took multiple measurements of all 12 officers before and after the landscape mural was installed and also compared average numbers of incident reports in an extended time frame before and after the murals were installed. The results were clear across all methods of measurement. Changing the physical environment by simply installing images of nature had a significant impact on stress levels for both inmates and officers. Reducing employee stress might be as simple as beginning with placing those rooms that have high-stress activities adjacent to windows, installing images of natural landscape, or providing outdoor break areas.

Case Study: PCA SKIN, Not Just a Remodel

PCA SKIN is the industry leader in innovative skin care, with products that bridge the gap between beauty and medicine. The company’s products are only sold to those who have been trained how to use them, preventing poor results through incorrect application. This limitation means that PCA SKIN’s revenue stream comes from (a) selling training to new customers, and (b) selling additional training and products to existing customers. The company has an outbound call staff to sell training and inbound call staff to respond to product questions. Both of these groups interact with a wide range of professionals, from aestheticians to dermatologists. This range of client type means PCA SKIN needs salespeople with different types of knowledge, levels of education, and specific area knowledge that is not necessarily typical of call center workers.

The CEO identified this staffing challenge as critical for business growth, so he replaced many of the call staff with industry professionals. The new staff had worked in the industries that were being targeted and could respond to PCA SKIN product questions, as well as put product questions or training in context to that specific industry. This was a great idea, but many of the new hires saw the call center position as temporary while they looked for their next “real” job, creating employee churn and the major challenge to business growth.

As the salesforce became more professional and developed relationships with clients, the clients wanted to visit the headquarters of the company that generated such great products. However, PCA SKIN’s existing facility was a dated warren of cubicles and the visual brand of the physical space in no way supported the company’s marketing and growth efforts. PCA SKIN needed a headquarters that fit the brand it was selling. My company was initially retained to design its new space, creating a physical brand that would visually support the company brand.

My team went through a discovery phase, and interviewed a variety of stakeholders who would help us understand all of the business issues. Through this discovery, we stumbled on the real problem: hiring and retention issues. With support from the CEO, their leadership team worked with our team to create an environment that reorganized the structure of the company in a variety of ways.

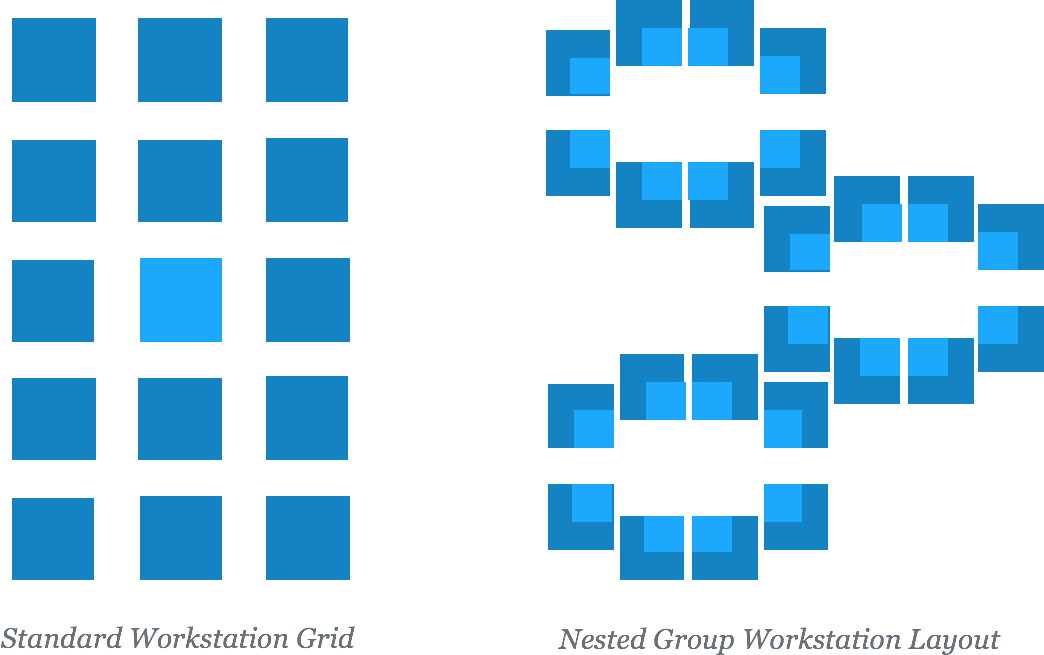

Anthropological research from the last 50 years clearly shows that a sense of individual ownership of results diminishes with increasing group sizes of more than eight people. Jeff Bezos, CEO of Amazon, calls this the “two pizza rule.” Rows of cubicles give the visual and functional message that the cubicle occupant is alone in an ever-expanding hive. As the number of cubicles increase, the individual occupant loses her sense of belonging and feels less responsibility for the outcome of activities taken on by the group. Our goal was to create a connected organization that started with small nonhierarchical groups that were fully responsible for their results both individually and as a small team. We could increase their loyalty (and retention) through team size and a sense of accomplishment. We also knew that if we could influence the staff to respond as a group, rather than as individuals, we could get them into the habit of collective problem solving and increase each employee’s sense of belonging. We accomplished all of these goals with tremendous results.

The original setup was a typical grid of workstations. We collected them into groups of eight and removed the back and side of each workstation so that an individual could face into the corner for focused work or spin around in her chair and be part of the group. Building this configuration we balanced individual needs with team needs (see Figure 1-7).

To further cement each group bonding, each team took its break at the same time. We then remodeled the breakroom to look more like a café, and less like the typical combination lunchroom/fileroom. To do that, we created a green wall of plants and installed a floor-to-ceiling wall mural of a nature scene (which, as you’ll remember from our discussion of Farbstein and Farling’s study, lowers stress). But a café needs to have nice amenities too, so the renovation included a restaurant-quality water and ice machine (drinking more water also lowers stress and increases productivity), as well as a good coffee machine, healthy snacks, and other supports. This all helped staff feel valued and energized.

The other challenge was that staff hiring was broad to provide deep knowledge in a variety of areas, but the customer phone calls came to each salesperson randomly. Only luck would connect the customer to the appropriate serviceperson. However, through this new physical setup, team members began to understand each other’s skills so that calls could be transferred to the most knowledgeable person in that area. By enhancing the idea that both private and public conversations were possible in the same cubicle, we could encourage on-the-job cross-training between individuals of different backgrounds and experience.

The workstation layout also provided opportunities to design for faster on-the-job training. The bulk of learning for any task happens in one of two ways: through mimicry or through problem solving related to actually doing the task. Accessory learning of facts or capabilities not available for on-the-job learning must be taught in the classroom or online, but the bulk of our workplace learning is on the job. What is important about the PCA SKIN experiment is that the design of the workstation layout supported learning through mimicry and enabled learning through doing. We proposed stations that were open enough that a new employee could hear and see how calls were being handled, immersing them in the culture and appropriate response content and tone for PCA SKIN’s customer base. The same openness allowed others on the team to hear the new employee and provide immediate feedback, thus allowing the new person to learn quickly by doing. The small group dynamic allowed coworkers to feel more comfortable giving feedback and encouragement. The openness and group design at PCA SKIN would not only help with the ramp up on specific product and services knowledge, but also illustrate the proper way to relate to a customer in the brand experience.

Outcome: Thinking about Teams, Space, and Training Lead to Success

I went back to PCA SKIN a couple of years later to see if our efforts paid off. The COO noted that training times had been significantly reduced. They now had a practice of placing a new hire or low-performing staff member between two experienced high-performing staff members, which cut training times by more than 30 percent. It has worked so well that the company now rotates its staff every 90 days to continue to cross-pollinate knowledge, building both individual and collective capacity.

In the five years after the remodel was complete, PCA SKIN increased its employee numbers by 61 percent, clearly solving its attraction/retention problem. With that increased capacity, overall revenues increased more than 78 percent. We could have just designed a beautiful space that responded to the initial request of creating a physical brand, but by identifying the business constraint and using behavioral strategy to address the whole environment, not just physical, we drove significant revenue increase.

I won’t argue that rearranging the cubicles or remodeling the breakroom would have worked by themselves—architecture alone doesn’t solve behavioral challenges—but because the designs of all of the systems, including physical space, supported the behaviors that were needed, PCA SKIN was wildly successful. The environment that was created influenced the behaviors that created the culture that delivered the business results.

Conclusion

We know this to be true:

-

Physical space affects the experiences people have in that space

-

Experience encourages or discourages specific human behavior

-

Behavior is responsible for execution

-

Execution is the key to accomplishing strategic objectives

In other words, we know and the data proves that the physical spaces that your team occupies can be leveraged to help you get your business where you want it to go. In today’s world, digital space is an extension of physical space and organization and culture are parts of a continuous work environment. A whole environment behavioral strategy that aligns the physical and digital spaces, organizational structure, programs and amenities, and the right technology can support, encourage, and drive the right behavior patterns, making a significant difference in the amount of effort required to achieve your objectives.

While humans are the biggest driver of growth, differentiated products, and profitability, the biggest impact on human behavior is their environment.

1“The Role of Classification Skill in Moderating Environmental Influences on Children’s Gender Stereotyping: A Study of the Functional Use of Gender in the Classroom,” 1995, http://www.jstor.org/stable/1131799.

2 “The 2014 Global Workforce Study Driving Engagement Through a Consumer-Like Experience,” https://www.towerswatson.com/en-US/Insights/IC-Types/Survey-Research-Results/2014/08/the-2014-global-workforce-study.

3Susan J. Ashford, Cynthia Lee, and Philip Bobko, “Content, Causes and Consequences of Job Insecurity,” Academy of Management Journal 32:4 (1989): 803–829.