Chapter 4. Turner Broadcasting Company: Dedicated to the Cloud for its Data-Driven Journey

Vikram Marathe is technical director of development and architecture for the Turner Data Cloud (TDC) at Turner Broadcasting. He’s been at Turner for slightly more than four years. At the beginning of that time, Turner was just exploring how it could use data to better align with audiences. Then, in 2015, Turner created the TDC, which brings together numerous first- and third-party data sources with advanced analytics so that Turner can better anticipate consumer behavior.

Today, everybody in the industry now understands that the more data you have, the more useful it becomes, says Marathe. “And to gather more data, you need more ways to reach out to more consumers. That’s why we’re seeing so much consolidation in the media and entertainment industry right now.”

The impetus for Turner to create the TDC was realizing that it needed to invest in technologies to build an integrated enterprise-wide big data platform. “The ultimate goal is to get a 360-degree view of consumers that encompasses understanding their past, present, and future behaviors,” says Marathe. TDC supports Turner’s initiatives in enabling Turner to tailor content, marketing, and advertisements based on its understanding of consumers’ preferences. By bringing together numerous data sources, the TDC enables Turner to deliver more relevant consumer experiences while offering advertisers more effective ways to reach target audiences.

Turner can now utilize this data to acquire or create new shows that are likely to appeal to the audiences that watch its portfolio of channels, which includes TBS, TNT, TCM, Adult Swim, CNN, HLN, and others. Turner has also been able to take advantage of this data to identify the right audiences for new Time Warner movies. These marketing campaigns are omni-channel and can target prospective audiences wherever they are, whether they are watching broadcast television or cable, or perusing digital channels like Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.

“When we started leveraging TDC data it was quite uncommon for media and entertainment companies to be data driven. However, most media companies today either have similar initiatives or are embarking on them,” says Marathe.

What Made Turner Turn Toward Data

Previously, like most cable channel operators, Turner didn’t use data to make decisions. However, consumers today have many more options for entertainment beyond linear TV channels. Because of the nature of their businesses, video-on-demand services and digital-channel operators have tremendous amounts of data about each consumer’s behavior at their fingertips. It thus became an imperative for Turner to better understand its customers. This was not an easy task, however, given that channel operators do not own the relationships with their customers. Their consumers happen to be customers of cable companies or telecom companies.

On the digital side of Turner’s operations—that is, on its websites and apps—data was always important. Yet use of this data was limited compared to what Turner does today. “We considered certain metrics, but the bulk of advertising revenue at Turner originated from linear sources, and hence digital channels were used more to increase consumers’ engagement with our linear TV operations,” says Marathe.

Today, cable operators must compete with digital channels such as Facebook and Google for advertising dollars. These digital providers can target advertisements to specific segments of consumers, whereas advertising in linear television is still mostly based on demographics. Turner would sell advertising time slots to advertisers based on guaranteeing “a certain number of males or females, between certain age ranges.” When those were the only options available for advertisers, they were not good enough.

As more and more consumers “cut the cord”—getting rid of their cable services—Turner and its competitors have to make sure that their channels are must-see propositions, and something that consumers can’t do without. This shift has been going on for some time, but it has reached a point where the industry has to take notice and retool how it has done things in the past.

“Data is rapidly becoming central to everything Turner does,” says Marathe, who added that the transition to a data-driven culture started approximately four years ago, and was one of the reasons he was recruited by Turner.

At that time, Turner was using Netezza as the underlying technology for its data platform. It performed some analytics for the digital side of the house, but that was more for research teams to publish stats for advertisers than for general business users to employ. For example, Turner would track how many visitors came to its sites, how many of them were unique, how many page views accrued, and other like metrics. “It really did not go too much beyond that,” says Marathe.

But the week he arrived at Turner, his group began learning about Hadoop and figuring out how to create a data lake using the firm’s new onsite Hadoop cluster. This platform became the firm’s mainstay for the next two years. Then, Marathe began looking at other options, particularly moving to the cloud. “That’s when I started looking at various vendors,” he says. “Last year we moved to the cloud and began utilizing the Qubole platform.”

Marathe notes that the data management industry has also been changing rapidly, during the same timeframe that data at Turner has become so prominent. Cloud adoption and cloud tools for data management have vastly improved in the past four years. “If you are an on-premises company, you can only store so much data. You have to keep adding more and more servers to your Hadoop platform,” says Marathe. “That’s not always easy to do, and it doesn’t necessarily scale when you need it to scale. So, moving to the cloud was—and is—essential.”

He adds that cloud technology has been sharply focused on data management, beyond its roots in just running apps and websites. Turner must use the knowledge it is getting from its new cloud-based big data analytics to provide more engaging content along with more relevant ads and marketing.

Turner currently has about 150 internal users for its TDC. The biggest advantage for these users is time to market of new shows, initiatives, and services. Previously, transforming data and creating new data structures was very time consuming. But now, because of the data lake with schema-on-read and the power of new big data processing technologies, users can just begin asking questions of the data. They can change what they’re asking for, and Turner’s team can quickly answer them without having to retransform that data into a different data structure.

“Happily, the days when it would take three months before we could get to a request, and another three months before we could deliver it to them, are long gone,” he says.

Moving up the Big Data Maturity Model

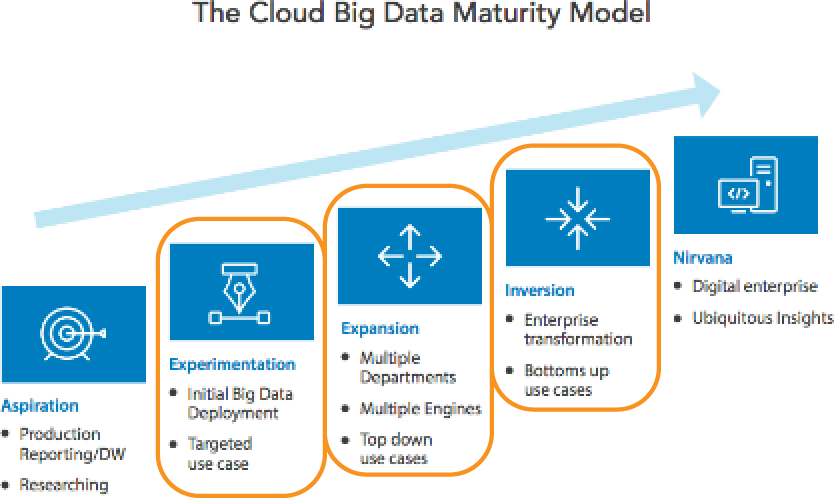

Depending on the group and their use cases, data usage at Turner straddles the three middle stages of the big data maturity model: experimentation, expansion, and inversion (see Figure 4-1).

Figure 4-1. Turner Broadcasting straddles the three middle stages of the Data-Driven Maturity Model: experimentation, expansion, and inversion

“In the experimentation stage, we are bringing in new data sets all the time in to the Turner Data Cloud,” says Marathe. “In these cases, we need to figure out, ‘how do we use these datasets?’ How do we create new initiatives and services based on them?”

Also in the experimentation stage, Turner has datasets that multiple departments are already using. But these datasets are very large and very diverse, so business users are still figuring out how to use them, what types of analytics can be run on them, and how to build new business strategies around them.

Then, Turner has some groups in the expansion stage of the Data-Driven Maturity Model. For example, business users from its revenue operations use data from the TDC to forecast ad inventory. Turner also uses data to determine which audiences to target—because more and more ads are now being sold using knowledge about audience preferences rather than demographics. “By doing this, we get a much higher CPM [cost per thousand impressions] than if the ads we sold were just based on demographics,” says Maranthe.

This same data is being used by brands to figure out what content is best suitable for the audiences that Turner already has. The data is also used by Turner’s research team to create reports and forecasts of the business for upper management. “Multiple groups are leveraging the same data, just slicing and dicing it in different ways to suit their requirements,” says Marathe.

Finally, Turner does have a few teams in the inversion stage of the Data-Driven Maturity Model. “This is where we brought in extra datasets and started building more centers of excellence around data, or data COEs [Centers of Excellence],” says Marathe. Until recently, the users of Turner’s data were not operating like data COEs. But today it has data COEs within its various brands.

The Evolution of the Turner Data Team

Four teams are involved in managing the TDC: Marathe’s IT group (called the data engineering group), a data governance group, a business engagement group, and a data scientist group.

Before Turner created the TDC, Marathe’s group was called Audience Insights Reporting, and was quite limited in what it did. “Whereas the mission of the Turner Data Cloud is to get the best possible alignment of consumers and content, our earlier mission was simply reporting certain basic statistics,” he says. “The new mission is reporting plus analytics plus everything in between.”

Marathe has dedicated two of his 30 engineers to R&D and innovation. “I need this because the data field is changing so fast,” he says. “Every day there is some new tool, whether it’s a new AWS [Amazon Web Services] product, or enhancements to our Qubole platform or a Spark innovation. Something is always changing. And we want to make sure that we keep abreast of it all.”

Marathe says he considers Turner’s architecture well structured to benefit from all the innovations coming from the cloud providers, the open source community, and from their Hadoop/Spark platform—Qubole. “As new tools come up or as new data processing platforms become available, we have the ability to shift to them fairly quickly. Our users will always have access to the latest and the greatest. That’s the cornerstone of the architecture and that’s what cloud affords us, which we couldn’t have done if we were based on an on-premises architecture.”

Within his IT group, Marathe has a development and quality assurance team responsible for developing processes to bring in new data sources, by first extracting data through various means such as APIs and data feeds, and then transforming and loading that data into a data lake or, for some sources, into a data warehouse. In addition, Marathe has a small development/maintenance and operations team—a team of data architects who are also data analysts, and who analyze new data sources or use cases and figure out what kinds of transformations and models would serve those use cases.

Though the team’s goal is always to do as little data transformation as possible, Marathe says, “we try to keep data in a data lake format, and do schema-on-read. So, we try not to do extensive ETL [extract, transform, and load] activities.”

Moving Toward User Self-Service

When it comes to putting self-service in place for data users, Turner is currently “all over the map.” According to Marathe, “For some business groups, we are already doing that. We have given users a business intelligence platform, and they are quite self-sufficient.” But then there are many users who are not independent—yet. Turner’s goal is to democratize data, and to make most of its users self-sufficient in using it.

However, says Marathe, there will always be a data science team within the TDC to perform tasks for smaller business groups within Turner that will never hire data scientists of their own.

“We’ll always have a hybrid model for that reason. Self-service will mostly be the domain of the larger business units,” he says.

Challenges and Next Steps

The biggest challenge Turner has faced thus far is data wrangling. Just the day-to-day chore of bringing in quality data has turned out to be extraordinarily difficult. “We bring in and ingest so much data and so many social media files that it’s an ongoing challenge,” says Marathe. “But it’s smaller today compared to the previous model, where we had to do a lot of ETL and a slight variation in data would throw it off.”

Marathe doesn’t consider the big data infrastructure challenges facing the media industry to be unique. “Most of the challenges we face are common to all industries,” he says. “In a way, we have less concerns when compared to industries like finance and banking and healthcare where they own, store, and process a lot of PII [personally identifiable information] data. We don’t have that much PII. But we still have to make sure that we are abiding by all the different laws and regulations—especially now that Europe is implementing GDPR [General Data Protection Regulation].” Complying with everything that is in the European GDPR is going to keep Turner busy for next few months, Marathe admits. However, that’s something all businesses in all industries need to do, and it will ensure that no industry misuses people’s personal information. Marathe believes this measure will be a good thing in the long term for the data technologies.

One challenge that is unique to the media industry is that the data it gets can have many quality issues compared to other industries. Take financial services—core financial industry data has to be very clean. When you go to an ATM and withdraw money, the data says that the $100 you withdrew is a $100 debit transaction from your account. “But when you visit a broadcaster’s web page, not all the data is always collected. This is because the web page needs to be rendered quickly and time is important. “We can’t spend a lot of time collecting and sending data, so if there are any hiccups we may not get all the data fields that we want to collect” Marathe says. “So, data quality is perhaps one aspect of data that is particularly challenging to media companies.”

Marathe says Turner completely believes in the DataOps way of working. “In the old world, where we did a lot of ETL, we were always challenged because by the time we finished doing ETL, our business users would have new questions or they would have moved on. Putting data and ops teams together has increased velocity,” he says. “It’s less of a problem now because we are constantly working with them, collaborating with them, and doing as little transformation to the data as possible. We are now always in sync.”

Marathe stays in close touch with users. He schedules regular meetings with Turner’s business units, which include data scientists as well as users. And, as previously mentioned, Turner also has a group within the TDC devoted exclusively to what it calls “business engagement.” “For example, within that group, we have a person dedicated to CNN. A person is dedicated to Turner Sports, and so on,” says Marathe. “All this ensures that we are very close to our users.”

With his team, which is more on the technical side, Marathe will typically have biweekly meetings with users—mainly the data scientists from the various business units, to see what challenges they are currently facing. “They often have questions about the data because it is so large,” says Marathe, who says Turner has datasets consisting of thousands of columns, and it’s not easy to understand them. “We try to help them with that,” he says.

As Turner’s Data Cloud team grows and matures, Marathe expects even more engagement from the business users’ side. “After all, we don’t really know everything that this data can be used for. That is why the self-service model is important because we just don’t know what users’ issues are and what problems they’re trying to solve,” he says. “Users will always know best.”

Lessons Learned

The main lesson Turner has absorbed from its data journey thus far is: build an infrastructure that is as flexible as possible. This means going to the cloud. Marathe also recommends keeping compute and storage completely separate, to improve your ability to manage and utilize data. “We are no longer pushing data into a traditional RDBMS [relational database management system] database and thus only able to access it from the ecosystem that supports that RDBMS,” he says. “Our data sits in an object storage such as S3 [Amazon’s Simple Storage Service], technologically speaking, which gives us the ability to move quickly to newer data access products and does not keep us tied to, for example, one DBMS.”

Marathe is a cautiously enthusiastic advocate of open source technology. “Even though we are using open source technology, we are not using it directly. Our cloud platform vendor—Qubole—is baking open source technology into its unified product, and then exposing it to us,” he says. The issue with doing things that way, he points out, is that you might not be able to move as quickly on what is out there in the open source world because you need to wait for your vendor to release its product. But the advantage is that Turner is not in the Wild Wild West. “We don’t have to figure everything out. The open source technology gets baked in and it works together as a product. And, we don’t want to necessarily move that fast anyway for security reasons,” says Marathe. Turner is therefore a “conservative” user of open source technology.

Looking back on his data journey thus far, Marathe says Turner is progressing “bit by bit.” “We’ve gone beyond simple reporting to analytics, and we do a certain amount of machine learning and artificial intelligence, but we’re not doing predictive or prescriptive analytics as much as I would have liked” Marathe anticipates doing so in the next few years.

Turner will be able to tell, for example, based on the content a customer has consumed in the past, what that customer will be interested in consuming in the future. “We already do that, of course, because we know your areas of interest. But that is still very preliminary. It’s not really deep learning at this point,” he says. After all, content has many different aspects. A particular viewer could be attracted by the theme of the movie or by the actor playing the main hero or heroine of the plot. So, many different variables exist. Figuring out what is relevant and what is not is where deep learning will come into play, Marathe says.

Turner’s use of data will continue to evolve. “We definitely need to keep on top of it. If we don’t do it, our competitors will,” says Marathe. “So, there are no other options other than being a data-driven company. If we don’t do this, we perish.”

Get Creating a Data-Driven Enterprise in Media now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.