One man willingly gave Google his data. See what happened next.

Google requires quid for its quo, but it offers something many don’t: user data access.

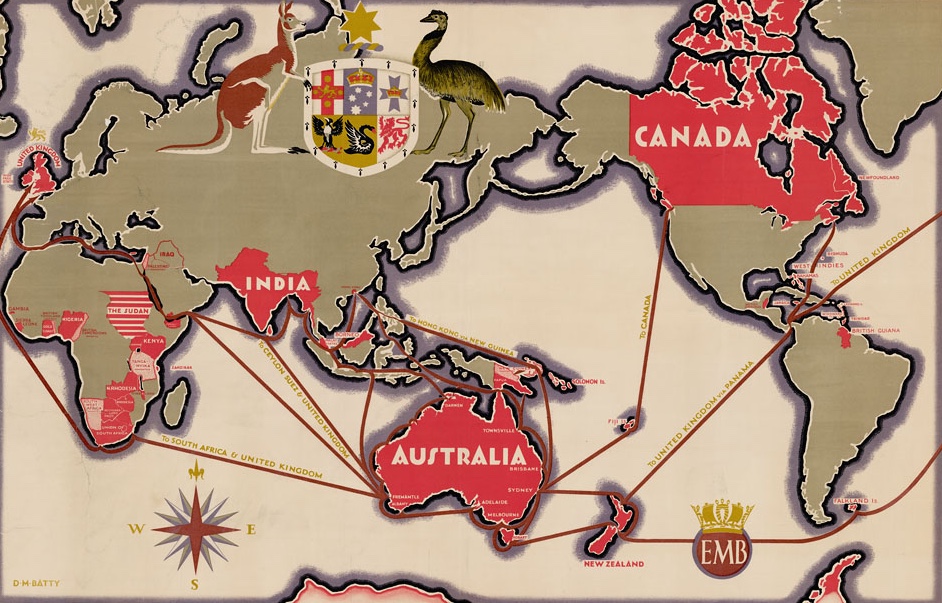

Shipping Lanes (source: BiblioArchives)

Shipping Lanes (source: BiblioArchives)

Despite some misgivings about the company’s product course and service permanence (I was an early and fanatical user of Google Wave), my relationship with Google is one of mutual symbiosis. Its “better mousetrap” approach to products and services, the width and breadth of online, mobile, and behind-the-scenes offerings saves me countless hours every week in exchange for a slice of my private life, laid bare before its algorithms and analyzed for marketing purposes.

I am writing this on a Chromebook by a lake, using Google Docs and images in Google Drive. I found my way here, through the thick underbrush along a long since forgotten former fishmonger’s trail, on Google Maps after Google Now offered me a glimpse of the place as one of the recommended local attractions.

Admittedly, having my documents, my photos, my to-do lists, contacts, and much more on Google, depending on it as a research tool and mail client, map provider and domain host, is scary. And as much as I understand my dependence on Google to carry the potential for problems, the fact remains that none of those dependencies, not one shred of data, and certainly not one iota of my private life, is known to the company without my explicit, active, consent.

Just a few weeks ago saw me, once again, doing the new gadget dance. After carefully opening the box and taking in that new phone smell, I went through the onboarding for three phones — Windows, iOS, and Android — for a project. Letting the fingers do the dance they so well know by now, I nevertheless stop every time to read the consent screens offered to me by Apple, Google, and others. “Would you like to receive an email every day reminding you to pay us more money?” — No. “Would you like to sign up for an amazing newsletter containing no news but lots of letters?” — No. “Google needs to periodically store your location to improve your search suggestions, route recommendations, and more” — Yes.

“You would never believe what Google secretly knows about you,” says the headline in my Facebook feed. Six of my friends have so far re-shared it, each of whom expresses their dismay about yet another breach of privacy, inevitably containing sentence fragments such as “in a post-Snowden world” and calling Google’s storage and visualization of a user’s location data “creepy.”

This is where the narrative, one about privacy and underhanded dealings, splits from reality. Reality comes with consent screens like the one pictured to the right and a “Learn more” link. In reality the “creepy” part of this event isn’t Google’s visualization of consensually shared data on its Location History page, it’s the fact that the men and women whom I hold in high esteem as tech pundits and bloggers, apparently click consent screens without reading them. Given the publicity of Latitude on release and every subsequent rebranding and reshaping, and an average of 18 months between device onboarding for the average geek, it takes quite a willful ignorance to not be aware of this feature.

And a feature it is. For me and Google both. Google gets to know where I have been, allowing it to build the better mousetrap it needs to keep me entertained, engaged, and receptive to advertisement. Apparently this approach works: at $16 billion for the second quarter of this year, Google can’t complain about lack of sales.

I get tools and data for my own use as well. Unlike Facebook, OKCupid, Path, and others, Google even gives me a choice and access to my own data at any time. I can start or stop its collection, delete it in its entirety, and export it at any time.

The issue here isn’t with Google at all and, at the same time, one of Google’s making. By becoming ubiquitous and hard to avoid, offering powerful yet easy-to-use tools, Google becomes to many a proof-positive application of Clarke’s Third Law: indistinguishable from magic.

Not one shred of data, not one iota of my private life, is known to Google without my explicit consent.

And, like magic, lifting the curtain isn’t something many entertain. Clicking the “read more” link, finding links to Google’s Dashboard, Location History, and Takeout seems to have been a move so foreign even tech pundits never attempted it. Anyone finding their data on Google’s Location History page once consented to the terms of that transaction: Google gets data, user gets better search, better location services, and — in the form of that Location History Page — a fancy visualization and exportable data to boot.

Can Google be faulted for this? Yes, a little bit. Onboarding is one of those things we do more or less on auto pilot. Users assume that declining a consent screen will deprive them of features on their mobile devices. In the case of Google’s Location History that’s even true, free magic in exchange for a user’s life, laid bare before the dissecting data scalpels of the company’s algorithm factory.

There is no such thing as a free lunch. We are Google’s product, a packaged and well-received $16 billion cluster of humans, sharing our lives with a search engine. Strike Google, replace value and function, and the same could be said for any free service on the Internet, from magazine to search engine, social network to picture-sharing site. In all those cases, however, only Google offers as comprehensive a toolbox for those willing to sign the deal, data for utility.

This makes Google inherently more attackable. The Location History visualizer provides exactly the kind of visceral link (“check out what Google is doing to your phone, you won’t believe what I found out they know about you”) to show the vastness of the company’s data storage; that’s tangible, rather than Facebook’s blanket “we never delete anything.” Hint to the next scare headline writer: Google doesn’t just do this for Location, either. Search history traces, if enabled and not deleted, back to the first search our logged-in selves performed on the site (my first recorded, incidentally, was a search for PHPs implode function on April 21, 2005). YouTube viewing history? My first video was (I am now properly ashamed) a funny cat one.

Google doesn’t forget. Unless asked to do so, which is more than can be expected from many of the other services out there. That dashboard link, so prominent on every help page linked from each of Google’s consent screens, contains tools to pause, resume, delete, or download our history.

Google’s quo, the collection of data about me to market to me and show me “relevant” ads on Gmail, YouTube, and Search, as well as the ever-growing number of sites running AdWords, begets my quid — better search, better recommendations for more funny cat videos, and an understanding that my search for “explode” might concern PHP, not beached whales.

If there is a click bait headline that should make it onto Facebook, it’s not this fake outrage about consensual data collection. It should be one about consent screens. Or, better, one about an amazing lifesaver you have to try out that takes your location history, runs it through a KML to GPX converter, and uses it to reverse geotag all those pictures your $2,000 DSLR didn’t because the $600 attachment GPS once again failed. Here’s how to do it:

- Open Google Location History and find the download link for the day in question. To add more data points click the “Show all points” link before downloading the KML file.

- Convert the file to GPX. Most reverse geocoders can not read KML, which means we’ll have to convert this file into GPX. Luckily there are a number of solutions, the easiest by far is using a GPX2KML.com. Change the encoding direction in the dropdown, upload your KML file, download the converted GPX.

- Use a Geocoding application. Jeffrey Friedl’s “Geocode” plugin for Lightroom 5 (and possibly 4) does a good job at this, as does Lightroom 5’s built in mechanism. Personally I use Geotag, a free (open source) Java application which also allows me to correct false locations due to jitter before coding my photos.

- There is no step 4. Enjoy your freshly geocoded images courtesy of Google’s quo for your quid.