In its day, the concept of overlapping windows on the screen was brilliant, innovative, and extremely effective. (Apple borrowed this idea—well, bought it in a stock swap—from a research lab called Xerox PARC.) In that era before digital cameras, MP3 files, and the Web, managing windows was easy this way; after all, you had only about three of them.

These days, however, managing all the open windows in all the open programs can be like herding cats. Off you go, burrowing through the microscopic pop-up menus of your Dock, trying to find the window you want. And heaven help you if you need to duck back to the desktop—to find a newly downloaded file, for example, or to eject a disk. You’ll have to fight your way through 50,000 other windows on your way to the bottom of the “deck.”

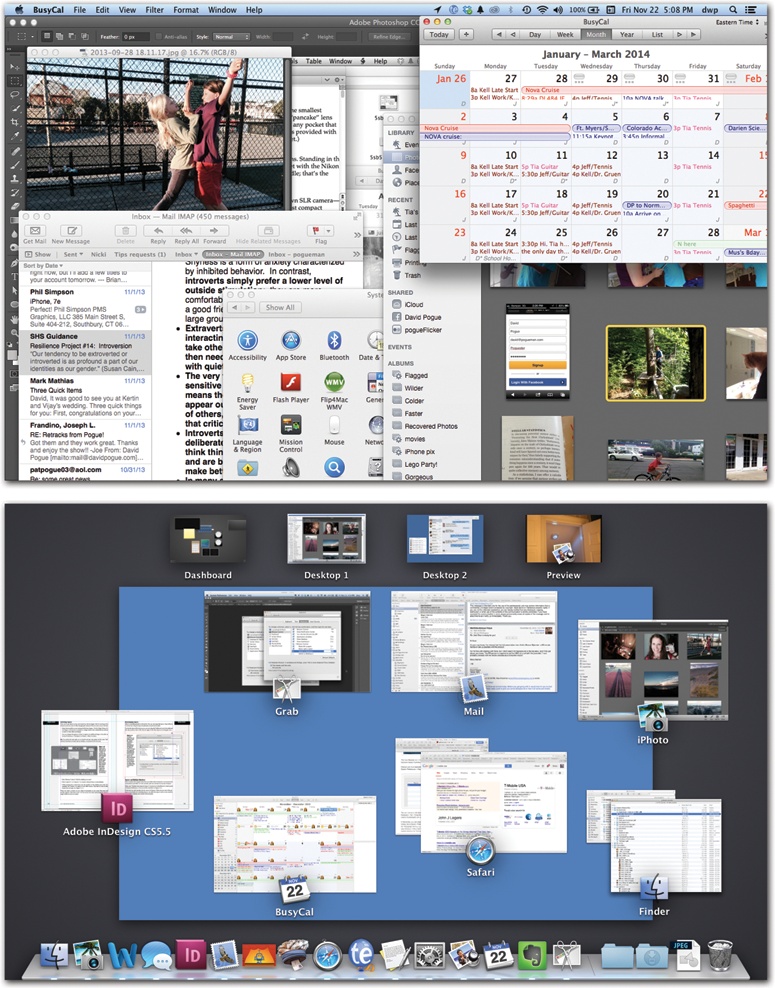

Mission Control tackles this problem in a fresh way. The concept is delicious: With one mouse click, keystroke, or finger gesture, you shrink all windows in all programs to a size that fits on the screen (Figure 4-8), like index cards on a bulletin board, clumped by open program. Now you feel like an air-traffic controller, with all your screens arrayed before you. You click the window or program you want, and you’re there. It’s fast, efficient, animated, and a lot of fun.

Now, if you’ve ever used earlier versions of OS X, you may remember three other window-management features: Exposé, which also served to shrink windows so you could find them; Spaces, which provided virtual side-by-side monitors; and Dashboard, which presented a gaggle of tiny, single-purpose apps on a single screen.

Mission Control combines all three of those features—Exposé, Spaces, and Dashboard—into one.

Mission Control is a program, just like any other. So you can open it with a click on its Dock icon, from Launchpad, from the Applications folder, and so on.

But it’s really meant to be opened quickly, fluidly, naturally, whenever the mood seizes you—with a gesture. On the trackpad, that’s a swipe upward with three fingers. (On the Magic Mouse, it’s a double-tap with two fingers—taps, not clicks.)

Note

You can change this gesture so that it requires four fingers, if you like, in System Preferences→Trackpad (or Mouse)→More Gestures→Mission Control. Use the pop-up menu.

Or you can press the dedicated ![]() key (formerly the Exposé key), if you have one, on the top row of your keyboard. Substitute the F9 key if you don’t.

key (formerly the Exposé key), if you have one, on the top row of your keyboard. Substitute the F9 key if you don’t.

And even that’s just the beginning of the ways you can open Mission Control; read on.

Note

To exit Mission Control without clicking any of your windows or virtual screens, swipe down with three fingers. Or tap the Esc key.

Figure 4-8. Top: Quick! Where’s the Finder in all this mess? Bottom: With a four-finger upward swipe on the trackpad, you can open Mission Control and spot that window, shrunken but not overlapped. Each program’s thumbnail cluster offers an icon and a label to help you identify it. These aren’t static snapshots of the windows at the moment you Mission Controlled them. They’re live, still-updating windows, as you’ll discover if one of them contains a QuickTime movie or a Web page that’s still loading.

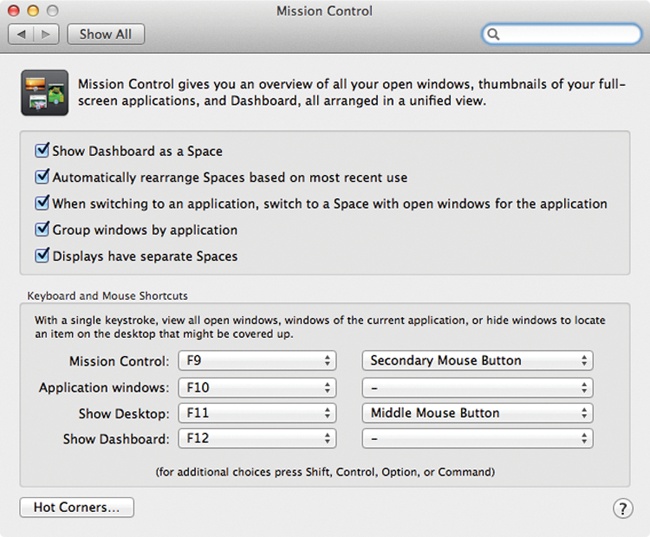

You can reassign the Mission Control functions to a huge range of other keys, with or without modifiers like Shift, Control, and Option. To view your options, choose ![]() →System Preferences and then click the Mission Control icon.

→System Preferences and then click the Mission Control icon.

Here you’ll find four pop-up menus. The first, Mission Control, lets you specify how you want to open Mission Control. The other three—“Application windows,” “Show Desktop,” and “Show Dashboard”—correspond to the three functions of the older Exposé and Dashboard features, described later in this chapter.

Within each pop-up menu, for example, you’ll discover that all your F-keys—F1, F2, F3, and so on—are available as triggers. If, while the pop-up menu is open, you press one or more of your modifier keys (Shift, Option, Control, or ⌘), all these F-key choices change to reflect the key you’re pressing; now the pop-up menu says Shift-F1, Shift-F2, Shift-F3, and so on. That’s how you can make Shift-F1 trigger Mission Control, for example.

These pop-up menus also contain choices like Left Shift, which refers to the Shift key on the left side of your keyboard. That is, instead of pressing F9 to open Mission Control, you could simply tap the Shift key.

Note

This is only an example. Repeat: This is only an example. Actually using the Shift key to open Mission Control is a terrible, terrible idea, as you’ll quickly discover the next time you try to type a capital letter. This would work only for hunt-and-peck typists who never use the Shift key on one side.

If you have a laptop, you’ll also find out that you can tap the Fn key alone for Mission Control—and this time, it’s a great choice, because Fn otherwise has very little direction in life.

If your mouse has more than one button, you see a second column of pop-up menus in System Preferences (Figure 4-9). Each pop-up menu offers choices like Right Mouse Button and Middle Mouse Button. Use these pop-up menus to assign Mission Control (or Exposé or Dashboard) to the various clickers on your mouse: right-click to hide all windows, middle-click to reveal the desktop, and so on.

Note, by the way, that on a laptop, the wording isn’t “right mouse button”—it’s “secondary mouse button.” Which means “right-click.” Which means that on a laptop, you can set it up so that a “right-click” trackpad gesture triggers one of these functions. See Right-Clicking and Shortcut Menus for all the different ways you can trigger a right-click.

If you click Hot Corners, you see a little map of your screen, including all four corners. Using the little pop-up menus, you can assign a window-management feature to each corner; for example, if you choose Mission Control from the first pop-up menu, then when your pointer hits the upper-left corner of the screen, you’ll open Mission Control. (Launchpad is an option here, too.)

Depending on the size of your screen, this option can feel awkward at first. But if you’ve run out of keystrokes that aren’t assigned to other functions, be glad that Apple offers you this alternative.

Figure 4-9. You can trigger Mission Control in any of five ways: by clicking its icon, with a finger gesture, by twitching your cursor into a certain corner of the screen (Hot Corners), by pressing a key (bottom half of this box), or by clicking the extra buttons on a multibutton mouse, including Apple’s Mighty Mouse. Of course, there’s nothing to stop you from setting up all of these ways, so you can press or swipe in some situations and twitch or click in others.

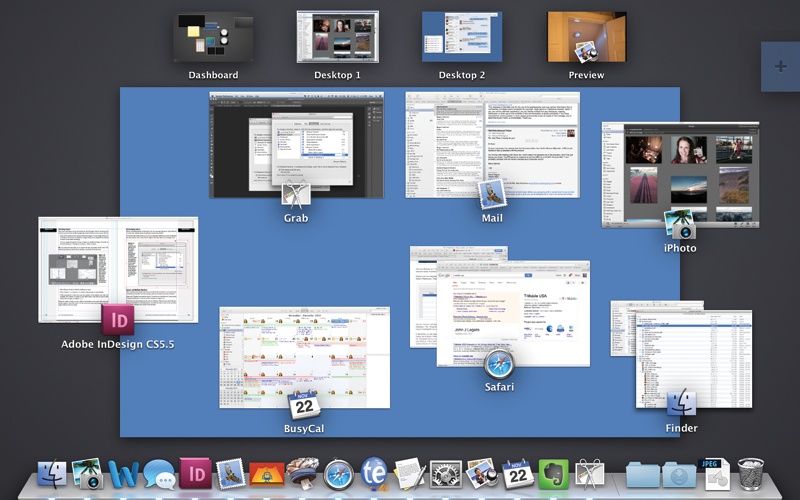

Once you open Mission Control, you see two major elements: your Spaces (virtual screens) at the top, and the actual window thumbnails below that.

You can click anything here to jump to it: Jump to a different Space (desktop) by clicking its thumbnail, switch to a different program by clicking its icon, or click one of the window miniatures.

Tip

Try holding down the Shift key as you do it. You’ll enjoy watching all your windows shift around with OS X’s patented slow-motion animation, which can be quite a sight.

Or, if you decide to abandon ship and return to whatever you were doing, swipe down with three fingers on the trackpad (two on the Magic Mouse), or press the Esc key.

The trouble with miniaturized windows is that, well, they’re miniaturized. The more windows you have open, the smaller they are, and the harder it is to see what’s in them.

If you need a little help identifying a window miniature, you have three options:

Point to the cluster of windows in one app and do a two-finger swipe up on the trackpad. OS X helpfully spreads the window thumbnails out and enlarges them a little bit, so it’s easier to tell them apart and click the one you want.

Point to a window thumbnail without clicking. OS X puts a colored border on it to show that it’s highlighted; now press the space bar. That, of course, is the Quick Look keystroke, and it works here, too. It magnifies the window you’re pointing to, making it full size—big enough for you to read its contents and identify it.

Press ⌘-~. That keystroke takes you into one-app Exposé, described later in this chapter.

Mission Control’s other star feature, Spaces, gives you up to 16 full-size monitors. Ordinarily, of course, attaching so many screens to a single computer would be a massively expensive proposition, not to mention detrimental to your living space and personal relationships.

Fortunately, Spaces monitors are virtual. They exist only in the Mac’s little head. You see only one at a time; you switch using Mission Control or a gesture.

But just because the Spaces screens are simulated doesn’t mean they’re not useful. You can dedicate each one to a different program or kind of program. Screen 1 might contain your email and chat windows, arranged just the way you like them. Screen 2 can hold Photoshop, with an open document and the palettes carefully arrayed. On Screen 3: your Web browser in Full Screen mode.

You can also have the same program running on multiple screens—but with different documents or projects open on each one.

These desktops are also essential to OS X’s full-screen apps feature, because each full-screen app gets its own Spaces desktop.

Mission Control starts you off with two Spaces (or “desktops,” as they’re labeled). One of them shows the Dashboard, described later in this chapter; the other shows your regular Mac world. If you’ve clicked the ![]() button in an app to make it full screen, it fills an additional desktop unto itself.

button in an app to make it full screen, it fills an additional desktop unto itself.

To create another desktop, enter Mission Control. You can now proceed in either of two ways:

The long way. Point to the upper-right corner of the screen, or just press the Option key; a big

button slides into view (Figure 4-10). Click it to create a new mini desktop in the top row.

button slides into view (Figure 4-10). Click it to create a new mini desktop in the top row.Now it’s time to park some windows onto the new desktop. Either drag a window thumbnail onto the blank desktop—or, to move all of one program’s windows there, drag the application icon. All the windows go along for the ride.

The short way. Drag one window thumbnail into a blank spot at the upper-right corner of the screen—or, to move all of one program’s windows there, drag the application icon. Again, all the windows go along for the ride.

Tip

There are two ways to move a window to a different Space without opening Mission Control first. First, you can drag a window (using its title bar as a handle) all the way to the edge of the screen. Stay there with the mouse button still down. After about a second, you’ll see the adjacent screen slide into view; you’ve just moved the window.

Second, switch to the new Space. Hold your mouse down on the app’s icon; from the shortcut menu, choose Options→Assign To→This Desktop. The Mac whisks that app’s windows from whatever other screen they’re on to this screen.

Once you’ve got Spaces set up and turned on, the fun begins. Start by moving to the virtual screen you want; it’s like changing the channel. Here are some ways to do that:

Swipe horizontally on your trackpad with three fingers. (On the Magic Mouse, it’s two fingers.) If you have a trackpad or a Magic Mouse, this is definitely the method to learn; it’s fast, fluid, and happy.

You can change this gesture so that it requires an additional finger, if you like, in System Preferences→Trackpad (or Mouse)→More Gestures.

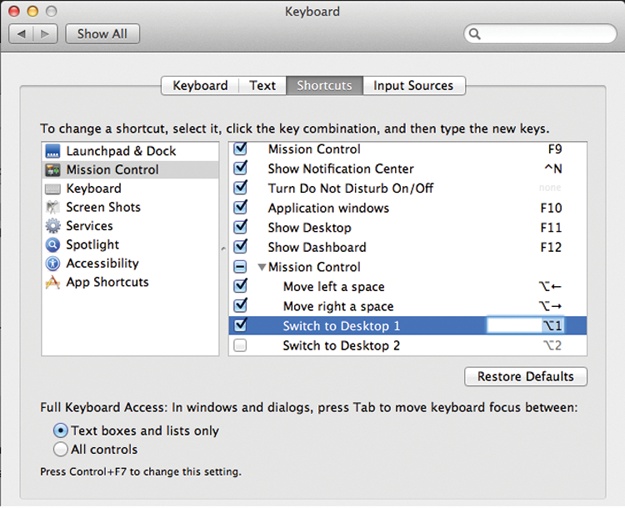

Press Control-

or Control-

or Control- to rotate to the previous or next desktop.

to rotate to the previous or next desktop.While pressing the Control key, type the number of the desktop you want. For example, hit Control-3 to jump to your third screen. (You have to turn on this feature first, though. See Figure 4-11.)

Figure 4-11. To control Spaces from the keyboard, open ![]() →System Preferences→Keyboard. Click Keyboard Shortcuts and then Mission Control. As shown here, Apple has preassigned keyboard shortcuts to your various Spaces—but they’re not turned on yet. Turn on the checkboxes for the shortcuts you want. (You can change those shortcuts here, too.)

→System Preferences→Keyboard. Click Keyboard Shortcuts and then Mission Control. As shown here, Apple has preassigned keyboard shortcuts to your various Spaces—but they’re not turned on yet. Turn on the checkboxes for the shortcuts you want. (You can change those shortcuts here, too.)

When you make a switch, you see a flash of animation as one screen flies away and another appears. Now that you’re “on” the screen you want, open programs and arrange windows onto it as usual.

Tip

What if you’re using Spaces and you want to drag something from one screen (like a photo in iPhoto) into a window that’s on a different screen (like an outgoing email message)?

Two ways; take your pick. First, you can start dragging whatever it is—and then, in mid-drag, press the keystroke for Mission Control (usually Fn-F9); complete the drag directly onto the other Space, and even into the relevant window in that Space.

Another approach: Start dragging. With the mouse button still down, press ⌘-Tab to open the application switcher. Continue the drag onto the icon of the receiving program, and still keep the mouse button down. OS X switches to the appropriate virtual screen automatically.

Here’s something handy in Mavericks: You can rearrange the Spaces. Open Mission Control, then drag the Space thumbnails around horizontally.

You can even drag the Dashboard out of its traditional left-side position. Put it off to the right of the other Spaces, for all Apple cares.

Here’s another favor Apple’s done for you in Mavericks: If you have a second monitor connected to your Mac (or even several), each one can have its own set of Spaces.

Make sure “Displays have separate Spaces” is turned on in the Mission Control panel of System Preferences. (You can see this checkbox in Figure 4-0.)

From now on, each monitor has its own set of Spaces. When you use one of the gestures or keystrokes for switching Spaces, you affect the Spaces on only one monitor: the one that contains your cursor at the moment.

Unless you intervene, OS X uses your main desktop’s background picture for all additional Spaces.

Coolly enough, though, you can set a different wallpaper photo (desktop background) to each Space. You might find it easier to get your bearings that way. When you restart the computer, the Mac will remember not just which Spaces you had open and what was on them, but also what pictures lay behind them.

You can go about assigning desktop pictures in two ways. First, switch to the Space whose picture you want to change. Then:

Open System Preferences→Desktop & Screen Saver→Desktop.

Right-click (or two-finger click) a blank spot on the existing desktop background. From the shortcut menu, choose Change Desktop Background.

Note

In both cases, you may have to move the System Preferences window onto your current Space. You can do that by popping into Mission Control.

Either way, you wind up in the Preferences panel for choosing desktop wallpaper. Click the backdrop you want for this screen. Then switch to the next Space and repeat.

To delete a desktop, enter Mission Control. Point to one of the screen thumbnails without clicking until a ![]() appears in its corner; click it. The desktop disappears, and whatever windows were on it get shoved onto Desktop #1, your main desktop.

appears in its corner; click it. The desktop disappears, and whatever windows were on it get shoved onto Desktop #1, your main desktop.

Tip

If you don’t have the 1½ seconds to wait for the ![]() to appear, then press Option as you point. The Close button appears instantly.

to appear, then press Option as you point. The Close button appears instantly.

By the way, this trick doesn’t work for apps running in Full Screen mode. You can’t get rid of their desktops unless you first switch to them and get out of Full Screen mode.

Get Switching to the Mac: The Missing Manual, Mavericks Edition now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.