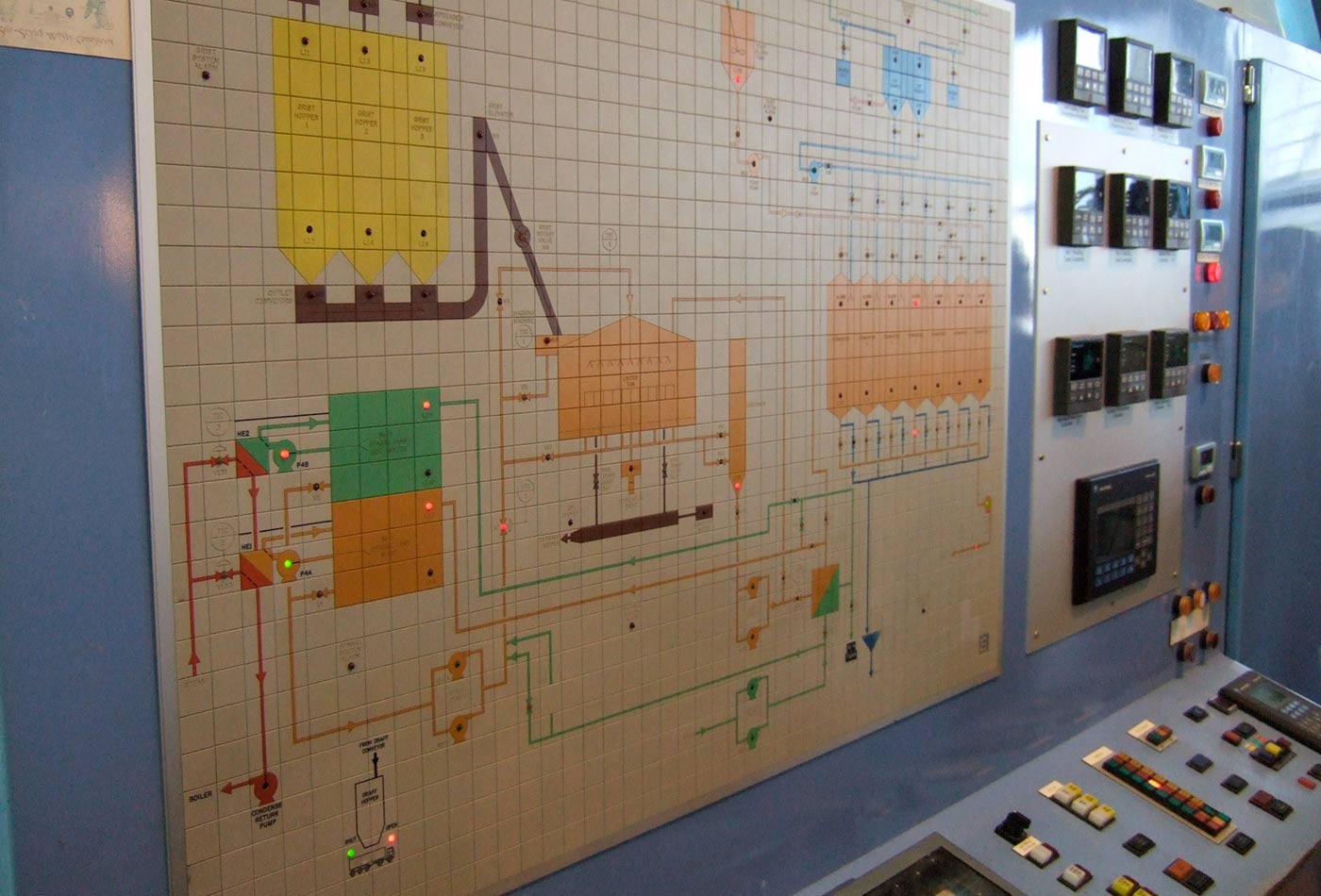

Not as small as Edradour. (source: Mike Beltzner on Flickr)

Not as small as Edradour. (source: Mike Beltzner on Flickr) Every effective database needs a carefully designed schema that keeps data clean, avoids conflicts, serves its users’ varied needs, and accommodates future extensions. In the same way, an effective corporate data program needs data governance: carefully planned policies that clarify responsibilities, resolve conflicts between different stakeholders, provide for maintenance and growth, and safeguard sensitive information.

Data governance concerns typically include:

- Long-range planning: identifying strategic needs, finding managerial sponsorship for data programs, securing multi-year budget commitments, and providing for maintenance and upgrades in addition to new features

- Architecture: anticipating and reconciling data-strategy conflicts between different business units

- Ownership: defining clear responsibility for maintenance, updates, and expansion among capability areas like development, operations, infrastructure, business intelligence, and various lines of business

- Data collection: incorporating data from various lines of business into company-wide strategy, and ensuring that data is clean at its source

- Security and compliance: identifying sensitive data and its relevant regulatory and professional requirements and implementing technical and managerial safeguards

Data-management authority Simeon Schwarz shared a thought experiment with me: imagine you’re setting up a new CRM analytics system at a stock brokerage. You ask each of the system’s stakeholders what an “account” is to them. Each answer is different:

- Marketing: “An account is a converted lead.”

- Finance: “An account, for reporting purposes, is a customer with money on deposit who can trade with us.”

- Accounting: “An account is a recorded entry in our back office, books, and records system.”

- Legal: “An account is a structured product we offer our customers through a legal agreement that they sign.”

Although each definition is correct in the view of its stakeholder, the individual definitions might not be reconcilable into a single definition of “account,” and without a data governance plan, each department’s processes are likely to treat records differently. The result is a difficult situation in which each department’s processes create a single version of the truth with its own set of regulatory and compliance risks. Reporting and analytics become unreliable and exacerbate conflicts.

The marketing department might create a new account record for every lead gathered through its web forms, leaving typos in place. The legal department might create a new record for each contract from scratch, duplicating some data and necessitating a further cleansing step if its data conflicts with the typo-filled data from the marketing department.

Perhaps the entire system runs on infrastructure controlled by the accounting department, thanks to a convention dating to the mainframe era, and the accounting department is uninterested in spending its budget to improve the marketing department’s data-collection system. And members of the marketing department are accustomed to viewing raw customer records in the accounting department’s database as they develop their campaigns, which represents a regulatory and security risk.

An ongoing data governance program provides the intellectual and institutional grounding to address these challenges, anticipate new ones, and provide for development according to the company’s strategic plan.

Key terms and trends

The introduction of the chief data officer (CDO) role is an increasingly popular response to the challenges of data governance. The CDO is the executive responsible for data governance, and the addition of a CDO to a company’s executive committee is an expression of the centrality of data to its value and mission.

Industry organizations and vendors have developed a variety of data governance frameworks. Among the most prominent is The Open Group Architecture Framework (TOGAF), based on an earlier effort of the U.S. Department of Defense. The scope of TOGAF goes well beyond data governance, but data architecture is a well-documented component of the framework. The Data Governance Framework (DGI) is another structured perspective on governance.

In addition to the “framework” approach, there are early research projects on the potential use of metadata and context services for formulating governance policies—a bottom-up rather than top-down perspective on the problem.

Safari resources

- Data Governance by John Adler. A deep overview of the challenges of data governance and practical ways to address them. Includes guidance on how to structure and approach the role of Chief Data Officer.

- Understanding the Chief Data Officer, 2nd Ed. by Julie Steele. An introduction to the role of chief data officer, with practical profiles of CDOs at Wells Fargo, Samsung, the Republican National Committee, Allstate, and the Federal Reserve Board.

- Security, Privacy, and Governance O’Reilly video collection. Drawn from popular talks at the Strata + Hadoop World conferences, this collection surveys several of the challenges that are central to data governance, including security considerations for Hadoop and machine learning, compliance for regulated industries, and privacy.

- Modeling Enterprise Architecture with TOGAF by Philippe Desfray and Gilbert Raymond. A full guide to understanding The Open Group Architecture Framework, a leading approach for enterprise architecture.