Understanding the Chief Data Officer

How Leading Businesses Are Transforming Themselves with Data

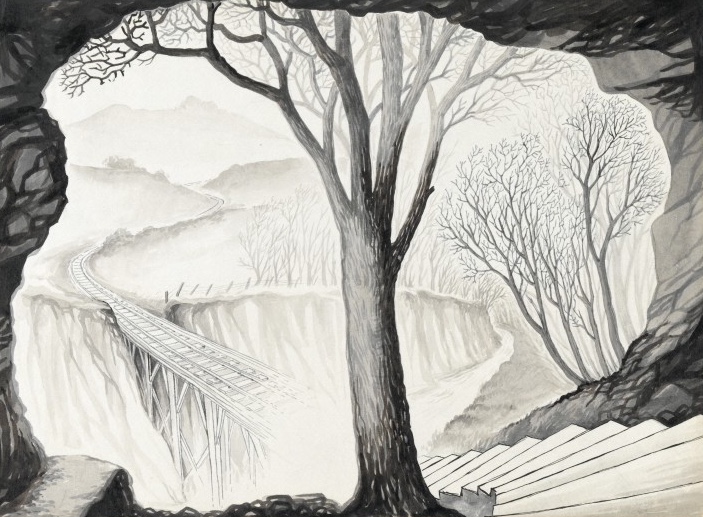

Dreams of a patient in Jungian analysis (source: Wellcome Library)

Dreams of a patient in Jungian analysis (source: Wellcome Library)

Understanding the Chief Data Officer

Introduction

It’s been hard to miss the swelling tide of “big data” over recent years, but just what that term means to business and how it should be managed within an organization is still evolving. With the increasingly vital role technology has come to play over the last several decades, the Chief Technology Officer (CTO) and Chief Information Officer (CIO) were introduced and became familiar roles in many organizations. Less well understood is the nascent but rapidly spreading Chief Data Officer (CDO) position.

Many companies understand that data, when used correctly, can yield tremendous value—or even change entire industries. Just look at what Amazon or Netflix has done with recommendations, to take a “new school” web example, or what Walmart has done with supply chain optimization, to take an “old school” retail example. What company wouldn’t want to achieve such results through data?

If those examples constitute the carrot, then there is also a data stick. Industries such as finance and healthcare, which regularly deal with sensitive personal information, have become more heavily regulated in terms of how they must handle and protect their data. Even without regulation, some recent hacks have made the prospect of a large data breach a very scary possibility for anyone handling credit card transactions.

Whether tempted by the carrot of new products and efficiencies, or harrowed by the stick of privacy and security concerns, many companies have elected to address these issues by appointing a CDO. But the territory is still relatively uncharted.

Right now, there are as many implementations of the role of CDO as there are organizations implementing it. Everything about the job, from reporting structure to primary responsibilities to required skill sets, can vary with the industry, company, and individual. But there are some very distinct patterns and categories, and some common threads that can yield insight for those considering a CDO of their own.

This report presents a picture of the current landscape, as well as some guidelines and best practices for those considering adding a CDO to their own organization. I spoke with a dozen professionals who have performed the role in various settings including healthcare, telecom, finance, marketing, insurance, and government at the municipal, state, and national levels. Their collected wisdom shows how the right data leadership can make companies more customer-focused, competitive, and influential.

The Emergence of the CDO

Perhaps unsurprisingly, some of the earliest CDOs were minted to oversee compliance in industries whose data is heavily regulated. HIPAA (the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act), Sarbanes-Oxley, and the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act all mandate standards for the protection of patient and consumer data. In addition to formal legislative acts, industry ideals such as the PCI (Payment Card Industry) data security standards have made the specific appointment of a CDO seem sensible.

The protection of sensitive personal data and other facets of data governance are one thing, but the creation of new products and services is another: the increasing volume, variety, and velocity of data available to organizations in every industry has made it a raw material that—when properly used—can add significant business value. So more recently, companies outside of regulated industries have also begun to appoint CDOs, in order to create and carry out data strategy, aimed at mining data as a resource and smelting it into new offerings and increased efficiencies.

“There is a massive amount of information that can be used and analyzed to set the direction of the business—or quite frankly could be turned into a whole new business—and that is really where the Chief Data Officer comes into play,” said Mark Ramsey, CDO at Samsung Telecom America. “What has really changed is that now there are so many external data sources, there are so many nonstructured data sources, there are so many things that can be pulled together to create a much deeper understanding from a data perspective, and that goes well beyond what a Chief Information Officer would focus on.”

The comparison between CDO and CIO (or even CTO) is a natural one to make, given that the CIO is also a relatively new position and in a technological field, and the CDO does often work together with the CIO; the two may even be part of the same direct reporting chain. But it would be a mistake to conflate these positions. Even with a very competent and well established CIO, there are areas of specialty and expertise unique to the ideal CDO. While technology is inevitably involved when working with data, the defining goal of the CDO is not technological, but business-oriented. The ideal CDO exists to drive business value.

The Responsibilities of the CDO

When you ask a group of CDOs about their job responsibilities, you get answers as numerous as the individuals you questioned. However, a few key themes do begin to emerge.

The first overarching theme is that the CDO is a very broad role. Those who fill it must focus on a wide variety of tasks, and be able to consider everyday details as well as the bigger picture. The job is about mapping the particulars of a company’s data needs to its overall business purpose in order to create and drive value—and about working successfully with all divisions across the organization so that everyone is pulling in the same direction.

“You have to do, enable, and govern,” said Charles Thomas, CDO at Wells Fargo. “You do a few big broad things; you enable the technology, tools, skillsets that you provide to the enterprise; and you govern far more.”

At Wells Fargo, Thomas and his team are responsible for overseeing what he calls the “data and analytics value chain,” which encompasses the whole data lifecycle from obtaining data to acting on it. This chain as he describes it includes: gathering data into the data warehouse, ensuring that the proper metadata is available, performing analytics to understand the patterns and relationships in the data, figuring out how to employ those insights in an operational way, and then encouraging the relevant decision-makers to execute on the intelligence. Not every CDO role is so all-encompassing, but many are. If the role stops short of yielding operational execution, then its impact is less than ideal.

The second overarching theme is that the CDO must find and maintain balance: between ideal strategies and practical implementations, between short- and long-term budget concerns, and among competing divisional priorities. To achieve this balance often requires great diplomacy and the ability to collaborate with others while educating them on evolving tools, techniques, and landscapes.

Micheline Casey is CDO of the Federal Reserve Board: “What I am setting up my team to do—and thus educating my senior advisory committee on—is about this balance between strategic needs of the organization with moving things forward in agile ways so we begin to add value early, and helping them understand what agile means.”

Casey’s role was created by the Federal Reserve’s Strategic Framework 2012–2015, which contains a section on data governance. In addition to fulfilling the strategic objectives laid out therein, Casey looks for ways to enhance the data their economists have access to. Most of the data the Federal Reserve system tracks is historical, so Casey is pursuing ways to balance that with external data that may be more real-time or even predictive; for instance, she’s meeting with various web companies to understand how their workforce data can be used to augment existing data from federal agencies like the Bureau of Labor Statistics. She’s also working on setting up a Data Lab to support the process of identifying new data sets, tools, and techniques.

In addition to these high-level themes of breadth and balance are some more specific goals and responsibilities common to many CDOs I spoke with: centralization, evangelization, and facilitation.

Centralization

Enterprise-scale companies may consist of dozens or even hundreds of smaller companies, divisions, and other components. And each of these produces data. The CDO is in charge of gathering the data from across these different silos and bringing it into one central place—and into some set of standardized formats—so that it can be analyzed and put to use.

Azarias Reda is CDO of the Republican National Committee (RNC), which does fundraising and marketing as well as voter profiling to help with party elections in many different districts, states, and constituencies. They also run a website, gop.com, which appeals to would-be voters with everything from leadership surveys and discussion of the Keystone Pipeline to brightly colored socks bearing the signature of former President George H.W. Bush. The site is a place to both gather and distribute data-driven research.

“A lot of our work, actually, has to do with collecting this data for all the states and going through a process to make it uniform and nationally accessible,” said Reda. “One of the first areas that emerged for us was creating a unified center for collecting our data from multiple sources within the organization itself, so that we could build a better picture of who the voter is.”

However, whether you’re talking about voters, patients, or customers, internal data is almost never enough by itself. So in addition to gathering the company’s own data, the CDO is typically also gathering external data from open APIs, vendors, or other sources, and making it all work together to answer the questions that matter to the business.

The goal these days is often to establish a “360 view” of who each person is. The argument is that aggregation is not only good for the business, enabling more holistic use of data, but it is also good for the customer. Anyone who has used a customer loyalty card and come to expect personalized coupons or the occasional free cup of coffee just the way they like it has experienced this 360 customer view—and the data required to achieve it—in action.

“No matter who you deal with, whether it is a retailer, or whether it is a financial institution, we have all become trained (and rightly so) to expect to be treated as a person and not a series of products,” said Floyd Yager, CDO at Allstate. In addition to overseeing core data quality and management issues for the auto and homeowners business on the personal line side of Allstate (which constitutes about 85% of their revenue), his role involves thinking ahead about what the company should be doing with data over a three-year horizon. And achieving the holistic customer view is at the top of his list.

The problem is that, since this kind of approach is relatively new, the process of aggregating data requires a lot of work. Most companies are not just set up, but also optimized to look at each each product, service, or group with its attendant data in its own silo.

“We have very good data, but it is organized to help us run our business the way we have run our business for 80-some years,” said Yager. “I need to take all of the data that was very transactionally efficient to help process an auto insurance policy, and join it to all of my homeowners data, all of my life insurance data, all of my commercial insurance data, and everything else I have, so that when Joe Smith calls me, I can look at Joe Smith as that unit, rather than Joe Smith’s auto policy.”

Of course, it takes a lot of time, money, and people power to overhaul legacy systems, and to integrate data from so many different internal and external sources. And integration or aggregation are much better terms than centralization when talking about the data, as very often the pre-existing data-generating systems are left intact. But the theme at work here in the role of the CDO is bigger than just aggregating data: it is also about centralizing the way company priorities are determined when it comes to data-driven projects.

“If you do it the right way and you take an enterprise view, how you build the data and how you do the project can make it easier for the next project to be done,” said Yager, “even if it is in a different area of responsibility. Prioritization actually becomes integration, and not just completing that one task, but how you complete it to make the enterprise work more smoothly.”

Evangelization

The CDO’s team is not a new department that is simply appended onto the old way of doing things, like a third arm that adds incremental capability. It is more like developing a nerve system: it works with all the other parts of the organism, collecting information and passing signals back and forth in a way that allows for better collective action and decision-making. A nervous system is not made of muscle; its job is to inform, not act all by itself.

The CDO team is typically quite small compared to the rest of the enterprise, so convincing others in the organization that this kind of work is worth investing in is critical to success. The CDO must be an advocate for data-driven approaches, and achieve buy-in from colleagues on many levels. This requires a certain amount of visibility.

Rob Alderfer was CDO of the Wireless Telecommunications Bureau at the FCC (Federal Communications Commission) from 2010–2012. “The role of CDO is enhanced by close alignment with the goals of the agency or the organization, generally. So rather than being seen as the data geek who is off doing his own thing, if you are seen as using data as an integral piece of a larger common goal, that is what really gets people’s attention,” said Alderfer.

In order to be an effective ambassador, you also have to be able to speak the same language as the person you are trying to win over to your cause. The ideal CDO is fluent in both business and technical matters—but more importantly, can translate between the two.

Scott Kaylie was CDO at QuestPoint from 2012–2014, and believes the language barrier is more than metaphorical. “Even if a DBA [database administrator] and marketing professional are using the same words, they could have very different meanings,” said Kaylie. For example, he said, when talking about a group of website or application users, a word as simple as all can have two different meanings: to a marketing professional, it may mean “every single user that exists,” but to a DBA, it may mean “every user except these excluded ones, who are in the middle of testing.”

The key to success for a CDO, who must work with stakeholders from all parts of the company, is “being able to speak both of those languages, to understand the business concepts that will drive the profitability of the business, and being able to talk intelligently with the technology teams,” said Kaylie.

Facilitation

Of course, once you’ve won everyone over to the importance of working with data in new ways, you then have to remove some barriers and free up the resources to make it feasible. The ideal CDO is one who makes better, more efficient action possible for the rest of the organization.

“Part of the job was to represent the resource needs for data practices within the priorities of the agency,” said former FCC Wireless Telecommunications Bureau CDO Rob Alderfer. “A lot of the stuff I am talking about, though, is not necessarily money: it is just people’s time.”

Alderfer’s work focused on using data to both encourage public participation in the policy process and improve policy outcomes. From regularly publishing data via an API to releasing the data from an internal report in an accompanying spreadsheet file, he said, institutionalizing open data practices within the agency adds extra work for everyone involved, not just those on the CDO’s own team. So part of his job was to make that as easy and obvious as possible. But, he added, “The fact that the FCC had a Chief Data Officer represents a commitment of resources in and of itself.”

Joy Bonaguro, CDO of San Francisco City and County, also discussed the commitment required from all involved. She regularly convenes analysts and stakeholders from the whole municipality to identify and discuss their challenges in implementing open data and with working internally with sensitive constituent data. San Francisco maintains a website, DataSF, that acts as a clearinghouse for public data, including data about transportation, public safety, health and social services, housing, energy, and many other widely varying topics. “Because it’s a new role and there were all these existing things going on, my strategy with resourcing has been to emphasize the coordination instead of trying to have a bunch of stuff under me,” she said.

Another critical part of facilitating action is providing new tools and lowering the bar to the kind of tasks you’re asking others to do. “The city has a lot of great work that’s happening. Learning about that made me realize that I need to enable this work to continue to happen,” said Bonaguro. “I think I initially came in thinking, ‘Maybe we need to provide analytical services to departments.’ What we found is that it’s better in a lot of ways to have those within the departments.” Her team focuses on providing support to the city’s departments by developing toolkits and offering training.

Yet another method of facilitation, especially within government, is contributing to policy. “The FCC budget is about $450 million a year, but it regulates an industry that is in the hundreds of billions in terms of economic impact,” said Alderfer. “So if you can have an impression on the broader economic impact from a policy perspective, then that’s really where it probably makes sense to focus most of your time. I actually spent a lot of my time at the FCC figuring out how to improve the data that was used in policy decisions.”

Reporting Structures

The responsibilities outlined here are the central themes that have emerged over a period of time. The reality is that, for many early CDOs, job responsibility number one was to figure out where they fit and what their other duties should be. The role has sometimes been created without a very specific idea of what the organization hopes to accomplish with data, or how the CDO role should be positioned relative to the existing hierarchy.

Bonaguro experienced this in San Francisco, where the position was mandated by legislation but not well outlined: “Defining and understanding where the role sits in the existing structure was something that had to be done.”

Micheline Casey also encountered this at the Federal Reserve Board: “They’d never seen a CDO, and they weren’t sure at all what a CDO was supposed to do. They were sure something was needed, but they weren’t sure what that looked like, smelled like, tasted like.”

So what you find right now is that the reporting structures vary every bit as much as the job responsibilities: some CDOs report directly to the Chief Executive Officer (CEO), while others report to the CTO, CIO, or even the Chief Financial Officer (CFO). Some larger enterprises such as AIG have multiple CDOs, one for each major group, and sometimes also one for the overall conglomerate.

“One of the reasons we are seeing such a variability with CDOs is because you may have one business whose definition is that the CDO is really the data steward, and they report to a team within the CIO’s office (so there may be one or two levels down from the CIO). On the other end of the spectrum, we have a Chief Data Officer who is peer to the Chief Marketing Officer and the Chief Financial Officer, and who is really changing the direction of where the organization is going around data and analytics,” said Mark Ramsey of Samsung.

This latter scenario seems to be the ideal one. In most cases, it doesn’t make sense for the CDO to be nested under the CIO in the long run: their areas of responsibility certainly converge occasionally, but the CDO is responsible for organization-wide policy and data management. To go back to the earlier analogy of the nervous system: such a system works best when it is wired directly into the brain of the place.

Challenges of the Role

When your role is nascent and evolving, there are many inherent challenges, to be sure. But add that lack of stability and established expectations to a role that must keep up with a rapidly shifting technological landscape while simultaneously navigating the politics of many divisions and departments, and you’ve got one very tall order.

As described earlier, one of the common responsibilities of the CDO is to gather data from many different sources—internal and external—and integrate it in ways that allow it to be analyzed and put to use. Jennifer Ippoliti, CDO at Raymond James Financial, sees this as one of the significant challenges of the role.

“The biggest challenge is how to deliver on these grand visions that people have of what you can do with data management,” she said, “when your actual data is still sitting in silos, and not consistent, and not using standard definitions, and standard field formats, and so on.”

The technology side of things offers many real challenges. Ultimately, the biggest challenges may be about avoiding technological distractions—staying focused on the business goals—and then getting others to buy in. As we often say in Silicon Valley: the hardest part of technology is not technology, it’s people.

Business Challenges

The most important part of the CDO’s job is to align technology with business goals. Much can be done with data, as the press delight in showing us every day, but the key is to do things with data that will directly support business objectives. The CDO is in charge, in large part, of making sure that the paths an organization pursues with data are pursued for the right reasons. And typically, those are business reasons.

“Data, while supported by technology, is not fundamentally a technology problem. Your information systems can house the data, but your questions—like, ‘Should we be running this program?’—those are business questions,” said Joy Bonaguro of San Francisco. “And technology can help you manage them, but if you don’t have good business questions it doesn’t matter what kind of technology you have.”

Eugene Kolker, CDO at Seattle Children’s Hospital, agrees: “We’re trying to improve business, we’re trying to bring better service to our customers. It’s better to start from that angle than to start from the technology. And in our case, our customers are families with sick children, which makes it all the more imperative that we give our absolute best!”

On data strategy

In order to develop good business questions and to answer them, one needs to have a data strategy. The ideal data strategy is written in collaboration with all the business stakeholders, so it is well understood and agreed upon. It outlines the things that matter to the company, lays out a roadmap for how data will be used to help to achieve those goals, and provides actionable plans for how to get started.

That last part, action, is critical. Without the ability to act, a data strategy is just another document that will moulder away. “It is great to have a strategy, but we actually have to deliver results, and we have to make a difference for the business,” said Floyd Yager of Allstate.

Kolker, of Seattle Children’s, explained that in the healthcare business especially, the ability to take action is imperative. “One of the lessons we learned the hard way is that data analytics, data science, data modeling is not enough. It’s necessary, but we wanted not just to get data and do analytics on it but to get something that is actionable—actionable insights. We wanted to change the business, and change is very tough, especially in an industry like ours where we’re talking about people’s lives and health. It’s not like somebody’s trying to optimize clicks.”

In addition to being actionable, a good data strategy must also be flexible. It should be a living document that can adjust as business priorities change and technology evolves. It can lay out a new roadmap when data indicates that your current tactics are no longer working: when your investment strategy stops yielding a competitive advantage or your supply chain is no longer optimal, for instance, or when another concern altogether eclipses those issues. The kinds of business questions that matter may shift, and questions that used to be very difficult to answer may suddenly become low-hanging fruit thanks to a new tool or technique. There is also the problem that questions tend to breed other questions.

“Invariably, as you answer one question with a particular piece of analysis, it raises five more. And that tends to go on for a while,” said Scott Kaylie, formerly of QuestPoint. “At some point you hit a kind of inflection point where, for certain areas of data or corporate function, you have exhausted a lot of the questions, but there could continually be different forensic type analyses—there is always the potential for some problem to occur in some part of the business, and ideally you have the flexibility and the capability to use your data to shed light on it, and give you indications of the root cause.”

On data governance

Of course, how the data gets used, particularly in certain settings like hospitals and financial institutions, can be very sensitive. As discussed at the top of this report, part of the initial genesis of the CDO role was the need for regulatory compliance and oversight of what’s called data governance: ensuring that data is handled according to strict standards and guidelines.

In newer businesses such as car-sharing or online dating, there aren’t yet regulations regarding customer privacy—but there probably should be. In the absence of any clear guidelines, companies in these fledgling industries must guess at how to avoid violating their users’ trust. To cross that line is not only disastrous for public relations, but also a potential legal problem. Conscientious data governance is almost more imperative in the absence of regulation, since the boundaries between fair data handling and mistreatment can be much less clear.

While it seems like a no-brainer to address these issues before anything else, not everything can be done all at once. The ability to organize and prioritize is crucial, and a CDO can bring a lot to the table here.

“On the governance and policy side of things,” said Jennifer Ippoliti of Raymond James, “I have created a central point of escalation for data issues so that we can look at them together: we can prioritize them independently in terms of what is best for the enterprise as a whole—and not just one particular user or group of users—and then get that into the technology pipeline so that we can fix things in the order that is best for the firm. That didn’t exist before I came along.”

She elaborated on her process by naming distinct steps. “There are two sides to the governance: One is making the business decisions and prioritizing them. The other is more of a release-planning exercise, where we work with the different applications groups, determine which ones need to be involved, and then slot the changes into their release cycles in a way that is consistent with all of our policies.”

Micheline Casey agrees that working out data governance can be time-consuming. Especially at a place like the Federal Reserve, where every move is scrutinized by powerful banks all over the world, nothing happens without a lot of careful consideration and conversation; the idea of agile iteration is foreign to an organization full of economists who want to be 100% sure of everything before publication.

Put that way, it’s easy to imagine why the CDO would have to have numerous lengthy conversations to put new data policies in place. But the perception is that data governance is almost automatic. “They thought it was like a chia pet where you added water and all these data governance policies just sprouted out of thin air,” said Casey, “but they are realizing it’s a lot of heavy lifting.”

The People Side

This idea of perception as an obstacle is a very significant one. According to Eugene Kolker of Seattle Children’s Hospital, it’s the most significant one. “The main challenge is not technical, it’s not on the analytics side, it’s not even to get some data from multiple systems (which is extremely complicated in our case),” said Kolker. “It’s about people.”

During the first years he served as CDO, in fact, Kolker noticed that similar programs his team was running inside the hospital were yielding very different outcomes. “We were thinking, ‘They’re the same, why is one working and one not?’ It was the most crucial angle of people.”

So now, his team takes a more active approach to the human part of the equation. “We’re not just focusing on specific tasks, projects, but on specific people who can make decisions and act on them,” he said. “We engage people like we are internal consultants, and utilize the best practices in consulting approaches and business processes.”

Charles Thomas of Wells Fargo also sees data evangelism and reaching out to others in the organization as the biggest challenge of the role. “That’s been the majority of my time: not convincing them that they should use data, but convincing them that they should use it in a holistic fashion,” he said.

The key to successful persuasion, Thomas added, lies in showing people how they can be even more successful than they currently are. “When you’re in a company that has done really well, it’s showing people the art of the possible. There aren’t a lot of things that are broken here. There aren’t a lot of things that we’re not doing well. The question is, are we optimizing or doing as well as we possibly could?”

It’s also about pulling focus away from the individual agency or division, and back onto the company as a whole: centralization is about more than just data—it’s about working for the greater success of the company and pulling in the same direction.

“My job is to help them see the power of their vertical through the lens of the horizontal. In other words, helping them see that playing enterprise ball has direct benefit to them,” said Thomas. “The subagencies have all grown up with a certain way of doing data and analytics. It’s about, not telling them their approach has been wrong, but their approach is suboptimized for an enterprise view.”

The phrase that Thomas used, “the art of the possible,” is one that came up several times in the course of my various conversations. Prince Otto Eduard Leopold von Bismarck, Duke of Lauenburg, was Prime Minister of Prussia in 1867 when he famously said during an interview, “Politics is the art of the possible.” So perhaps what so many CDOs are inadvertently saying is that their job is all about politics—and they wouldn’t be wrong. As Otto von Bismarck would go on to oversee the (first) unification of Germany into a single nation, and a good part of the role of CDO is about unifying the various business units into a single data-driven organization, the reference seems particularly apt.

The good news is that, while persuasion may still be necessary regarding the finer points of process or possibility, the overall importance of data is becoming more and more apparent. “Day-to-day it seems to get easier,” said Floyd Yager of Allstate. “I like to think some of that is my great influence walking around and talking to people and getting them to see. But I think, quite honestly, a lot of it is that you can’t pick up a magazine anymore without there being an article about big data or analytics and how it is changing the world.”

Deciding to Hire a CDO

If all of this has made you think that your own company could benefit from having a CDO, then here are some important things to consider before you proceed.

Know Why You Want One

As we’ve seen, the responsibilities and reporting structures attending the CDO role can vary quite a bit. To avoid wasting time or, worse, hiring the wrong person for the job, it’s best to take some time to outline the particular needs your organization has around data.

Some questions you should ask of your key business stakeholders include:

- Are you part of a regulated industry or are there professional data standards that will make compliance and data governance your highest priority?

- Do you need to reorganize your data and your focus from being product-centric to customer-centric?

- Are you missing opportunities to add products or services to your offerings, which could be illuminated by internal or external data?

- Could your current processes and outcomes be optimized even further by better analytics?

- Are there data-derived insights in one part of your organization that could benefit other divisions if those insights were shared?

Once you’ve identified your primary reason for hiring a CDO, then it’s time to start thinking about the possible rewards of having one, and building a set of use cases that will get others excited about these possibilities.

“You have to generate demand for the role before you hire somebody and get them to do the work,” said Charles Thomas of Wells Fargo. “People need to believe that we really do need to look at the customer end-to-end. If you don’t do that, the CDO spends their first year or two justifying why they’re there.”

Develop a list of use cases where the ability to share data and insights could improve the way you do business—and the way other stakeholders could perform in their own roles. Then the CDO you put in place won’t have to spend quite as much time on overall evangelism, and will be able to hit the ground running on issues of data strategy and governance when they arrive.

Look for the Right Skill Set

Today’s CDOs come from different backgrounds: some were engineers who had the business mindset required to move into the role, and others were business people who had a keen awareness of technology and the soft skills to work with other technologists to get the job done. Which set of skills should be deeper depends in part upon what you need the CDO to accomplish.

“I really think data engineering is what defines this role,” said Azarias Reda of the RNC, when you are “building products that depend on or that benefit from the data that you have collected.” But if you’re looking to answer important questions about your competitive landscape, then you may need someone with a deep industry expertise who can help ensure that you’re formulating the right questions.

Whatever your needs or your goals, every CDO will rely not only on their own background and experience but also the skills and experience of stakeholders across the company. So every CDO needs to be able to speak knowledgeably about both technology and business.

“Being able to bridge the language of business and the language of data and technology, and being able to translate between those two, is the critical skill set,” said Scott Kaylie, formerly of QuestPoint. “And I think typically that’s going to be someone who is really strong in one, and then can understand the other.” Not only the ability to understand the other, but also the innate curiosity that drives someone to ask questions and to learn, will be a significant asset.

Finally, while the ability to work well with others is a “nice to have” characteristic for any employee, the importance of diplomacy to the role of the CDO can’t be overstated.

“So much of being a CDO is prioritizing decision-making and getting decisions made by an organization,” Jennifer Ippoliti of Raymond James explained. “The CDO often is a person who ends up having to say ‘no’ to a lot of people: ‘No, we can’t address your issue until next year or the year after.’ And that needs to be done in a way that is not going to make a lot of enemies.”

Micheline Casey of the Federal Reserve Board agrees. “Whether you’re talking about the business side of the house or the tech side of the house, the CDO is balancing a lot of often conflicting priorities and needs across the organization,” she said, “so the ability to communicate well to everyone, from senior business executives down to the technical staff on a day-to-day basis, is another really important aspect of this role.”

The ideal candidate has a mix of technical chops and business savvy, with the political skills to work well with others in all parts of the organization. If this sounds a little bit like a unicorn to you, well, you’re not far off.

The Availability Gap

To find a hiring prospect with an equal mix of technical, business, and people skills is a tall enough order. To find a prospect who also has all of that plus the requisite experience to work at the executive level is very difficult indeed.

“In my mind, a true CDO is a seasoned executive that has built up very deep knowledge of data and how to apply that data. And that is something that takes 15 to 20 years,” said Mark Ramsey of Samsung. “It is very similar to if you are looking at a Chief Financial Officer for an organization. A true CDO is going to have that level of acumen from a data and an analytics perspective.”

While many universities are now adding business classes to their data programs—and vice versa—today’s graduates won’t be ready for executive hiring until long after tomorrow. According to Russell Reynolds Associates, “The spike in demand for Chief Digital Officers has been felt globally. In Europe, the number of search requests for this role has risen by almost a third in the last 24 months. The United States has seen the same growth in half that time.” So we’re facing an inevitable gap during which companies must be even more diligent about preparing properly for the hiring process: mapping out their priorities and goals and understanding which skills need to run deep and which can be learned on the job or acquired through collaboration.

Of course, there are some things you can do to make your company and the role of CDO within it as appealing as possible to qualified candidates. The first and most important is to know why you want one, as explained earlier: to understand what your goal is in hiring a CDO, and to be committed to that goal.

“The exciting thing for CDOs, and what’s going to attract the ideal CDO, is a situation where there is a real opportunity to transform the business,” said Ramsey. “Where the company is really serious, they are committed, and they are looking for ways to really transform, those will be the ones that will attract the top-performing CDOs—as opposed to sort of, ‘Hey, everybody is getting a CDO and we probably need to have one, too, and we’ll get some incremental benefit out of it.’”

The most successful CDOs are the ones who have the business acumen to understand what needs to happen in order to support business objectives; the technology skills to select the right tools and techniques to make it happen; and the diplomacy to get the buy-in needed to get everyone else pulling in the same direction. When that happens, the only possible outcome is tremendous change. But even change for the better—Progress, as it’s often called—is by nature disruptive. So you’d better be ready for it.

If you are, and you can demonstrate that to the right candidate, then your company could wind up on par with the Amazons and Googles of the world, using data to disrupt entire industries. And shape the future.

Conclusion

Just as the duties and purview of the CIO used to vary from company to company, so are the duties and the purview of the CDO a bit muddy right now. Over time, it may stabilize as the CIO role did: possibly even into multiple distinct positions. But the common threads of centralization, evangelization, and facilitation are likely to remain. In addition, the two distinct realms currently covered by CDOs, data strategy and data governance, will only become more important.

Data strategy—meaning the way data is used to generate new value—is important to any business’s ability to remain competitive in its marketplace, but perhaps most so in those industries where new products and approaches can potentially disrupt traditional ways of doing things.

Data governance—meaning the way data is gathered, stored, and protected—is critical to every organization, but perhaps most so in those industries where sensitive personal information is collected and regulated. There, a CDO has often been appointed in order to oversee compliance efforts.

Finally, a holistic view of the customer—not just how they interact with one product or service, but a 360-degree view of who they are and what they care about—is the approach that we as consumers are being trained to expect from the institutions we interact with. Whether you’re trying to understand who they are likely to vote for, or what insurance policy they’ll need, or how many strawberry toaster pastries they’re likely to buy when a hurricane comes to town, the goal is to combine data you already have about them internally with other useful external data to get the big picture of who that person is so you can anticipate their needs and preferences.

Whatever you do, whether you’re currently in the role of CDO or looking to create or to fill that role within your organization, be sure you’re doing it in such a way that it will create value for your business. That’s the entire purpose of working with data, and it’s the primary role of the CDO in a nutshell.

“If we’re not measuring and gleaning value from what we’re doing,” said Charles Thomas of Wells Fargo, “this will be a passing fad. And it will be a huge missed opportunity, because data will only become even more important in our organizations.”