Logs and real-time stream processing

Chapter 3 from I Heart Logs.

"Pair of Strutting Birds Dance a Jig" (source: Wikimedia Commons)

"Pair of Strutting Birds Dance a Jig" (source: Wikimedia Commons)

So far, I have only described what amounts to a fancy method of copying data from place to place. However, schlepping bytes between storage systems is not the end of the story. It turns out that “log” is another word for “stream” and logs are at the heart of stream processing.

But wait, what exactly is stream processing?

If you are a fan of database literature or semi-successful data infrastructure products of the late 1990s and early 2000s, you likely associate stream processing with efforts to build a SQL engine or “boxes-and-arrows” interface for event-driven processing.

If you follow the explosion of open source data systems, you likely associate stream processing with some of the systems in this space, for example, Storm, Akka, S4, and Samza. Most people see these as a kind of asynchronous message processing system that is not that different from a cluster-aware RPC layer (and in fact some things in this space are exactly that). I have heard stream processing described as a model where you process all your data immediately and then throw it away.

Both these views are a little limited. Stream processing has nothing to do with SQL. Nor is it limited to real-time processing. There is no inherent reason you can’t process the stream of data from yesterday or a month ago using a variety of different languages to express the computation. Nor must you (or should you) throw away the original data that was captured.

I see stream processing as something much broader: infrastructure for continuous data processing. I think the computational model can be as general as MapReduce or other distributed processing frameworks, but with the ability to produce low-latency results.

The real driver for the processing model is the method of data collection. Data collected in batch is naturally processed in batch. When data is collected continuously, it is naturally processed continuously.

The United States census provides a good example of batch data collection. The census periodically kicks off and does a brute force discovery and enumeration of US citizens by having people walk from door to door. This made a lot of sense in 1790 when the census was first begun (see Figure 1-1). Data collection at the time was inherently batch oriented, as it involved riding around on horseback and writing down records on paper, then transporting this batch of records to a central location where humans added up all the counts. These days, when you describe the census process, one immediately wonders why we don’t keep a journal of births and deaths and produce population counts either continuously or with whatever granularity is needed.

This is an extreme example, but many data transfer processes still depend on taking periodic dumps and bulk transfer and integration. The only natural way to process a bulk dump is with a batch process. As these processes are replaced with continuous feeds, we naturally start to move towards continuous processing to smooth out the processing resources needed and reduce latency.

A modern web company does not need to have any batch data collection at all. The data a website generates is either activity data or database changes, both of which occur continuously. In fact, when you think about any business, the underlying mechanics are almost always a continuous process—events happen in real-time, as Jack Bauer would tell us. When data is collected in batches, it is almost always due to some manual step or lack of digitization, or it is a historical relic left over from the automation of some nondigital process. Transmitting and reacting to data used to be very slow when the mechanics involved transporting pieces of paper and humans did the processing. A first pass at automation always retains the form of the original process, so this often lingers long after the medium has changed.

Production “batch” processing jobs that run every day are often effectively mimicking a kind of continuous computation with a window size of one day. The underlying data is, of course, always changing.

This helps to clear up one common area of confusion about stream processing. It is commonly believed that certain kinds of processing cannot be done in a stream processing system and must be done in batch. A typical example I have heard used is computing percentiles, maximums, averages, or other summary statistics that require seeing all the data. But this somewhat confuses the issue. It is true that with computing, for example, the maximum is a blocking operation that requires seeing all the records in the window in order to choose the biggest record. This kind of computation can absolutely be carried out in a stream processing system. Indeed, if you look at the earliest academic literature on stream processing, virtually the first thing that is done is to give precise semantics to windowing so that blocking operations over the window are still possible.

Seen in this light, it is easy to share my view of stream processing, which is much more general: it has nothing to do with blocking versus nonblocking operations; it is just processing that includes a notion of time in the underlying data being processed and so does not require a static snapshot of the data on which to operate. This means that a stream processing system produces output at a user-controlled frequency instead of waiting for the “end” of the data set to be reached. In this sense, stream processing is a generalization of batch processing and, given the prevalence of real-time data, a very important generalization.

So why has the traditional view of stream processing been as a niche application? I think the biggest reason is that a lack of real-time data collection made continuous processing something of a theoretical concern.

Certainly I think the lack of real-time data collection is likely what doomed the commercial stream processing systems. Their customers were still doing file-oriented, daily batch processing for ETL and data integration. Companies building stream processing systems focused on providing processing engines to attach to real-time data streams, but it turned out that at the time very few people actually had real-time data streams. Actually, very early at my career at LinkedIn, a company tried to sell us a very cool stream processing system, but since all our data was collected in hourly files at that time, the only thing we could think to do with it was take the hourly files we collected and feed them into the stream system at the end of the hour! The engineers at the stream processing company noted that this was a fairly common problem. The exception actually proves the rule here: finance, the one domain where stream processing has met with some success, was exactly the area where real-time data streams were already the norm, and processing the data stream was the pressing concern.

Even in the presence of a healthy batch processing ecosystem, the actual applicability of stream processing as an infrastructure style is quite broad. It covers the gap in infrastructure between real-time request/response services and offline batch processing. For modern Internet companies, I think around 25 percent of their code falls into this category.

It turns out that the log solves some of the most critical technical problems in stream processing, which I’ll describe, but the biggest problem that it solves is just making data available in real-time multisubscriber data feeds.

For those interested in more details on the relationship between logs and stream processing, we have open-sourced Samza, a stream processing system explicitly built on many of these ideas. We describe many of these applications in more detail in the documentation. But this is not specific to a particular stream processing system, as all the major stream processing systems have some integration with Kafka to act as a log of data for them to process.

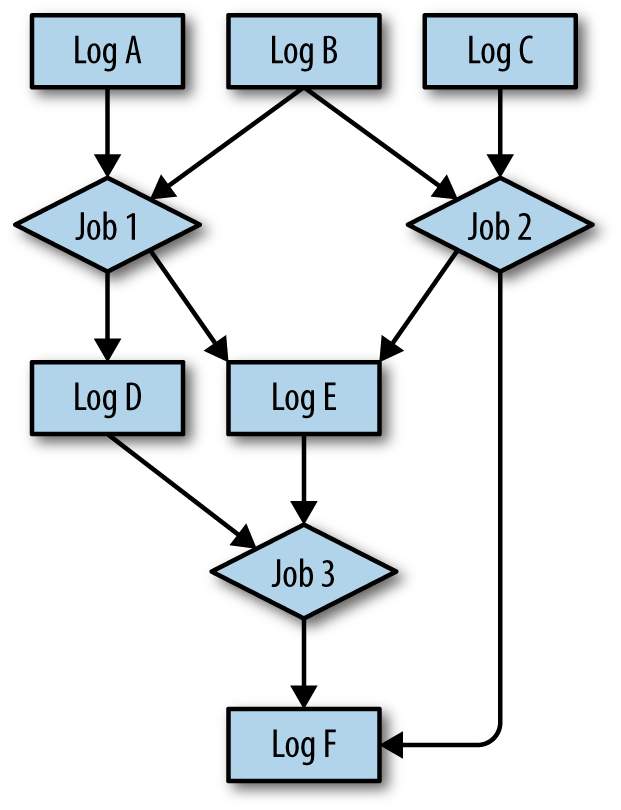

Data Flow Graphs

The most interesting aspect of stream processing has nothing to do with the internals of a stream processing system, but instead with how it extends our idea of what a data feed is from the earlier data integration discussion. We discussed primarily feeds or logs of primary data—that is, the events and rows of data directly produced in the execution of various applications. Stream processing allows us to also include feeds computed off of other feeds. These derived feeds look no different to consumers than the feeds of primary data from which they are computed (see Figure 1-2).

These derived feeds can encapsulate arbitrary complexity and intelligence in the processing, so they can be quite valuable. For example, Google has described some details on how it rebuilt its web crawling, processing, and indexing pipeline—what has to be one of the most complex, largest scale data processing systems on the planet—on top of a stream processing system.

So what is stream processing? A stream processing job, for our purposes, will be anything that reads from logs and writes output to logs or other systems. The logs used for input and output connect these processes into a graph of processing stages. Using a centralized log in this fashion, you can view all the organization’s data capture, transformation, and flow as just a series of logs and the processes that read from them and write to them.

A stream processor doesn’t necessarily need to have a fancy framework at all; it can be any process or set of processes that read and write from logs. Additional infrastructure and support can be provided for helping manage and scale this kind of near-real-time processing code, and that is what stream processing frameworks do.

Logs and Stream Processing

Why do you need a log at all in stream processing? Why not have the processors communicate more directly using simple TCP or other lighter-weight messaging protocols? There are a couple of strong reasons to favor this model.

First, it makes each data set to be multisubscriber. Each stream processing input is available to any processor that wants it; and each output is available to anyone who needs it. This comes in handy not just for the production data flows, but also for debugging and monitoring stages in a complex data processing pipeline. Being able to quickly tap into an output stream and check its validity, compute some monitoring statistics, or even just see what the data looks like make development much more tractable.

The second use of the log is to ensure that order is maintained in the processing done by each consumer of data. Some event data might be only loosely ordered by timestamp, but not everything is this way. Consider a stream of updates from a database. We might have a series of stream processing jobs that take this data and prepare it for indexing in a search index. If we process two updates to the same record out of order, we might end up with the wrong final result in our search index.

The final use of the log is arguably the most important, and that is to provide buffering and isolation to the individual processes. If a processor produces output faster than its downstream consumer can keep up, we have three options:

- We can block the upstream job until the downstream job catches up (if using only TCP and no log, this is what would likely happen).

- We can just drop data on the floor.

- We can buffer data between the two processes.

Dropping data will be okay in a few areas, but is not generally acceptable, and is never really desirable.

Blocking sounds like an acceptable option at first, but in practice becomes a huge issue. Consider that what we want is not just to model the processing of a single application but to model the full data flow of the whole organization. This will inevitably be a very complex web of data flow between processors owned by different teams and run with different SLAs. In this complicated web of data processing, if any consumer fails or cannot keep up, upstream producers will block, and blocking will cascade up throughout the data-flow graph, grinding everything to a halt.

This leaves the only real option: buffering. The log acts as a very, very large buffer that allows the process to be restarted or fail without slowing down other parts of the processing graph. This means that a consumer can come down entirely for long periods of time without impacting any of the upstream graph; as long as it is able to catch up when it restarts, everything else is unaffected.

This is not an uncommon pattern elsewhere. Big, complex MapReduce workflows use files to checkpoint and share their intermediate results. Big, complex SQL processing pipelines create lots and lots of intermediate or temporary tables. This just applies the pattern with an abstraction that is suitable for data in motion, namely a log.

Storm and Samza are two stream processing systems built in this fashion, and can use Kafka or other similar systems as their log.

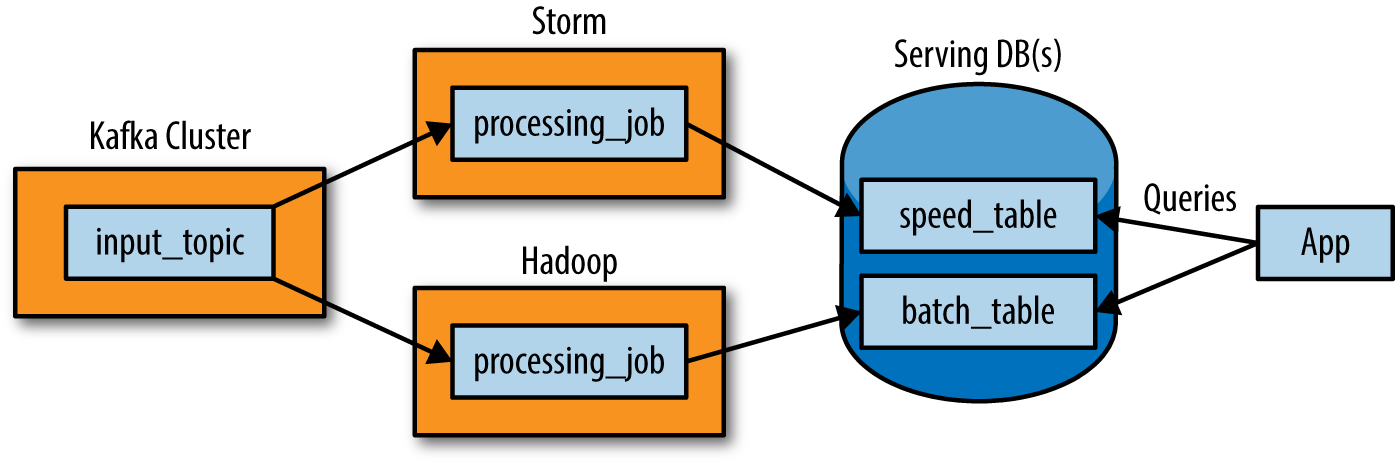

Reprocessing Data: The Lambda Architecture and an Alternative

An interesting application of this kind of log-oriented data modeling is the Lambda Architecture. This is an idea introduced by Nathan Marz, who wrote a widely read blog post describing an approach to combining stream processing with offline processing (“How to beat the CAP theorem”). This has proven to be a surprisingly popular idea, with a dedicated website and an upcoming book.

What is a Lambda Architecture and How Do I Become One?

The Lambda Architecture looks something like Figure 1-3.

The way this works is that an immutable sequence of records is captured and fed into a batch-and-stream processing system in parallel. You implement your transformation logic twice, once in the batch system and once in the stream processing system. Then you stitch together the results from both at query time to produce a complete answer.

There are many variations on this, and I’m intentionally simplifying a bit. For example, you can swap in various similar systems for Kafka, Storm, and Hadoop, and people often use two different databases to store the output tables: one optimized for real-time and the other optimized for batch updates.

What’s Good About This?

The Lambda Architecture emphasizes retaining the original input data unchanged. I think this is a really important aspect. The ability to operate on a complex data flow is greatly aided by the ability to see what inputs went in and what outputs came out.

I also like that this architecture highlights the problem of reprocessing data. Reprocessing is one of the key challenges of stream processing, but is very often ignored.

By “reprocessing,” I mean processing input data over again to re-derive output. This is a completely obvious but often ignored requirement. Code will always change. So if you have code that derives output data from an input stream, whenever the code changes, you will need to recompute your output to see the effect of the change.

Why does code change? It may change because your application evolves and you want to compute new output fields that you didn’t previously need. Or it may change because you found a bug and need to fix it. Regardless, when it does, you need to regenerate your output. I have found that many people who attempt to build real-time data processing systems don’t put much thought into this problem and end up with a system that simply cannot evolve quickly because it has no convenient way to handle reprocessing.

And the Bad…

The problem with the Lambda Architecture is that maintaining code that needs to produce the same result in two complex distributed systems is exactly as painful as it seems it would be. I don’t think this problem is fixable.

Distributed frameworks like Storm and Hadoop are complex to program. Inevitably, code ends up being specifically engineered towards the framework on which it runs. The resulting operational complexity of systems implementing the Lambda Architecture is the one thing that seems to be universally agreed on by everyone doing it.

One proposed approach to fixing this is to have a language or framework that abstracts over both the real-time and batch framework. You write your code using this higher-level framework and then it “compiles down” to stream processing or MapReduce under the covers. Summingbird is a framework that does this. This definitely makes things a little better, but I don’t think it solves the problem. Ultimately, even if you can avoid coding your application twice, the operational burden of running and debugging two systems is going to be very high. Any new abstraction can only provide the features supported by the intersection of the two systems. Worse, committing to this new uber-framework walls off the rich ecosystem of tools and languages that makes Hadoop so powerful (Hive, Pig, Crunch, Cascading, Oozie, and so on).

By way of analogy, consider the notorious difficulties in making cross-database object-relational mapping (ORM) really transparent. And consider that this is just a matter of abstracting over very similar systems providing virtually identical capabilities with a (nearly) standardized interface language. The problem of abstracting over totally divergent programming paradigms built on top of barely stable distributed systems is much harder.

An Alternative

As someone who designs infrastructure, I think that the glaring question is this: why can’t the stream processing system just be improved to really handle the full problem set in its target domain? Why do you need to glue on another system? Why can’t you do both real-time processing and also handle the reprocessing when code changes? Stream processing systems already have a notion of parallelism, why not just handle reprocessing by increasing the parallelism and replaying history very quickly? The answer is that you can do this, and I think this is actually a reasonable alternative architecture if you are building this type of system today.

When I’ve discussed this with people, they sometimes tell me that stream processing feels inappropriate for high-throughput processing of historical data. This is an intuition based mostly on the limitations of systems they have used, which either scale poorly or can’t save historical data. There is no reason this should be true. The fundamental abstraction in stream processing is data-flow DAGs, which are exactly the same underlying abstraction in a traditional data warehouse (such as Volcano), as well as being the fundamental abstraction in the MapReduce successor Tez. Stream processing is just a generalization of this data-flow model that exposes checkpointing of intermediate results and continual output to the end user.

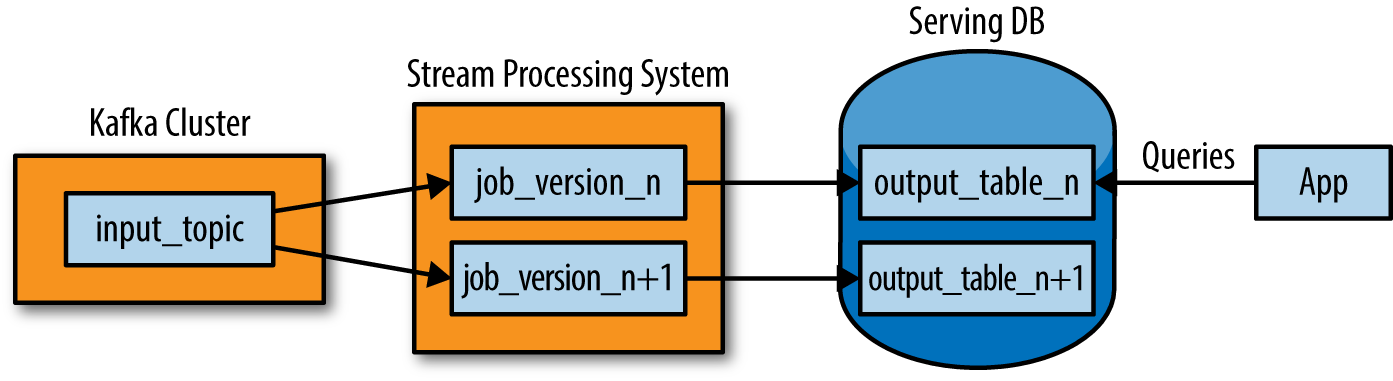

So how can we do the reprocessing directly from our stream processing job? My preferred approach is actually stupidly simple:

- Use Kafka or some other system that will let you retain the full log of the data you want to be able to reprocess and that allows for multiple subscribers. For example, if you will want to reprocess up to 30 days of data, set your retention in Kafka to 30 days.

- When you want to do the reprocessing, start a second instance of your stream processing job that starts processing from the beginning of the retained data, but direct this output data to a new output table.

- When the second job has caught up, switch the application to read from the new table.

- Stop the old version of the job and delete the old output table.

This architecture looks something like Figure 1-4.

Unlike the Lambda Architecture, in this approach you only do reprocessing when your processing code changes and you actually need to recompute your results. And of course the job doing the recomputation is just an improved version of the same code, running on the same framework, taking the same input data.

Naturally, you will want to bump up the parallelism on your reprocessing job so it completes very quickly.

Of course, you can optimize this further. In many cases you could combine the two output tables. However, I think there are some benefits to having both for a short period of time. This allows you to revert back instantaneously to the old logic by just having a button that redirects the application to the old table. And in cases that are particularly important (your ad targeting criteria, say), you can control the cutover with an automatic A/B test or bandit algorithm to ensure that whatever bug fix or code improvement you are rolling out hasn’t accidentally degraded things in comparison to the prior version.

Note that this doesn’t mean your data can’t go to Hadoop, it just means that you don’t run your reprocessing there. Kafka has good integration with Hadoop, so loading any Kafka topic is easy. It is often useful for the output or even intermediate streams from a stream processing job to be mirrored to Hadoop for analysis in tools such as Hive, or for use as input for other, offline data processing flows.

We have documented implementing this approach, as well as other variations on re-processing architectures using Samza.

The efficiency and resource trade-offs between the two approaches are somewhat of a wash. The Lambda Architecture requires running both reprocessing and live processing all the time, whereas what I have proposed only requires running the second copy of the job when you need reprocessing. However, my proposal requires temporarily having twice the storage space in the output database and requires a database that supports high-volume writes for the reload. In both cases, the extra load of the reprocessing would likely average out. If you had many such jobs, they wouldn’t all reprocess at once, so on a shared cluster with several dozen such jobs you might budget an extra few percent of capacity for the few jobs that would be actively reprocessing at any given time.

The real advantage isn’t about efficiency at all, but rather about allowing people to develop, test, debug, and operate their system on top of a single processing framework.

So in cases where simplicity is important, consider this approach as another option in addition to the Lambda Architecture.

Stateful Real-Time Processing

The relationship of logs to stream processing doesn’t end with reprocessing. If the actual computations the stream processing system do require maintaining state, then that is yet another use for our good friend, the log.

Some real-time stream processing is just stateless record-at-a-time transformation, but many of the uses are more sophisticated counts, aggregations, or joins over windows in the stream. You might, for example, want to enrich an event stream (say a stream of clicks) with information about the user doing the click, in effect joining the click stream to the user account database. Invariably, this kind of processing ends up requiring some kind of state to be maintained by the processor; for example, when computing a count, you have the count so far to maintain. How can this kind of state be maintained correctly if the processors themselves can fail?

The simplest alternative would be to keep state in memory. However, if the process crashed, it would lose its intermediate state. If state is only maintained over a window, the process could just fall back to the point in the log where the window began. However, if one is doing a count over an hour, this might not be feasible.

An alternative is to simply store all state in a remote storage system and join over the network to that store. The problem with this is that there is no locality of data and lots of network round trips.

How can we support something like a table that is partitioned with our processing?

Well, recall the discussion of the duality of tables and logs. This gives us exactly the tool to be able to convert streams to tables colocated with our processing, as well as a mechanism for handling fault tolerance for these tables.

A stream processor can keep its state in a local table or index: a bdb, RocksDB, or even something more unusual such as a Lucene or fastbit index. The contents of this store are fed from its input streams (after first perhaps applying arbitrary transformation). It can journal out a changelog for this local index that it keeps to allow it to restore its state in the event of a crash and restart. This allows a generic mechanism for keeping co-partitioned states in arbitrary index types local with the incoming stream data.

When the process fails, it restores its index from the changelog. The log is the transformation of the local state into an incremental record-at-a-time backup.

This approach to state management has the elegant property that the state of the processors is also maintained as a log. We can think of this log just like we would the log of changes to a database table. In fact, the processors have something very like a co-partitioned table maintained along with them. Since this state is itself a log, other processors can subscribe to it. This can actually be quite useful in cases when the goal of the processing is to update a final state that is the natural output of the processing.

When combined with the logs coming out of databases for data integration purposes, the power of the log/table duality becomes clear. A changelog can be extracted from a database and indexed in different forms by various stream processors to join against event streams.

We give more detail on this style of managing stateful processing in Samza and many more practical examples.

Log Compaction

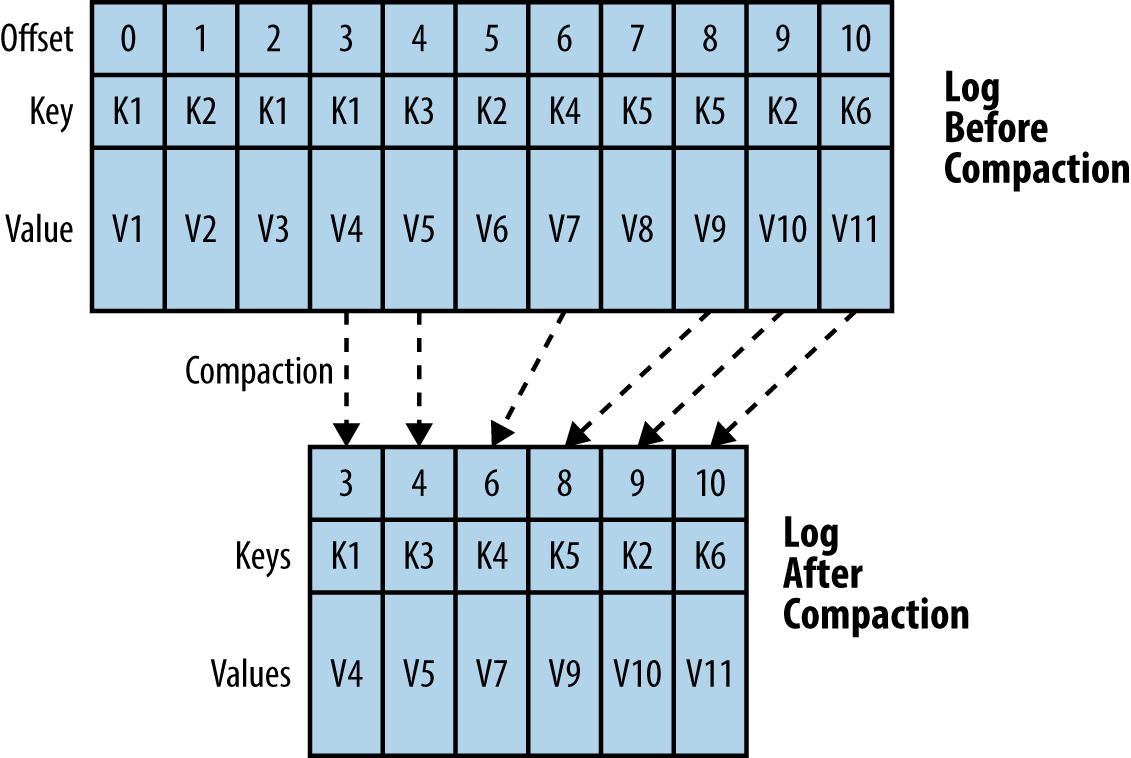

Of course, we can’t hope to keep a complete log for all state changes for all time. Unless you want to use infinite space, somehow the log must be cleaned up. I’ll talk a little about the implementation of this in Kafka to make it more concrete.

In Kafka, cleanup has two options depending on whether the data contains pure event data or keyed updates. By event data, I mean unrelated occurrences such as page views, clicks, or other things you would find in an application log. By keyed updates, I mean events that specifically record state changes in entities identified by some key. The changelog of a database is the prototypical example of this.

For event data, Kafka supports retaining a window of data. The window can be defined in terms of either time (days) or space (GBs), and most people just stick with the one week default retention. If you want infinite retention, just set this window to infinite and your data will never be thrown away.

For keyed data, however, a nice property of a complete log is that you can replay it to recreate the state of the source system. That is, if I have the log of changes, I can replay that log into a table in another database and recreate the state of the table at any point in time. This also works across different systems: you can replay a log of updates that originally went into a database into any other type of system that maintains data by primary key (a search index, a local store, and so on).

However, retaining the complete log will use more and more space as time goes by, and the replay will take longer and longer. Hence, in Kafka, we support a different type of retention aimed at supporting this use case, an example of which is shown in Figure 1-5. Instead of simply throwing away the old log entirely, we garbage-collect obsolete records from the tail of the log. Any record in the tail of the log that has a more recent update is eligible for this kind of cleanup. By doing this, we still guarantee that the log contains a complete backup of the source system, but now we can no longer recreate all previous states of the source system, only the more recent ones. We call this feature log compaction.