Chapter 1. System Overload

If you can smile when things go wrong, you have someone in mind to blame.

It’s not enough to rage against the lie. You’ve got to replace it with the truth.

Blaming People Only Works for So Long

Watching missed business opportunities is always painful. When products fall flat or sales slow down despite best efforts, it’s excruciating to experience the loss of market value. And most of us can guess what comes next: the blame game. Someone must have made the wrong decision, failed to do the right thing, or both. “If only we’d had the right people on the bus, we would have succeeded,” is what we say. The mental betting pools begin on who will wind up getting tossed under that very same bus.

Most often, there’s some good reason for blaming people. After all, mistakes were made. “Any fool could have seen that our supplier couldn’t ramp up production that fast.” “Engineering missed their committed date. Simple as that.” Or “Listen, they’ve walked before, and they’ve chewed gum before. All they had to do was walk and chew gum at the same time!” Well, maybe. Who is at fault is not simply an objective question; it is often a political necessity. So we play “he said, she said,” pick a scapegoat for the failure, and move on. But is this useful? That is, will blaming people help any of our businesses to be successful the next time?

People aren’t the core reason why strategies fail. Of course they are part of the dynamic, but we often look to blame people as if that’s the whole story. If only it were that simple. When failures happen, I have seen that there are persistent, telltale patterns. As I visit Company A in the morning, Company B in the afternoon, and Company C later that same day, day after day for 10 years, I see that the failures are not simply isolated human missteps that can be avoided in the future by replacing one or two individuals. Instead, the issues are subtle variations of systemic problems. Some problems are dominant in one set of companies, and others are dominant in other firms, but the same few crop up over and over. This is great news, because in the failures we can study the systemic issues, understand them, and create a New How to go forward.

Three situations illustrate the systemic problems. All are byproducts of the Air Sandwich we covered in the introduction, where the top of the organization issues orders at the 80,000-foot level and lobs them down to the folks at the 20,000-foot level, without the benefit of feedback, questions, or even a reality check from below. As long as we’re eating Air Sandwiches, we lack the meaty “how” to do an effective job of setting direction and achieving the kind of results we need.

The Three Systemic Patterns

The first situation involves limited participation, the second is about the focus on speed, and the third relates to unresolved questions.

“Tunnel Vision”

Quick, smart, and hard working, Sue was passed over for promotion after promotion, despite good reviews. While personally frustrated at the lack of advancement, she didn’t walk away like so many others would have. She wanted to work with these people and this product set. She didn’t just like the company; she loved it. So, she kept aiming to do even better and crack the secret code. One day, she finally got the insight on why she was passed over for the most senior echelon of leadership. Her boss’s boss shared, “You get involved and drive the things you are specifically chartered to solve, but you don’t jump into stuff outside your domain.” Sue was a great leader within her own discipline, but was not viewed as a company leader.

Now, we could say that Sue just wasn’t that good. We could say it’s an isolated incident involving one person and her individual situation. But of course that’s not the whole story. Sue’s story highlights a pattern of limited participation and holding back that pervaded the company. The company kept bringing in outsiders as the next echelon of leaders rather than promoting from inside. I knew of other mid-level leaders at this firm who were getting similar feedback from different managers. Each leader shared with me why they behaved as they did, and it came down to this: they hesitated to move beyond their specific assignments, out of fear of treading on others’ toes. You see, this firm’s culture valued “getting along.” The systemic problem was that the culture norm constrained each individual to stay within unspoken, invisible lines of behavior. “Working together to solve the problem” was ranked lower than “getting along.” The essential environment for supportive collaborative actions and behaviors was not yet in place.

Remarkably, the executive, Sue, was able to treat her insightful conversation as a springboard to change how the company worked. She used it to set the stage for stepping outside her own domain of expertise and engage with colleagues to drive increased collaboration across boundaries, while the senior execs saw the broader issue and changed the company culture so it was safe for Sue and others to act.

Why does an organization need to drive collaborative actions? Why do people need to step outside their own domains if the business is to thrive? It comes down to this: speed to market happens through cross-silo collaboration. That means companies must work across boundaries and silos to create new things and build greater speed for the company as a whole. The more complex the organization, the more cross-silo collaboration is needed. When members of the organization keep to their isolated sandbox, it leaves holes in the larger tapestry. So firms must seek to avoid the pattern of discouraging productive cross-discipline contribution.

“Ahead of Yourself”

The second costly pattern involves a focus on the doing without shared thinking. Ian, a general manager chartered to grow “the next big thing” for his division, was entrepreneurial and gung-ho. Working with him and a small group of people in the division, my company had identified a brand-new market where buyers had a “latent need”: a deep source of pain they would pay money to solve, but that no offering could solve today. The idea, the competitive landscape, and the size of that market opportunity ($2 billion) were well vetted. The board of the company gave the green light to actively pursue this new market. So far, so good.

That’s when things got off track, and perhaps you’ll see a bit of your own organization in this next part. With “the big idea” approved, Ian brought together his broader management team and all the extended members of the organization responsible for execution. He shared the results of the board discussion with all the “doers”: people from marketing, engineering, delivery, and so on. He finished the update, took a few questions, and then moved on to the next steps. With thinly veiled impatience, he emphasized, “Let’s get going!” One person, dialed in via conference call, raised the key question: “Get going how?” Unseen by the questioner, the look on the GM’s face left no doubt of his low regard for the person. You probably know the look. Intentional or not, it says, “I get it, so why don’t you? What are you, s-l-o-w?” Others present, not wanting to be seen as obstructionist, bit their tongues and got focused on “let’s get going.”

And so it went. Ian effectively said, “Charge up that hill!” (Figure 1-1) and everyone attempted to do so. The team spent six months trying desperately to make the new market materialize, but got nowhere. People exhausted themselves trying to make it happen, but time and again, something was always amiss, and the execution failed. Ian made the mistake of assuming that what was obvious to him was also obvious to everyone else, even people who hadn’t spent close to a year investigating the new opportunity. By going straight to execution without sorting out dependencies and risks, and explaining why certain things needed to happen, Ian failed to align his team. So everyone raced off at top speed with no coordination, looking like a tribute to the movie Keystone Kops. You already know where this story ends, right? Failure. After six months of zero progress, formerly committed teammates began taking other jobs. Ian was moved to another role. That particular “hill” was never seized, and a lot of business opportunity was lost. Everyone—team members, Ian, execs—was frustrated, though not all in the same way.

Of course, wanting to move fast and get a-going toward a plum of an opportunity is not a bad thing! Speed absolutely matters. But there are devils in those details that enable people to go fast, in the right direction, together! When people don’t understand what is really needed, they can’t make key decisions that align with all the other players. Try as they might, they each end up going in slightly different directions. Ian’s 80,000-foot take was that what needed to happen next was “clear,” and he wanted people to get into gear and go, go, go. Ian did not just forget to ask for thinking—he squashed the very notion. Strategic thinking, including things like understanding all that would need to change, deliberating options, making tough choices between those options, and nailing down who owns what responsibilities, does not happen in spite of a process. It needs to be driven by the process. Ultimately, it is effective collaborative thinking that completes the “how” of strategy and drives the speed of execution. You can align people by the very way that strategy is created. The thinking and “why” of what matters gets encoded into the organizational ethos, the building blocks of every future action. That’s when you can outpace the competition. To fix this systemic issue, you have to change the very way strategy gets created.

“It’s Not My Job”

The third systemic pattern of failure involves decision making near the source of the problem. A successful firm I was working with, which I’ll call Livery, was expanding from a software tools company (making software programs that people use) to a platform company (making software that other developers use to create their own programs). To accomplish this big strategic shift, a lot of things at the company needed to change, from the kinds of products they built to how they built them. Their goals required getting many external software developers involved and committed to this new platform, which meant that they no longer had 100% control of their own destiny. On many levels, it would take a new approach to doing business for them to succeed.

There was no one owner of this shift; it involved everyone at Livery, so everyone had to own a part of the larger strategy. When a significant problem arose, no single party could solve it, because it affected five different leaders and their divisional responsibilities. One leader opted to research the issue, to find its root cause and make recommendations for how to move forward. So far, so good: there was a problem, and someone took responsibility for it. But when this leader came back with recommendations to share with his peers, do you know what he heard?

Rather than a meaty discussion on how to apply the recommendations, what he got instead was pushback. “We’ve known that for some time,” “how will we know for sure” that the recommended solutions would work, and “we’ve tried that before” were the gist of the conversation. The responses guaranteed that many questions would go unresolved. Zero progress was made. All agreed they needed to solve the problem, but the comfortable focus on things-already-known cut short the rather messy but necessary forward-looking conversation. The five leaders were struggling with learning about the unknown and how to drive change. Each leader had well-defined individual goals, which did not add up to success. The gaps in between their roles were not owned and thus compromised the business outcome. Because all of them owned it, no one owned it. They were the right people with the perspective and judgment to make the decision, but they were not comfortable with it. They did not want to bear the risk of the decision, and had other work nagging them for attention. And so, despite clear evidence of a problem and some consensus that the problem was in their neighborhood, the leaders did nothing.

There was a side effect as well. When the leaders show that they’re reluctant to tackle change, other people in the organization who start out eager to initiate change and drive new solutions get stuck. “Why bother? It’s above my pay grade.” They go back to their defined job title-related roles until someone tells them it’s time to do something different on behalf of the company. Everyone is exasperated at the lack of progress. The leaders can’t see how their subtle insistence on certainty and clear, definitive answers for a new business problem actually stall progress. That risk-averse demand for certainty undermines the collaborative problem solving and tough choices needed to enable business success.

Why does it matter who in an organization handles unresolved questions? Many companies would just let festering issues bubble up to the top echelon of the leadership, but that slows company progress. And besides, does the very top of a complex organization really have the right context to make most calls? Organizations benefit when the people nearest the issue figure out how to solve it. Luckily, when the CEO drove a new way of working, Livery was able to figure out new ways the organization could make decisions closer to the point of action. Some people left because it was so different than their command-and-control way of working, but the overall sense of responsibility within the organization grew, and with it their ability to compete in the marketplace.

The Telltale Signs

Although it would be easy to look at these stories as isolated situational flaws, they are really common systemic issues companies face. They are evidence of how many firms are systemically set up to fail at strategy creation. While many people say they value collaboration, their people, processes, and organizational systems are not set up to support it. Each story highlights a particular element that was missing from the strategy creation process, namely:

The collaborative actions and attitudes that encourage people to step up and shape the organization’s future together.

A way to work through the energy-consuming and often untidy process of shared strategy creation that reaches beyond the big idea, while still arriving at an end destination in a timely manner.

The organizational ability to share ownership, do shared problem solving, and make decisions nearest the source of the problem, enabling the whole organization to go fast and stay aligned.

To transform how companies set direction and achieve results, it’s important to understand and tune (or in some cases, reinvent) the way we enable people to create, communicate, make decisions, work collaboratively, and take action. To support straightforward examination, it helps to translate these stories into specific warning signs that we can look for in our organizations. There are always telltale signs of the three systemic ways strategy fails, and there are key lessons in those signs.

These telltale signs are clues to your organization’s larger view on strategy and the strategy creation process. It’s these signs that point to surefire failure (Figure 1-2). When cooperation, co-creation, and a careful exploration of ideas are discouraged, an organization fails to tap the talents, knowledge, and experience of its people.

Consider whether you recognize any of the three signs in Table 1-1 from your own experience.

|

PARTICIPATION AND OWNERSHIP | |

|

Signs |

Lesson for collaborative strategy |

|

|

|

ORGANIZATIONAL WISDOM AND READINESS | |

|

Signs |

Lesson for collaborative strategy |

|

|

|

|

|

DISTRIBUTED DECISION MAKING | |

|

Signs |

Lesson for collaborative strategy |

|

|

We all need to avoid focusing on templates or framework outlines and instead focus on getting people to think about what matters and why. Although the people creating those strategy templates are doing good work, they often don’t realize that they are not encouraging thinking. Even with well-defined outputs and things moving quickly, the business can go south because the right debates, discussions, and decisions have not yet happened. In other words, without collaboration, strategy can appear to be done well but in reality it lacks the substance to create better business outcomes.

Strategies created in these environments are incomplete and at high risk of failure during implementation and execution. The Air Sandwich gets perpetuated. Let’s look at how to set up a successful strategy creation system.

Strategy in the Organizational System

For a strategy creation process to engage people and still work optimally, a host of organizational elements need to come together. We aim to create an environment that supports people working together in the dynamic tension that enables generating excellent ideas, challenging underlying assumptions, vetting those ideas, sharing ownership, gaining a deep understanding, and establishing accountability for success. What follows will paint the full picture of how organizations can come together to form strategy.

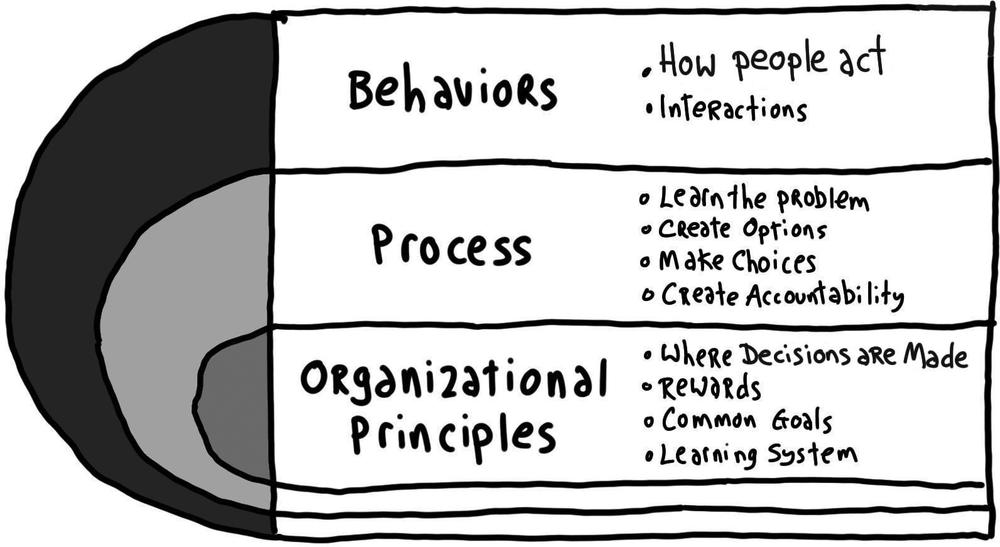

First, even bright, talented, and motivated people cannot jointly create effective strategies—ones that people can implement to produce great results—until the fundamental enablers of collaboration are in place. If responsibility-sharing, decision-making, or idea-generation protocols do not enable a co-creative and collaborative approach, individuals can’t overcome the obstacles to success. The fundamental organizational enablers for collaborative strategy fall into three areas (Figure 1-3):

- Individual behaviors and attitudes

How do people act individually and within groups in the company?

- Strategic process

Is there a structure or method that helps people learn the problem, create options, make tough choices, and create accountability while setting direction?

- Organizational principles

Where are decisions made within the company, what is rewarded, how are goals set, and how are disputes resolved so learning happens?

Of course, all three parts of the individual behaviors, strategic process, and organizational principles are tied to the organizational system. By establishing a set of shared attitudes, values, goals, and practices for your organization or team, you’ll establish a system of collaborative, productive work. Let’s explore each of these elements and how they ultimately come together to help you and your organization establish effective strategy and reach new results.

Individual Behaviors and Attitudes in Collaborative Strategy

As we all know, simply telling people what needs to be done is rarely enough to produce action. Yet that’s exactly what many organizations often do in the strategy process. Creating excellent strategy depends on collaboration throughout the organization.

This book will explain in detail a new holistic approach for aligning people to a direction by involving them in fully defining the “what” (the idea) and the “how” (developing options for how to deliver on the idea) and helping them all to understand the “why” (the reasons why something matters). When the what/how/why come together, then people come to own it. They believe in what they are doing.

They know how to make subtle decisions that, in aggregate, make the difference between success and failure. They know how to react a few weeks down the road when some change threatens to knock things askew. We call this new approach the New How.

This has specific implications. For collaborative strategy creation to work, we need to have a way for many people, regardless of title or rank, to participate in setting direction. And we also need their ideas to be valued and their contributions respected. Good strategies require great new ideas that can come from anyone and are often not a product of any single individual. Getting at the valuable ideas that are embedded in your team requires sharing ownership of success within the organization. The act of recognizing ideas based on their merit, not just based on who proposed them, gives some credit and recognition to the individuals or teams behind these ideas. Doing this well moves the focus to the ideas and shared ownership. As will become clear, it is important to be able to build up, tear down, and reconstruct ideas. It’s best if individuals don’t get too tightly bound to their ideas, or they may perceive criticisms of the ideas as personal attacks. Also, we want the full team to be comfortable adding to the ideas. So we seek shared ownership of ideas, and ranking of ideas based on their merit. We call this dynamic a “meritocracy of ideas.”

Quite often, this means that people don’t need to have fully formed recommendations before arriving at the table, but instead bring their thinking ability. Thinking happens “in the moment,” and so often the individual nuggets and partial ideas are not airtight. Rather than criticizing and discarding incomplete ideas, leaders will build upon the useful pieces and encourage the shaping of options through an iterative process. The sources of individual ideas can see how their contributions were carried forward, which allows them to buy into the resulting strategy.

It sounds good to have a meritocracy of ideas, but it also raises the stakes for all the people involved. It means that people in the organization share a responsibility to play an active role, where they take personal responsibility for what gets created. When people are invited to participate, they need to be fully present with their points of view and willing to engage in setting direction. That means putting aside egos and politics and to stop attending meetings as observers, passively awaiting direction. Rather, the expectation on each of us is to show up as full participants in discovery and creation. It is easier said than done.

Later, when the decision is made, each of us knows we’ve been heard and feels as though the decision is, in a real sense, our decision. When that’s true, we support the call that ultimately gets made.

Whether people choose to fully engage is deeply influenced by the behaviors and attitudes of the company’s leaders. So we’ll define what behaviors and attitudes are needed to enable productive collaboration.

But people’s behaviors are not enough to enable a collaborative environment. We also need to set up work processes that enable people to come together.

Process for Collaborative Strategy

The strategy gap represented by the organizational Air Sandwich will not be filled with more presentations from above. PowerPoint slides are just another form of air in the sandwich. What’s missing from the Air Sandwich isn’t repetition of high-level ideas, it’s practical understanding. Getting more people involved in the process leads to two benefits. First, it increases the diversity of perspectives, which means more potential ideas that win and more potential pitfalls avoided early. And second, it means decisions aren’t simply directives from above. By having two-way communication about the strategy as it is formed, follow-on decisions can be made faster and better because the people making those decisions understand the intent behind the strategy, and why X must be done and Y must not be done, and how to choose between W and Z when those decisions arise. This lets management push the decision-making process closer to execution, supporting much faster action and helping to ensure that the cascade of decisions align with one another.

To accomplish this, however, we need to go slow to go fast. We need to involve the right people, do the necessary drill-down, and flesh out the feasibility details so it will work. Unlike what Ian believed was right, people need to create the “how” of strategy. But the process cannot take forever. We need to limit it. We need a process that supports participatory investigation, yet converges in a practical amount of time and generates a concise and specific set of actions. Our strategy creation process, and the mindset of the people driving it, must meet several key criteria to ensure both understanding and quick closure:

The process and mindset must ensure a shared understanding of the current context. By surfacing both the explicit and the underlying context, all team members can have the same view, and the process will drive alignment and preempt divergence during execution.

The process must identify right-sized problems. Big problems must be deconstructed so they can be tackled by your organization. Some organizations try to take on the biggest problems all at the same time—what I call eating an elephant in one sitting (Figure 1-4). These organizations don’t really know their limits, and they don’t know what’s involved in their tasks. They take on tasks that are too large, and consequently they fail.

The process must help translate the inherent tensions of a problem into constructive, creative energy. When debate and brainstorming are welcomed, people can both contribute and process new data, insights, and perspectives. Without debate, issues will not be surfaced, and people will find it difficult to aim toward the right target. Organizations that squash debate typically “jump the gun” by getting started on problem solving without first fully understanding the root cause of a problem.

The process should include mechanisms to identify and resolve conflict. Organizations often struggle with collaboration when the time comes to converge on a unified strategy. Many people are involved, and every idea in the pool seems to be someone’s favorite. Teams tend to overinvest in trying to keep every idea alive.[4] For collaboration to work, the process must provide a way to cull the best ideas from all the options. We need to know how to spray weed-killer on some ideas and put fertilizer on others.

With an effective shared process in place, organizations can finally do the necessary discovery, debate, and elimination of ideas so they can lead the march toward progress and, in the end, success. Included in the New How is a specific yet flexible and convergent process framework.

But no process can take hold if the organization doesn’t have rules and principles in place to ensure that people cooperate and align with one another. That’s a crucial part of a collaborative strategy process.

Organizational Principles for Collaborative Strategy

The notion of harnessing the untapped talent, ideas, and insights of your people and their ideas isn’t new.

But collaboration in action is rare because there is trickiness to it. It requires a mindset and a well-tuned process, and they need to mesh. It’s very hard to add collaboration to an existing organization. There is a kind of quandary, the business strategy version of a Catch-22. If you’re struggling, you’re too busy to sort out how to switch to a new approach. If you’re ahead of the pack, then why change? But occasionally a large and successful organization will not follow that faulty logic, like Tiger Woods choosing to optimize his swing. John Chambers has told us that Cisco, the dominant firm in networking, is turning the battleship by institutionalizing collaboration.[5]

Organizational rules of engagement can present pernicious problems for doing strategy collaboratively. This is because, in part, these rules are about invisible structures and abstract systems that are embedded in the fabric of the organization. The ownership of these rules feels anonymous. If these rules create motivations at odds with collaboration, then nascent efforts to encourage teamwork can be doomed. And so these rules must be examined closely. The New How identifies four principles for defining rules that enable organizations to collaborate effectively: they involve driving decisions locally, setting up incentives that reward common success, defining common goals, and making learning a key function of the organization.

One thing that helps organizations to collaborate is to view strategy creation less as a rigid turn-the-crank effort and more as a pathway to discovery. This highlights the “how” of strategy, what I refer to simply as “strategizing.” Strategizing organizations view strategy as both a noun and a verb. The team members are constantly alert for ways to enhance success, knowing that some ideas will get integrated into execution quickly, and others will be pocketed until the time is right.

Organizations collaborate best when the rewards are based more on organizational success and less on individual accomplishment. Similarly, collaboration works when the results are measured, progress is tracked, and people stay in touch with what is going on. Without tracking, you get poor coordination, weak feedback, and weak accountability. Commitment and momentum will fade. You’ll see that the organizational principles provide the glue that connects the people and processes into an organization-wide ability to win.

Naming the Systemic Issues Lets Us Fix Them

In light of all these ideas, can you look back at a strategy creation process you have been involved in—perhaps one where it didn’t work out well—and see systemic patterns of weakness? Perhaps you had an experience, like the one I shared in this book’s introduction, where you had an inkling that things weren’t quite right. There are always early warning signs, but they can be hard to make sense of without a frame of reference. And even if you see them, addressing them is tricky unless the organization is oriented toward taking a systemic view of strategy creation.

We know now that people are not solely to blame. People are just one of the core elements that influence the dynamic of strategy creation, yet they’re typically the prime targets when a strategy goes belly up. Blaming strategy breakdowns on individuals gives management the sense that they have fixed something. But when strategy is created in an impaired system, swapping out people doesn’t fix much.

Good strategy creation depends on both a good system and good people. If you have a talented team and assemble the right systemic elements—individual behaviors and attitudes, processes, and organizational principles—you have the makings of a powerful organization for creating strategy. The rest of this book is organized into three parts aimed at addressing the systemic components.

Part I describes how people need to “be” in the system, both as individuals and as leaders. How we engage with one another matters a great deal, because people generate the ideas and make the decisions that determine what value we create together. How we behave toward one another is inseparable from how we work together.

Part II focuses on the methodology for doing collaborative strategy. Setting direction is an art and a practice. We need to know when and how to open up the spigot of ideas, and when to close the spigot and accomplish something. Collaborative planning and decision making has a bad rap, somewhat deserved, for never “getting there.” By introducing a solid yet flexible process framework, you can be both collaborative and fast. Part II also includes the chapter on the MurderBoarding process, which is the basis of the strategy selection method. Readers interested in narrowing options may read Chapter 6 on its own.

Part III takes us up a level to think about the rules of engagement that organizations can put in place to foster a culture of collaboration and successful strategy outcomes. Changing organizational culture requires more than just bold moves and big announcements. How do you get whole groups of people to alter the way they think, work, and act? To help a new culture stick, you need a small number of big changes, and thousands of supporting small acts. This section covers the principles for incorporating collaboration into your company’s dynamic.

Let’s get started with Part I.

Get The New How now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.