Geospatial data and analysis for disaster relief

Tools from maps to drones respond to crises with increasing speed and accuracy.

On October 4, 2016, Hurricane Matthew made landfall on southwestern Haiti as a category-4 storm—the strongest storm to hit the Caribbean nation in more than 50 years. (source: NASA Earth Observatory image by Joshua Stevens on Wikimedia Commons)

On October 4, 2016, Hurricane Matthew made landfall on southwestern Haiti as a category-4 storm—the strongest storm to hit the Caribbean nation in more than 50 years. (source: NASA Earth Observatory image by Joshua Stevens on Wikimedia Commons)

In order to mount effective responses, emergency managers need accurate maps that show the extent of damage, predictions for its potential spread, and detailed data on the movement of people and resources.

Ten years ago, geospatial data wasn’t rich enough to map granular, real-time movements of people and resources, even in developed countries. Now that smartphones are ubiquitous around the world, disaster relief agencies are able to use geospatial data that goes down to the level of individuals, as well as maps showing key infrastructure and up-to-date damage assessments created on the fly, in order to manage response efforts.

The Humanitarian OpenStreetMap Team (HOT), discussed in Chapter 4, provides fast geospatial intelligence services during humanitarian crises. On October 3, 2016, as Hurricane Matthew bore down on the Caribbean, HOT activated a team to provide accurate, up-to-date maps of coastal areas in Jamaica, Haiti, and the Bahamas. A few days later, HOT announced that “over 1,000 mappers contributed more than 1.2 million edits, adding 180,000 buildings to the map concentrated in the most affected areas.” By the end of October, the effort had added more than 380,000 buildings and 400,000 road segments to the basemap, mostly in Haiti and the Dominican Republic.

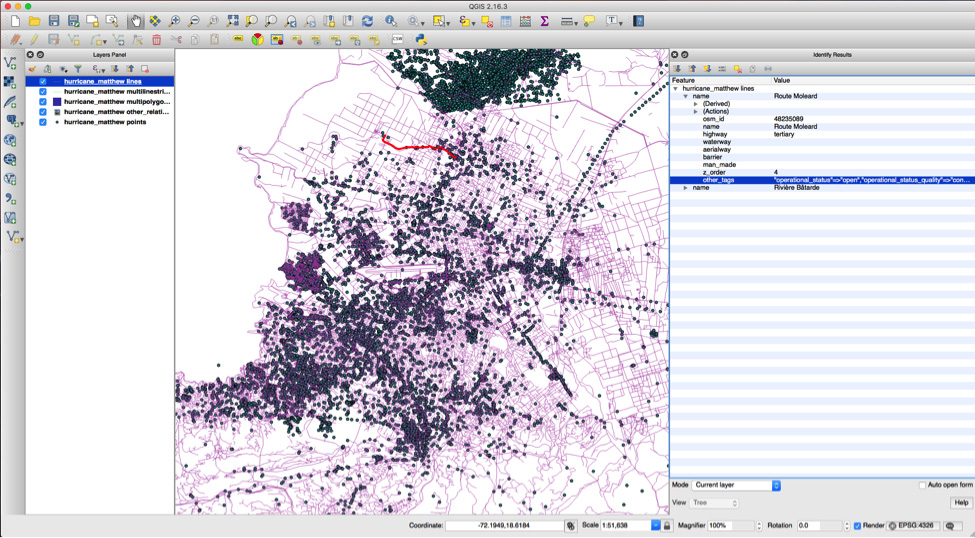

HOT contributors respond to a list of projects posted by organizations like the Red Cross. Tasks might include identifying buildings and tracing roads from aerial imagery (Figure 1), and contributors may also gather data firsthand, as in a current HOT project that aims to map water and sanitation resources in Tanzania.

HOT, which has been working since 2011, principally uses satellite imagery supplemented with on-the-ground GPS-based data gathering. The future will almost certainly involve drones and sophisticated software that can stitch images together in order to produce up-to-the-minute surveys of conditions in disaster-stricken areas.

Skycatch, a San Francisco startup founded in 2013, produces software that transforms drone videos into 3D models. It normally sells its software to construction companies working on megaprojects, but it found a new application in 2015 when it joined the relief effort following Nepal’s massive earthquake. Data from the drones was used to identify damaged buildings, map paths for heavy equipment, and plan for the restoration of heritage sites.

Satellites and drones can capture outstanding surveys of infrastructure, but for tracking people after a disaster, phone data is becoming indispensable. Flowminder, a Swedish not-for-profit organization, demonstrated that anonymized call records from mobile phone operators could be used to map flows of displaced people following the 2010 earthquake in Haiti, and updated its model immediately before the 2015 Nepal earthquake.

Following that disaster, Flowminder used anonymized data from 12 million phones to estimate population displacement, including gender and age distributions, down to 100m resolution. Following the disaster, each day the Nepalese mobile provider Ncell delivered a 12-gigabyte CSV file to Flowminder, which reformed the data, assigned call locations to administrative regions, and interpreted migration patterns.

Stefan Avesand, an engineer at Spotify who previously led efforts at Ericsson related to mobile network data, says Flowminder’s work during the Haiti earthquake response is an example of the transformation “from gut-driven to data-driven decision-making,” by “linking data collection directly with the decision-making process.”