Chapter 10. Software Above the Level of a Single Device: The Implications

The following document is adapted from the keynote address by Tim O’Reilly, Software Above the Level of a Single Device: The Implications, given at the Solid 2014 conference. Follow along to learn how you can best take advantage of new technology known as the Internet of Things.

There is some pretty amazing stuff we are seeing here at the Solid 2014 Conference. I want to give you a little bit of perspective, though.

One of my favorite quotes is this one from Edwin Schlossberg. If you’ve heard me talk, you’ve heard it before: “The skill of writing is to create a context in which other people can think.”

And that means that the way we talk about things is a kind of map. And like any map, it can either take us to the right place, or it can lead us astray. I want to talk a little bit about some of the words that we use in the current context and start thinking about what we might be missing.

I did a word cloud of the Internet of Things article on Wikipedia and as you can see, things is a really big word in the cloud, and not only that but devices and objects also appear a lot. And sure enough, there are some pretty amazing smart things. That word, smart, also shows up in the word cloud.

Multiple Smart Things

Out front in the demo hall of the building, you probably saw the Taktia smart router. I’m a home craftsman, and I want one of these. I’m not as good as I’d like to be, and this thing would make me better. It’s a human augmentation, and it is super awesome.

The Onewheel: I tried it yesterday, not very well, but it is also pretty awesome.

And of course the Makani airborne wind turbines use incredible smart control to generate power. This is an invention originally made by my son-in-law, Saul Griffith, so I’m very proud of that.

Importance of Human Input

There is something missing in this word cloud, because we shouldn’t just be talking about smart things. People and time are also concepts in there. But they are way, way too small. I think one of the things I’d like to have as an outcome of this talk is that the people in this room go read that Wikipedia entry and make it better, because I really don’t think it actually captures so many of the concepts that we need to be thinking about today.

I want to talk a little bit about these aspects of people and time that are too small in that graph.

When we think of the Internet of Smart Things, we tend to imagine that these things—the Nest thermostat or the Google self-driving car—they’re sensor and data driven, they are autonomous, not really needing human input, and they are operating in real time. That is really our first blush imagination.

But in fact, one of the super interesting things about the Google self-driving car is its connection to the human-driven Google street view vehicle that did all of the initial mapping. What you see here is actually humans and machines operating together in a complex pattern in which data is captured through human activity, stored in the cloud, pre-processed, and then used by a robot.

And I think that pattern is a really, really important one to pay attention to as you design applications. Think about how data, generated by humans, is captured over time and is stored and acted upon later by a device. It is not all real time.

Implicit Versus Explicit Input

The human input is critical, and it may also be implicit rather than explicit. So, when you see the web page for the Nest learning thermostat, the whole pitch is that it learns implicitly from you, but it also learns explicitly: you set the temperature. (By the way, Nest, you really need to use energy-friendly temperatures in your advertisements!)

The Nest auto-detects when you’ve been away for awhile and turns off the heat or air conditioning. Okay, that’s sort of our image of the smart thing, but we have to remember that we are still giving that input, it’s just through a different kind of interface. We are so used to talking about how we give input through a keyboard. Then we are giving input through a mouse and now we are giving it through a touch screen. And now, we say “Wow! When we don’t show up in the room, that is user input to this device.” It is still user input!

Think of this as a user experience problem and not an autonomous device problem. And of course you have multiple input modalities, since you have a Nest app. And one of the things I’ve noticed is that once I set the schedule using this app, the device doesn’t seem to learn any more. The interaction between the explicit, the implicit, and what modes of implicit really matter.

Types of Sensors

Think a little bit more broadly about the kinds of sensors that you have. When sensors first appear, we don’t use them that often, and as a result they still seem magical. And then we take them for granted, until someone figures out a new way to make them more powerful. Some of the most important sensors that we have that are now entering this rediscovery phase are the camera and the microphone in our phones. Both Siri and Google Now are using the microphone as the key to very, very powerful new interfaces, and ones that are going to get better very rapidly. They are going to be a big part of the user interface mix for this Internet of Things.

The point is that sensors allow us to create new kinds of user interfaces. But you still need to remember that it is a user interface.

The System as a User Interface

I do have an example of a bad user interface. And that is this wonderful smart key for my Tesla. And it does wonderful things. I walk up to my car and the car automatically opens. I don’t have to stick it in a tiny slot or turn it, or any of those things we were so used to in the mechanical age.

But it’s got one really bad flaw, which is all over the forums, which is you can’t hang it on a key ring. That’s actually a stupid device, because it didn’t think about how I might want to use it. And any time I leave my car in valet at the airport it comes back in a little plastic bag because they can’t hang it on the hook. Sometimes they lose it. The entire system in which we operate is the user interface.

There’s this great sticker that was given to me by Liam Maxwell, who is the CTO of the British government.

They’ve really focused hard on this idea: what is the user need? And, they made that the first of their design principles, to start with needs.

As we design this new world we need to think about user needs first.

A Network of Devices

Coming back to this Internet of Things word cloud, I want to move on and pick out one of the big words that we use, and that is Internet. And the Internet really matters. When you look at that smart device, it’s not a standalone device. Yes, it’s controlled by its smartphone, and yes, Nest now offers other devices connected to the network with the thermostat as its hub, and they talk to each other. In fact, all of these things are connected to satellites and data centers, and potentially to other similar devices or other smart devices.

And, by the way, even in that data center, you actually have smart networks of things. The cooling is actually controlled semi-autonomously. So there is this big network all over. There’s a network of data centers all over the world, so the Internet is clearly very involved. But let’s remember the original ground rules of the Internet.

The Robustness Principle

We used to call the Internet “The Network of Networks,” because it was this magical thing that connected all of these incompatible networks. And interoperability was the focus. One of the things I worry about as we move into this new world is that we may have forgotten that interoperability. We have vendors who are trying to own it all, building systems that talk to their devices, but not to everyone else’s. We have to think a lot about interoperability.

And we have to think about this wonderful principle that was put out by one of the saints of the early Internet, Jon Postel. (I wonder sometimes what would have happened if he hadn’t died too young of a heart attack.) He wrote in the TCP RFC, “Be conservative in what you send, be liberal in what you accept from others.” It’s become known as the Robustness Principle.

That is such an important principle, and I want those of you who are designing devices or systems to think about interoperability and to remember if we really want it to be an Internet, as opposed to a set of Intranets, you have to think about interoperability.

Software Above the Level of a Single Device

The next thing I want to cover briefly is the notion of software above the level of a single device. This is a phrase that I got from Dave Stutz, who wrote a fabulous letter when he left Microsoft back in 2003. It was his parting advice. And it ended with the line, “Useful software written above the level of the single device will command high margins for a long time to come."

This was very, very prescient, because a lot of focus was still on the PC and even on the network; it was very small thinking. And his notion of software above the level of a single device stuck in my head. I’ve used it for years. It was part of my core Web 2.0 principles. But I want to bring it out in the example of the Uber app.

System of Interaction

Let’s not get too taken up with new wearables. Uber is a smart things app. We forget that the phone is our most widely used smart thing. This thing that we carry in our pockets is filled with sensors, and it’s filled with capabilities.

But what’s really interesting about Uber is, of course, that it doesn’t work in isolation. There’s an app for the passenger, but there’s also an app for the driver. And those two things are coordinating in real time using a kind of Internet operating system. There are various types of functions for communication, and for GPS to locate everybody, and to track progress. There is a payment and a rating system. All of these things are part of a “system of interaction.” That’s a wonderful phrase that was coined by someone at IBM.

What I want you to think about here is that once you have new UI capabilities and new augmentations of humans via sensors, you can actually start to think about things differently.

There’s a wonderful quote from Aaron Levie at Box that I saw on Twitter. He said, “Uber is the lesson in building for how the world should work, instead of optimizing for how the world does work.” That’s our opportunity with this new technology that we’ve been given.

How the World “Should” Work

We can start thinking about how the world should work, instead of optimizing how the world does work. So, back to the Makani wind turbine out there. The idea is that, instead of having a turbine sitting on the ground like we’ve had since the Dutch windmills, you could actually put one in the sky using this incredible control technology. Now, they are still working on it, but the notion that this thing has to be able to fly autonomously for thousands of hours, and has to be able to take off and land by itself, and it’s generating power up high where there is always wind. That’s thinking about how the world should work, rather than how the world does work.

This notion is critical and the sensors let us do new things. A company that we are invested in at O’Reilly Alpha Tech Ventures is Cover.

Because you are registered with the cloud, and because the application is able to tell where you are, you can walk into a restaurant and sit down. You are identified, fed, and when you are done with the meal you walk out and your credit card is charged. It’s kind of magic. Because of sensors, we can rethink the way things work.

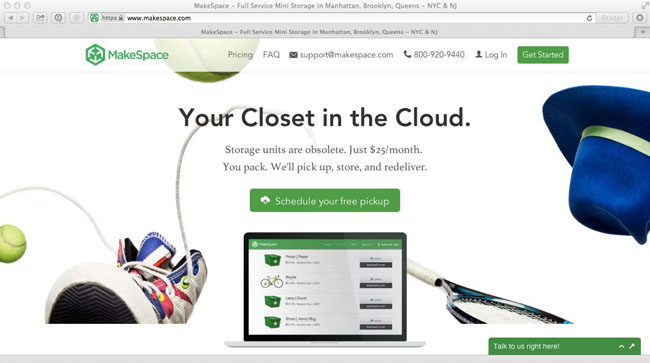

Another great example is Makespace: your closet in the cloud. This is an example of how sensors don’t have to be complicated. These guys have realized that if you can actually take pictures of what you put in the boxes when you put stuff in storage, and you can identify what’s in that box, you can put this stuff away in a warehouse where space is cheap. They can then bring you just the box you want. You don’t have to go rooting through your storage closet, because you can effectively go into a robotic warehouse. Once again, they are rethinking a familiar process, because we now have new capabilities.

Think About Things That Seem Hard

Where I want to go with this is a final piece of advice, which is don’t just try to re-create the experiences and the technologies that we have today. Try to think about new things, and in particular, think about things that seem hard—things that might have seemed impossible before you had these new capabilities.

One of the things I’m most excited about in this technology revolution is how it is giving us amazing new capabilities to affect the physical world. And the physical world, in the end, is where we all live, and where the biggest problems that we face as a society are to be found.

We have to feed the world. We have to generate energy. We have to deal with climate change. We have to deal with the problems of our society. And there are amazing new capabilities, and I want you to not just make cute, cool, and amazing consumer devices. I want you to think about hard problems that you can solve. Take this technology and make the world a better place.

Thank you.

Get Designing for the Internet of Things now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.