Becoming an accidental architect

How software architects can balance technical proficiencies with an appropriate mastery of communication.

Railway Station (source: herbert2512)

Railway Station (source: herbert2512)

One of the demographics Brian Foster and I noticed in the several O’Reilly Software Architecture Conferences we’ve hosted is the accidental architect: someone who makes architecture-level decisions on projects without a formal architect title. Over time, we’re building more material into the conference program to accommodate this common role.

But how does one transition from developer to accidental architect? It doesn’t happen overnight.

As a developer, it is easy to get excited about new stuff: tools, frameworks, approaches, and so on. Most developers are instant gratification addicts and love to discover new things. When working on a solo project or running a small team, most choices revolve around what’s cool, what haven’t I gotten a chance to try, and many other interesting things. After choosing tools based on a current fad, “best practices,” or a host of other reasons, you realize that the tool you’ve chosen has serious shortcomings that you didn’t anticipate.

The journey from developer to architect

Once you’ve been burned several times on projects by picking what’s cool, you start to look more closely before committing to a tool or framework. Rich Hickey, the creator of Clojure, makes a penetrating observation:

“Developers understand the benefits of everything and the tradeoffs of nothing!”—Rich Hickey

While excitement to play with new tools still exists, it becomes tempered over time by pragmatic tradeoffs. Part of the journey from developer to architect comes from exposure to tools that both work and ones that don’t—only by observing both do you acquire wisdom.

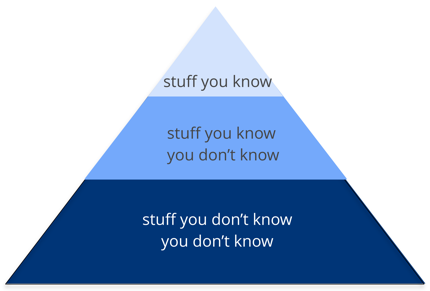

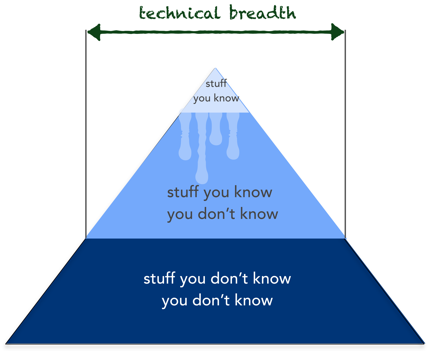

Mark Richards, my co-presenter in the Software Architecture Fundamentals video series, has an interesting observation about architectural knowledge over time. With Mark’s Pyramid, he makes a keen observation about career-long knowledge acquisition, particularly the transition from developer to architect. First, consider this knowledge pyramid, encapsulating all the knowledge on Earth:

Any individual can partition that knowledge into three sections: Things You Know, Things You Know You Don’t Know, and Things You Don’t Know You Don’t Know. A developer’s early career focuses on expanding the top of the pyramid, to build experience and expertise. This is the ideal focus early because you need more perspective, working knowledge, and hands-on experience. Expanding the top incidentally expands the middle section; as you encounter more technologies and related artifacts, it adds to your stock of Things You Know You Don’t Know.

Technical depth and breadth

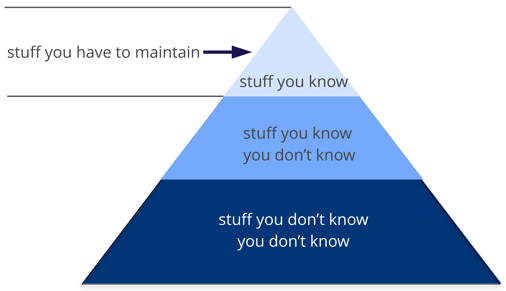

Expanding the top of the pyramid is beneficial because expertise is valued. However, the Things You Know are also the Things You Must Maintain—nothing is static in the software world. If you become an expert in Ruby on Rails, that expertise won’t last if you ignore it for a year. The things at the top of the pyramid require time investment to maintain expertise. Ultimately, the size of the top of your pyramid is your technical depth.

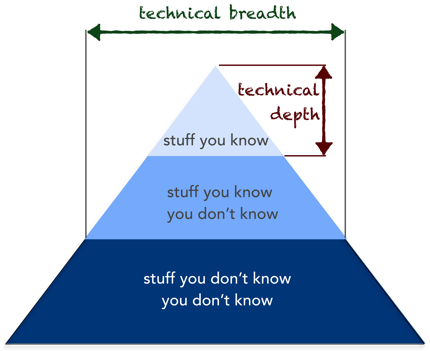

However, the nature of knowledge changes as you start in the architect role. A large part of the value of an architect is a broad understanding of technology and how it can be used to solve particular problems. For example, as an architect, it is more beneficial for me to know that five solutions exist for a particular problem than to be a singular expert in only one. The most important parts of the pyramid for architects are the top and middle sections; how far your middle section penetrates into the bottom section represents your technical breadth.

As an architect, breadth is more important than depth. Because architects must make decisions that match capabilities to technical constraints, a broad understanding of a wide variety of solutions is valuable. Thus, for architects, the wise course of action is to sacrifice some of your hard won expertise and use that time to broaden your portfolio.

Some areas of expertise will remain, probably around particularly enjoyable technology areas (mine is programming languages), while others usefully atrophy.

Mark’s pyramid illustrates how fundamentally different the role of architect compares to developer. Developers spend their whole career honing expertise, and transitioning to the architect role means a shift in that perspective, which many architects find difficult. This in turn leads to two common dysfunctions: first, an architect tries to maintain expertise in a wide variety of areas, succeeding in none of them and working themselves ragged in the process. Second, it manifests as stale expertise—the mistaken sensation that your outdated information is still cutting edge. I see this often in large companies where the developers who founded the company have moved into leadership roles yet still make technology decisions using ancient criteria (I refer to this as the Frozen Caveman Antipattern).

Communication and networking

Most people would probably agree that communication is a key skill of an architect. With that said, very few architects actually apply strategies for successful communication as part of their jobs. Since many of us have technical backgrounds, we tend to revert to our technical strengths when problems come up. As you continue forward on your journey to become an accidental architect, learn how to communicate well with people in your organization using the terminology they use on a daily basis.

The skill to develop is the ability to pick up on the language in a group rapidly and to use it effectively, even within the course of a meeting. This means learning to listen effectively during the course of your time with a group and to start cataloging the terms. By communicating with someone in their natural environment, you can overcome any barriers to trust and increase the possibility for open communication.

One way to start building open communication skills without too much risk involved is by attending local industry meetups or conferences that promote networking as a vital element of the event. Not only will you be able to sharpen your technical chops, but you’ll be able to connect with more experienced colleagues and explore how they cultivated their own communication style over the course of their career. As already mentioned above, careful observation and listening are your best friends here.

Conclusion

As an architect, focus on technical breadth so that you have a larger quiver from which to draw arrows. If you are transitioning roles from developer to architect, realize that you may have to change the way you view knowledge acquisition. Balancing your portfolio of knowledge regarding depth versus breadth is something every developer should consider throughout their career. What’s more, being able to communicate this knowledge in a clear and concise way that’s appropriate for the audience at hand ensures your message is met with conviction and organizational buy-in.

Becoming an accidental architect entails realizing this shift has already started happening. In 2018, both O’Reilly Software Architecture Conferences in New York and London feature sessions specifically designed to help make your architecture—and working relationships—less accidental.