Clinical trial? There’s an app for that

Several new apps are making it easier for doctors and patients to conduct clinical trials.

Launching an experiment (source: Myfuture.com on Flickr)

Launching an experiment (source: Myfuture.com on Flickr)

When the Cleveland Clinic was looking for participants in its more than 130 cancer trials, its outreach teams didn’t just cold-call doctors and hospitals. They tried something new: they launched an app. The Cancer Trial App is designed for two distinct populations: patients looking for clinical trials and doctors who are treating those patients. Users who download the app either on iOS or Android receive information on trials by disease, phase, physician, and hospital location. In addition, the app details each trial’s objective, eligibility rules, and progress.

The Cleveland Clinic’s app is a simple solution to a complex problem: how to make clinical trials easier for individuals to participate in. Because of a lack of vendors, complex regulatory tools, and institutional inertia, many of the digital workflow and recordkeeping tools that are commonplace in other parts of biology never made it to clinical trials.

According to Premier Research, a life sciences consulting firm, only several hundred of the more than 150,000 mobile health applications published as of December 2016 focus on clinical trials. And of those, most are directory apps like the Cleveland Clinic’s, rather than more complicated apps that enhance the patient experience.

However, innovation is happening in the clinical trial mobile app space—even if it’s taking longer than expected. In the United States, the Food & Drug Administration is working with stakeholders in clinical trials to examine ways smartphone apps can enable speedier, more cost-effective clinical trials that speed up the new drug approval pipeline. The FDA has a public docket out on “Using Technologies and Innovative Methods to Conduct FDA-Regulated Clinical Investigations of Investigational Drugs” that seeks to create consensus.

The Challenges

Designing apps for cancer studies and automating patient data is far more complicated developmentally and legally than creating a new smartphone game, which is why development has been slow.

Stakeholders need to manage the following factors:

- The cost of app development, which is a challenge when many pharmaceutical companies don’t have robust, in-house Android and iOS teams and may not know what questions to ask outside contractors to keep costs down

- Privacy and quality expectations in randomized clinical trial research

- Regulatory issues

- Inside the clinical trial world, a culture that prioritizes written documentation and written paperwork over digital recordkeeping, at least when interacting directly with patients

There are several ways of dealing with these challenges. Additionally, new innovations such as Apple’s ResearchKit and CareKit open source frameworks break down the barriers that prevent researchers, pharma companies, and others from building mobile apps that enhance the patient experience in clinical trials.

In promotional materials aimed at researchers, Apple emphasizes how easy these apps are to use: “Perform(ing) activities using the advanced sensors in iPhone to generate incredibly precise data wherever you are, providing a source of information that’s more objective than ever before.”

Helping Researchers with Trials

The potential of smartphone apps for easing patient experience during the research and trial process has fascinated clinicians.

No 483 For Me! (Figure 1-1) is an iOS app developed by William Tobia, a lead clinical research instructor at GlaxoSmithKline (GSK). It’s designed for clinical research site staff and aims to sharply reduce FDA inspection findings by training them on what to look for, thus enhancing the patient experience.

In an email interview, Tobia said that “compliance with the protocol and FDA regulations is a priority in clinical research but, for some staff, it is difficult to locate the applicable regulations. The purpose of this app is to make it faster and easier to find the information they need on the FDA’s website.”

Once users open the app, they click on an icon corresponding to their area of interest and see the regulations—never having to search on the FDA’s sprawling website for them.

No 483 For Me! also contains information about and quizzes on noncompliance.

Styluses and Tablets

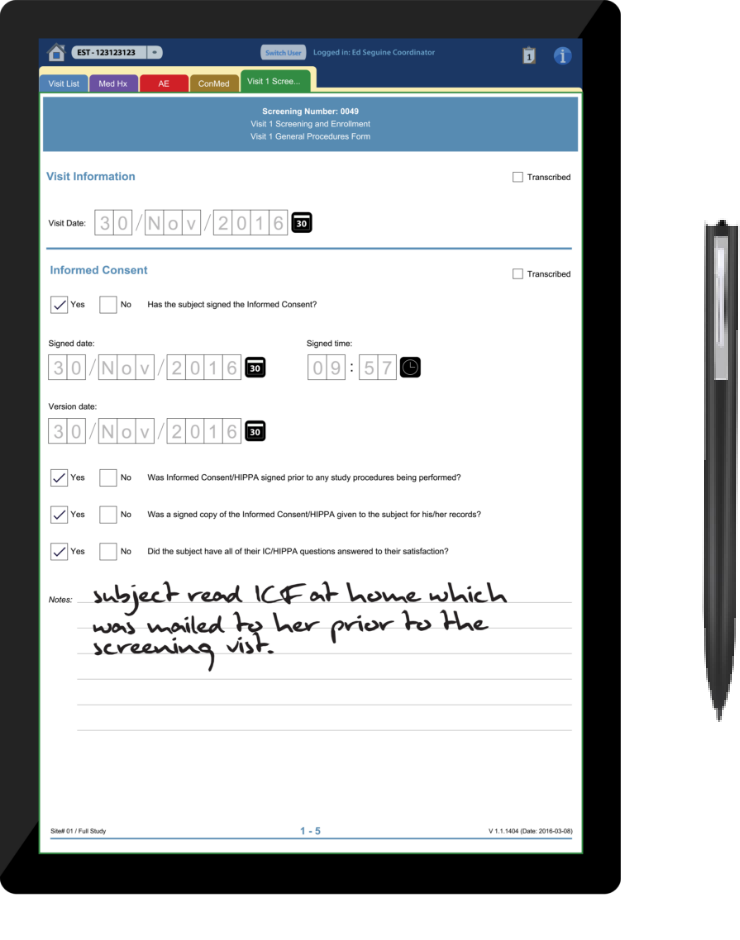

Clinical Ink (Figure 1-2) is a Massachusetts-based company whose product, SureSource, is a tablet-centric software suite designed for entering data via stylus during clinical trials—something the company says provides cleaner data faster and can eliminate paper documents.

“The stylus works with tablet, and is meant to emulate –it’s really for the ability to collect data at site,” says Ron Quinn, Clinical Ink’s vice president of marketing. “It emulates the paper and pen process. You can enable styluses to be touch enabled, to type or use the stylus to make a mark, and it records. Once you ink something, it’s permanent.”

According to one case study published on Clinical Ink’s website, the app also has capabilities for remote monitoring, video uploads, image capture, and push-button randomization.

Clinical Ink’s product strategy ties into a fact of clinical research: clinicians tend to prefer pen and paper and time-tested workflows for data entry rather than new methods, even when they could enhance patient experience. In sales materials, Clinical Ink emphasizes its product sharply cuts down on transcription and data entry time and costs.

Due to factors including regulatory considerations, lack of time to train on new methods, a preference for pen and paper, and cost considerations, tablets and smartphone apps aren’t used on a regular basis in clinical trials. Clinical Ink hopes to change this, and hopes that their product has enough selling points to convince researchers and pharma companies of its worth.

This means overcoming existing worries about using tablets in clinical research. According to a recent white paper published by Clinical Ink, a survey of 517 research coordinators and investigators using the company’s product found that key difficulty points for sponsors and on-site personnel dealing with electronic data capturing (EDC) include transcription time, having to verify transcribed data is correct and completing paper sources, and updating sources and responding to queries. Systems like Clinical Ink are designed to reduce the time and expense involved.

Smartphones and Parkinson’s

One of the most audacious attempts to leverage smartphones for patient-oriented clinical trial innovations comes from mPower. A massive smartphone-based patient study involving more than 9,000 participants, mPower (Figure 1-3) uses an app to monitor and understand the causes of variations in symptoms of Parkinson disease.

What makes the study especially fascinating is how it leverages the sensors inside iPhones and optional wearable device data to collect 24-7 information.

According to a 2016 Science Data report on mPower (Bot et al. 2016), the study takes a highly untraditional approach to recruitment and onboarding. The app itself is the primary recruitment mechanism and uses what lead author Bot calls a “novel remote approach to enrollment” where participants—both those with Parkinsonian conditions and a non-Parkinson’s control group anyone can join—self-guide themselves through the consent process before opting in to join the study. The consent process also includes an explicit decision point requesting if data participants donate to the study can also be used for secondary research purposes.

Sage Bionetworks, the nonprofit biomedical research organization that developed mPower, says that the study lets users track symptoms through fitness tracker and game-like activities, including finger tapping, a memory game, speaking, and walking. In early results, Sage found distinct correlations between intake of medication and participants’ Parkinson symptoms which potentially could help researchers personalize treatment plans and care. New windows of intervention could be developed as well.

The study is one of the first of its kind and includes massive open source data repositories such as a developer portal and a large presence on GitHub.

Science 37 and Smartphone-based Studies

Another approach comes from Science 37 (Figure 1-4), a Los Angeles-based firm whose platform NORA (Network Oriented Research Assistant) is designed for telemedicine participation in clinical trials through smartphones or computers. By using NORA for clinical studies, sponsors are able to reach trial participants who live in rural areas, work during daytime hours, or otherwise could not take part in a conventional trial.

As part of Science 37’s business model, sponsors pay for iPhones, which are then provided to trial participants in order to input data. Kelly Chu, Science 37’s chief technology officer, notes that participants can input info through form entries, text messaging, video chats, or whatever other communication method suits both them and the trial stakeholders.

“People gravitate to video chat, and seeing who is on the other end,” Chu says. “They don’t see us in a brick-and-mortar setting.” He calls messaging as opposed to video chat “lower friction” and adds that it benefits patients when no visual data needs to be given and they may feel uncomfortable on camera. His company sees telemedicine as a way to reduce the traditional withdrawal rate of 30% over a three-year-long clinical study.

Science 37 is well funded. The company raised an initial $31 million in Series A and Series B funding, and raised another $29 million in early 2017. Glynn Capital Management led the latest funding round, and other investors include Amgen Ventures and Sanofi-Genzyme BioVentures. Sanofi has an agreement with the company to look at improving recruitment and reducing trial times.

Noah Craft, Science 37’s cofounder and CEO, describes his company as “one-third tech and two-thirds clinical.” This means creating a platform which steers information to researchers and sponsors as quickly as possible while using behavioral tools to make sure patients stay engaged in trials. As he puts it, “Even though you can ping a patient twice a day to ask if they have taken their medications, people don’t like being pinged twice a day by anybody.”

Into the Future

Smartphone- and tablet-based, patient-facing technologies hold great potential for improving clinical trials and creating a better patient experience. But despite big steps forward like ResearchKit and Patient Kit, changes won’t happen overnight.

Tobia is optimistic—he says mobile health technologies can better engage patients and help them understand clinical research options with healthcare providers and have an easier time participating.

However, Craft notes that there are big regulatory and development factors at play. As he puts it, “Regulations around authenticating and identifying who a patient is and their signature is when someone is signing something” are just the beginning. From a tech perspective, Craft says, companies like Science 37 use processes similar to banking that include multifactor authentication, and multilevel email address signin that are primarily designed for patient safety and that privately and securely identify who patients are.

While the interfaces for these apps are left up to the designer, they—and rightfully so—have to live up to electronic signature guidance dictated by the FDA and other stakeholders.

It also fits into a larger and ongoing problem in the world of biology and pharma: The shift from paper-based recordkeeping to electronic medical records, electronic data sets and massive, multi-use databases. Stakeholders have to make sure they’re collecting the exact same data digitally as they would normally be collecting with paper, which is not the easiest thing to do.

Large-scale studies like mPower are ongoing as well; and as Apple improves their platforms, it’s inevitable that other influential industry players will try smartphone app, mass population studies. The challenge will be reconciling the expectations of patients who play high-tech smartphone games, and use communication apps like Facebook, with the design and functionality required by regulations.

Phone and tablet apps also hold the potential to work in tandem with other workflow and patient- experience improvement tools in the clinical trial world. For instance, Cancer Commons is a massive nonprofit data crowdsourcing project designed for any patient to send in a question about their cancer type, stage, or treatment and quickly receive an answer from a physician. Science 37’s efforts are also paralleled by other companies like Global Care Clinical Trials, which maintains a network of clinicians who can conduct at-home visits with patients in clinical trials, which opens opportunities for trial participation.

In the end, it’s all about the patients and how technology can improve the trial experience for them. Because mobile apps can reduce the timeframe for new products to make it to market, make the clinical trial process easier, and even help patients better understand their own conditions, they hold enormous potential. As the life sciences world becomes more comfortable with mobile apps, they’re going to become increasingly commonplace. And while they might be a novelty today, smartphones and tablets are going to become a much more prominent part of clinical trials.