Ownership and permissions are central to security. It’s important to get them right, even when you’re the only user, because odd things can happen if you don’t. For the files that users create and use daily, these things usually work without much thought (although it’s still useful to know the concepts). For system administration, matters are not so easy. Assign the wrong ownership or permission, and you might get into a frustrating bind like being unable to read your mail. In general, the message:

Permission denied

means that someone has assigned an ownership or permission that restricts access more than you want.

Permissions refer to the ways in which someone can use a file. There are three such permissions under Unix:

When each file is created, the system assigns some default permissions that work most of the time. For instance, it gives you both read and write permission, but most of the world has only read permission. If you have a reason to be paranoid, you can set things up so that other people have no permissions at all.

Additionally, most utilities know how to assign permissions. For instance, when the compiler creates an executable program, it automatically assigns executable permission.

There are times when defaults don’t work, though. For instance, if you create a shell script or Perl program, you’ll have to assign executable permission yourself so that you can run it. We’ll show how to do that later in this section, after we get through the basic concepts.

Permissions have different meanings for a directory:

Read permission means you can list the contents of that directory.

Write permission means you can add or remove files in that directory.

Execute permission means you can list information about the files in that directory.

Don’t worry about the difference between read and execute permission for directories; basically, they go together. Assign both or neither.

Note that, if you allow people to add files to a directory, you are also letting them remove files. The two privileges go together when you assign write permission. However, there is a way you can let users share a directory and keep them from deleting each other’s files. See Section 7.3.3 in Chapter 7.

There are more files on Unix systems than the plain files and directories we’ve talked about so far. These are special files (devices), sockets, symbolic links, and so forth — each type observing its own rules regarding permissions. But you don’t need to know the details on each type.

Now, who gets these permissions? To allow people to work together, Unix has three levels of permission: owner, group, and other. The “other” level covers everybody who has access to the system and who isn’t the owner or a member of the group.

The idea behind having groups is to give a set of users, like a team of programmers, access to a file. For instance, a programmer creating source code may reserve write permission to herself, but allow members of her group to have read access through a group permission. As for “other,” it might have no permission at all so that people outside the team can’t snoop around. (You think your source code is that good?)

Each file has an owner and a group. The owner is generally the user who created the file. Each user also belongs to a default group, and that group is assigned to every file the user creates. You can create many groups, though, and assign each user to multiple groups. By changing the group assigned to a file, you can give access to any collection of people you want. We’ll discuss groups more when we get to Section 5.7.4 in Chapter 5.

Now we have all the elements of our security system: three permissions (read, write, execute) and three levels (user, group, other). Let’s look at some typical files and see what permissions are assigned.

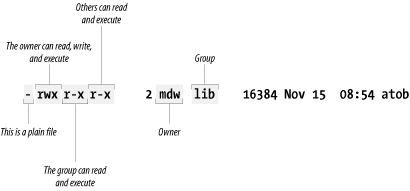

Figure 4-2 shows a typical executable program. We

generated this output by executing ls with the

-l option.

Two useful facts stand right out: the owner of the file is an author

of this book and your faithful guide, mdw, while

the group is lib (perhaps a group created for

programmers working on libraries). But the key information about

permissions is encrypted in the set of letters on the left side of

the display.

The first character is a hyphen, indicating a plain file. The next

three bits apply to the owner; as we would expect,

mdw has all three permissions. The next three bits

apply to members of the group: they can read the file (not too useful

for a binary file) and execute it, but they can’t

write to it because the field that should contain a

w contains a hyphen instead. And the last three

bits apply to “other”; they have

the same permissions in this case as the group.

Here is another example: if you ask for a long listing of a C source file, it would look something like this:

$ ls -l

-rw-rw-r-- 1 kalle kalle 12577 Apr 30 13:13 simc.cThe listing shows that the owner has read and write

(rw) privileges, and so does the group. Everyone

else on the system has only read privileges.

Now suppose we compile the file to create an executable program. The

file simc is created by the

gcc compiler:

$gcc -osimc simc.c$ls -ltotal 36 -rwxrwxr-x 1 kalle kalle 19365 Apr 30 13:14 simc -rw-rw-r-- 1 kalle kalle 12577 Apr 30 13:13 simc.c

In addition to the read and write bits, gcc has

set the executable (x) bit for owner, group, and

other on the executable file. This is the appropriate thing to do so

that the file can be run:

$ ./simc

(output here)One more example — a typical directory:

drwxr-xr-x 2 mdw lib 512 Jul 17 18:23 perl

The leftmost bit is now a d to show that this is a

directory. The executable bits are back because you want people to

see the contents of the directory.

Files can be in some obscure states that aren’t covered here; see the ls manual page for gory details. But now it’s time to see how you can change ownership and permissions.

Get Running Linux, Fourth Edition now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.