Smart cities, smarter citizens

Companies are looking to transform major cities through advanced computer technologies and citizens need to play a large role in turning cities into smart, livable environments.

City at night (source: O'Reilly)

City at night (source: O'Reilly)

In Isaac Asimov’s 1954 science fiction novel, The Caves of Steel, Earth’s cities have metastasized into huge dome-covered labyrinths, providing food and shelter—but little else—for billions of miserable inhabitants.

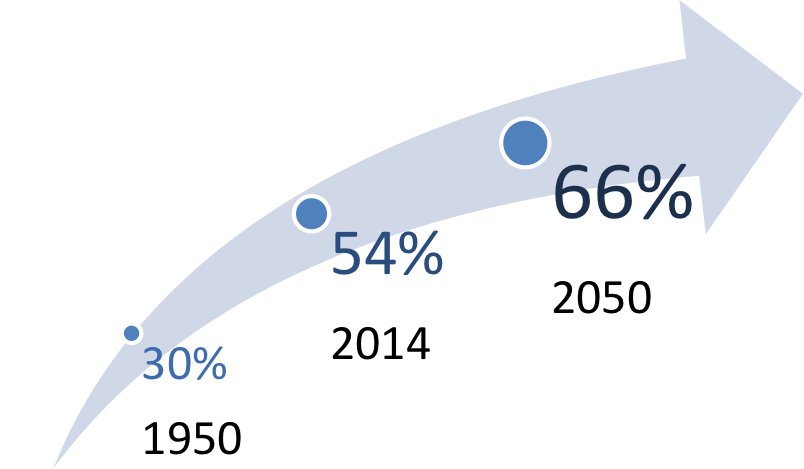

When Asimov wrote the novel, less than a third of the world’s population actually lived in cities. Today, more than half of us live in cities. By 2050, two-thirds of humanity will be city dwellers, and there will be more than 40 mega-cities boasting populations of at least 10 million.1

What will these cities of the future be like? Will they be lively centers of culture and innovation? Or will they be grim hubs of despair as depicted in movies like Metropolis and Blade Runner?

An Old Story Unfolding at a Faster Pace

Urbanization isn’t a new trend; the migration of people from rural to urban areas has been going on for millennia. What’s different today is the speed and scale of that migration. Three or four thousand years ago, you needed an oxcart and a brave heart to make the arduous journey from the hinterlands to the nearest walled settlement. Today, you can take an airplane from practically anywhere and arrive at the city of your choice in hours.

Why do people choose to live in cities? Here’s an official answer from the United Nations: Cities are nodes of “economic activity, government, commerce, transportation.” City life is commonly associated with “higher levels of literacy and education, better health, greater access to social services, and enhanced opportunities for cultural and political participation,” according to a recent UN report on global urbanization.

For many people, cities offer an escape from poverty and the everyday hazards of rural living. Moreover, cities provide complex services and rich amenities that are considered hallmarks of modern civilization, such as mass transit, sanitation, public safety, theater, and arts.

Many of the newest and fastest-growing urban areas will be in China, India, Brazil, and sub-Saharan Africa. How will those newer cities acquire the resources necessary for supporting large populations?

Providing for the material and spiritual needs of citizens isn’t cheap or easy. It takes deep pockets to build urban infrastructure and to pay for municipal services. Vast amounts of energy, material, and labor are required to keep a city running smoothly.

Smarter Services, Lower Costs

Given the high costs of running a city, it’s not surprising that many smart city initiatives focus on improving efficiency and reducing expenditures wherever possible. Global firms such as GE, Cisco, IBM, and Siemens are leading the charge to transform cities through a combination of advanced computer technologies, sensors, high-speed data networks, predictive analytics, big data, and the Internet of Things.

San Diego, California, and Jacksonville, Florida, recently announced trials of a new GE technology that uses LED street lighting to collect and analyze data. In effect, every lamppost becomes an active node in a city-wide information network, capturing and relaying data in real time about what’s going on around it. GE envisions “brilliant” information networks enabling cities to monitor traffic, manage parking, find potholes, and keep track of roadwork—mostly by modifying or enhancing existing municipal infrastructure.

The networked LEDs can also keep track of parking spaces and, in the future, will be able to notify motorists via text message when a space is empty or when their meter time is expiring. In addition to making it easier for motorists to deal with common parking hassles, these kinds of systems could reduce the need for legions of enforcement officers patrolling city streets.

Some Assembly Required

Unquestionably, technology will play a critical role in the evolution of smart cities. But technology is only one thread in a larger tapestry.

“When people talk about smart cities, they’re really talking about smart energy, smart transportation, smart healthcare, smart education,” says Samta Bansal, marketing and strategy leader for GE’s Intelligent Cities initiative. “They’re talking about many separate verticals. But what’s more important is the convergence of those verticals into a comprehensive system with citizens at the center.”

Truly “smart” cities combine services and technology to serve their citizens efficiently and generate new opportunities for them. “There’s no easy recipe for becoming a smart city,” says Bansal. “New approaches are necessary to design and implement intelligent city solutions. In addition to technology and infrastructure, you need good policy, leadership, and a regulatory framework. You need to create a thriving environment where innovation can breed.”

In the past, the difficulties of travel constrained migration. When people were forced to move, they often moved to whichever city was closest. Today, and for the foreseeable future, cities will have to compete for educated workers with top-notch skills. Smart cities, says Bansal, will attract the best and brightest.

“People can choose to live in the cities or countries that offer the most opportunities,” she says. “As a result, there will be intense competition among cities to attract the most highly skilled residents and the best companies.”

But cities can’t merely apply technology superficially and call themselves “smart.” Adding intelligence to infrastructure is one thing; engaging and involving citizens with intelligent city networks is quite another. Cities also need long-term strategies for meeting the increasingly complicated needs of workers, residents, families, and visitors. Smart city solutions must be flexible enough to address the needs of private and public organizations.

“Most cities in the U.S. want to be smart cities, but they’re only solving one problem at a time. That leads to vertical integration of services, but not to horizontal integration,” she says. Cities like Amsterdam, Copenhagen, and Dubai provide smart services that are holistic and horizontally integrated, such as healthcare, shopping, telecom, transportation, recreation, air quality monitoring, and even video gaming.

“Understanding how to create intelligent cities is only half the battle. The other half is figuring out how to turn them into better places for the people who live in them,” Bansal says.

Streetwise Data Science

Part of the evolving smart cities narrative is built around sexy new technology. But most of the real work involves data management. Politicians take credit for the success of their smart city initiatives, but the nitty-gritty details are invariably handled by data scientists and people who understand how data science can be used to solve urban problems.

Michael Flowers is the executive in residence at the NYU Center for Urban Science and Progress and the chief analytics officer at Enigma.io, a New York-based firm specializing in public data analytics.

Earlier in his career, Flowers worked for the Manhattan district attorney’s office. After a brief stint in corporate law, he volunteered to join the team of lawyers working on the trial of Saddam Hussein. From his office in Baghdad’s Green Zone, he noticed how the military used data science to figure out the best routes for avoiding IEDs (improvised explosive devices) as they traveled around the city. After returning to New York, he went to work for the administration of Mayor Michael R. Bloomberg. In 2012, he was appointed the city’s first chief analytics officer.

From his perspective, the smart city movement is less about technology and more about improving the way decisions are made in large urban areas, where the demand for services is increasing and the availability of resources is diminishing.

“The great urban migration is placing even higher levels of demand on basic city infrastructure: water, sewer, fire, police, housing, healthcare, education, parks…Meanwhile, cities have even fewer resources to meet those needs,” Flowers writes in Beyond Transparency: Open Data and the Future of Civic Innovation, a collection of essays published in 2012.

Smart cities use data to deliver critical services more efficiently. They avoid simplistic approaches to apportioning funds and shift to risk-based resource allocation strategies. They encourage and enable seamless sharing of information across agencies and departments. “Being data-driven is not primarily a challenge of technology; it is a challenge of direction and organizational leadership,” he writes.

The real goal of a smart city is delivering more services with fewer resources. That means using resources more intelligently. For example, in New York City, there is a strong correlation between property tax delinquencies and structural fires. In other words, the more a landlord owes in unpaid property taxes, the greater the likelihood of a fire breaking out in a building owned by that landlord. So it makes sense to prioritize inspections of buildings owned by landlords with tax issues. In addition to saving the lives of tenants and firefighters, it also makes the fire inspection process more efficient and less costly.

The key to success, however, is sharing data across multiple agencies. “We have no shortage of data from which to build a catastrophic risk model,” writes Flowers. The primary obstacle is legacy infrastructure. New York City, for instance, has more than 40 agencies and nearly 300,000 employees.

“There’s an important distinction between collecting data and connecting data,” he writes. “Each agency has its own ontology of terms and data…which sometimes makes it nearly impossible to connect that data. One department may use a GIS (geographic information system) identifier for the location of a downed tree, whereas another may refer to it by its cross streets.”

Despite the obstacles posed by legacy systems and existing infrastructure, you can’t ignore them or simply wish them away. “You have to understand the bureaucracy and the rhythm that it dances to,” says Flowers. “You can’t just try to hammer it down. You have to embrace the bureaucracy and weave the processes of data-driven decision making into what’s already there. You really don’t have a choice.”

Flowers points to New York City’s long-awaited Second Avenue Subway as a prime example of what happens when planners assume that technology will always find a way to triumph over bureaucracy and existing legacy infrastructure. The subway line was initially proposed in 1919 and it’s still under construction. The delays weren’t caused by technology; people have been digging tunnels for centuries. The delays resulted from a lack of cooperation between the surrounding neighborhoods and the various city agencies responsible for planning and building the subway.

Living Laboratories, Made of Steel and Concrete

“Local is the perfect scale for smart-technology innovation,” writes Anthony M. Townsend, author of Smart Cities: Big Data, Civic Hackers and the Quest for a New Utopia. In a city, it’s easier to identify problems, engage interested groups of citizens, and see the impact of new solutions than in a sprawling suburb or rural landscape. “Each of these civic laboratories is an opportunity to invent,” he writes.

There are also risks in “remodeling cities in the image of multinational corporations,” Townsend writes. When a business decides to kill an unsuccessful product or withdraw from an unprofitable market, it simply writes off its losses and moves on. Writing off or walking away from a failed smart city won’t be that easy.

But that hasn’t stopped big companies from marketing the dream of wonderfully efficient smart cities. “It’s a tough pitch to resist. For a world that seems increasingly out of kilter, rewiring cities with business technology is a seductive vision of how we can build our way back to balance,” he writes.

Chris Greer is director of the Smart Grid and Cyber-Physical Systems Program Office, and national coordinator for Smart Grid Interoperability at the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST). From his perch at NIST, he sees the smart cities movement as an important force for technology convergence. “Cities that want to be environmentally sustainable and resilient to natural disasters will focus on linking their independent infrastructures. That creates a very strong driving force for convergence of technologies,” Greer says.

Greer, like other thought leaders in the emerging Industrial Internet of Things (IIoT), sees horizontal convergence of multiple independent technologies as essential to progress on many fronts. “So if you’re looking for drivers of convergence, smart cities fit the bill,” he says.

“Typically, the goals of smart cities involve providing social benefits, such as a sustainable environment, efficient energy, reduced traffic congestion, and shorter commutes. Achieving those goals requires integrating many technology platforms. You can’t just look at one aspect of the challenge and deal with it independently,” Greer says.

In the past, a city might have looked at its power grid as an independent system. But when you consider the central importance of a power grid in times of crisis or disaster, it no longer makes sense to treat it as an isolated system. “We need to start thinking of these systems in terms of a broader community infrastructure that includes many dependent systems,” Greer advises.

Smart cities are “the right starting point for convergence,” he says. “But I think we’re seeing a market failure, in the sense that most smart cities are one-offs or custom integrations. That’s not the right approach. We need cities working together to create interoperable solutions that can be used anywhere.”

Last year, NIST helped launch the Global City Teams Challenge (GCTC) to “encourage collaboration and the development of standards.” NIST’s partners in the GCTC include US Ignite, the Department of Transportation (DoT), the National Science Foundation (NSF), the International Trade Administration (ITA), the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), and the Department of Energy (DoE); and from the private sector, Intel, IBM, Juniper Networks, Extreme Networks, Cisco, Qualcomm, GE, AT&T, and ARM Holdings.

Ideally, says Greer, a “smart city platform” based on common standards will emerge. Such a platform would enable modular or “plug and play” approaches to deploying smart city services. For some, that conjures images of cloud-based city services similar to those offered by SaaS (software-as-a-service) and PaaS (platform-as-a-service) providers. Cities would choose from menus of cloud-based services and “pay by the drink,” rather than investing to develop their own unique platforms. That kind of scenario might avoid the wasteful “one-off” approach mentioned by Greer, in which each city is forced to reinvent the wheel in its quest to become smart.

“We need to bring cities together to work on shared solutions,” Greer says. “If each city develops its own solution, we’re not really getting closer to solving the big problems.”

The idea of cloud-based smart city services is appealing for a variety of reasons, including lower development costs, faster deployments, greater flexibility, and theoretically infinite scalability. On the other hand, as Townsend notes in Smart Cities, the cloud itself is far from infallible.

“Cloud-computing outages could turn smart cities into zombies,” he writes. Imagine a smart city that depends on cloud-based biometric authentication systems to authorize entry and exit from municipal facilities. If the cloud goes down, it could take the system down with it. Millions of people might be trapped inside or outside buildings until the outage is fixed.

Another potential nightmare: An outage in the Global Positioning System satellite network could paralyze a smart city that depends on GPS to guide fleets of autonomous cars, taxis, and trucks safely through traffic, Townsend observes.

Underlying Technologies

Dreams and nightmares aside, the smart cities movement requires a solid foundation of modern digital technology. In an email, Munish Khetrapal, managing director for solutions at Cisco’s Smart+Connected Communities (S+CC) initiative, outlines the basics for a practical smart city project:

“It’s important that cities roll out an intelligent network platform to serve as the backbone for any smart city technology ecosystem or framework. An intelligent network may include both wired, wireless, data, and control capabilities; including sensors, cameras, routers, switches, data management (through people and sensors), and other equipment, as well as the capability to integrate with the thousands of applications being developed daily for all sorts of purposes, from water quality to garbage pickup, from transportation schedules to pothole reporting.

The network enables city agencies to gather information more quickly from a wide variety of sources, understand it in a relevant context-based way, and make better decisions based on that new information. Citizens will benefit by gaining greater transparency into how their city operates and also have more convenient ways to engage with city agencies from mobile devices. City visitors can more easily navigate and access the cities they visit and provide feedback to enhance the experience. And businesses can tap city information to fine-tune their efforts, engage with customers, and respond with agility to new trends as they arise.”

Khetrapal’s laundry list of essential technologies is a reminder that smart cities are creations of the modern digital era. Pretending otherwise would be short-sighted. In every city, however, the most valuable resources are invariably its human residents. Cities are about people, families, homes, and jobs.

Smart cities will be inhabited by a new generation of digital natives who are fully accustomed to interacting with their surrounding environments through digital apps. The quality and reliability of those apps will likely determine the success or failure of a smart city. Maybe smart cities should consider calling themselves “smart app cities.”

When Data Is Worth More Than Gold

The people who live and work in smart cities aren’t merely consumers of data—they are also creators of data. The give-and-take between a city’s digital assets and its citizens will be absolutely fundamental.

In Portland, Oregon, for example, a local startup has launched a smartphone app called Ride Report that collects bicycle ridership data, automatically and inexpensively. The point of the app isn’t merely collecting data; the goal is providing the city leaders with quantitative information that will help them make better decisions about managing bicycle traffic in a city where practically everyone rides a bike.

The system combines Bluetooth technology with cheap sensors to count passing cyclists. The sensors then relay the information they gather to a cloud-based system. The technology is cool, but what’s cooler is how it converts the behavioral patterns of local bicycle riders into information that can be analyzed and used to improve city life.

A Connecticut startup called SeeClickFix began in 2008 as a tool for dealing with local concerns in New Haven. “We created a tool for enabling residents and government officials to work together to solve problems,” says Ben Berkowitz, the firm’s CEO and founder. “When we looked at the traditional ways that citizens communicate with government, we saw a missed opportunity to use the social web as a communications platform for sharing and documenting neighborhood concerns.”

In the past, city residents typically expressed concerns to government officials by sending letters, making phone calls, or attending public meetings. Those traditional methods, however, tended to produce a series of one-to-one conversations between a concerned resident and a city official. Berkowitz and his team had a gut feeling that if those conversations took place over a network, they would create a feedback loop, and better results would follow. Their instincts proved correct.

“When government officials come to the table on SeeClickFix and they see the common concerns of residents, they start responding. And they’re thinking, ‘Those residents aren’t complaining, they’re actually helping us do our job better.’ And they also see that the residents are grateful when problems are solved. All of this wouldn’t be possible without social web enablement on mobile devices,” says Berkowitz.

SeeClickFix has grown from an idea into a company with 30 employees. It has expanded its market beyond New Haven, and is now used in municipalities in Massachusetts, New York, and California. In many ways, it’s a model for the future of smart city technology.

“Smart cities isn’t just about instrumenting everything and creating some kind of centralized government control. It’s about getting data to people and understanding that people are also sources of data,” says Jennifer Pahlka, founder and executive director of Code for America, a non-profit organization that has been described as “the technology world’s equivalent of the Peace Corps.”

Code for America builds open source technology and organizes networks of volunteers “dedicated to making government services simple, effective, and easy to use.” For example, Code for America volunteers partnered with the city of New Orleans to create a website for tracking the status of properties that had been damaged during Hurricane Katrina and were still awaiting repair or demolition.

The city had plenty of data about the condition and status of blighted properties, but the data was spread out across multiple silos. Some of the data was in spreadsheets; some was stored on individual computers used by city inspectors.

The volunteers built BlightStatus, a simple system for aggregating data and making it accessible to city residents. “Basically, we tied together a bunch of disparate data sources,” Pahlka says. “BlightStatus lets residents go online and find out easily what’s going on with blighted properties in their local communities.”

At the heart of Code for America is the belief that digital government costs less and does a better job of delivering services than traditional government. That makes Code for America and the smart cities movement a natural fit.

Julia Kloiber of Code for Germany shares Pahlka’s belief that ordinary citizens can bring extraordinary value to the table. Code for Germany is a part of the Open Knowledge Foundation of Germany and partners with Code for America.

“Code for Germany is not so much about Smart Cities as it is about smart citizens,” says Kloiber. “We’re really about building tools for neighborhoods and to make sure that information collected by smart city sensors is made available to the public through APIs (application programming interfaces) and that the data is open by default.”

Too often, says Kloiber, public data is stored in formats that are hard to download or that cannot be easily read by machine learning programs. If the public cannot access data easily, is it fair to call that data “open data?”

Open data should be easily accessible to citizens, and not just for the sake of political correctness or elevated cool factor. When citizens have access to city data—when it is genuinely open—they can use it to help the city provide services that are more effective, more relevant, and less expensive. For example, Remix, which began as a Code for America project, is a tech startup specializing in transit planning. Here’s a brief snippet from the Remix website:

“With Remix, you can sketch out routes in any city and immediately understand the cost and demographic impact of a proposed change. We automatically pull in your existing bus lines onto the map and let you quickly design different scenarios using the latest US Census data. When you’re done, you can export to Excel, shapefiles, or even GTFS. Everything runs in your browser, and works great with the tools you already have.”

Public-minded startups like Remix are driven by open data. Rather than seeing data as a source of great wealth—“the new oil,” as McKinsey famously called it—they tend to see data as the raw material of innovation. This two-minute demo illustrates the appeal of smart city apps based on open data resources.

Emma Mulqueeny, the founder and CEO of Young Rewired State, recounts a wonderful story about teaching children in a London school to build apps for analyzing police data. The students liked the idea of learning to code. But what they liked even more, she recalls, was using the police data to plot the safest routes for walking home from school. For the schoolchildren, the open data was worth more than gold. It granted them a sense of power, and made them feel safer in their city.

Building Cities of the Future, Today

Eric McNulty is director of research and professional programs at the National Preparedness Leadership Initiative (NPLI), a joint venture of the Harvard School of Public Health’s Division of Policy Translation and Leadership Development and the Harvard Kennedy School’s Center for Public Leadership.

McNulty is the author of “Leading the Future City,” a 2012 white paper in which he envisions four types of smart cities:

- Legacities

- Technotopias

- McCities

- Cities of Desire

“Rome, London, New York, and Paris are examples of Legacities. They’ve been around for a long time and they have established infrastructures that need to be updated rather than built from scratch,” he says.

Cities like Dubai, Singapore, and Songdo are examples of Technotopias. “They are newly built urban areas with the latest technology and infrastructure, which they use to attract talent and compete aggressively for companies,” he says. “They’ve got the fastest Internet and the tallest buildings.”

McCities tend to resemble old-fashioned cities of the 1950s, with endless blocks of similar apartment buildings and office towers. “They are built to accommodate rapidly growing populations, but they rely on traditional construction techniques and materials. They aren’t technology paradises, but they are built with the modern economy in mind,” McNulty says. “You find McCities in China and India, where urbanization is transforming society at an astonishing pace.”

Cities of Desire are sprawling slums and squatter communities. “They are the favelas of Rio de Janeiro, the Dharavi section of Mumbai, and the outskirts of Shenzhen. Even in those cities, there is often less poverty than in rural areas. And despite the density, chaos, and uncertainty of those cities, they are full of hope and aspiration,” he says.

The four types of cities McNulty describes might seem very different on the surface, but their residents share key characteristics: They use mobile phones, they are digital savants, and they believe that smart cities offer the best opportunities for building better lives.

“Smart city initiatives are not about technology,” says Khetrapal. “What makes a city unique is its culture and its people. The technology solution will need to support the systems and processes that allow that city to retain its uniqueness. Before a city begins a smart city initiative, its leaders need to identify the challenges the city faces. They must be ready and willing to look at the way its systems, services, policies, and procedures are working, or not working. The right technology solutions will focus on addressing the challenges defined by that city’s unique nature.”

1World Urbanization Prospects: The 2014 Revision, Highlights (ST/ESA/SER.A/352).

Social Physics, Idea Flow, and Engagement

Alex “Sandy” Pentland is the director of MIT’s Human Dynamics Laboratory and the MIT Media Lab Entrepreneurship Program. He advises the World Economic Forum, Nissan Motor Corporation, and a variety of start-up firms. Pentland is an oft-cited pioneer in computational social science, organizational engineering, and mobile computing.

“Studies of primitive human groups reinforce the idea that social interactions are central to how humans harvest information and make decisions,” he writes in his 2014 book, Social Physics: How Social Networks Can Make Us Smarter. Social physics is a quantitative social science revealing “how ideas flow from person to person through the mechanism of social learning,” he writes. It’s the idea flow that eventually shapes the “norms, productivity, and creative output of our companies, cities, and societies.”

Smart cities that don’t take idea flow into account are unlikely to succeed over time, because “the spread and combination of new ideas is what drives behavior change and innovation,” he writes.

“One of my former students did a study in the UK…He found that you can predict the health of neighborhoods with startling accuracy by just looking at their patterns of telephone communication,” says Pentland. “You can predict infant mortality in a neighborhood just by looking at phone records.”

A neighborhood’s levels of engagement with the communities around it and its willingness of its residents to explore other neighborhoods are also critical, he says. “You can predict crime in a neighborhood by patterns of movement and by looking at how many people from other neighborhoods visit. Neighborhoods that are more engaged with other neighborhoods have less crime; neighborhoods that are less engaged have more crime.”

For Pentland, engagement means people exchanging ideas, and then deciding as a community which ideas are good and which are bad. Exploration means bringing new ideas into the community. “Idea flow is really the source of human genius,” he says. “The richest form of communication is face to face.”

Since face-to-face communication is almost always dependent on travel, a good transportation system will generally contribute more to a city’s well-being than a high-speed digital communications hub. In Pentland’s analysis, core services such as sanitation, safety, and transportation are more important than wireless hotspots and infrared sensors.

“A lot of the smart city projects seem to focus more on technology than on people,” says Pentland. “They’re not talking about how people actually live. They’re implicitly assuming the structure of life won’t change and that we’ll just keep waking up in the morning, sending our kids to school, and going off to work. But the ways we live and work will change over the next decades.”

People want to live in cities that are resilient, creative, innovative, adaptive, and supportive. “A city should be robust in the social sense, providing support to citizens in good times and bad times,” he says.