Climbing down from the clouds

From abstract idea to concrete implementation.

Staircase (source: Pixabay)

Staircase (source: Pixabay)

We often underestimate the challenges involved in extracting abstract thoughts from human minds and turning them into working software. The idea in our head seems obvious, until we have to explain it to others. Then the description we offer up to others seems obvious, until we need to visualize its interface. Then the interface seems obvious, until we need to start implementing it. And then it’s turtles all the way down from there.

At each of these steps, there is an order of magnitude leap in the level of specific details you need to consider—but it never feels that way until you spend some time digging into a problem space. It would probably surprise all of us if we could conceptualize the steadily increasing complexity in our projects as we worked our way through the entire software development lifecycle.

In this article, I won’t go quite that far, but what I will do is walk you through the first few steps in building a simple 2D video game. In doing that, it should be pretty clear to see how steep the path is from the cloud down into the weeds, even on the most simple projects.

An idea expressed in words is worth a thousand daydreams

Every new project starts with hopeful wondering about its future potential. Ideas cost nothing to think up, and so there isn’t any friction to prevent you from setting your sights high.

“I am going to build a great new video game! It is going to be a realtime puzzle game, where you have to place workers on a factory floor to run machines and produce various kinds of widgets as quickly as possible.”

As long as your thoughts stay trapped in your mind, there is no need to be specific. You may have hundreds of vague feature ideas stacking up before you even take a look at what might be involved in implementing them.

But the moment you express a project idea to another human being, the process of reification begins. At a minimum, some sort of specific example will be needed to kick off a conversation about your project.

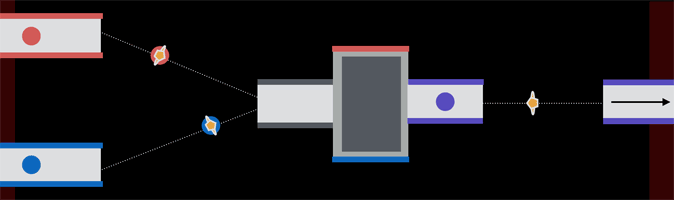

“Imagine a factory floor with two conveyor belts coming in from the left side of the screen… one carrying red widgets and another carrying blue widgets. In the center of the floor, there is a machine that takes red and blue widgets as inputs, and produces purple widgets as outputs. On the right side of the screen, there is another conveyor that is used to ‘ship the widgets’, completing the process. Your goal would be to place robotic workers to move the widgets around and operate the machine.”

If you choose a simplistic example (as above), your idea may come across as trivial and uninteresting. But if you describe a scenario that is even slightly more complicated, your attempt at a verbal explanation will collapse under its own weight. So it’s best to start with most basic possible thing you can think of, and work your way up from there.

A picture is worth a thousand words

Pitching your idea to someone using nothing but your words might lead to some useful questions that will inform your design process, but don’t count on it. The real purpose of getting feedback before you’ve done any work at all is just to force you to express your ideas about your project in a more concrete fashion.

The first useful artifact that may come out of this discovery process is a mockup of some sort, even if it is nothing more than a minimal wireframe:

Immediately, the image makes certain ideas more tangible. The verbal descriptions left the entire visual structure of the game up to the imagination. Although there was the concept of conveyor belts that transported widgets, machines that transformed widgets, and workers that carried widgets between the conveyors and machines, there was no indication of how all of that might work.

The mockup tells us otherwise—but the moment before it was created, the verbal description would have described a grid based board game layout equally well. Now when you combine the image and the text-based explanation, you end up with a very different (and more specific) concept in your head.

From here, new questions start to flow immediately:

The mockup shows workers moving along a path, but what is the UI for defining those paths?

- What are the rules for picking up and dropping widgets?

- Is the game running or paused when workers are being placed?

- Is it possible to change a worker’s path once it has been set?

- How fast does everything move?

- What happens if workers collide with one another?

- What if they collide with machines?

- What if workers put the wrong combination of widgets in a machine?

- Do the conveyors continuously deliver widgets, or do they only send a new one each time a worker picks one up from the drop-off point?

- Do the workers continuously move along their path, or do they stop and wait at their pickup point?

By providing a visual example, the focus of the discussion shifts from abstract design ideas to concrete game mechanics. Now that you know what things look like, you immediately begin thinking about how they move.

A prototype is worth a thousand pictures

All of the questions that have come up so far are potentially interesting to explore. But in order to make any real progress, it’s necessary to focus. By carving out a small vertical slice of functionality, you can begin to experiment with some ideas and see where they take you without getting overwhelmed.

For example, you might do a technical spike where you implement basic worker placement and widget movement. Given three workers and a single widget, you could pass the widget around from worker to worker, as shown in the video below:

Despite its lack of polish, what you see above took several hours to put together. It’s the end result of a dozen micro-scale experiments, some of which ended up being dead ends. The payoff of this demonstration is that it answers several questions that came up from the mockup, even if some aspects of it will inevitably evolve once the game is developed further.

And this is where our real struggle begins…

As you climb down from the clouds, things begin to take a lot more time and effort. An idea in your head is perfect because it is vague, but when you try to execute upon it in reality, you are forced to communicate in increasingly granular terms—first to humans, and then to the computer.

The computer is the most unforgiving communicator of all:

- It tells you that a line is not simply defined by two points and a thickness, but instead must be rotated and translated in a three dimensional space in order to appear (from the viewer’s perspective) to have the thickness you’d expect it to.

- It tells you that even if your other applications on your laptop seem to understand a right click on your trackpad, not all software agrees. Whatever low level game framework you’re using sees that as a left click, so you’ll either need to use a mouse or choose a different UI.

- It tells you that except for a handful of named colors, any other color you might want must be picked by specifying a precise value between 0-255 for each of the red, green, and blue components in that color.

There is such a distance between the thoughts in our head and the code we write that it’s a small miracle that we get anything done at all.

And yet, this is our job: to climb up and down the ladder of abstraction over and over, acting as an interpreter at every rung. It is both the pride and the peril of being a programmer, and it pays to get good at it.

Editor’s note: Gregory is working on a book about the non-code aspects of software development, called Programming Beyond Practices. Follow its progress here.