How to use this Book: Intro

Who is this book for?

If you can answer “yes” to all of these:

Are you comfortable with numbers and pre-algebra?

Do you want to learn Algebra by learning the concepts and not just looking for practice problems?

Are you familiar with integers and fractions and ready to move onto solving for unknowns?

this book is for you.

Who should probably back away from this book?

If you can answer “yes” to any of these:

Are you someone who is really uncomfortable with fractions and decimals?

Who is looking for Algebra 2 or Statistics information?

Are you someone who is obsessed with plugging things into a calculator?

this book is not for you.

We know what you’re thinking

“How can this be a serious Algebra book?”

“What’s with all the graphics?”

“Can I actually learn it this way?”

We know what your brain is thinking

Your brain craves novelty. It’s always searching, scanning, waiting for something unusual. It was built that way, and it helps you stay alive.

So what does your brain do with all the routine, ordinary, normal things you encounter? Everything it can to stop them from interfering with the brain’s real job—recording things that matter. It doesn’t bother saving the boring things; they never make it past the “this is obviously not important” filter.

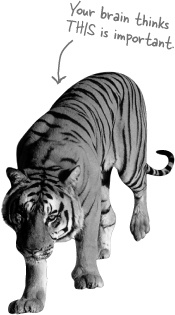

How does your brain know what’s important? Suppose you’re out for a day hike and a tiger jumps in front of you, what happens inside your head and body?

Neurons fire. Emotions crank up. Chemicals surge.

And that’s how your brain knows...

This must be important! Don’t forget it!

But imagine you’re at home, or in a library. It’s a safe, warm, tiger-free zone. You’re studying. Getting ready for an exam. Or trying to learn some tough technical topic your boss thinks will take a week, ten days at the most.

Just one problem. Your brain’s trying to do you a big favor. It’s trying to make sure that this obviously non-important content doesn’t clutter up scarce resources. Resources that are better spent storing the really big things. Like tigers. Like the danger of fire. Like remembering where all of the warp zones are in Super Mario Brothers. And there’s no simple way to tell your brain, “Hey brain, thank you very much, but no matter how dull this book is, and how little I’m registering on the emotional Richter scale right now, I really do want you to keep this stuff around.”

Metacognition: thinking about thinking

If you really want to learn, and you want to learn more quickly and more deeply, pay attention to how you pay attention. Think about how you think. Learn how you learn.

Most of us did not take courses on metacognition or learning theory when we were growing up. We were expected to learn, but rarely taught to learn.

But we assume that if you’re holding this book, you really want to master Algebra. And you probably don’t want to spend a lot of time. If you want to use what you read in this book, you need to remember what you read. And for that, you’ve got to understand it. To get the most from this book, or any book or learning experience, take responsibility for your brain. Your brain on this content.

The trick is to get your brain to see the new material you’re learning as Really Important. Crucial to your well-being. As important as a tiger. Otherwise, you’re in for a constant battle, with your brain doing its best to keep the new content from sticking.

So just how DO you get your brain to treat Algebra like it was a hungry tiger?

There’s the slow, tedious way, or the faster, more effective way. The slow way is about sheer repetition. You obviously know that you are able to learn and remember even the dullest of topics if you keep pounding the same thing into your brain. With enough repetition, your brain says, “This doesn’t feel important to him, but he keeps looking at the same thing over and over and over, so I suppose it must be.”

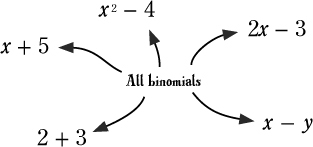

The faster way is to do anything that increases brain activity, especially different types of brain activity. The things on the previous page are a big part of the solution, and they’re all things that have been proven to help your brain work in your favor. For example, studies show that putting words within the pictures they describe (as opposed to somewhere else in the page, like a caption or in the body text) causes your brain to try to makes sense of how the words and picture relate, and this causes more neurons to fire. More neurons firing = more chances for your brain to get that this is something worth paying attention to, and possibly recording.

A conversational style helps because people tend to pay more attention when they perceive that they’re in a conversation, since they’re expected to follow along and hold up their end. The amazing thing is, your brain doesn’t necessarily care that the “conversation” is between you and a book! On the other hand, if the writing style is formal and dry, your brain perceives it the same way you experience being lectured to while sitting in a roomful of passive attendees. No need to stay awake.

But pictures and conversational style are just the beginning...

Here’s what WE did

We used pictures, because your brain is tuned for visuals, not text. As far as your brain’s concerned, a picture really is worth a thousand words. And when text and pictures work together, we embedded the text in the pictures because your brain works more effectively when the text is within the thing the text refers to, as opposed to in a caption or buried in the text somewhere.

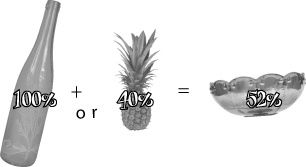

We used redundancy, saying the same thing in different ways and with different media types, and multiple senses, to increase the chance that the content gets coded into more than one area of your brain.

We used concepts and pictures in unexpected ways because your brain is tuned for novelty, and we used pictures and ideas with at least some emotional content, because your brain is tuned to pay attention to the biochemistry of emotions. That which causes you to feel something is more likely to be remembered, even if that feeling is nothing more than a little humor, surprise, or interest.

We used a personalized, conversational style, because your brain is tuned to pay more attention when it believes you’re in a conversation than if it thinks you’re passively listening to a presentation. Your brain does this even when you’re reading.

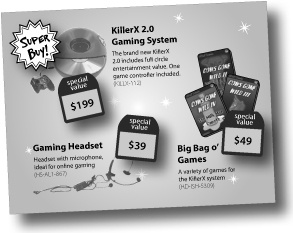

We included more than 80 activities, because your brain is tuned to learn and remember more when you do things than when you read about things. And we made the exercises challenging-yet-do-able, because that’s what most people prefer.

We used multiple learning styles, because you might prefer step-by-step procedures, while someone else wants to understand the big picture first, and someone else just wants to see an example. But regardless of your own learning preference, everyone benefits from seeing the same content represented in multiple ways.

We include content for both sides of your brain, because the more of your brain you engage, the more likely you are to learn and remember, and the longer you can stay focused. Since working one side of the brain often means giving the other side a chance to rest, you can be more productive at learning for a longer period of time.

And we included stories and exercises that present more than one point of view, because your brain is tuned to learn more deeply when it’s forced to make evaluations and judgments.

We included challenges, with exercises, and by asking questions that don’t always have a straight answer, because your brain is tuned to learn and remember when it has to work at something. Think about it—you can’t get your body in shape just by watching people at the gym. But we did our best to make sure that when you’re working hard, it’s on the right things. That you’re not spending one extra dendrite processing a hard-to-understand example, or parsing difficult, jargon-laden, or overly terse text.

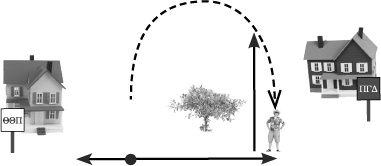

We used people. In stories, examples, pictures, etc., because, well, because you’re a person. And your brain pays more attention to people than it does to things.

Here’s what YOU can do to bend your brain into submission

So, we did our part. The rest is up to you. These tips are a starting point; listen to your brain and figure out what works for you and what doesn’t. Try new things.

Slow down. The more you understand, the less you have to memorize.

Don’t just read. Stop and think. When the book asks you a question, don’t just skip to the answer. Imagine that someone really is asking the question. The more deeply you force your brain to think, the better chance you have of learning and remembering.

Do the exercises. Write your own notes.

We put them in, but if we did them for you, that would be like having someone else do your workouts for you. And don’t just look at the exercises. Use a pencil. There’s plenty of evidence that physical activity while learning can increase the learning.

Read the “There are No Dumb Questions”

That means all of them. They’re not optional sidebars, they’re part of the core content! Don’t skip them.

Make this the last thing you read before bed. Or at least the last challenging thing.

Part of the learning (especially the transfer to long-term memory) happens after you put the book down. Your brain needs time on its own, to do more processing. If you put in something new during that processing time, some of what you just learned will be lost.

Talk about it. Out loud.

Speaking activates a different part of the brain. If you’re trying to understand something, or increase your chance of remembering it later, say it out loud. Better still, try to explain it out loud to someone else. You’ll learn more quickly, and you might uncover ideas you hadn’t known were there when you were reading about it.

Drink water. Lots of it.

Your brain works best in a nice bath of fluid. Dehydration (which can happen before you ever feel thirsty) decreases cognitive function.

Listen to your brain.

Pay attention to whether your brain is getting overloaded. If you find yourself starting to skim the surface or forget what you just read, it’s time for a break. Once you go past a certain point, you won’t learn faster by trying to shove more in, and you might even hurt the process.

Feel something.

Your brain needs to know that this matters. Get involved with the stories. Make up your own captions for the photos. Groaning over a bad joke is still better than feeling nothing at all.

Use Algebra in the Real World.

There’s only one way to get comfortable with Algebra: do it a lot. Now, that doesn’t mean you need to lock yourself in a room with graph paper and pencils. But it does mean you should think about how Algebra fits in to the world around you. What problem are you trying to solve? What are the knowns and unknowns? How do they relate to each other? The point is that you won’t really get Algebra if you just read about it—you need to do it. We’re going to give you a lot of practice: every chapter is full of exercises and asks questions that you need to think about. Don’t just skip over them—most of the learning actually happens when you work on the exercises. Don’t be afraid to peek at the solutions if you get stuck, but at least give the problems a try first.

Read Me

This is a learning experience, not a reference book. We deliberately stripped out everything that might get in the way of learning whatever it is we’re working on at that point in the book. And the first time through, you need to begin at the beginning because the book makes assumptions about what you’ve already seen and learned.

We start off by teaching how to solve algebraic equations.

Believe it or not, even if you’ve never taken Algebra, you can jump right in and start solving for unknowns. You’ll also learn about the deeper motivations for the study of Algebra, and why you should learn it in the first place.

Calculators are only for arithmetic you can’t solve easily, NOT for solving equations.

There are lots of calculators out there that can do lots of things, including solving equations and plotting graphs. Since the entire purpose of working through this book is to learn how to solve and graph equations yourself, using a calculator to do it would just cheat you out of your learning experience!

If you’re rusty on some pre-Algebra topics, we can help.

You need to be able to work with fractions, decimals, integers, and exponents to get into Algebra and solve for unknowns. The good news is that if you have a decent understanding of these concepts, but you can’t quite remember how to get a common denominator, there is a big appendix at the back to help you. It’s quick and dirty, but it can bring you back up to speed on how to work with those tricky pre-Algebra topics.

Algebra is not just about getting the right “answer.”

There’s a lot in this book about the process: writing out the steps, understanding what’s going on at each point, and really understanding what you’re doing. We have taken a lot of time to make sure that each exercise is well explained, and there’s a reason for it—you’re trying to learn here, right? So don’t just skip to the x = 5 and see if you’re right, because that’s only a piece of the answer.

The activities are NOT optional.

The exercises and activities are not add-ons; they’re part of the core content of the book. Some of them are to help with memory, some are for understanding, and some will help you apply what you’ve learned. Don’t skip the exercises.

The redundancy is intentional and important.

One distinct difference in a Head First book is that we want you to really get it. And once you finish the book, we want you to remember what you’ve learned. Most reference books don’t have retention and recall as a goal, but this book is about learning, so you’ll see some of the same concepts come up more than once.

Everyone can learn Algebra, even if you think you’re not a “math person.”

You need to leave all of this “I’m not a math person” stuff behind. Everybody is a “math person,” you just might not know it yet. You actually do a lot of Algebra every day, it’s just not labelled that way. If you haven’t yet found your inner “math person,” or you’re rusty, you’ve come to the right place. You’re going to finish the book knowing how to handle Algebra. Now get going and solve some equations!

The technical review team

Technical Reviewers:

Ariana Anderson is a PhD Candidate in Statistics at UCLA and a member of the Collegium of University Teaching Fellows. Her research involves the integration of neuro-imaging and statistics to create “mind reading” machines.

Amanda Borcky is a student at Virginia Tech in Blacksburg, VA. She is studying Dietetics and hopes to practice Clinical Dieteics in the future. This is her first time technically reviewing a book.

Dawn Griffiths is the author of Head First Statistics. When Dawn’s not working on Head First books, you’ll find her honing her Tai Chi skills, making bobbin lace, or spending time with her lovely husband David.

Karen Shaner is a grad student at Emerson College in Boston pursuing a MA in Publishing and Writing in addition to working at O’Reilly. In the little free time she has, she enjoys contra dancing, spending time with friends, singing with the Praise Band, and enjoying all that Boston has to offer.

Shannon Stewart is a former fifth grade math teacher. During her five years in Mesquite, she was grade level chair as well as recognized in Who’s Who of American Teachers. She graduated from Hardin Simmons with a BS in elementary education and then went on to graduate cum laude from A&M Commerce with a Masters in Education. She currently resides in Texas with her husband Les and her son Nathan.

Herbert Tracey received his BS from Towson University and a MS from The Johns Hopkins University. Currently, he is an instructor of Mathematical Sciences at Loyola University Maryland and served as Department Chair of Mathematics (retired) at Hereford High School.

Cary Collett majored in physics and astrophysics in college and grad school, respectively, so needless to say, he learned a great deal of mathematics and will tell anyone that algebra is the hardest subject in the field. He current works in IT and lives in central Ohio.

Acknowledgments

Our editors:

Thanks to Sanders Kleinfeld, who took this book from the first outline through the first draft. He also put up with endless questions (mostly from Tracey), and let us wax philosophical about the math books that 80’s TV stars write.

And to Brett McLaughlin, who in addition to running the whole series, got us from the first draft across the finish line. His feedback had a whole lot of “why didn’t we think of that” in it, which was incredibly helpful. His understanding about the kids and dog in the background on conference calls was also a plus.

Thanks also to Lou Barr, who somehow managed to take notes that say things like “Lou, can you make this look cool?” and made things look cool. Since neither of us have any artistic talent at all, anything that looks fantastic is clearly her work.

The O’Reilly team:

To Caitrin McCullough, for the cool website and Karen Shaner, for being both a tech reviewer and keeping the review process running smoothly.

To Brittany Smith, the book’s Production Editor, who always answered questions really fast, somehow made sense of all of the computer files that went into this thing, and always sent happy emails.

Last but not least, to Laurie Petrycki, who gave us a chance to write a math book that we’re very excited about!

To the reviewers:

Thanks to all of you for reading the whole book with such enthusiasm. To Amanda Borcky, for being our sample audience and telling us when we were not being cool. To Herbert Tracey, who, in addition to teaching Tracey Trig and Calculus, also gave us extremely detailed feedback that made this a much better math book. To Ariana Anderson and Shannon Stewart, who, as math teachers, could point out gaps in our assumptions and good questions to ask. Finally, to Cary Collett and Dawn Griffiths, who helped with the math and made sure that we were keeping true to the Head First way.

To our friends and family:

To all of the Pilones and all of the Chadwicks, if it hadn’t been for your love and support, we wouldn’t have passed Algebra the first time! To Tracey’s math teachers—Mr. Tracey, Mrs. Vesley, and Mrs. Booth—who turned her from a being math hater into an engineer; and to Dan’s math teachers—Br. Leahy, Mr. Cleary, Fr. Shea, and Mrs. Newell—you saw past him getting his head stuck in the door and put the first draft of this book in motion so many years ago....

And last but not least, thanks to Vinny and Nick—the first two projects that Dan and Tracey worked on together—who put up with a lot of “Daddy and Mommy have a call” and learned more Algebra than any preschooler or kindergartner should know.

Safari® Books Online

When you see a Safari® icon on the cover of your favorite technology book that means the book is available online through the O’Reilly Network Safari Bookshelf.

Safari offers a solution that’s better than e-books. It’s a

virtual library that lets you easily search thousands of top tech books,

cut and paste code samples, download chapters, and find quick answers

when you need the most accurate, current information. Try it for free at

http://safari.oreilly.com.

Get Head First Algebra now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.