Design patterns for orchestrating collaborative groups

It’s only when you enable people to “do things” together that the real power of online social networks is unleashed.

Pattern network (source: Pexels)

Pattern network (source: Pexels)

I still remember the moment I saw a big piece of the future. It was mid-1999, and Dave Winer called to say there was something I had to see.

He showed me a web page. I don’t remember what the page contained except for one button. It said, “edit_this_page”—and, for me, nothing was ever the same again.

I clicked the button. Up popped a text box containing plain text and a small amount of HTML, the code that tells a browser how to display a given page. Inside the box I saw the words that had been on the page. I made a small change, clicked another button that said, “Save this page” and voilà, the page was saved with the changes….

Dave was a leader in a move that brought back to life the promise, too long unmet, that Tim Berners-Lee, inventor of the Web, had wanted from the start. Berners-Lee envisioned a read/write Web. But what had emerged in the 1990s was an essentially read-only Web on which you needed an account with an ISP to host your web site, special tools, and/or HTML expertise to create a decent site.

What Dave and the other early blog pioneers did was a breakthrough. They said the Web needed to be writeable, not just readable, and they were determined to make doing so dead simple.

Thus, the read/write Web was truly born again.

DAN GILLMOR, DAVE WINER: A TOAST, http://bit.ly/1gnjETA

Collaboration

The first thing I ever posted on the Web was person: a story (http://ezone.org/no/bird.html). The next thing I produced and posted was collaborative: a magazine (http://ezone.org). This was 1994. We knew we wanted to engage newcomers more fully than the traditional letters to the editor, and many of the letters (and email messages) we received at the time were submissions. People wanted to work with us and we wanted to work with them, and they came from all over the world. We managed for four years with no system in place besides a series of personal understandings, but any form of collaboration requires some form of orchestration, and our ad hoc approach didn’t scale.

In the earliest days of online social-networking applications (think SixDegrees and Friendster), there eventually came the “so what” problem: you could make an account, register your name, find people, connect to them, and then… what? There was no there there. You might be able to form groups and discuss things, but of course you could already do that through a lot of other interfaces (such as email lists and Usenet, for Pete’s sake), even if they weren’t explicitly noted as social.

No, it’s only when you begin enabling people to “do things” together that the real power of online social networks kicks in.

Today, it’s possible to orchestrate collaborative groups through a series of time-tested, well-proven design patterns. These patterns provide people with a shared space, give them a way to invite others, provide the means for managing tasks, employ version control, and look after people’s rights.

Wiki projects, such as the omnipresent Wikipedia; open source software development using tools such as Sourceforge, Collabnet, and Github; Yahoo! Groups; and charismatically driven groups of people such as Ze Frank’s (http://zefrank.com) fanbase, which you can see in Figure 1-1, have all demonstrated the power that can be unleashed when you give people interfaces for working together on their shared concerns.

Manage Project

What

When people get together and form groups, they often discover a shared desire to accomplish something tangible or complex, frequently something with a real-world (offline) impact (see Figure 1-2).

This pattern is also known as a “Workspace” pattern.

Use when

Use this pattern when you have enabled group formation and wish to host and support group project activities. If you don’t have the bandwidth (literally or figuratively) to support this, consider supporting third-party services.

How

-

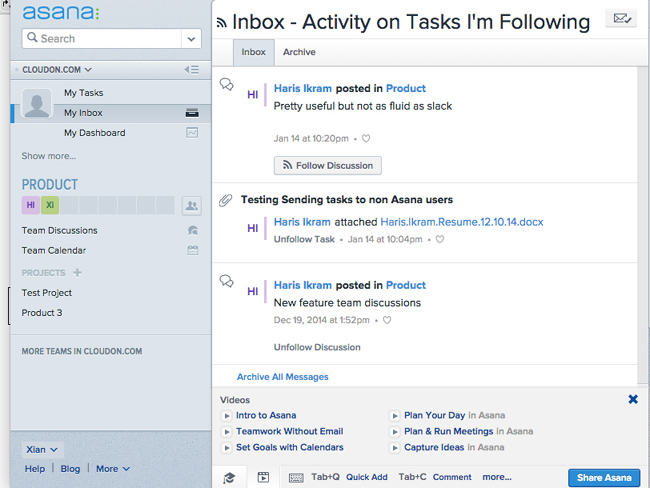

Support your members’ ability to orchestrate projects by coordinating goals, tasks, and deadlines among multiple participants with varying degrees of commitment and availability.

-

Provide a workspace for connecting all the facets of the project (people, tasks, dates, collateral) and, if possible, offer a summarized dashboard view linking to more detailed inventories by facet. This makes asynchronous communication possible across disconnected geographies.

-

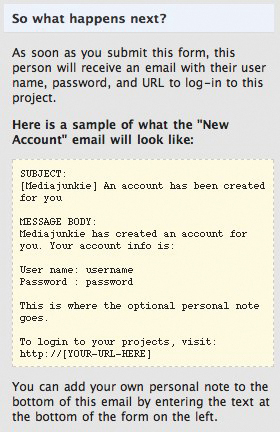

Provide a mechanism for the creator of the project or a participant to bring in collaborators with Send Invitation, and possibly to assign varying rights by individual or group, as shown in Figure 1-3.

Figure 1-3. With Basecamp, you can add an entire company (team) to your project or invite individuals by adding them to an existing company. -

Support task management with the ability to assign tasks, accept tasks, and distribute processes among multiple participants by breaking them down into individual tasks. Optionally support the ability to declare that one task is dependent on another and possibly calculate the critical path to the end goal.

-

Provide a calendar on which deadline and milestone dates can be scheduled and then verified.

-

Offer the ability to send messages to project participants, as well as reminders and notifications.

-

Provide a means for collaborative editing of documents or source code, including version control (Figure 1-4).

Figure 1-4. At GitHub, I can make my own clone of the YUI 3.0 codebase, fork it, and then have it merged back into the main trunk. -

Include a way for project participants to make and keep track of decisions.

-

Optionally provide an interface for project blogging or statuscasting so that project participants can report on their progress and anyone can see at a glance what has been happening lately on the project. Or, provide a timeline view on the dashboard to roll up all recent events in chronological order.

Why

Giving your community members the tools to work together or comanage their own efforts increases the utility of your service and the culture of the social environment. However, your users can often do this effectively via email and phone and perhaps a filesharing system. Do you have anything more to offer? Do you need to?

As seen on

Asana

Confluence

Basecamp (http://basecamphq.com)

Bugzilla (http://bugzilla.org)

Github (http://github.com)

Groove (http://office.microsoft.com/groove/)

SharePoint (http://www.microsoft.com/sharepoint/)

Traction (http://tractionsoftware.com)

Voting

What

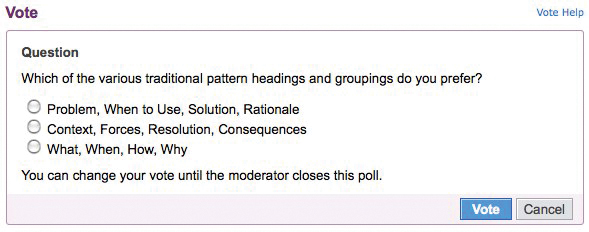

To make decisions, the members or stakeholders of a group need a way to give their opinions, and project leaders need to know which options have the most support from the participating community, as illustrated in Figure 1-5.

This pattern is also known as “Polls” or “Surveys.”

Use when

Use this pattern to collect the opinion of a group of people around a topic (with facets).

This pattern works best when groups are large enough that only a core subgroup is doing most of the collaboration, to provide a voice to the less fully engaged members of the group.

Voting can be in an enterprise or workgroup context. It also can integrate equally well in a consumer context, in which a group of people freely associating with one another need ways to discern their preferences and make collective decisions.

How

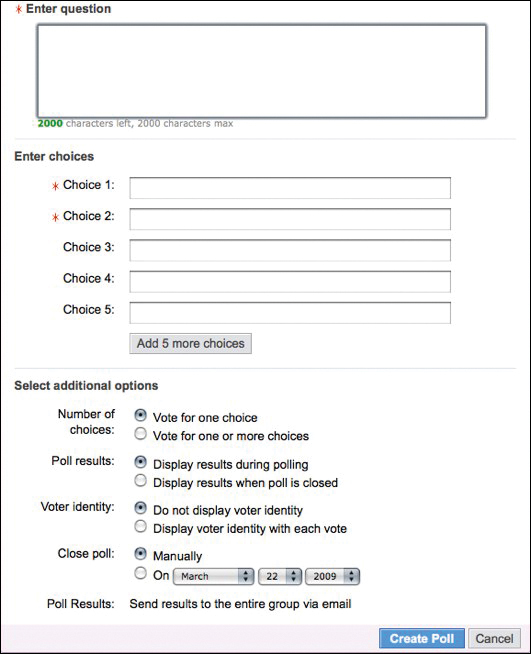

Provide a form by which a group moderator or participant can suggest a question or topic to be voted on, and then facilitate a series of possible votes (anything from “yes” or “no” to a multiple-choice option).

Optionally, provide configuration choices governing such issues as how long the voting will remain open, whether users can change their vote, whether votes are anonymous or open, whether a person is restricted to vote for a single choice or can vote for more than one, or whether a ranking of choices is preferred, as demonstrated in Figure 1-6.

Why

Voting and surveys provide a means of soliciting feedback about specific questions from a wider participating community.

Note that it’s possible for some users to game voting systems, especially if no fixed identity is required or authenticated before voting; voting can provide perverse incentives in much the way that a leaderboard can; and there are many competing voting algorithms out there, each with its own pros and cons.

As seen on

Evite (http://evite.com)

SurveyMonkey (http://surveymonkey.com)

Yahoo! Groups (http://groups.yahoo.com)

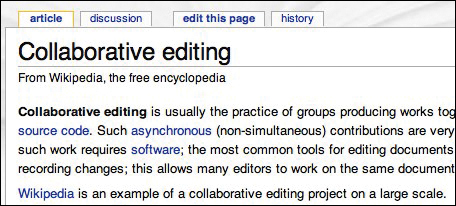

Collaborative Editing

What

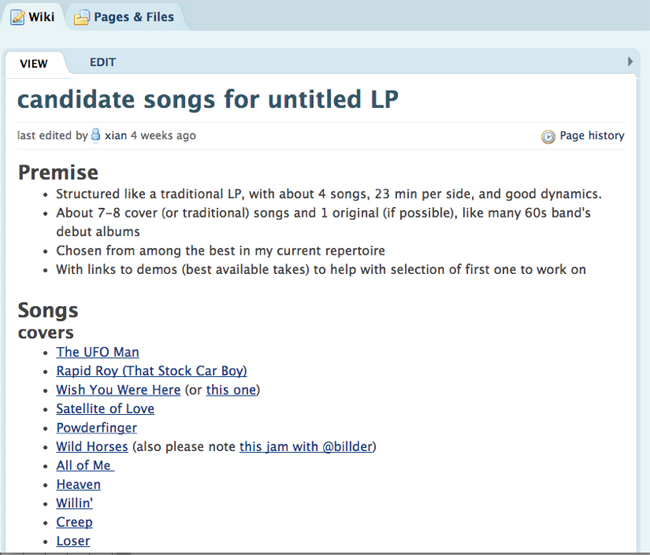

People like to be able to work together on documents, encyclopedias, and software codebases, as depicted in Figure 1-7.

Use when

Use this pattern when you want your members to be able to work together to curate their collective wisdom or document their shared knowledge.

How

-

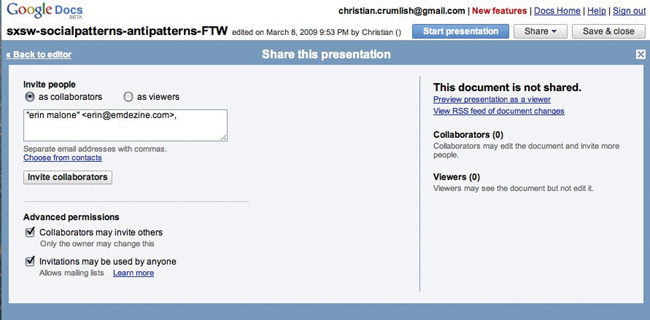

Provide a repository for hosting documents with version control. Give users a way to bring in additional collaborators with an invitation to participate, as in Figure 1-8.

Figure 1-8. You can use the “Invite to Participate” pattern to invite collaborators to work together on a document. -

Provide an Edit This Page link (see Edit This Page) directly on the document to be edited, or give users the means to upload incrementally updated versions of a stored document.

-

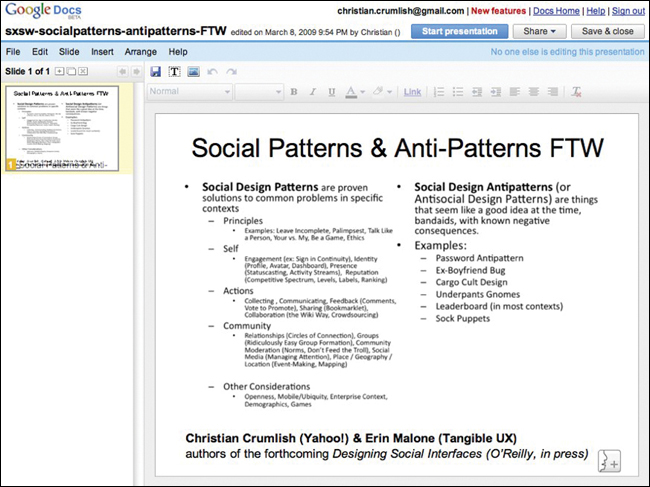

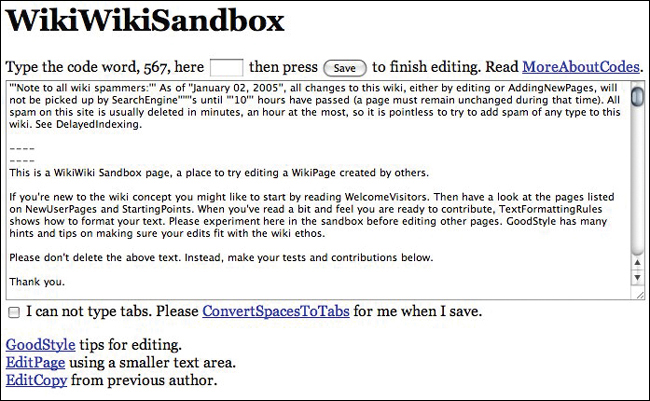

For direct editing, provide an edit box, similar to a blog or comment interface, such as that shown in Figure 1-9.

Figure 1-9. It doesn’t get more meta than this: here I am editing this very pattern in the collaborative wiki where it lives outside of the book. -

Optionally, give contributors mechanisms for tracking changes, whether via notifications or with RSS feeds.

Why

Collaborative editing is better suited to the online (web or cloud) contexts than the alternative: sending documents via email to multiple participants and then orchestrating the proliferating multiple, asynchronous updated copies of a document, with aspirational filenames ending in “finalFinalfinal,” as painfully demonstrated in Figure 1-10.

As seen on

Drupal (http://drupal.org/handbook/modules/book)

Google Docs (http://docs.google.com)

Mediawiki (http://mediawiki.org)

SocialText (http://socialtext.com)

SubEthaEdit (http://www.codingmonkeys.de/subethaedit/)

Twiki (http://www.twiki.org)

Wikipedia (http://wikipedia.org)

Writeboard (http://writeboard.com)

Numerous FAQ documents that accompany active Usenet newsgroups

Suggestions

Also known as suggested edits, proposed changes, tracked changes, or “track changes,” or pull request.

What

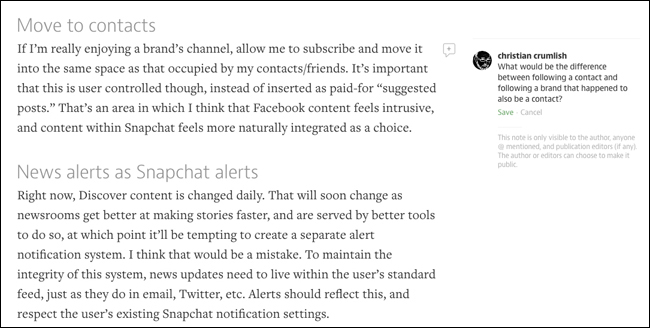

People like to be able to ask for help with a document without always wanting to give direct editing control over the content itself. Other people feel more comfortable proposing changes and allowing the owner of document to accept or reject the changes, as shown in Figure 1-11.

This same model applies outside of documents as well—for example, when a Git user makes a pull request, proposing that a change be added to the core.

Use when

Use this pattern when more fine-grained control over editing permissions or review flow will help people be more productive.

How

Define a role or a mode in which edits or comments are not accepted or made public automatically but are instead left in a pending state for review by the document owner, who can choose to accept or implement the suggestion, or reject or ignore it.

There are two forms of this pattern, which can be used individually or mixed together:

-

Pending edits (as with the Track Changes feature in Microsoft Word or the suggestion feature offered by Google Docs), in which a proposed edit is entered directly into the document and then either implemented or rejected.

-

Pending comments (as with Medium), in which a suggestion is made in the context around the document and not directly in the form of its content. The suggestion is then either made public or left hidden or removed.

Why

A layer of pending or proposed changes around a document makes room for discussion and deliberation and gives the owner of the document clarity about the final result.

As seen on

-

Medium

-

Google Docs

-

Git

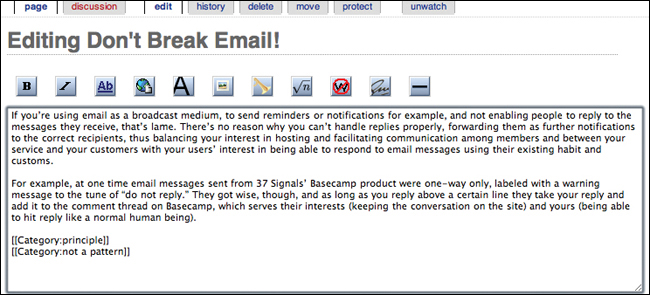

Edit This Page

What

The more difficult it is to edit a shared document, the fewer will be the number of people who will bother to do so. Even forcing people to switch contexts (to an “editing mode”) will create a barrier to participation for a significant fraction of potential contributors (see Figure 1-12).

This pattern is also known as “Edit This, “Universal Edit Button,” “Inline Editing,” “Read-Write Web,” or “Two-Way Web.”

Use when

Use this pattern in interfaces for editing shared or personal documents. You can use this for contexts in which universal editing, anonymous editing, or registered, authenticated, and privileged editing is permitted.

How

-

Provide a button or link on any editable content that links directly to an edit box for the content, preferably without even loading a new page, as illustrated in Figure 1-13.

Figure 1-13. If you can display an edit box directly in the reader’s original context, the experience of making and saving an edit and then resuming reading is smoother than if the editing must be done in a separate context. -

Optionally, when restricting editing only to privileged groups, hide the button from anyone who has not been authenticated as a contributor.

-

Consider providing a WYSIWYG editing environment. This will reduce one of the barriers to participation for the majority of people who are not comfortable using abbreviated markup languages to format and style text.

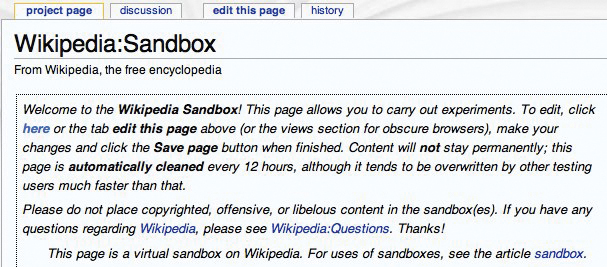

Special cases

When trying to cultivate a culture of collaborative editing, community moderators might need to make an extra effort to recruit, campaign, and encourage contributions. By default, many people are passive, even when invited to edit content, because they are afraid to break something or give offense to a preceding editor. The interface should be as inviting as possible, but be prepared to challenge incumbent behavioral patterns.

Offer a “sandbox” area for beginners (see Figure 1-14), in which they can practice editing safely without worrying about damaging anything or exposing themselves to criticism.

Why

The great promise of the Web draws in part from its facilitation of two-way communication and collaboration across geographical and other boundaries. An interface element that invites the reader to become an author goes beyond the “second-class” forms of participation, such as giving feedback and ratings. The easier you make it to edit content, the more likely people will take the time to do so, and potentially spur one another on to build knowledge stores and other projects that otherwise might never have come into being.

As seen on

Wikipedia (http://www.wikipedia.org)

Just about every wiki, everywhere

The Wiki Way

What

Collaborative editing can become bogged down in conversational mode. Moreover, when contributors become too attached to their own individual contributions, this can impede the development of the collaborative document (see Figure 1-15).

Use when

Use this pattern when providing an interface for collaborative editing.

How

Encourage anonymous editing, use version control, and enable refactoring of document content by contributors.

Here are the original principles Ward Cunningham cited when recalling the design principles that underpinned the first wiki:

- Open

-

Should a page be found to be incomplete or poorly organized, any reader can edit it as he sees fit.

- Incremental

-

Pages can cite other pages, including pages that have not been written yet.

- Organic

-

The structure and text content of the product are open to editing and evolution.

- Mundane

-

A small number of (irregular) text conventions will provide access to the most useful page markup.

- Universal

-

The mechanisms of editing and organizing are the same as those of writing; thus, any writer is automatically an editor and organizer.

- Overt

-

The formatted (and printed) output will suggest the input required to reproduce it.

- Unified

-

Page names will be drawn from a flat space so that no additional context is required to interpret them.

- Precise

-

Pages will be titled with sufficient precision to avoid most name clashes, typically by forming noun phrases.

- Tolerant

-

Interpretable (even if undesirable) behavior is preferred to error messages.

- Observable

-

Activity within the product can be watched and reviewed by any other visitor.

- Convergent

-

Duplication can be discouraged or removed by finding and citing similar or related content.

There are many wiki authors and implementers. Here are some additional principles that guide them, but were not of primary concern to me:

- Trust

-

This is the most important thing in a wiki. Trust the people, trust the process, foster trust-building. Everyone controls and checks the content. Wiki relies on the assumption that most readers have good intentions (but assume that there are limitations to good faith).

- Fun

-

Everybody can contribute, but nobody has to.

- Sharing

-

The dissemination of information, knowledge, experience, ideas, views, and so on is paramount.

Why

The wiki approach has unleashed a torrent of creativity on the Web and seems to have captured in its principles the fundamental grain of digital, electronic, web-enabled collaboration.

As seen on

WikiWikiWeb (http://c2.com/cgi/wiki)

Crowdsourcing

What

Some jobs are too big for the immediate group of engaged collaborators to manage on by itself. The community will benefit if the interface provides a way to break a large project into smaller pieces and engage and give incentives to a wider group of people (or “crowd”) to tackle those smaller pieces, as shown in Figure 1-16.

Use when

Use this pattern when you want your active core community members to engage with the wider set of people participating in your social environment and get their help accomplishing ambitious projects that would not be possible with fewer people.

How

-

Provide a method for splitting up a project into individual tasks so that each task can be advertised individually. Also, provide a venue for announcing crowdsourced projects.

-

Give community members a way to “shop for,” review, and claim individual tasks for the project.

-

Provide an upload interface or submission form with which participants can contribute their completed work (assuming the work isn’t accomplished directly in your interface).

-

Keep track of tasks that have been claimed but not completed by their deadline so that they can be returned to the general pool and reassigned.

-

Ideally, offer a dashboard view for management of the project.

-

Where appropriate, incorporate a mechanism for compensation for the participants.

Why

Crowdsourcing breaks large jobs into pieces that can be tackled with a much lower commitment threshold, taking advantage of the loose ties in social networks.

As seen on

Amazon Mechanical Turk (http://www.mturk.com/mturk/welcome)

Assignment Zero (http://zero.newassignment.net/)

The ESP Game (http://www.cs.cmu.edu/~biglou/ESP.pdf)

iStockphoto (http://istockphoto.com)

ReCAPTCHA (http://recaptcha.net/)

SETI@home (http://setiathome.ssl.berkeley.edu/)

Threadless (http://threadless.com)

Further Reading

-

“Berners-Lee on the read/write web.” BBC News, August 9, 2005. http://bbc.in/1gnkIGQ

-

Cross Cultural Collaboration. http://bit.ly/1gnkQWS

-

Marjanovic, Olivera, Hala Skaf-Molli, Pascal Molli, and Claude Godart. “Deriving Process-driven Collaborative Editing Pattern from Collaborative Learning Flow Patterns.” http://www.ifets.info/journals/10_1/12.pdf

-

Winer, Dave. Edit This Page. http://bit.ly/1gnlJ1F

-

Edit This Page PHP. http://bit.ly/1gnlO5F

-

Paylancers blog. http://paylancers.blogspot.com/

-

The Power of Many. http://thepowerofmany.com

-

Regulating Prominence: A Design Pattern for Co-Located Collaboration. http://bit.ly/1gnlQub

-

Howe, Jeff. “The Rise of Crowdsourcing.” Wired, 14.06. http://wrd.cm/1I2vKdB

-

Venners, Bill. “The Simplest Thing That Could Possibly Work.” http://www.artima.com/intv/simplest.html

-

Universal Edit Button. http://bit.ly/1I2vM5c

-

Wiki Design Principles. http://bit.ly/1I2vMlN

-

Udell, Jon The Wiki Way. http://bit.ly/1N4lsuI

-

Wired Crowdsourcing blog. http://crowdsourcing.typepad.com