Chapter 1. What Is Cloud Native Infrastructure?

Infrastructure is all the software and hardware that support applications.1 This includes data centers, operating systems, deployment pipelines, configuration management, and any system or software needed to support the life cycle of applications.

Countless time and money has been spent on infrastructure. Through years of evolving the technology and refining practices, some companies have been able to run infrastructure and applications at massive scale and with renowned agility. Efficiently running infrastructure accelerates business by enabling faster iteration and shorter times to market.

Cloud native infrastructure is a requirement to effectively run cloud native applications. Without the right design and practices to manage infrastructure, even the best cloud native application can go to waste. Immense scale is not a prerequisite to follow the practices laid out in this book, but if you want to reap the rewards of the cloud, you should heed the experience of those who have pioneered these patterns.

Before we explore how to build infrastructure designed to run applications in the cloud, we need to understand how we got where we are. First, we’ll discuss the benefits of adopting cloud native practices. Next, we’ll look at a brief history of infrastructure and then discuss features of the next stage, called “cloud native,” and how it relates to your applications, the platform where it runs, and your business.

Once you understand the problem, we’ll show you the solution and how to implement it.

Cloud Native Benefits

The benefits of adopting the patterns in this book are numerous. They are modeled after successful companies such as Google, Netflix, and Amazon—not that the patterns alone guaranteed their success, but they provided the scalability and agility these companies needed to succeed.

By choosing to run your infrastructure in a public cloud, you are able to produce value faster and focus on your business objectives. Building only what you need to create your product, and consuming services from other providers, keeps your lead time small and agility high. Some people may be hesitant because of “vendor lock-in,” but the worst kind of lock-in is the one you build yourself. See Appendix B for more information about different types of lock-in and what you should do about it.

Consuming services also lets you build a customized platform with the services you need (sometimes called Services as a Platform [SaaP]). When you use cloud-hosted services, you do not need expertise in operating every service your applications require. This dramatically impacts your ability to change and adds value to your business.

When you are unable to consume services, you should build applications to manage infrastructure. When you do so, the bottleneck for scale no longer depends on how many servers can be managed per operations engineer. Instead, you can approach scaling your infrastructure the same way as scaling your applications. In other words, if you are able to run applications that can scale, you can scale your infrastructure with applications.

The same benefits apply for making infrastructure that is resilient and easy to debug. You can gain insight into your infrastructure by using the same tools you use to manage your business applications.

Cloud native practices can also bridge the gap between traditional engineering roles (a common goal of DevOps). Systems engineers will be able to learn best practices from applications, and application engineers can take ownership of the infrastructure where their applications run.

Cloud native infrastructure is not a solution for every problem, and it is your responsibility to know if it is the right solution for your environment (see Chapter 2). However, its success is evident in the companies that created the practices and the many other companies that have adopted the tools that promote these patterns. See Appendix C for one example.

Before we dive into the solution, we need to understand how these patterns evolved from the problems that created them.

Servers

At the beginning of the internet, web infrastructure got its start with physical servers. Servers are big, noisy, and expensive, and they require a lot of power and people to keep them running. They are cared for extensively and kept running as long as possible. Compared to cloud infrastructure, they are also more difficult to purchase and prepare for an application to run on them.

Once you buy one, it’s yours to keep, for better or worse. Servers fit into the well-established capital expenditure cost of business. The longer you can keep a physical server running, the more value you will get from your money spent. It is always important to do proper capacity planning and make sure you get the best return on investment.

Physical servers are great because they’re powerful and can be configured however you want. They have a relatively low failure rate and are engineered to avoid failures with redundant power supplies, fans, and RAID controllers. They also last a long time. Businesses can squeeze extra value out of hardware they purchase through extended warranties and replacement parts.

However, physical servers lead to waste. Not only are the servers never fully utilized, but they also come with a lot of overhead. It’s difficult to run multiple applications on the same server. Software conflicts, network routing, and user access all become more complicated when a server is maximally utilized with multiple applications.

Hardware virtualization promised to solve some of these problems.

Virtualization

Virtualization emulates a physical server’s hardware in software. A virtual server can be created on demand, is entirely programmable in software, and never wears out so long as you can emulate the hardware.

Using a hypervisor2 increases these benefits because you can run multiple virtual machines (VMs) on a physical server. It also allows applications to be portable because you can move a VM from one physical server to another.

One problem with running your own virtualization platform, however, is that VMs still require hardware to run. Companies still need to have all the people and processes required to run physical servers, but now capacity planning becomes harder because they have to account for VM overhead too. At least, that was the case until the public cloud.

Infrastructure as a Service

Infrastructure as a Service (IaaS) is one of the many offerings of a cloud provider. It provides raw networking, storage, and compute that customers can consume as needed. It also includes support services such as identity and access management (IAM), provisioning, and inventory systems.

IaaS allows companies to get rid of all of their hardware and to rent VMs or physical servers from someone else. This frees up a lot of people resources and gets rid of processes that were needed for purchasing, maintenance, and, in some cases, capacity planning.

IaaS fundamentally changed infrastructure’s relationship with businesses. Instead of being a capital expenditure benefited from over time, it is an operational expense for running your business. Businesses can pay for their infrastructure the same way they pay for electricity and people’s time. With billing based on consumption, the sooner you get rid of infrastructure, the smaller your operational costs will be.

Hosted infrastructure also made consumable HTTP Application Programming Interfaces (APIs) for customers to create and manage infrastructure on demand. Instead of needing a purchase order and waiting for physical items to ship, engineers can make an API call, and a server will be created. The server can be deleted and discarded just as easily.

Running your infrastructure in a cloud does not make your infrastructure cloud native. IaaS still requires infrastructure management. Outside of purchasing and managing physical resources, you can—and many companies do—treat IaaS identically to the traditional infrastructure they used to buy and rack in their own data centers.

Even without “racking and stacking,” there are still plenty of operating systems, monitoring software, and support tools. Automation tools3 have helped reduce the time it takes to have a running application, but oftentimes ingrained processes can get in the way of reaping the full benefit of IaaS.

Platform as a Service

Just as IaaS hides physical servers from VM consumers, platform as a service (PaaS) hides operating systems from applications. Developers write application code and define the application dependencies, and it is the platform’s responsibility to create the necessary infrastructure to run, manage, and expose it. Unlike IaaS, which still requires infrastructure management, in a PaaS the infrastructure is managed by the platform provider.

It turns out, PaaS limitations required developers to write their applications differently to be effectively managed by the platform. Applications had to include features that allowed them to be managed by the platform without access to the underlying operating system. Engineers could no longer rely on SSHing to a server and reading log files on disk. The application’s life cycle and management were now controlled by the PaaS, and engineers and applications needed to adapt.

With these limitations came great benefits. Application development cycles were reduced because engineers did not need to spend time managing infrastructure. Applications that embraced running on a platform were the beginning of what we now call “cloud native applications.” They exploited the platform limitations in their code and in many cases changed how applications are written today.

If you consume all your infrastructure through a PaaS provider, congratulations, you already have many of the benefits of cloud native infrastructure. This includes platforms such as Google App Engine, AWS Lambda, and Azure Cloud Services. Any successful cloud native infrastructure will expose a self-service platform to application engineers to deploy and manage their code.

However, many PaaS platforms are not enough for everything a business needs. They often limit language runtimes, libraries, and features to meet their promise of abstracting away the infrastructure from the application. Public PaaS providers will also limit which services can integrate with the applications and where those applications can run.

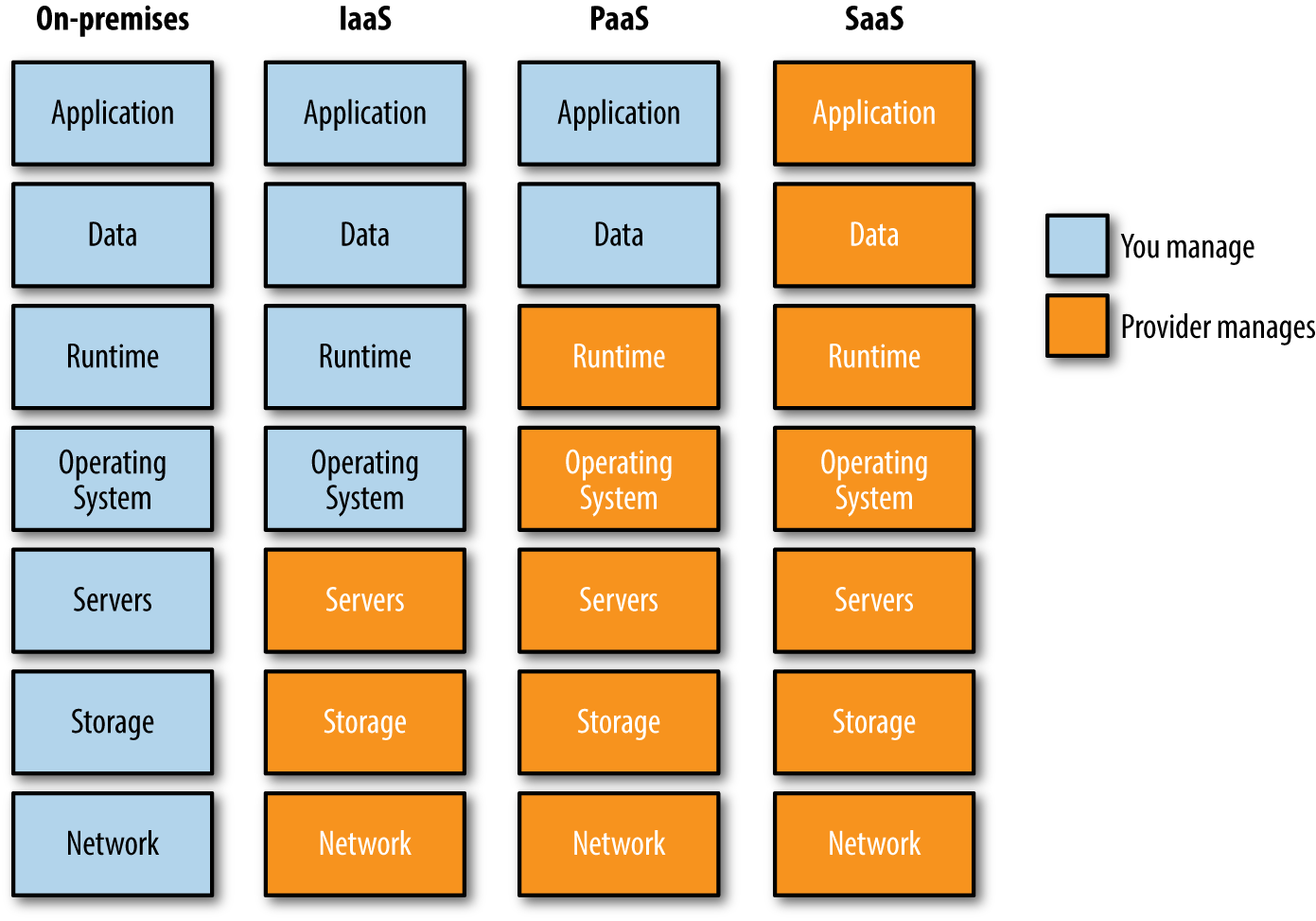

Public platforms trade application flexibility to make infrastructure somebody else’s problem. Figure 1-1 is a visual representation of the components you will need to manage if you run your own data center, create infrastructure in an IaaS, run your applications on a PaaS, or consume applications through software as a service (SaaS). The fewer infrastructure components you are required to run, the better; but running all your applications in a public PaaS provider may not be an option.

Figure 1-1. Infrastructure layers

Cloud Native Infrastructure

“Cloud native” is a loaded term. As much as it has been hijacked by marketing departments, it still can be meaningful for engineering and management. To us, it is the evolution of technology in the world where public cloud providers exist.

Cloud native infrastructure is infrastructure that is hidden behind useful abstractions, controlled by APIs, managed by software, and has the purpose of running applications. Running infrastructure with these traits gives rise to a new pattern for managing that infrastructure in a scalable, efficient way.

Abstractions are useful when they successfully hide complexity for their consumer. They can enable more complex uses of the technology, but they also limit how the technology is used. They apply to low-level technology, such as how TCP abstracts IP, or higher levels, such as how VMs abstract physical servers. Abstractions should always allow the consumer to “move up the stack” and not reimplement the lower layers.

Cloud native infrastructure needs to abstract the underlying IaaS offerings to provide its own abstractions. The new layer is responsible for controlling the IaaS below it as well as exposing its own APIs to be controlled by a consumer.

Infrastructure that is managed by software is a key differentiator in the cloud. Software-controlled infrastructure enables infrastructure to scale, and it also plays a role in resiliency, provisioning, and maintainability. The software needs to be aware of the infrastructure’s abstractions and know how to take an abstract resource and implement it in consumable IaaS components accordingly.

These patterns influence more than just how the infrastructure runs. The types of applications that run on cloud native infrastructure and the kinds of people who work on them are different from those in traditional infrastructure.

If cloud native infrastructure looks a lot like a PaaS offering, how can we know what to watch out for when building our own? Let’s quickly describe some areas that may appear like the solution, but don’t provide all aspects of cloud native infrastructure.

What Is Not Cloud Native Infrastructure?

Cloud native infrastructure is not only running infrastructure on a public cloud. Just because you rent server time from someone else does not make your infrastructure cloud native. The processes to manage IaaS are often no different than running a physical data center, and many companies that have migrated existing infrastructure to the cloud4 have failed to reap the rewards.

Cloud native is not about running applications in containers. When Netflix pioneered cloud native infrastructure, almost all its applications were deployed with virtual-machine images, not containers. The way you package your applications does not mean you will have the scalability and benefits of autonomous systems. Even if your applications are automatically built and deployed with a continuous integration and continuous delivery pipeline, it does not mean you are benefiting from infrastructure that can complement API-driven deployments.

It also doesn’t mean you only run a container orchestrator (e.g., Kubernetes and Mesos). Container orchestrators provide many platform features needed in cloud native infrastructure, but not using the features as intended means your applications are dynamically scheduled to run on a set of servers. This is a very good first step, but there is still work to be done.

Scheduler Versus Orchestrator

The terms “scheduler” and “orchestrator” are often used interchangeably.

In most cases, the orchestrator is responsible for all resource utilization in a cluster (e.g., storage, network, and CPU). The term is typically used to describe products that do many tasks, such as health checks and cloud automation.

Schedulers are a subset of orchestration platforms and are responsible only for picking which processes and services run on each server.

Cloud native is not about microservices or infrastructure as code. Microservices enable faster development cycles on smaller distinct functions, but monolithic applications can have the same features that enable them to be managed effectively by software and can also benefit from cloud native infrastructure.

Infrastructure as code defines and automates your infrastructure in machine-parsible language or domain-specific language (DSL). Traditional tools to apply code to infrastructure include configuration management tools (e.g., Chef and Puppet). These tools help greatly in automating tasks and providing consistency, but they fall short in providing the necessary abstractions to describe infrastructure beyond a single server.

Configuration management tools automate one server at a time and depend on humans to tie together the functionality provided by the servers. This positions humans as a potential bottleneck for infrastructure scale. These tools also don’t automate the extra parts of cloud infrastructure (e.g., storage and network) that are needed to make a complete system.

While configuration management tools provide some abstractions for an operating system’s resources (e.g., package managers), they do not abstract away enough of the underlying OS to easily manage it. If an engineer wanted to manage every package and file on a system, it would be a very painstaking process and unique to every configuration variant. Likewise, configuration management that defines no, or incorrect, resources is only consuming system resources and providing no value.

While configuration management tools can help automate parts of infrastructure, they don’t help manage applications better. We will explore how cloud native infrastructure is different by looking at the processes to deploy, manage, test, and operate infrastructure in later chapters, but first we will look at which applications are successful and when you should use cloud native infrastructure.

Cloud Native Applications

Just as the cloud changed the relationship between business and infrastructure, cloud native applications changed the relationship between applications and infrastructure. We need to see what is different about cloud native compared to traditional applications so we can understand their new relationship with infrastructure.

For the purposes of this book, and to have a shared vocabulary, we need to define what we mean when we say “cloud native application.” Cloud native is not the same thing as a 12-factor application, even though they may share some similar traits. If you’d like more details about how they are different, we recommend reading Beyond the Twelve-Factor App, by Kevin Hoffman (O’Reilly, 2012).

A cloud native application is engineered to run on a platform and is designed for resiliency, agility, operability, and observability. Resiliency embraces failures instead of trying to prevent them; it takes advantage of the dynamic nature of running on a platform. Agility allows for fast deployments and quick iterations. Operability adds control of application life cycles from inside the application instead of relying on external processes and monitors. Observability provides information to answer questions about application state.

Cloud Native Definition

The definition of a cloud native application is still evolving. There are other definitions available from organizations like the CNCF.

Cloud native applications acquire these traits through various methods. It can often depend on where your applications run5 and the processes and culture of the business. The following are common ways to implement the desired characteristics of a cloud native application:

-

Microservices

-

Health reporting

-

Telemetry data

-

Resiliency

-

Declarative, not reactive

Microservices

Applications that are managed and deployed as single entities are often called monoliths. Monoliths have a lot of benefits when applications are initially developed. They are easier to understand and allow you to change major functionality without affecting other services.

As complexity of the application grows, the benefits of monoliths diminish. They become harder to understand, and they lose agility because it is harder for engineers to reason about and make changes to the code.

One of the best ways to fight complexity is to separate clearly defined functionality into smaller services and let each service independently iterate. This increases the application’s agility by allowing portions of it to be changed more easily as needed. Each microservice can be managed by separate teams, written in appropriate languages, and be independently scaled as needed.

So long as each service adheres to strong contracts,6 the application can improve and change quickly. There are of course many other considerations for moving to microservice architecture. Not the least of these is resilient communication, which we address in Appendix A.

We cannot go into all considerations for moving to microservices. Having microservices does not mean you have cloud native infrastructure. If you would like to read more, we suggest Sam Newman’s Building Microservices (O’Reilly, 2015). While microservices are one way to achieve agility with your applications, as we said before, they are not a requirement for cloud native applications.

Health Reporting

Stop reverse engineering applications and start monitoring from the inside.

Kelsey Hightower, Monitorama PDX 2016: healthz

No one knows more about what an application needs to run in a healthy state than the developer. For a long time, infrastructure administrators have tried to figure out what “healthy” means for applications they are responsible for running. Without knowledge of what actually makes an application healthy, their attempts to monitor and alert when applications are unhealthy are often fragile and incomplete.

To increase the operability of cloud native applications, applications should expose a health check. Developers can implement this as a command or process signal that the application can respond to after performing self-checks, or, more commonly, as a web endpoint provided by the application that returns health status via an HTTP code.

Moving health responsibilities into the application makes the application much easier to manage and automate. The application should know if it’s running properly and what it relies on (e.g., access to a database) to provide business value. This means developers will need to work with product managers to define what business function the application serves and to write the tests accordingly.

Examples of applications that provide heath checks include Zookeeper’s ruok command7 and etcd’s HTTP /health endpoint.

Applications have more than just healthy or unhealthy states. They will go through a startup and shutdown process during which they should report their state through their health check. If the application can let the platform know exactly what state it is in, it will be easier for the platform to know how to operate it.

A good example is when the platform needs to know when the application is available to receive traffic. While the application is starting, it cannot properly handle traffic, and it should present itself as not ready. This additional state will prevent the application from being terminated prematurely, because if health checks fail, the platform may assume the application is not healthy and stop or restart it repeatedly.

Application health is just one part of being able to automate application life cycles. In addition to knowing if the application is healthy, you need to know if the application is doing any work. That information comes from telemetry data.

Telemetry Data

Telemetry data is the information necessary for making decisions. It’s true that telemetry data can overlap somewhat with health reporting, but they serve different purposes. Health reporting informs us of application life cycle state, while telemetry data informs us of application business objectives.

The metrics you measure are sometimes called service-level indicators (SLIs) or key performance indicators (KPIs). These are application-specific data that allow you to make sure the performance of applications is within a service-level objective (SLO). If you want more information on these terms and how they relate to your application and business needs, we recommend reading Chapter 4 from Site Reliability Engineering (O’Reilly).

Telemetry and metrics are used to solve questions such as:

-

How many requests per minute does the application receive?

-

Are there any errors?

-

What is the application latency?

-

How long does it take to place an order?

The data is often scraped or pushed to a time series database (e.g., Prometheus or InfluxDB) for aggregation. The only requirement for the telemetry data is that it is formatted for the system that will be gathering the data.

It is probably best to, at minimum, implement the RED method for metrics, which collects rate, errors, and duration from the application.

- Rate

- Errors

- Duration

Telemetry data should be used for alerting rather than health monitoring. In a dynamic, self-healing environment, we care less about individual application instance life cycles and more about overall application SLOs. Health reporting is still important for automated application management, but should not be used to page engineers.

If 1 instance or 50 instances of an application are unhealthy, we may not care to receive an alert, so long as the business need for the application is being met. Metrics let you know if you are meeting your SLOs, how the application is being used, and what “normal” is for your application. Alerting helps you to restore your systems to a known good state.

If it moves, we track it. Sometimes we’ll draw a graph of something that isn’t moving yet, just in case it decides to make a run for it.

Ian Malpass, Measure Anything, Measure Everything

Alerting also shouldn’t be confused with logging. Logging is used for debugging, development, and observing patterns. It exposes the internal functionality of your application. Metrics can sometimes be calculated from logs (e.g., error rate) but requires additional aggregation services (e.g., ElasticSearch) and processing.

Resiliency

Once you have telemetry and monitoring data, you need to make sure your applications are resilient to failure. Resiliency used to be the responsibility of the infrastructure, but cloud native applications need to take on some of that work.

Infrastructure was engineered to resist failure. Hardware used to require multiple hard drives, power supplies, and round-the-clock monitoring and part replacements to keep an application available. With cloud native applications, it is the application’s responsibility to embrace failure instead of avoid it.

In any platform, especially in a cloud, the most important feature above all else is its reliability.

David Rensin, The ARCHITECHT Show: A crash course from Google on engineering for the cloud

Designing resilient applications could be an entire book itself. There are two main aspects to resiliency we will consider with cloud native application: design for failure, and graceful degradation.

Design for failure

The only systems that should never fail are those that keep you alive (e.g., heart implants, and brakes). If your services never go down,8 you are spending too much time engineering them to resist failure and not enough time adding business value. Your SLO determines how much uptime is needed for a service. Any resources you spend to engineer uptime that exceeds the SLO are wasted.

Note

Two values you should measure for every service should be your your mean time between failures (MTBF) and mean time to recovery (MTTR). Monitoring and metrics allow you to detect if you are meeting your SLOs, but the platform where the applications run is key to keeping your MTBF high and your MTTR low.

In any complex system, there will be failures. You can manage some failures in hardware (e.g., RAID and redundant power supplies) and some in infrastructure (e.g., load balancers); but because applications know when they are healthy, they should also try to manage their own failure as best they can.

An application that is designed with expectations of failure will be developed in a more defensive way than one that assumes availability. When failure is inevitable, there will be additional checks, failure modes, and logging built into the application.

It is impossible to know every way an application can fail. Developing with the assumption that anything can, and likely will, fail is a pattern of cloud native applications.

The best state for your application to be in is healthy. The second best state is failed. Everything else is nonbinary and difficult to monitor and troubleshoot. Charity Majors, CEO of Honeycomb, points out in her article “Ops: It’s Everyone’s Job Now” that “distributed systems are never up; they exist in a constant state of partially degraded service. Accept failure, design for resiliency, protect and shrink the critical path.”

Cloud native applications should be adaptable no matter what the failure is. They expect failure, so they adjust when it’s detected.

Some failures cannot and should not be designed into applications (e.g., network partitions and availability zone failures). The platform should autonomously handle failure domains that are not integrated into the applications.

Graceful degradation

Cloud native applications need to have a way to handle excessive load, no matter if it’s the application or a dependent service under load. One way to handle load is to degrade gracefully. The Site Reliability Engineering book describes graceful degradation in applications as offering “responses that are not as accurate as or that contain less data than normal responses, but that are easier to compute” when under excessive load.

Some aspects of shedding application load are handled by infrastructure. Intelligent load balancing and dynamic scaling can help, but at some point your application may be under more load than it can handle. Cloud native applications need to be aware of this inevitability and react accordingly.

The point of graceful degradation is to allow applications to always return an answer to a request. This is true if the application doesn’t have enough local compute resources, as well as if dependent services don’t return information in a timely manner. Services that are dependent on one or many other services should be available to answer requests even if dependent services are not. Returning partial answers, or answers with old information from a local cache, are possible solutions when services are degraded.

While graceful degradation and failure handling should both be implemented in the application, there are multiple layers of the platform that should help. If microservices are adopted, then the network infrastructure becomes a critical component that needs to take an active role in providing application resiliency. For more information on building a resilient network layer, please see Appendix A.

Declarative, Not Reactive

Because cloud native applications are designed to run in a cloud environment, they interact with infrastructure and supporting applications differently than traditional applications do. In a cloud native application, the way to communicate with anything is through the network. Many times network communication is done through RESTful HTTP calls, but it can also be implemented via other interfaces such as remote procedure calls (RPC).

Traditional applications would automate tasks through message queues, files written on shared storage, or local scripts that triggered shell commands. The communication method reacted to an event that happened (e.g., if the user clicks submit, run the submit script) and often required information that existed on the same physical or virtual server.

Reactive communication in traditional applications is often an attempt to build resiliency. If the application wrote a file on disk or into a message queue and then the application died, the result of the message or file could still be completed.

This is not to say technologies like message queues should not be used, but rather that they cannot be relied on for the only layer of resiliency in a dynamic and constantly failing system. Fundamentally, the communication between applications should change in a cloud native environment—not only because there are other methods to build communication resiliency (see Appendix A), but also because it is often more work to replicate traditional communication methods in the cloud.

When applications can trust the resiliency of the communication, they should stop reacting and start declaring. Declarative communication trusts that the network will deliver the message. It also trusts that the application will return a success or an error. This isn’t to say having applications watch for change is not important. Kubernetes’ controllers do exactly that to the API server. However, once change is found, they declare a new state and trust the API server and kubelets to do the necessary thing.

The declarative communication model turns out to be more robust for many reasons. Most importantly, it standardizes a communication model and it moves the functional implementation of how something gets to a desired state away from the application to a remote API or service endpoint. This helps simplify applications and allows them to behave more predictably with each other.

How Do Cloud Native Applications Impact Infrastructure?

Hopefully, you can tell that cloud native applications are different than traditional applications. Cloud native applications do not benefit from running directly on IaaS or being tightly coupled to a server’s operating system. They expect to be run in a dynamic environment with mostly autonomous systems.

Cloud native infrastructure creates a platform on top of IaaS that provides autonomous application management. The platform is built on top of dynamically created infrastructure to abstract away individual servers and promote dynamic resource allocation scheduling.

Note

Automation is not the same thing as autonomous. Automation allows humans to have a bigger impact on the actions they take.

Cloud native is about autonomous systems that do not require humans to make decisions. It still uses automation, but only after deciding the action needed. Only when the system cannot automatically determine the right thing to do should it notify a human.

Applications with these characteristics need a platform that can pragmatically monitor, gather metrics, and then react when failures occur. Cloud native applications do not rely on humans to set up ping checks or create syslog rules. They require self-service resources abstracted away from selecting a base operating system or package manager, and they rely on service discovery and robust network communication to provide a feature-rich experience.

Conclusion

The infrastructure required to run cloud native applications is different than traditional applications. Many responsibilities that infrastructure used to handle have moved into the applications.

Cloud native applications simplify their code complexity by decomposing into smaller services. These services provide monitoring, metrics, and resiliency built directly into the application. New tooling is required to automate the management of service proliferation and life cycle management.

The infrastructure is now responsible for holistic resource management, dynamic orchestration, service discovery, and much more. It needs to provide a platform where services don’t rely on individual components, but rather on APIs and autonomous systems. Chapter 2 discusses cloud native infrastructure features in more detail.

1 Some of these things may be considered applications on their own; in this book we will consider applications to be the software that generates revenue to sustain a business.

2 Type 1 hypervisors run on hardware servers with the sole purpose of running virtual machines.

3 Also called “infrastructure as code.”

4 Called “lift and shift.”

5 Running an application in a cloud is valid whether that cloud is hosted by a public vendor or run on-premises.

6 Versioning APIs is a key aspect to maintaining service contracts. See https://cloud.google.com/appengine/docs/standard/go/designing-microservice-api for more information.

7 Just because an application provides a health check doesn’t mean the application is healthy. One example of this is Zookeeper’s ruok command to check the health of the cluster. While the application will return imok if the health command can be run, it doesn’t perform any tests for application health beyond responding to the request.

8 As in a service outage, not a component or instance failure.

Get Cloud Native Infrastructure now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.