Programming, oaths, and users

The Programmer's Oath is missing one essential element: the customer.

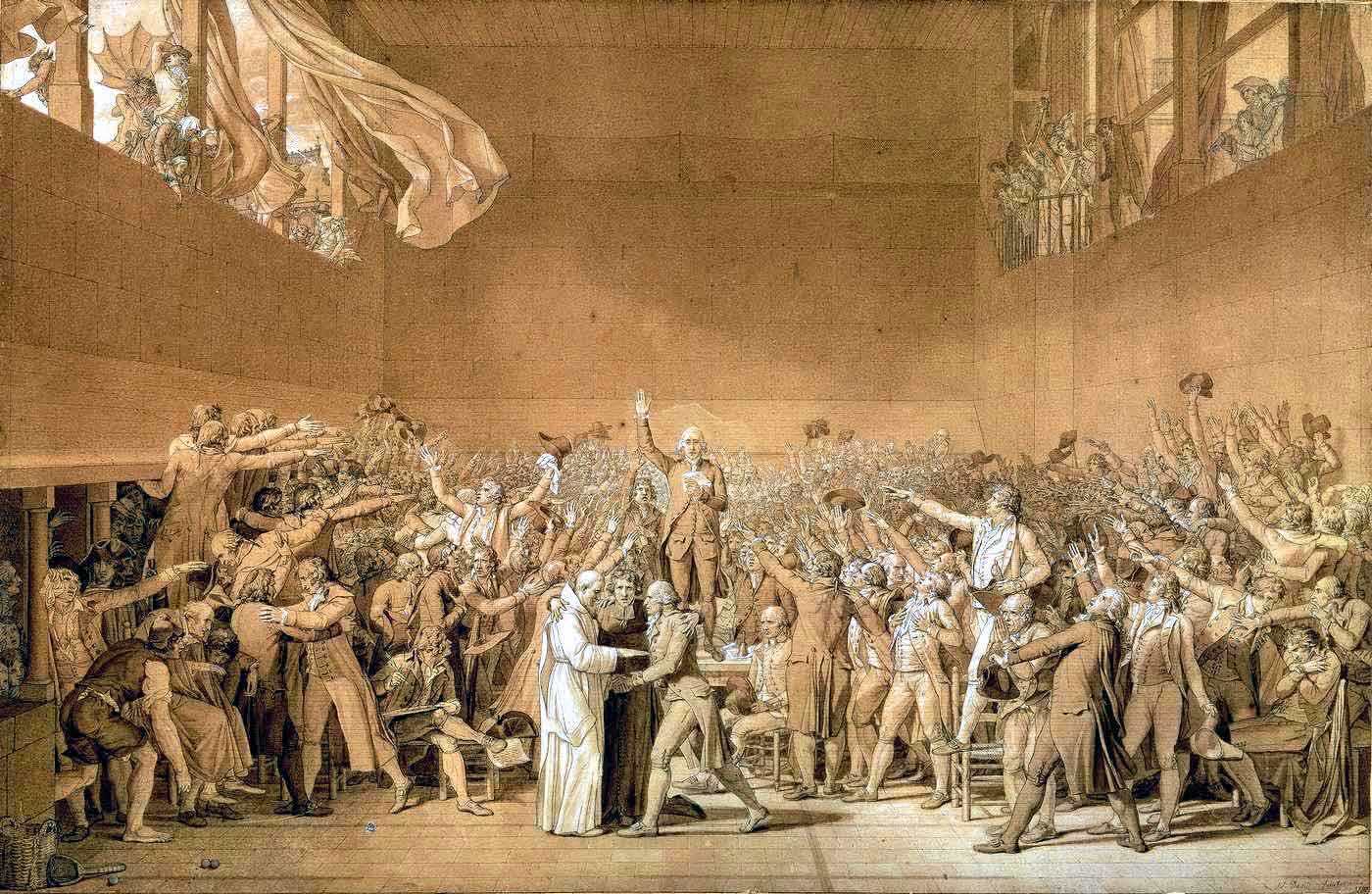

Le Serment du Jeu de paume, 1791. (source: Wikimedia Commons)

Le Serment du Jeu de paume, 1791. (source: Wikimedia Commons)

Over the Thanksgiving holiday, there was a debate between Greg Brown (@practicingdev) and Ron Jeffries (@ronjeffries) about, among other things, Uncle Bob Martin’s Programmer’s Oath. I won’t comment directly about the debate; it’s summarized in Jeffries’ “More on Uncle Bob’s Oath” and Brown’s “A Response to Ron Jeffries.” (Rote disclaimer: Greg invites me to his crazy parties. And he’s writing a book for O’Reilly on his ideas about the practice of software development. I don’t know Ron, though I’ve probably met him at a conference. If Greg invites you to a party, you should go.) But I think it’s worth taking a look at the oath.

If you compare the Programmer’s Oath to other oaths, you’ll realize that something is missing. Here’s the Girl Scout oath:

On my honor, I will try: To serve God and my country, To help people at all times, And to live by the Girl Scout Law.

And the Boy Scout oath:

On my honor, I will do my best, to do my duty, to God and my country, and to obey the Scout Law, to help other people at all times, to keep myself physically strong, mentally awake, and morally straight.

And the Presidential Oath of Office:

I do solemnly swear (or affirm) that I will faithfully execute the office of President of the United States, and will to the best of my ability, preserve, protect, and defend the Constitution of the United States.

The Programmer’s Oath has the distinction of being longer than the other oaths I’ve quoted. Despite its length, though, it’s missing an important element. Scouts of either gender are enjoined to “help people at all times.” The President is required to “preserve, protect, and defend the Constitution.” Programmers do what? Make better code. For whom? Ourselves? Our own enrichment, or our own sense of pride at a job “well done”? I see no mention of the user, the customer, or the client in the Oath. And that is very, very strange.

I imagine that someone might defend the oath by saying “well, serving the customer goes without saying.” Or, more subtly, that any improvement to the code base is in the customer’s interest, whether or not it has any effect on the software’s behavior. I don’t buy it. Oaths are all about saying things that “go without saying,” because otherwise those things don’t get said. And you probably do need to tell Scouts that they should help people. Can we take it for granted that programmers are thinking about serving their customers or delivering the best possible value for their clients? It’s easy to answer this question. Have you used software recently? We’ve got a long, long way to go on that “serving the customer” thing.

I won’t try to discuss what “serving the customer” might mean. That’s a hugely important discussion that’s been going on for years. Customers frequently don’t know what they want, what they need, or how long it might take to develop it. They often don’t even know why they want what they want. (“Hey, everyone has big data now. Can you make a Hadoop for me?”) What’s the role of a programmer in helping customers figure out what’s important? How does a programmer deliver the best business value to the people who are paying the bills?

Important questions. Without acknowledging the presence of the customer or the user, a programmers’ oath is essentially inward facing: it’s a document about self-improvement, not about service. A programmer’s oath needs to encompass the whole of what programmers do, and that’s a lot more than just programming. Oaths are about an ethic of service, and service assumes an other.

To see what a difference this might make, let’s try to add a new clause to the Programmer’s Oath, but this time, with the customer in mind. One of the most challenging articles I’ve read in the past year was Dan McKinley’s Choose Boring Technology, in which he argues for choosing older, proven technologies that are known to work, rather than “new, shiny.” Working on the newest thing that all the cool kids are using is a lot of fun, and great for your resume, but is it really good for the customer? How does it affect long-term reliability and maintainability? We could add McKinley’s principle to the Programmer’s Oath as:

I will make technology decisions based on the customer’s needs, not my own.

Do you see how different that feels from the other clauses? It’s not inward facing; it’s not about doing something that feels satisfying to you; it’s entirely about serving your customer, and doing right by them.

I don’t have any fundamental issues with any of the practices enumerated in the oath. It’s hard to object to testing, or to improving bad code. But they all need to be viewed through the lens of “does this serve the customer?” And the customer’s absence from the oath is a symptom of the problem, not the solution. Would our code be different if we thought of coding as a service to others? Would our lives be different?