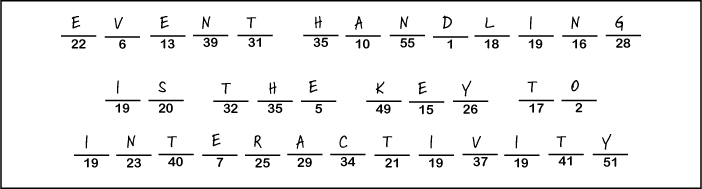

A single event handler isn’t always enough.

Sometimes you’ve got more than one event handler that needs to be called by an event. Maybe you’ve got some event-specific actions, as well as some generic code, and stuffing everything into a single event handler function won’t cut it. Or maybe you’re just trying to build clean, reusable code, and you’ve got two bits of functionality triggered by the same event. Fortunately, we can use some DOM Level 2 methods to assign multiple handler functions to a single event.

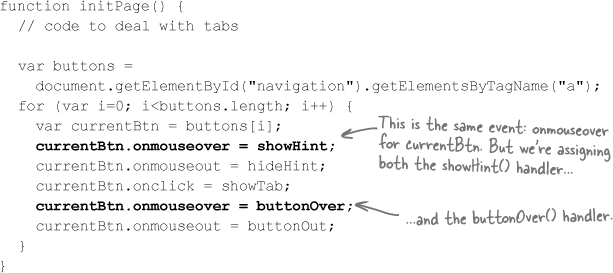

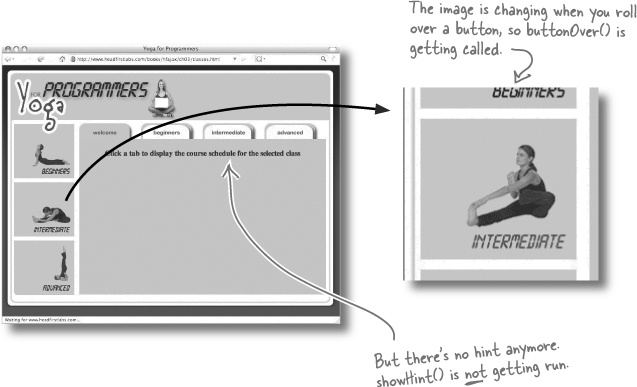

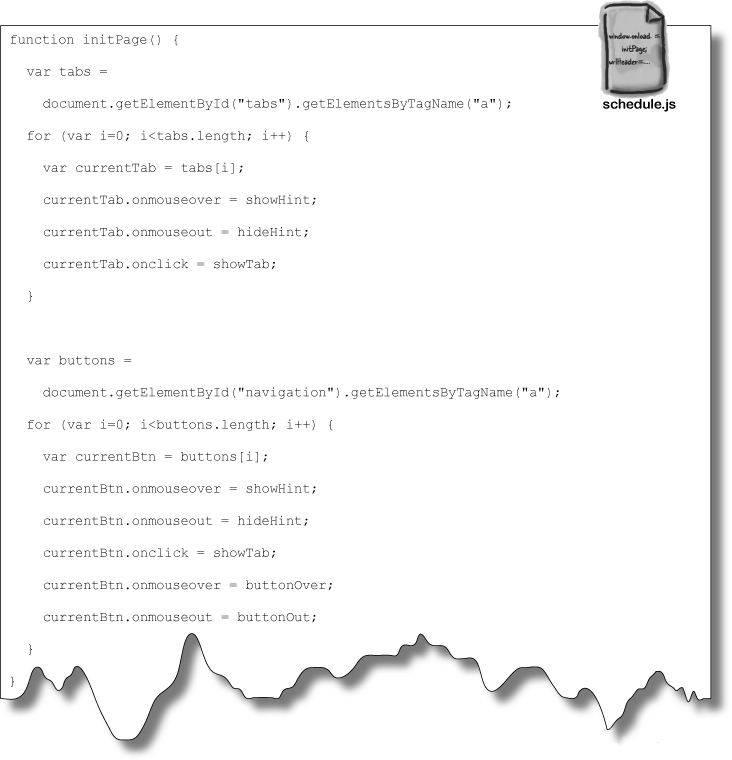

Marcy’s page has a problem. We’ve assigned two event handlers to the onmouseover property of her image buttons:

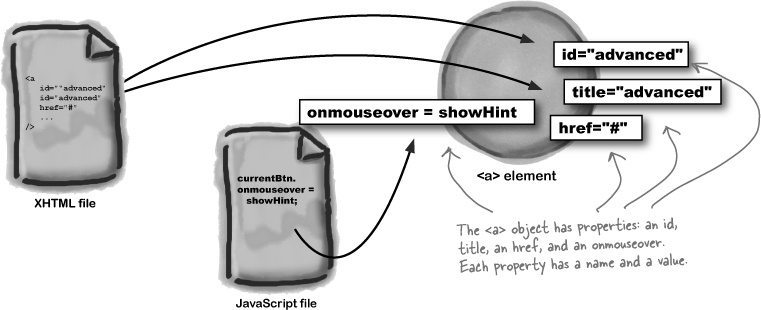

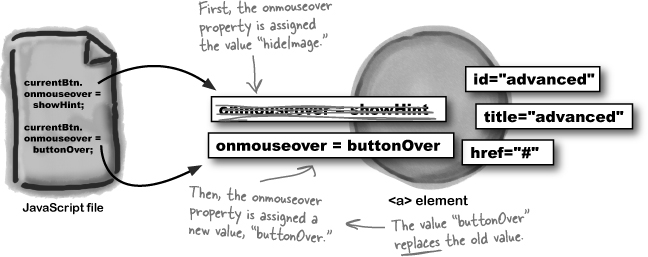

When you assign an event handler to an event on an XHTML element, the handler becomes a property of the element, just like the id or title properties of an <a> element:

If you assign a value to a property, that property has that single value. So what happens when you assign another value to that property? The property then has the new value, and the old value is gone:

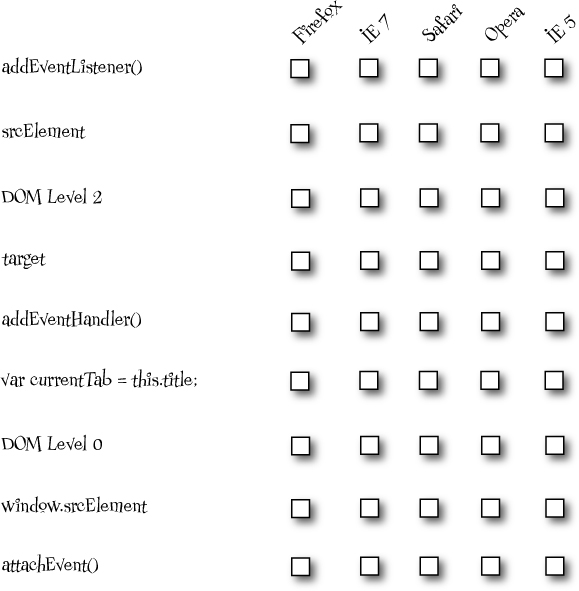

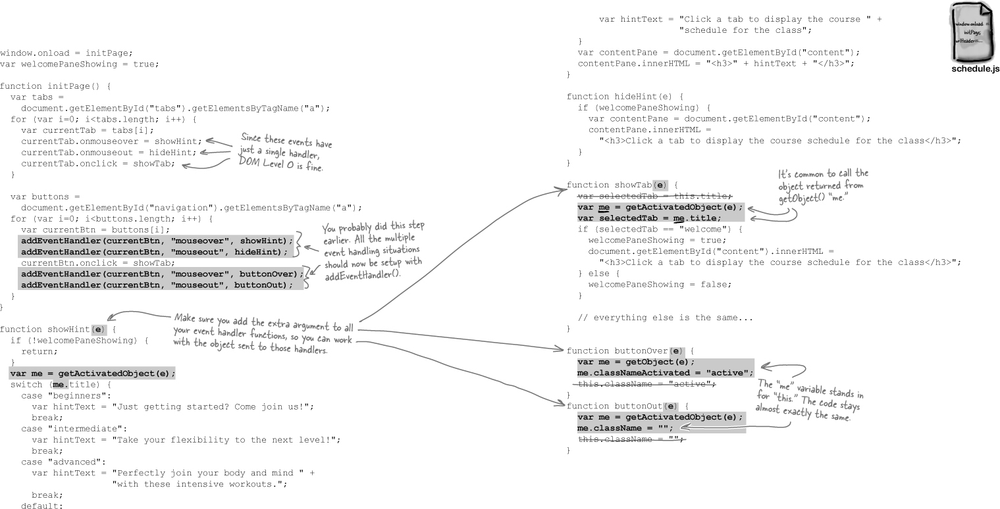

So far, we’ve been adding event handlers to elements by setting the event property directly. That’s called the DOM Level 0 model. DOM stands for the Document Object Model, and it’s how elements on a web page get turned into objects our JavaScript code can work with.

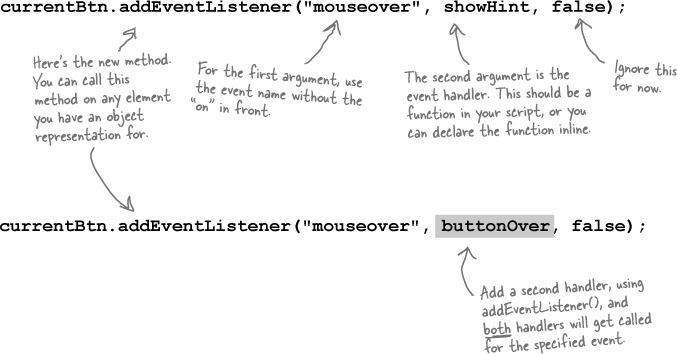

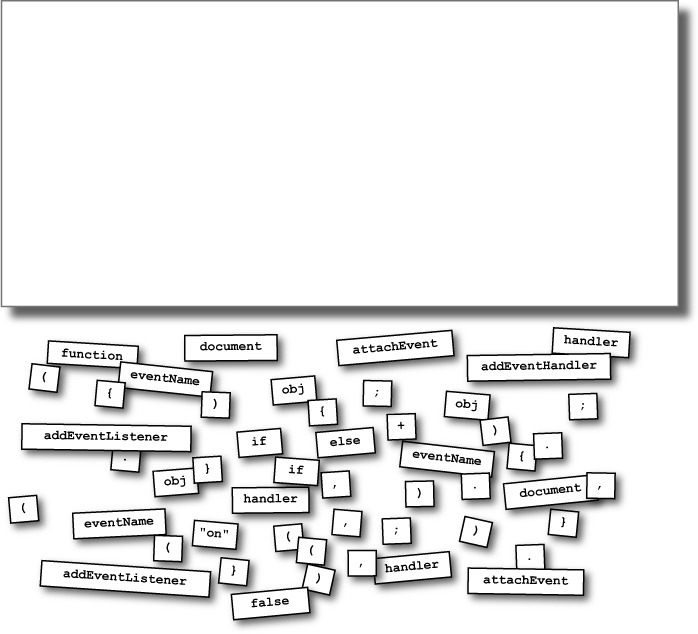

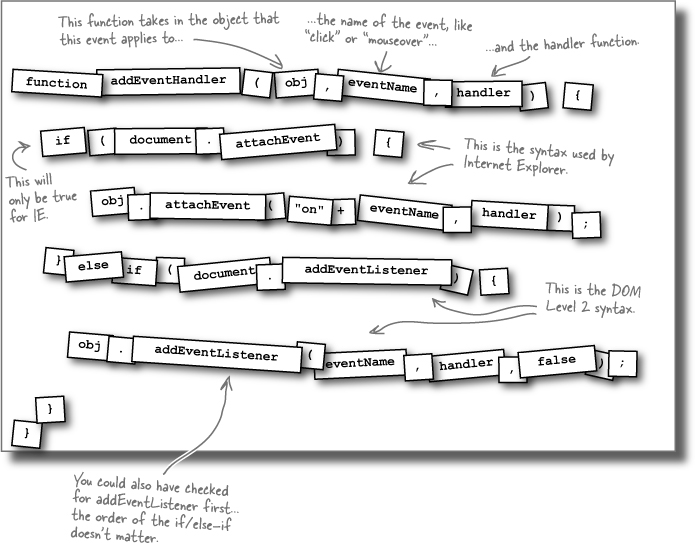

But DOM Level 0 isn’t cutting it anymore. We need a way to assign more than one handler to an event, which means we can’t just assign a handler to an event property. That’s where DOM Level 2 comes in. DOM Level 2 gives us a new method, called addEventListener(), that lets us assign more than one event handler to an event.

Here’s what the addEventListener() method looks like:

Brain Power

In what order do you think the browser will call your handlers? Do you think the ordering in which the handlers are run will affect how you write your code?

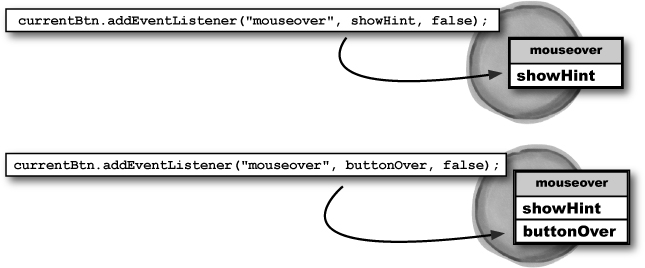

You can assign as many handlers as you want to an event using addEventListener().

addEventListener() works in any web browser that supports DOM Level 2.

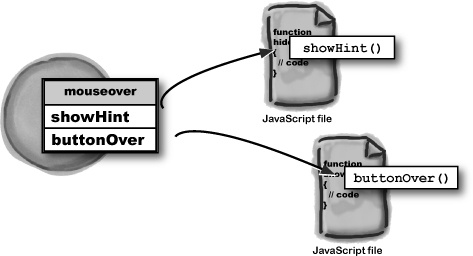

The most important thing that DOM Level 2 added to events is the ability for an event to have more than one handler registered. You’ve already seen how addEventListener() adds a handler to an event:

When an event is triggered by a mouse movement, the browser looks up the right event. Then, the browser runs every event handler function registered to that event:

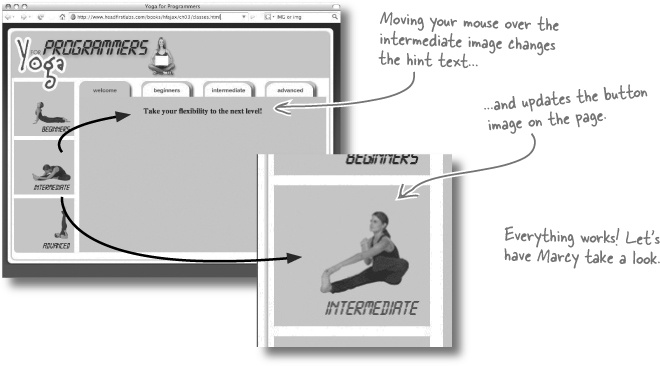

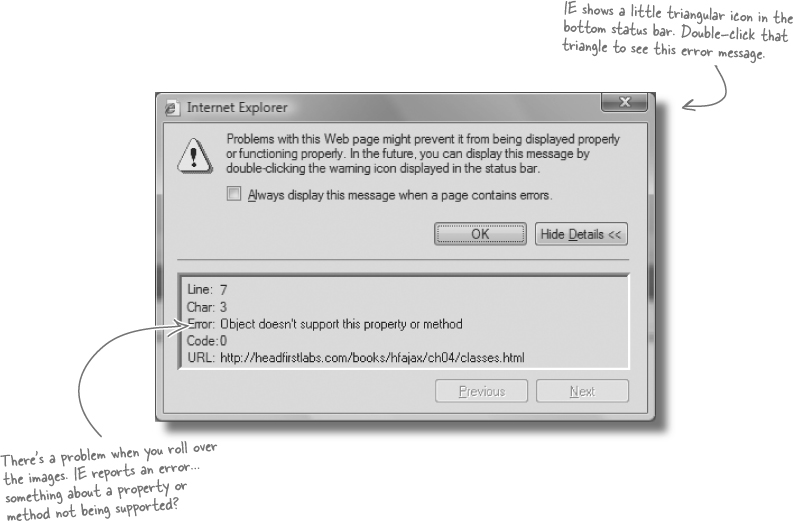

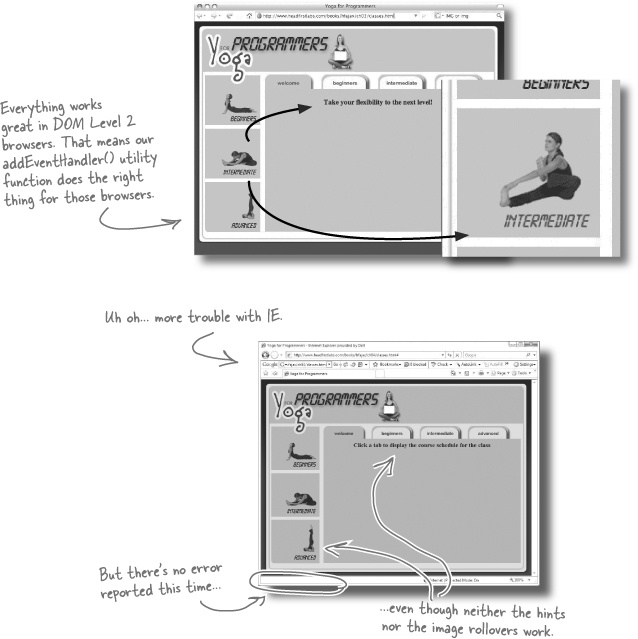

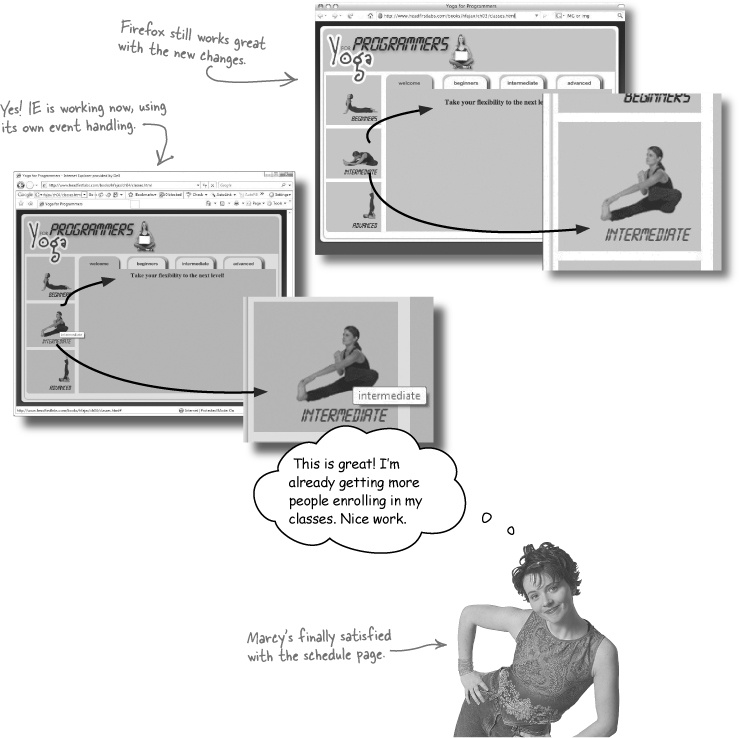

The yoga page works great on Firefox, Safari, and a lot of other browsers... but something’s definitely wrong on Internet Explorer:

You can’t control what browsers your users are working with.

It’s your job to build cross-browser applications... and always test your code in LOTS of browsers.

Remember that addEventListener() only works on browsers that support DOM Level 2? Well, Internet Explorer isn’t one of those browsers. IE has its own event model and doesn’t support addEventListener(). That’s why Marcy got an error trying the yoga page out on IE.

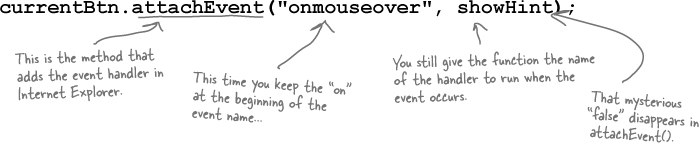

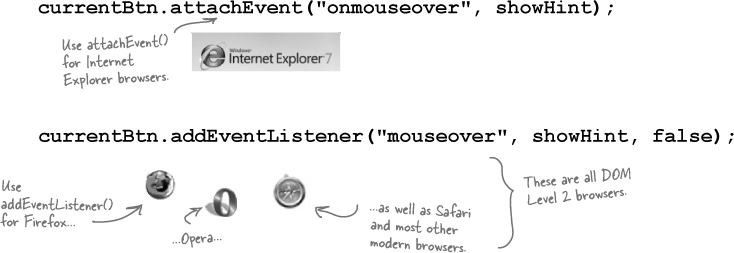

Fortunately, IE provides a method that does the same thing as addEventListener(). It’s called attachEvent():

Even though the syntax is different, these functions do exactly the same thing. So you just need to use the right one for your users’ browsers.

The browser wars are just part of web development.

Like it or not, not all browsers are the same. Besides, when Microsoft came up with their own event model, it wasn’t that obvious that the DOM Level 2 would take off like it did.

And no matter how it all happened, you can’t write off people who use IE... or those who don’t.

In IE, event names have “on” in front, for example, “onclick” and “onmouseover.”

In Firefox, Safari, and Opera, event names DON’T have “on” in front: “click” and “mouseover.”

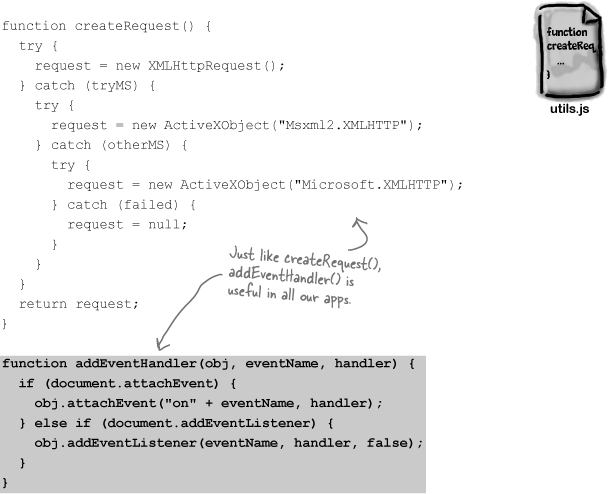

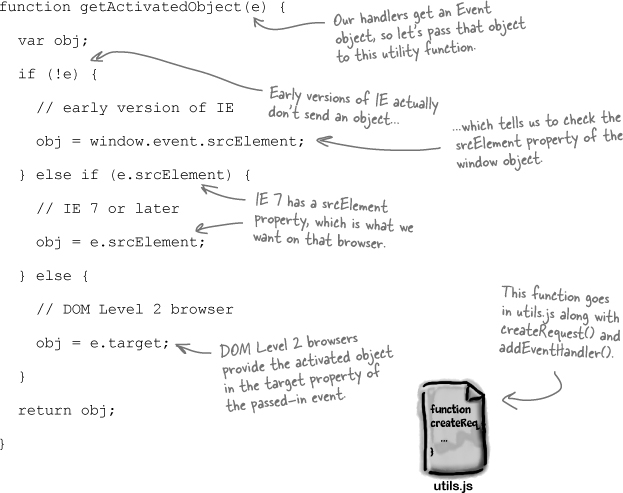

So where should you put your code for addEventHandler()? We’ll use it in Marcy’s yoga page, but it’s really a utility function. It will work for all our apps and in any browser. So go ahead and add your new code to utils.js, so we can reuse it in later web apps we build.

Anytime you build cross-browser utility functions, store those methods in scripts that you can easily reuse in your other web applications.

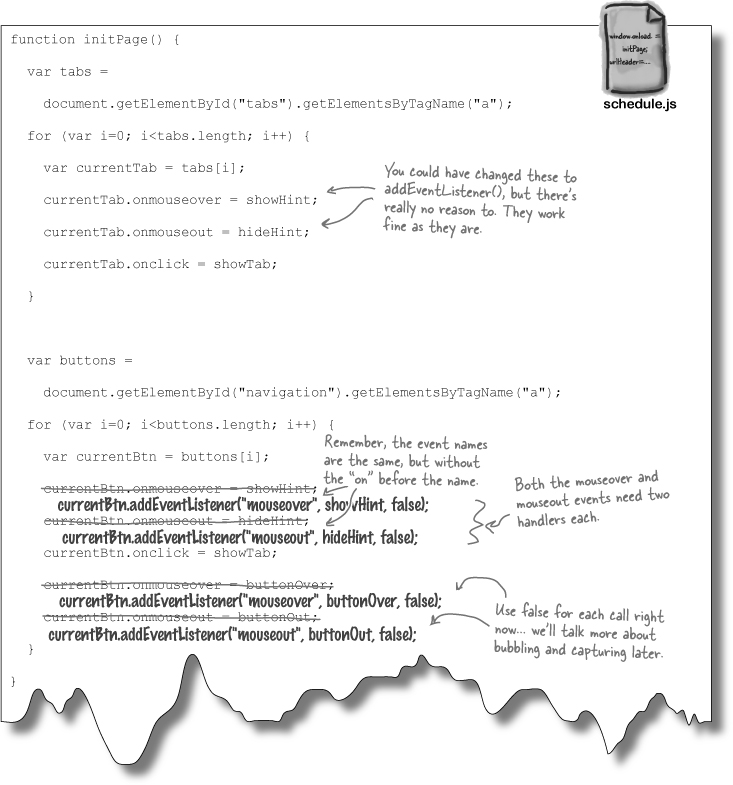

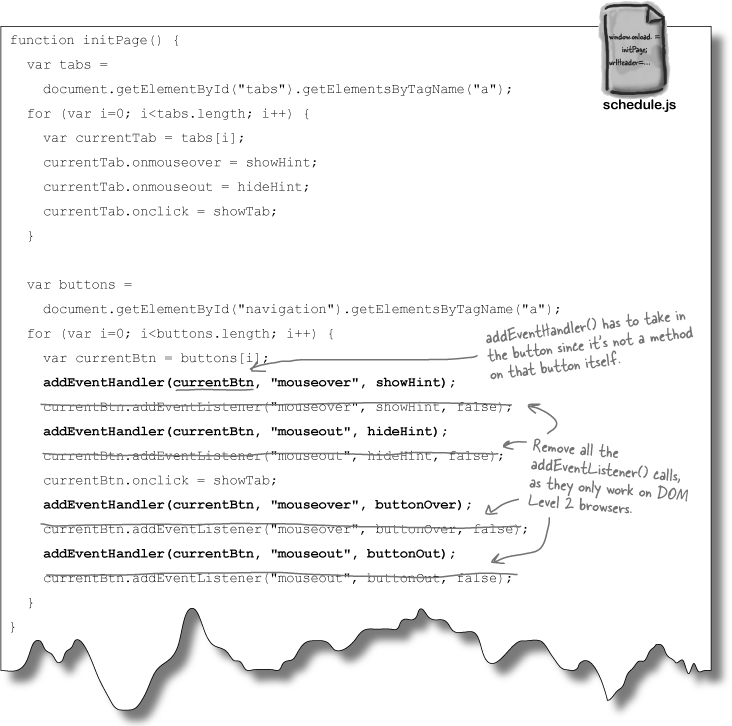

Now we need to change initPage(), in schedule.js, to use addEventHandler() instead of addEventListener(). Go ahead and make the following changes to your copy of schedule.js:

Without any error messages, it’s hard to know exactly what’s going on with Internet Explorer. Try putting in a few alert() statements in the event handlers, though, and you’ll see they’re getting called correctly.

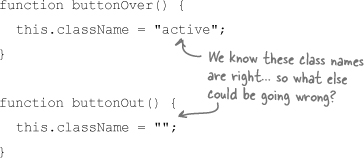

function buttonOver() {

alert("buttonOver() called.");

this.className = "active";

}

function buttonOut() {

alert("buttonOut() called.");

this.className = "";

}The event handlers are getting called, so that means that addEventHandler() is working like it should. And we’ve already seen that the code in the handlers worked before we added the rollovers. So what else could be the problem?

What do you think the problem could be? Can you figure out why the code isn’t working like it should?

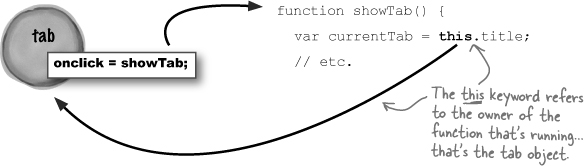

“this” refers to the owner of the executing function.

The this keyword in JavaScript always refers to the owner of the function that’s executing. So if the method bark() was called by an object called Dog, then this in bark() would refer to the Dog object.

When you assign an event handler using DOM Level 0, the element with the event is the owner. So if you did tab.onclick = showTab;, then in showTab(), this would refer to the tab element. That’s why showHint() and hideHint() worked great in the last chapter.

Note

“owner” and “caller” aren’t the same. In a web environment, the browser calls all the functions, but objects representing elements on the page are the owners of those functions.

In DOM Level 2, an event is still the owner of its handlers

When you’re using DOM Level 2 browsers like Firefox, Safari, or Opera, the event handling framework sets the owner of a handler to the object that handler is responding to an event on. So you get the same behavior as with DOM Level 1. That’s why our handlers still work with DOM Level 2 browsers.

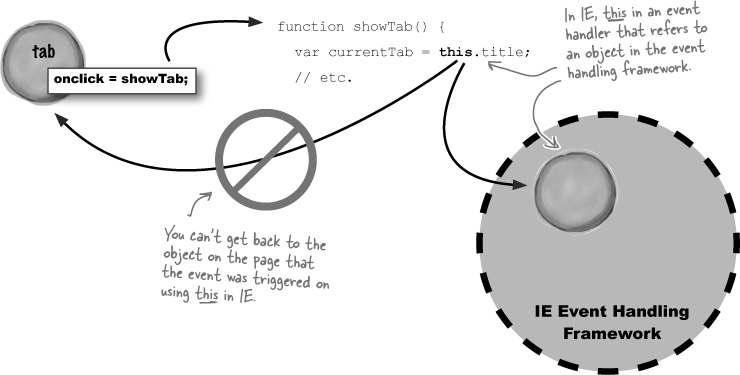

But what about IE?

You already know that IE doesn’t implement DOM Level 2. IE has its own event handling framework. So in IE, the event framework owns the handler functions, not the object on the XHTML page that was activated with a click or mouse over. In other words, this in showTab() refers to the IE event framework, not to a tab element on Marcy’s yoga web page.

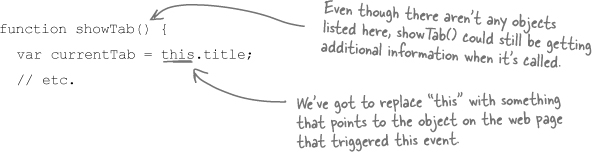

One of the cooler things about JavaScript is that you don’t need to list all the arguments that your functions take when you declare that function. So even if your function declaration is showTab(), you can pass arguments to showTab() when you call it.

The bad thing about that is sometimes you miss out on arguments that are passed to your function.

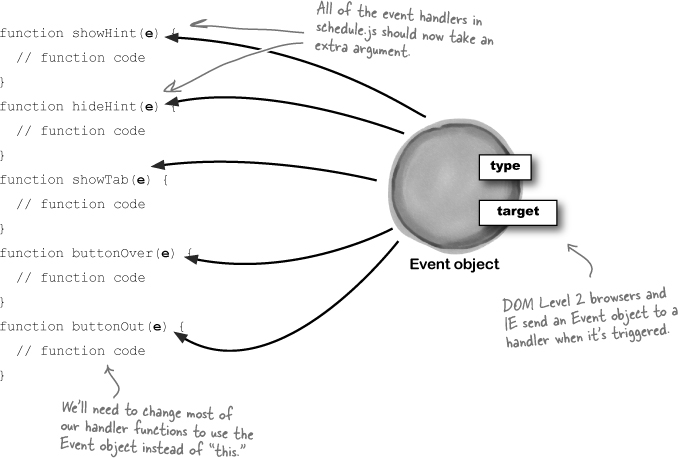

When you register an event handler using DOM Level 2 and addEventListener(), or attachEvent() and IE, both frameworks pass your event handlers an object of the Event type.

Your handlers can then use this object to figure out what object on a page was activated by an event, and which actual event was triggered.

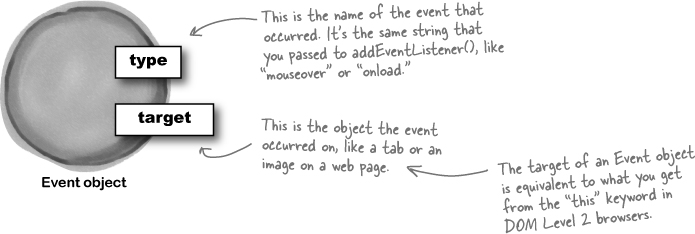

There are two properties in particular that are really helpful to know about. The first is type, which gives the name of the event that was triggered, like “mouseover” or “click.” The second is target, which gives you the target of the event: the object on the page that was activated.

Event objects know what object triggered them and what type of event they are.

You don’t have to list all the arguments a JavaScript function gets. But if you want to actually use those arguments in the function, you do need to list the arguments. First, we need to get access to the Event object in our handlers, so we can figure out what object on a page triggered a call to our handler. Then, we need to list the argument for that Event object:

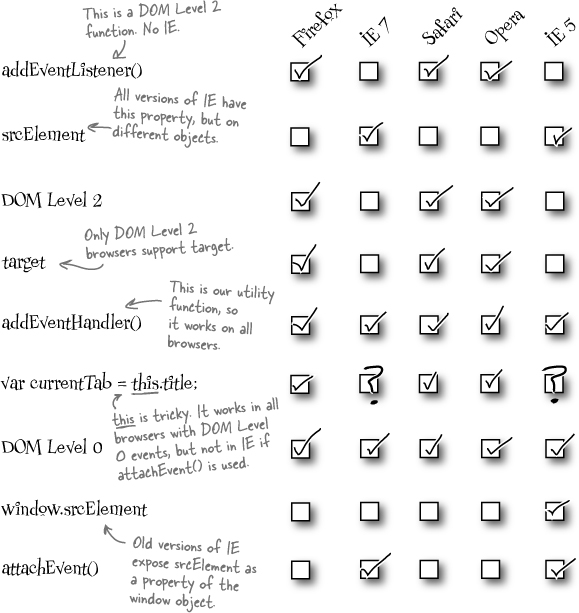

The good news is that both IE and DOM Level 2 browsers make the object that triggered an event available. The bad news is that DOM Level 2 and IE use different versions of the Event object, each with different properties.

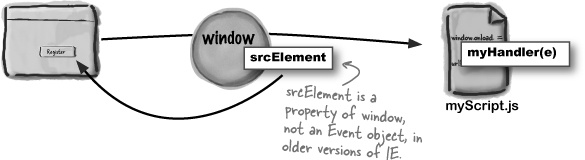

In some cases, the Event object properties refer to the same thing, but the property names are different. And to make matters worse, modern versions of IE pass in an Event object, but earlier versions of IE make the Event object available as a property of the window object.

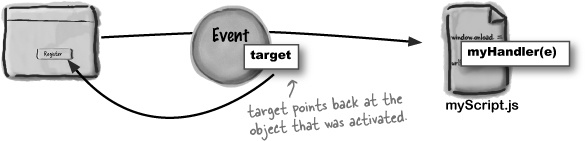

Browsers that support DOM Level 2, like Firefox, Safari, and Opera, pass an Event object to event handlers. The Event object has a property named “target” that refers to the object that triggered the event.

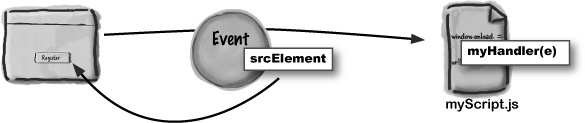

Internet Explorer 7 passes an Event object to event handlers. The Event object has a property named “srcElement” that refers to the object that triggered the event.

Earlier versions of Internet Explorer provide the object that triggered an event in a property named “srcElement,” available on the window object.

The best way to deal with differences in how IE and DOM Level 2 browsers handle events is another utility function. Our handler functions are now getting Event objects, but what we really need is the activated object: the object representation of the element on the page that the event occurred on.

So let’s build a utility function to take the event argument we get from those browsers, and figure out and return the activated object:

Get Head First Ajax now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.