Users have a hard enough time reading what’s displayed on a screen. A long flow of text, unbroken by title, subtitles, and other headers, crosses the eyes and numbs the mind, not to mention the fact that it makes it nearly impossible to scan the text for a specific topic.

You should always break a flow of text into several smaller sections within one or more headings (like this book). There are six levels of HTML/XHTML headings that you can use to structure a text flow into a more readable, more manageable document. And, as we discuss in Chapter 5 and Chapter 8, there are a variety of graphical and text-style tricks that help divide your document and make its contents more accessible as well as more readable to users.

The six heading

tags, written as <h1>,

<h2>, <h3>,

<h4>, <h5>, and

<h6>, indicate the highest

(<h1>) to lowest

(<h6>) precedence that a heading may have in

the document.

The enclosed text within a heading typically is rendered by the browser uniquely, depending upon the display technology available to it. The browser may choose to center, embolden, enlarge, italicize, underline, or change the color of headings to make each stand out within the document. And in order to thwart the most tedious writers, often users themselves can alter how a browser renders the different headings.

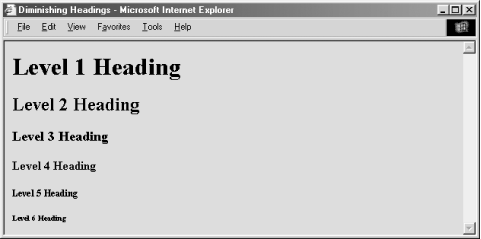

Fortunately, in practice most browsers use a diminishing character

point size for the sequence of headers, so that

<h1> text is quite large and

<h6> text is quite minuscule (see Figure 4-3, for example).

By tradition, authors have come to use <h1>

headers for document titles, <h2> headers

for section titles, and so on, often matching the way many of us were

taught to outline our work with heads, subheads, and sub-subheads.

Finally, don’t forget to include the appropriate heading end tags in your document. The browser won’t insert them automatically for you, and omitting the ending tag for a heading can have disastrous consequences for your document.

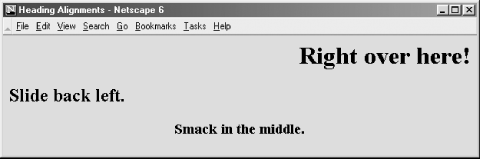

The

default heading alignment for most browsers is

left. As with the <div>

and <p> tags, the align

attribute can change the alignment to left,

center, right, or

justify. Figure 4-4 shows these

alternative alignments as rendered from the following source:

<h1 align=right>Right over here!</h1> <h2 align=left>Slide back left.</h2> <h3 align=center>Smack in the middle.</h3>

The justify

value for

align is not yet supported by any browser, and

don’t hold your breath. The align

attribute is deprecated in HTML 4 and XHTML, in deference to style

sheet-based controls.

The dir attribute lets you advise the browser

which direction the text within that paragraph should be displayed

in, and lang

lets

you specify the language used within the heading. [Section 3.6.1.1] [Section 3.6.1.2]

Use the id

attribute to create a label for the heading that can later be to used

to unambiguously reference that heading in a hyperlink target, for

automated searches, as a style-sheet selector, and with a host of

other applications. Section 4.1.1.4 Use the optional

title

attribute and quote-enclosed string value to provide a descriptive

phrase for the heading. [Section 4.1.1.4]

Use the style

attribute with the heading tags to create an inline style for the

headings’ contents. The class

attribute lets you label the heading with a name that refers to a

predefined class declared in some document-level or externally

defined style sheet. [Section 8.1.1] [Section 8.3]

Each user-initiated event that may happen in and around a heading is recognized by the browser if it conforms to the HTML or XHTML standard. With the respective “on” attribute and value, you may react to that event by displaying a user dialog box or activating some multimedia event. [Section 12.3.3]

It’s

often good form to repeat your document’s title in

the first heading tag, since the title you specify in the

<head> of your document

doesn’t appear in the user’s main

display window. The following HTML segment is a good example of

repeating the document’s title in the header and in

the body of the document:

<html> <head> <title>Kumquat Farming in North America</title> </head> <body> <h3>Kumquat Farming in North America</h3> <p> Perhaps one of the most enticing of all fruits is the...

Typically, the browser places the <title>

text along the top of the main display. It may also place the title

elsewhere in the document window and use it to create bookmarks or

favorites entries, all of which vaguely are somewhere on the

user’s desktop. The level-three title heading in

this example, on the other hand, will always appear at the very

beginning of the document display. It serves as a visible title to

the document, regardless of how the browser handles the

<title> tag’s contents.

And, unlike the <title> text, the heading

title gets printed at the beginning of the first page should the user

elect to print the document, because it is part of the main text.

[<title>]

In our example, we chose to use a level-three heading

(<h3>) whose rendered font typically is just

a bit larger than the regular document text. Levels one and two are

larger still and often a bit overbearing. You should choose a level

of heading that you find useful and attractive and use that level

consistently throughout your documents. Too big and it overwhelms the

display window. Too small and it’s easily missed

visually.

Once you have established the top-level heading for your document, use additional headings at the same or lower levels throughout to add structure and “scanability” to the document. If you use a level-three heading for the document title, for example, break your document into subsections using level-four headings. If you have the urge to subdivide your text further, consider using a level-two heading for the title, level three for the section dividers, and level four for the subsections.

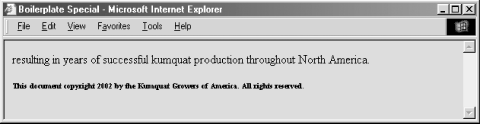

For

most graphical browsers, the fonts used to display

<h1>, <h2>, and

<h3> headers are larger,

<h4> is the same, and

<h5> and <h6> are

smaller than the regular text size. Authors typically use the latter

two sizes for boilerplate text, like a disclaimer or a copyright

notice. It’s become quite popular to use the smaller

text in tables of contents or home pages that display a

site’s contents. Experiment with

<h5> and <h6> to

get the effect you want. See how a typical browser renders the

copyright reference in the following sample XHTML segment (see Figure 4-5):

resulting in years of successful kumquat production throughout North America. </p> <h6>This document copyright 2002 by the Kumquat Growers of America. All rights reserved.</h6> </body> </html>

A heading may contain any element

allowed in text, including conventional text, hyperlinks

(<a>), images

(<img>), line breaks

(<br>), font embellishments

(<b>, <i>,

<tt>, <u>,

<strike>, <big>,

<small>, <sup>,

<sub>, and <font>),

and content-based styles (<acronym>,

<cite>, <code>,

<dfn>, <em>,

<kbd>, <samp>,

<strong>, and

<var>). In practice, however, font or style

changes may not take effect within a heading, since the heading

itself prescribes a font change within the browser.

At one time early on, there was widespread abuse of the heading tags as a way to change the font of entire sections of a document. Technically, paragraphs, lists, and other block elements are not allowed within a heading and may be mistaken by the browser to indicate the implied end of the heading. In practice, most browsers apply the style of the heading to all contained paragraphs. We discourage this practice, since it is not only a violation of HTML and XHTML standards but usually is ugly to look at. Imagine if your local paper printed all the copy in headline type!

Large sections of heading text defeat the purpose of the tag. If you really want to change the font or type sizes in your document, use the standard cascading style definitions. See Chapter 8 for details.

We strongly recommend that you carefully test your pages with more

than one browser and at several different resolutions. As you might

expect, your <h6> text may be readable at

320 x 480 resolution but disappear on a 600 x

800 display.

Formally, the HTML and XHTML standards allow headings only within body content. In practice, most browsers recognize headings almost anywhere, formatting the rendered text to fit within the current element. In all cases, the occurrence of a heading signifies the end of any preceding paragraph or other text element, so you can’t use the heading tags to change font sizes in the same line. Rather, use cascading style definitions to achieve those acute display effects. [Section 8.1.1]

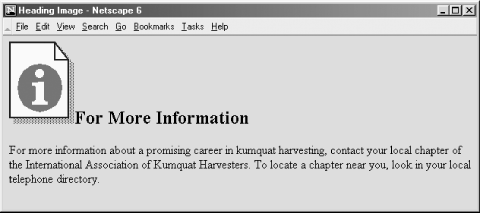

It is possible to insert one or more images within your headings, from small bullets or icons to full-sized logos. Combining a consistent set of headings with corresponding icons across a family of documents is not only visually attractive but also an effective way of aiding users’ perusal of your document collection. [<img>]

Adding an image to a heading is easy. For example, the following text puts an “information” icon inside the “For More Information” heading, as you can see in Figure 4-6:

<h2> <img src="info.gif"> For More Information</h2>

In general, images within headings look best at the beginning of the heading, aligned with the bottom or middle of the heading text.

Get HTML & XHTML: The Definitive Guide, 5th Edition now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.