The validated learning process for building a hardware startup

How to validate your idea and get your community engaged.

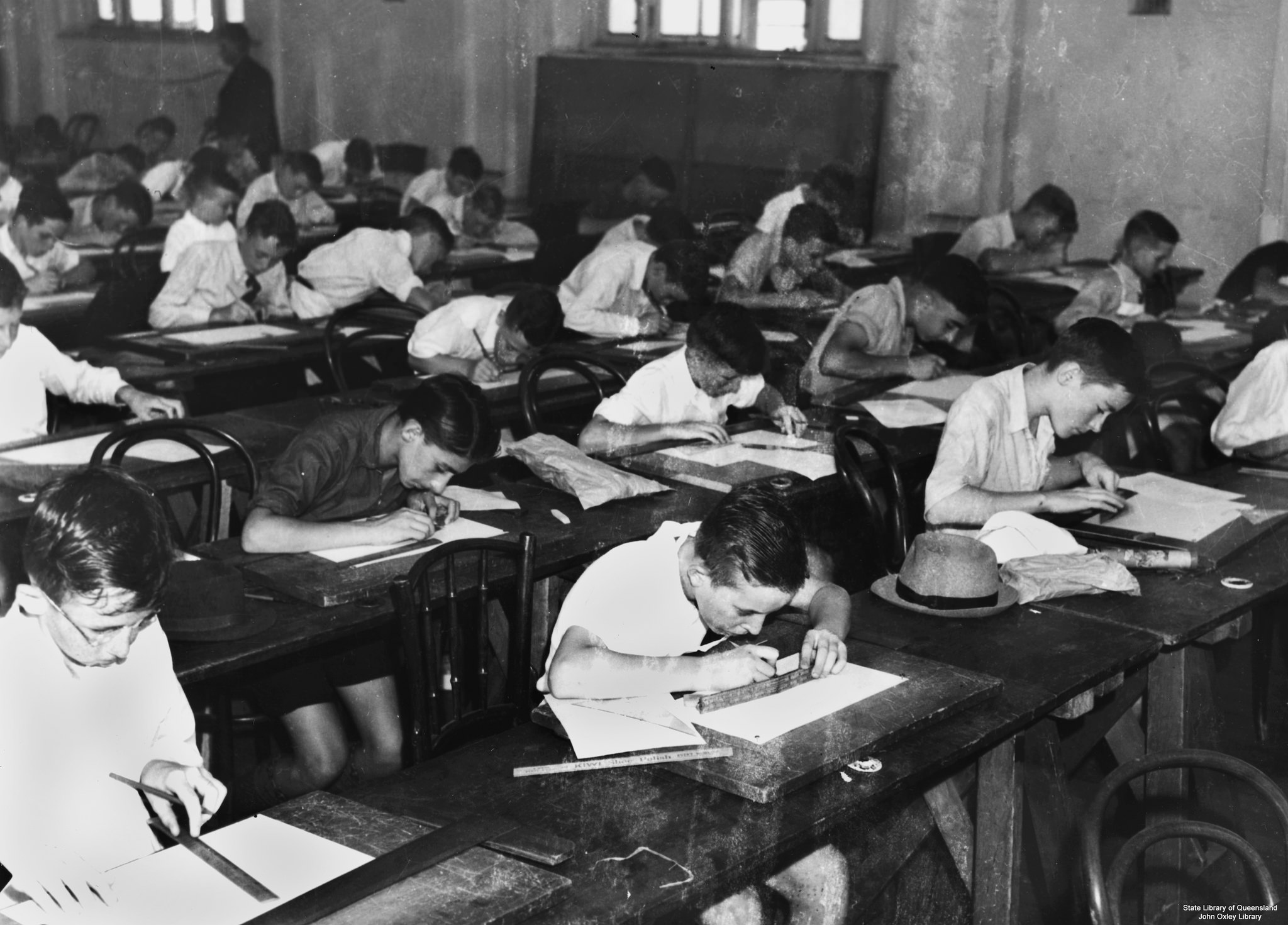

State Library of Queensland (source: Flickr)

State Library of Queensland (source: Flickr)

Buy “The Hardware Startup: Building Your Product, Business, and Brand,” by Renee DiResta, Brady Forrest, and Ryan Vinyard. Note: this post is an excerpt from the book.

Hardware founders should strive for hypothesis-driven development and validate their ideas with customers as early as possible. This can be done before or alongside the prototyping process, but it should absolutely be done before moving toward tooling.

Changing your design or switching technologies becomes much more expensive once you’ve moved beyond a prototype, so it’s important to get it right the first time.

The foundation of effective validated learning is conversation. You want to talk to — and, more importantly, listen to — several distinct groups of people who will be critical to your success as a company.

Your fellow hardwarians

The first group of helpers on the road to building your product are fellow hardware founders. Not everyone within the hardware community is a potential customer who will help you unearth the roots of a particular pain point. But within this community are the people who have done it before. They have extensive experience and can provide invaluable guidance for specific problems. They’ll help you reduce waste in the production process. Certain steps in the development process, such as finding a contract manufacturer, are often driven by word-of-mouth referrals. Networking with other founders building products in your space will give you a better chance of getting these things right the first time.

Many first-time hardware founders are coming from software, or are hobbyist makers who haven’t developed extensive personal networks within the hardware startup community. Fortunately, it’s easier than ever to find fellow hardwarians. Although online communities can have strong ties, they aren’t a substitute for a local network. Even if you live in a smaller town, meeting fellow hardware hackers nearby can help you discover facilities, suppliers, and other resources. These connections are particularly valuable early on because you’ll likely be prototyping locally.

The Hackerspace Wiki is a great resource for finding like-minded people, and it has the added benefit of potentially helping you discover a shared workspace or machine shop. See if there’s a TechShop or FabLab in your area. In addition to teaching classes, these spots often host community events such as show-and-tells and happy hours. The Hardware Startup Wiki and The Maker Map can also help you discover what’s happening locally; these two sites are maintained in part by the authors of this book, but they rely heavily on community contribution.

Your co-founder and team

If you already have a co-founder, or an early founding team, that’s awesome! If not, you’re going to need to find one. It can take several months to convince someone to join your team, particularly if you haven’t received funding. A co-founder relationship is like a marriage: you’re going to be building a company with this person for years, so it’s important to find an equally committed partner and establish good channels of communication right from the start.

If you’re looking for a co-founder, consider signing up for a co-founder matching community such as FounderDating, CoFoundersLab, or Collab-Finder.

Building a well-rounded team right from the start is crucial. In the early days, this involves finding people you work well with, who have complementary skill sets. Know what you yourself bring to the table as well as what you need. At a minimum, you need one founder with hardware experience and another with business experience (or a second technical founder who’s willing to learn).

If you’re technical, you probably have a good sense of what it takes to build a product. However, you might not understand sales, branding, or marketing very well, and at some point, someone needs to convince people to buy your device. Having a well-rounded business development person as an early team member can help ensure that you don’t neglect this critical part of company-building.

If you’re a nontechnical founder, you absolutely must recruit a technical partner. It will be virtually impossible to raise funding or efficiently get to market without one (in terms of both time and cost). A technical co-founder shouldn’t be a hired gun who you bring on to build your idea. You need to attract a teammate who shares your vision and wants to partner with you. Sales and finance experience isn’t particularly useful in the early days of the company, so it’s important to spec out specifically what you will be doing while your co-founder builds.

If you’re planning to build a connected device, wearable, or any product that interfaces with your customer via software, you’ll want to bring on a software engineer as early as possible, preferably one with some UI/UX design experience. Software is the arena where a hardware company can continue to innovate even after the physical product has been shipped, which is incredibly important. Some founders choose to outsource software development in the beginning, but you’ll need to line up someone to own that critical product role fairly early on.

It’s beneficial to build a pipeline of potential talent right from the start. Talent acquisition is yet another reason to get plugged into your local hardware community. Increasingly common in most cities, hackathons are a great low-pressure way to work on a project and meet people. If you went to a university with a strong alumni network, join your school’s listserve or LinkedIn group.

Your LinkedIn connections are a powerful resource to leverage. The broader your network, the more likely you’ll find potential teammates with the skill set you’re looking for. If you see someone you’d like to meet, ask for an introduction from a shared contact, even if you’re not immediately hiring.

As you begin to meet people, be open. Keeping your idea a secret won’t get you very far. If you’re passionate about your vision, talk about it with the potential teammates you’re meeting. You need to know if their vision aligns with yours. Ideally, they’ll bring their own ideas about the product to the table as well. When building a founding team, you’re looking for collaborators, not people who will rely on you to make all of the decisions and drive 100% of the early development.

Once you’ve connected with potential teammates, work on some small projects to see if you mesh well together. Founder incompatibility is one of the most common reasons young companies fail. You must discuss the questions of equity splits and division of labor as early as possible. Putting it off isn’t going to make the conversation any easier.

One common concern is commitment: are both/all co-founders quitting their jobs to do this full time? Quitting a paying job before funding is secured is risky, but a founder who does so is able to devote 100% of his or her time and attention to launching the new company. If one founder is working on the startup full-time while the other is still at another paying job, it is common for the founder(s) who took the risk to get more of the equity.

Your mentors

Another group of people to reach out to early in the idea stage are potential mentors. A good mentor will offer meaningful advice and help you work through challenges. He or she will typically have experience in some facet of your market or business. A mentor might have a particular skill set (for example, a marketing expert), deep domain knowledge (for instance, a doctor who specializes in the ailment your device remedies), years of experience, or valuable industry connections. For a first-time hardware entrepreneur, building a close relationship with someone who has been through the process of manufacturing a product (and knows the pitfalls to avoid) is invaluable. As is the case with fellow hardwarians, a mentor can also help you reduce waste and prevent overburden in your production process.

Reaching out to potential mentors can be daunting, particularly if you’re doing so via a cold email. People with a lot of experience are often in senior leadership roles and might seem inaccessible. For most of them, time is a valuable commodity in short supply. Therefore, your approach really matters. Telling someone you want him to be your mentor right off the bat is the wrong approach; it’s like proposing marriage on the first date. Strong mentor relationships develop over time. When you reach out for the first time, follow these pointers:

- Keep the email or message concise and to the point. Long emails are often ignored, or the recipient postpones reading them until it’s convenient.

- Tell the person why you’re reaching out to them specifically, to avoid the impression that your email is a mass mailing.

- Be clear with your ask. Ask for help with a discrete question or clearly defined problem. Ideally, this should be something that justifies a personal response, rather than an issue they have already addressed in a blog post or other public source of information.

- Minimize friction by offering to accommodate their schedule and preferred mode of communication.

Some startup founders choose to formalize an advisory relationship and recognize a mentor’s contribution by awarding a small equity stake in the company. This should involve a formal contract, in which the founder and mentor agree on the specific level of engagement that the mentor is expected to maintain. Monthly meetings or calls are considered standard. Strategic help, such as participation in recruiting or introduction to customers, or expert value-adds, such as work on a particular project, typically increase the amount of equity offered.

Don’t make the mistake of choosing advisors because they are famous and you want their picture on a slide to impress investors. If you’re going to give away part of your company to this person, make sure they’re doing enough work to merit the award. Be sure that your advisory contract includes criteria for termination in case the relationship goes sour and the advisor doesn’t deliver, or if you pivot into a space in which the advisor’s expertise is no longer relevant.

Your True Believers and early community

Your True Believers are your earliest evangelists. They’re the people who care enough to actively help you on the road to success, right from the start. The core of this group is usually your personal friends and family.

Gathering your True Believers requires taking a close look at your personal network. Start small: tell your closest friends and family what you’re doing and ask if they’d be interested in regular updates. Then, widen the circle. If you already have a following on social media channels, leverage it: tweet, post, drive friends and followers to a landing page with a forum or email list signup. Identify the influencers in your network who will likely be interested in your project, and reach out to them individually via a dedicated note. Tell them what you’re doing and why you’re excited about it.

There’s no magic ideal number of True Believers. However, since one of the functions of this group is to help you get the word out, increasing the number of True Believers can increase your reach, so it’s worth spending time cultivating these relationships. The more engaged this group is, the easier it will be to successfully run a crowdfunding or preorder campaign down the road. You should start to involve the people with whom you have a strong relationship as early as possible, even if you don’t have much to share at first.

True Believers are a subset of a bigger group: your early-adopter community. Communities typically form around interests, practices (for instance, hobbies or professions), or location (geographic proximity). Sometimes, they are working toward a shared goal and can be considered communities of action. Or, alternatively, they might be bound by shared circumstances, such as sexual orientation. It’s important to identify why your earliest adopters should want to spend their time participating in your community. What will they get out of the experience? They are probably interested in your product, but they won’t want to spend a big chunk of their free time endlessly discussing something that doesn’t exist yet. While True Believers care about you, the slightly broader early adopter community generally cares deeply about your space. As a result, they’re an excellent source of unvarnished feedback for early idea validation.

Getting a new community off the ground can feel like an insurmountable obstacle; it’s really hard to build a group from nothing. To grow your community beyond the True Believers who love you, you’ll have to put some effort into extending and strengthening your network. If you don’t have a strong circle of contacts, or have avoided developing a presence on popular social channels, consider putting in a small amount of time each day to foster one. You don’t have to become a social media guru, but having a rich network can only help you.

Establish relationships by participating in online groups. Post interesting content on Twitter, and engage with people who are commenting or sharing articles about your space. Google a wide variety of keywords and phrases, see what blogs or sites exist, and reach out to the authors. Look for in-person meetups. If you don’t find any, set one up. You might find kindred spirits in academia as well; for example, many universities have robotics and other hardware-focused clubs.

Once you’ve identified a handful of potential early adopters, it’s time to facilitate dialogue and begin turning the group into a true community. Introduce the members to each other and seed a conversation. You’re going to have to do the work of keeping conversations going until there are enough engaged users that it happens organically. Tailor your early content accordingly. To the extent that you’re comfortable, talk about the development process you’re going through, and solicit feedback (again: idea validation!). Passionate community members will enjoy feeling like they’re part of the process. You should try to maintain a level of excitement that will keep them evangelizing for you through what is potentially a long path to market.

Work hard to avoid making your community discussions all about you or your product because that will get boring quickly. Discuss the broader industry or space. Share news articles about the underlying issues you all care about. Call attention to the milestones or successes of the other members of the group. Above all, make your True Believers and early adopters feel valued and heard. Consider offering special perks to show appreciation, particularly as you begin to take pre-orders or ramp up to a crowdfunding campaign.

To keep the group growing, encourage early members to refer trusted contacts from their own networks. Reach out to your top community members individually to ask if there’s anyone you should invite to participate in the group. Having an invitation-only model in the beginning can help you control the size and tone as well as establish community norms. As the group grows and you no longer have to personally drive engagement, you can make it public and open and begin to promote it.

It’s easy to host your group using one of the many free tools available online. Setting up a Google or Facebook group is quick and effortless. Creating a Ning or blog-based forum requires more work, but it’s more customizable. It’s also likely to rank high in search results, which can help people to find you.

If you have a project that will appeal to a very technical or Maker-oriented audience, consider creating a forum on Instructables. Whatever platform you choose, make sure it’s a format that your community is receptive to. Once the community is public, be sure to facilitate easy sharing of content to other networks, so that others can discover you.

Related:

- Brady Forrest and Renee DiResta on Advising Hardware Startups — podcast

- Bazillion Dollar Club on SyFy

- Watch a fireside chat featuring authors Renee DiResta, Brady Forrest, and Ryan Vinyard from Solid 2015:

Public domain image on article and category pages via Pixabay.