Chapter 1. let’s get going: Syntax Basics

Are you ready to turbo-charge your software? Do you want a simple programming language that compiles fast? That runs fast? That makes it easy to distribute your work to users? Then you’re ready for Go!

Go is a programming language that focuses on simplicity and speed. It’s simpler than other languages, so it’s quicker to learn. And it lets you harness the power of today’s multicore computer processors, so your programs run faster. This chapter will show you all the Go features that will make your life as a developer easier, and make your users happier.

Ready, set, Go!

Back in 2007, the search engine Google had a problem. They had to maintain programs with millions of lines of code. Before they could test new changes, they had to compile the code into a runnable form, a process which at the time took the better part of an hour. Needless to say, this was bad for developer productivity.

So Google engineers Robert Griesemer, Rob Pike, and Ken Thompson sketched out some goals for a new language:

Fast compilation

Less cumbersome code

Unused memory freed automatically (garbage collection)

Easy-to-write software that does several operations simultaneously (concurrency)

Good support for processors with multiple cores

After a couple years of work, Google had created Go: a language that was fast to write code for and produced programs that were fast to compile and run. The project switched to an open source license in 2009. It’s now free for anyone to use. And you should use it! Go is rapidly gaining popularity thanks to its simplicity and power.

If you’re writing a command-line tool, Go can produce executable files for Windows, macOS, and Linux, all from the same source code. If you’re writing a web server, it can help you handle many users connecting at once. And no matter what you’re writing, it will help you ensure that your code is easier to maintain and add to.

Ready to learn more? Let’s Go!

The Go Playground

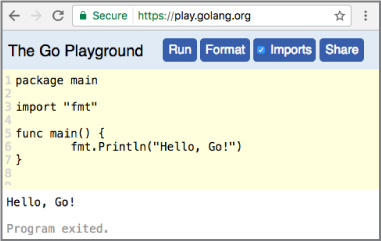

The easiest way to try Go is to visit https://play.golang.org in your web browser. There, the Go team has set up a simple editor where you can enter Go code and run it on their servers. The result is displayed right there in your browser.

(Of course, this only works if you have a stable internet connection. If you don’t, see “Installing Go on your computer” to learn how to download and run the Go compiler directly on your computer. Then run the following examples using the compiler instead.)

Let’s try it out now!

Open https://play.golang.org in your browser. (Don’t worry if what you see doesn’t quite match the screenshot; it just means they’ve improved the site since this book was printed!)

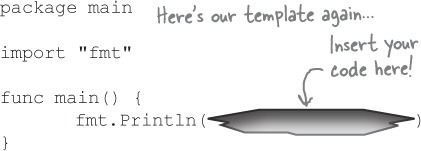

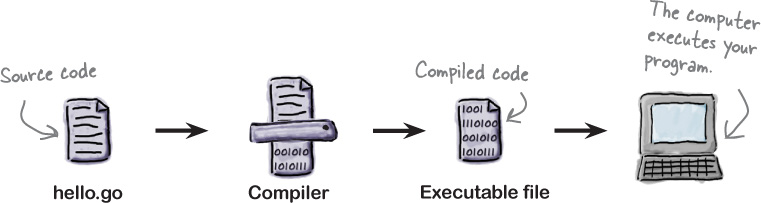

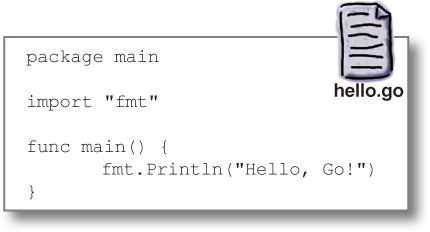

Delete any code that’s in the editing area, and type this instead:

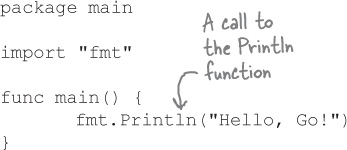

package main import "fmt" func main() { fmt.Println("Hello, Go!") }Note

Don’t worry, we’ll explain what all this means on the next page!

Click the Format button, which will automatically reformat your code according to Go conventions.

Click the Run button.

You should see “Hello, Go!” displayed at the bottom of the screen. Congratulations, you’ve just run your first Go program!

Turn the page, and we’ll explain what we just did...

What does it all mean?

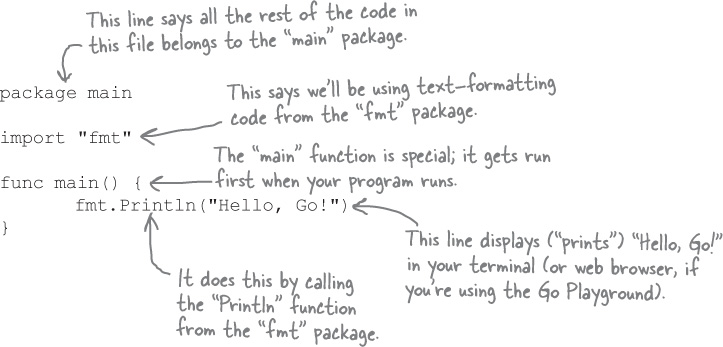

You’ve just run your first Go program! Now let’s look at the code and figure out what it actually means...

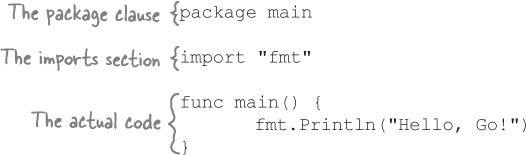

Every Go file starts with a package clause. A package is a collection of code that all does similar things, like formatting strings or drawing images. The package clause gives the name of the package that this file’s code will become a part of. In this case, we use the special package main, which is required if this code is going to be run directly (usually from the terminal).

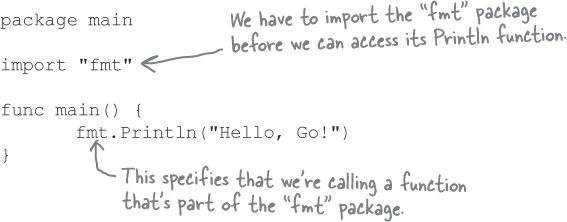

Next, Go files almost always have one or more import statements. Each file needs to import other packages before its code can use the code those other packages contain. Loading all the Go code on your computer at once would result in a big, slow program, so instead you specify only the packages you need by importing them.

The last part of every Go file is the actual code, which is often split up into one or more functions. A function is a group of one or more lines of code that you can call (run) from other places in your program. When a Go program is run, it looks for a function named main and runs that first, which is why we named this function main.

The typical Go file layout

You’ll quickly get used to seeing these three sections, in this order, in almost every Go file you work with:

The package clause

Any

importstatementsThe actual code

The saying goes, “a place for everything, and everything in its place.” Go is a very consistent language. This is a good thing: you’ll often find you just know where to look in your project for a given piece of code, without having to think about it!

there are no Dumb Questions

Q: My other programming language requires that each statement end with a semicolon. Doesn’t Go?

A: You can use semicolons to separate statements in Go, but it’s not required (in fact, it’s generally frowned upon).

Q: What’s this Format button? Why did we click that before running our code?

A: The Go compiler comes with a standard formatting tool, called go fmt. The Format button is the web version of go fmt.

Whenever you share your code, other Go developers will expect it to be in the standard Go format. That means that things like indentation and spacing will be formatted in a standard way, making it easier for everyone to read. Where other languages achieve this by relying on people manually reformatting their code to conform to a style guide, with Go all you have to do is run go fmt, and it will automatically fix everything for you.

We ran the formatter on every example we created for this book, and you should run it on all your code, too!

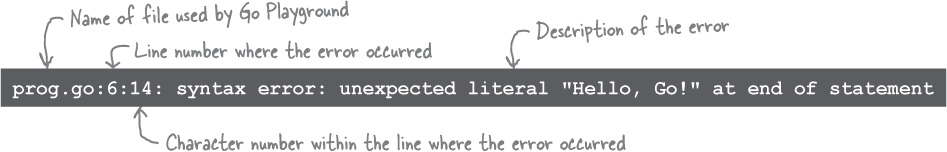

What if something goes wrong?

Go programs have to follow certain rules to avoid confusing the compiler. If we break one of these rules, we’ll get an error message.

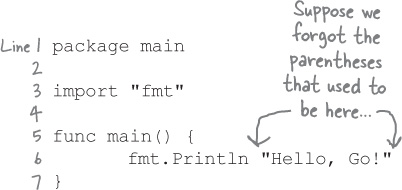

Suppose we forgot to add parentheses on our call to the Println function on line 6.

If we try to run this version of the program, we get an error:

Go tells us which source code file and line number we need to go to so we can fix the problem. (The Go Playground saves your code to a temporary file before running it, which is where the prog.go filename comes from.) Then it gives a description of the error. In this case, because we deleted the parentheses, Go can’t tell we’re trying to call the Println function, so it can’t understand why we’re putting "Hello, Go" at the end of line 6.

Breaking Stuff is Educational!

We can get a feel for the rules Go programs have to follow by intentionally breaking our program in various ways. Take this code sample, try making one of the changes below, and run it. Then undo your change and try the next one. See what happens!

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

fmt.Println("Hello, Go!")}

Note

Try breaking our code sample and see what happens!

| If you do this... | ...it will fail because... |

|---|---|

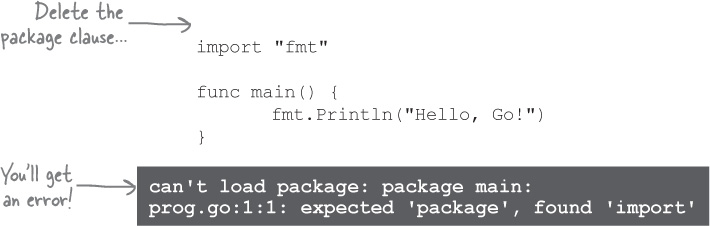

Delete the package clause... package main |

Every Go file has to begin with a package clause. |

Delete the import statement... import "fmt" |

Every Go file has to import every package it references. |

Import a second (unused) package... import "fmt" |

Go files must import only the packages they reference. (This helps keep your code compiling fast!) |

Rename the main function... func |

Go looks for a function named main to run first. |

Change the Println call to lowercase... fmt. |

Everything in Go is case-sensitive, so although fmt.Println is valid, there’s no such thing as fmt.println. |

Delete the package name before Println... |

The Println function isn’t part of the main package, so Go needs the package name before the function call. |

Let’s try the first one as an example...

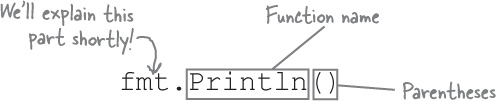

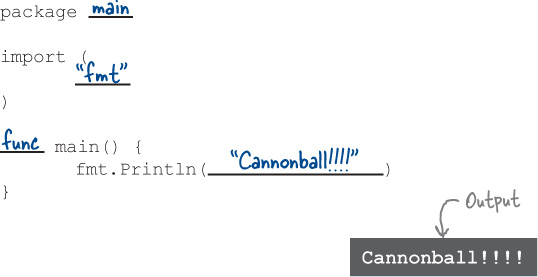

Calling functions

Our example includes a call to the fmt package’s Println function. To call a function, type the function name (Println in this case), and a pair of parentheses.

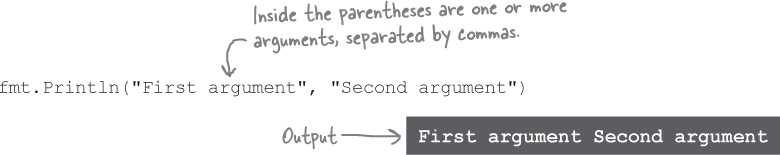

Like many functions, Println can take one or more arguments: values you want the function to work with. The arguments appear in parentheses after the function name.

Println can be called with no arguments, or you can provide several arguments. When we look at other functions later, however, you’ll find that most require a specific number of arguments. If you provide too few or too many, you’ll get an error message saying how many arguments were expected, and you’ll need to fix your code.

The Println function

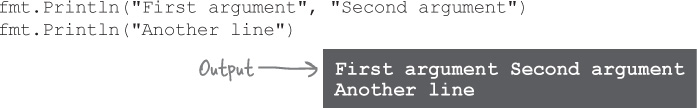

Use the Println function when you need to see what your program is doing. Any arguments you pass to it will be printed (displayed) in your terminal, with each argument separated by a space.

After printing all its arguments, Println will skip to a new terminal line. (That’s why “ln” is at the end of its name.)

Using functions from other packages

The code in our first program is all part of the main package, but the Println function is in the fmt package. (The fmt stands for “format.”) To be able to call Println, we first have to import the package containing it.

Once we’ve imported the package, we can access any functions it offers by typing the package name, a dot, and the name of the function we want.

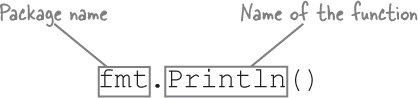

Here’s a code sample that calls functions from a couple other packages. Because we need to import multiple packages, we switch to an alternate format for the import statement that lets you list multiple packages within parentheses, one package name per line.

Once we’ve imported the math and strings packages, we can access the math package’s Floor function with math.Floor, and the strings package’s Title function with strings.Title.

You may have noticed that in spite of including those two function calls in our code, the above sample doesn’t display any output. We’ll look at how to fix that next.

Function return values

In our previous code sample, we tried calling the math.Floor and strings.Title functions, but they didn’t produce any output:

package main

import (

"math"

"strings"

)

func main() {

math.Floor(2.75)

strings.Title("head first go")

}

Note

This program produces no output!

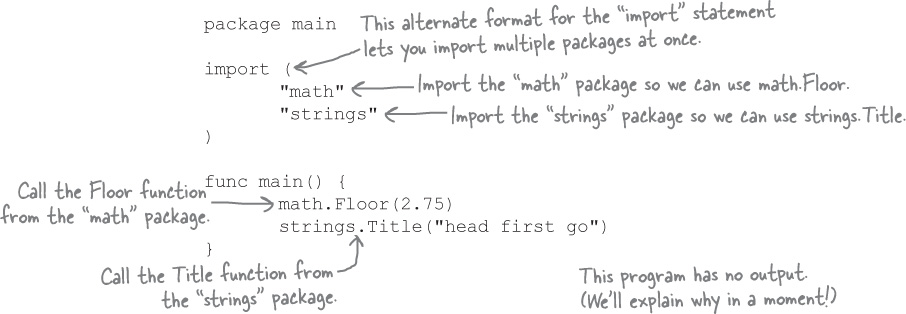

When we call the fmt.Println function, we don’t need to communicate with it any further after that. We pass one or more values for Println to print, and we trust that it printed them. But sometimes a program needs to be able to call a function and get data back from it. For this reason, functions in most programming languages can have return values: a value that the function computes and returns to its caller.

The math.Floor and strings.Title functions are both examples of functions that use return values. The math.Floor function takes a floating-point number, rounds it down to the nearest whole number, and returns that whole number. And the strings.Title function takes a string, capitalizes the first letter of each word it contains (converting it to “title case”), and returns the capitalized string.

To actually see the results of these function calls, we need to take their return values and pass those to fmt.Println:

Once this change is made, the return values get printed, and we can see the results.

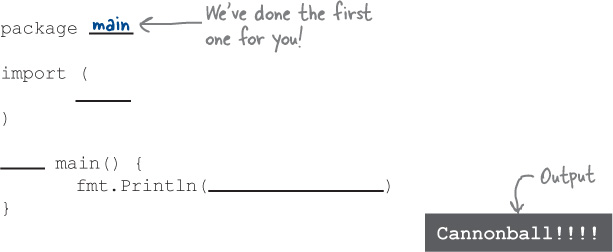

Pool Puzzle

Your job is to take code snippets from the pool and place them into the blank lines in the code. Don’t use the same snippet more than once, and you won’t need to use all the snippets. Your goal is to make code that will run and produce the output shown.

Note: each snippet from the pool can only be used once!

![]() Answers in “Pool Puzzle Solution”.

Answers in “Pool Puzzle Solution”.

Strings

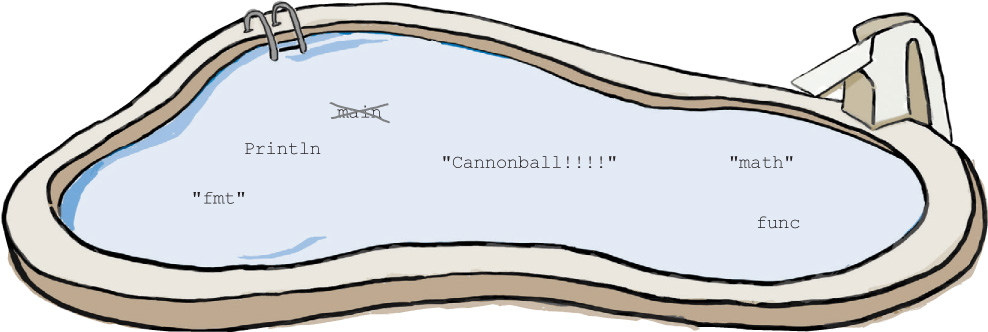

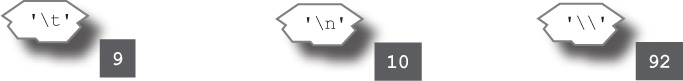

We’ve been passing strings as arguments to Println. A string is a series of bytes that usually represent text characters. You can define strings directly within your code using string literals: text between double quotation marks that Go will treat as a string.

Within strings, characters like newlines, tabs, and other characters that would be hard to include in program code can be represented with escape sequences: a backslash followed by characters that represent another character.

| Escape sequence | Value |

|---|---|

\n |

A newline character. |

\t |

A tab character. |

\" |

Double quotation marks. |

\\ |

A backslash. |

Runes

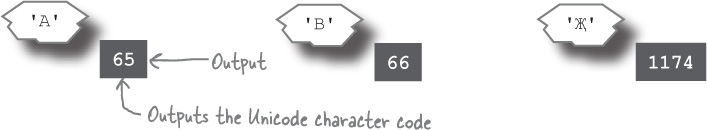

Whereas strings are usually used to represent a whole series of text characters, Go’s runes are used to represent single characters.

String literals are written surrounded by double quotation marks ("), but rune literals are written with single quotation marks (').

Go programs can use almost any character from almost any language on earth, because Go uses the Unicode standard for storing runes. Runes are kept as numeric codes, not the characters themselves, and if you pass a rune to fmt.Println, you’ll see that numeric code in the output, not the original character.

Just as with string literals, escape sequences can be used in a rune literal to represent characters that would be hard to include in program code:

Booleans

Boolean values can be one of only two values: true or false. They’re especially useful with conditional statements, which cause sections of code to run only if a condition is true or false. (We’ll look at conditionals in the next chapter.)

Numbers

You can also define numbers directly within your code, and it’s even simpler than string literals: just type the number.

As we’ll see shortly, Go treats integer and floating-point numbers as different types, so remember that a decimal point can be used to distinguish an integer from a floating-point number.

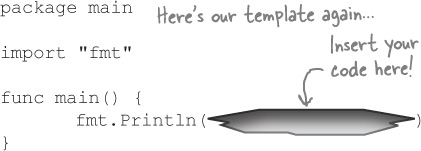

Math operations and comparisons

Go’s basic math operators work just like they do in most other languages. The + symbol is for addition, - for subtraction, * for multiplication, and / for division.

You can use < and > to compare two values and see if one is less than or greater than another. You can use == (that’s two equals signs) to see if two values are equal, and != (that’s an exclamation point and an equals sign, read aloud as “not equal”) to see if two values are not equal. <= tests whether the first value is less than or equal to the second, and >= tests whether the first value is greater than or equal to the second.

The result of a comparison is a Boolean value, either true or false.

Types

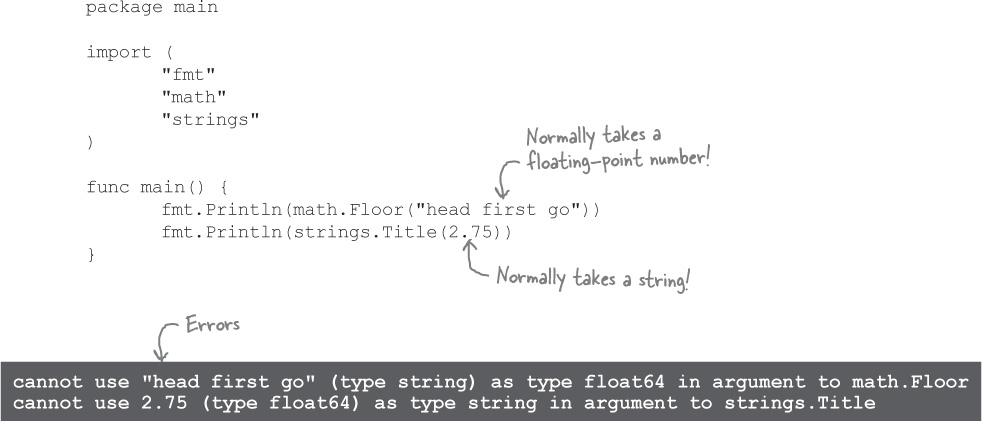

In a previous code sample, we saw the math.Floor function, which rounds a floating-point number down to the nearest whole number, and the strings.Title function, which converts a string to title case. It makes sense that you would pass a number as an argument to the Floor function, and a string as an argument to the Title function. But what would happen if you passed a string to Floor and a number to Title?

Go prints two error messages, one for each function call, and the program doesn’t even run!

Things in the world around you can often be classified into different types based on what they can be used for. You don’t eat a car or truck for breakfast (because they’re vehicles), and you don’t drive an omelet or bowl of cereal to work (because they’re breakfast foods).

Likewise, values in Go are all classified into different types, which specify what the values can be used for. Integers can be used in math operations, but strings can’t. Strings can be capitalized, but numbers can’t. And so on.

Go is statically typed, which means that it knows what the types of your values are even before your program runs. Functions expect their arguments to be of particular types, and their return values have types as well (which may or may not be the same as the argument types). If you accidentally use the wrong type of value in the wrong place, Go will give you an error message. This is a good thing: it lets you find out there’s a problem before your users do!

Go is statically typed. If you use the wrong type of value in the wrong place, Go will let you know.

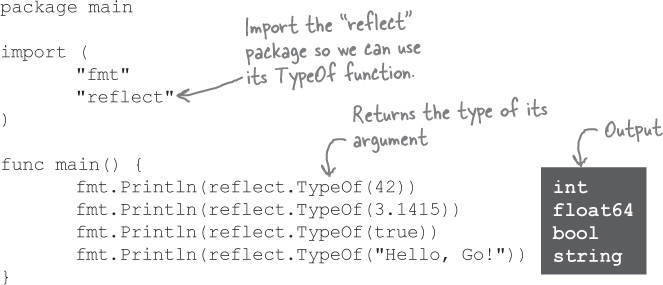

You can view the type of any value by passing it to the reflect package’s TypeOf function. Let’s find out what the types are for some of the values we’ve already seen:

Here’s what those types are used for:

| Type | Description |

|---|---|

int |

An integer. Holds whole numbers. |

float64 |

A floating-point number. Holds numbers with a fractional part. (The 64 in the type name is because 64 bits of data are used to hold the number. This means that float64 values can be fairly, but not infinitely, precise before being rounded off.) |

bool |

A Boolean value. Can only be true or false. |

string |

A string. A series of data that usually represents text characters. |

![]() Answers in “

Answers in “ Exercise Solutions”.

Exercise Solutions”.

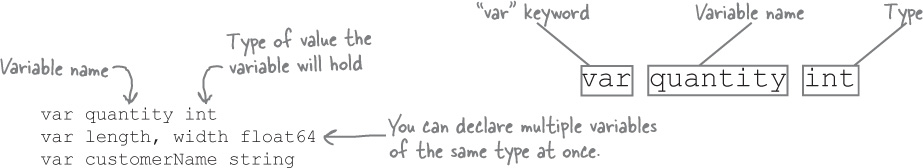

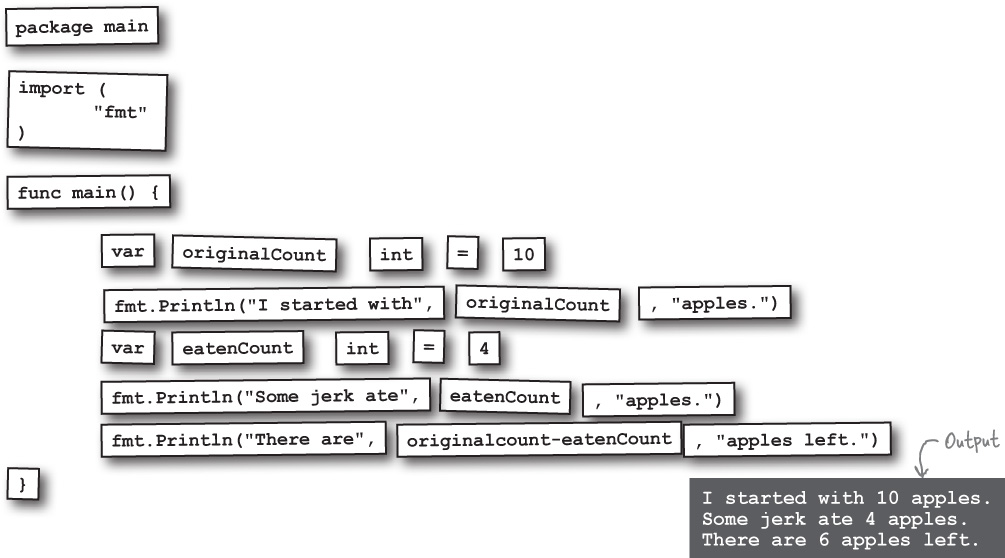

Declaring variables

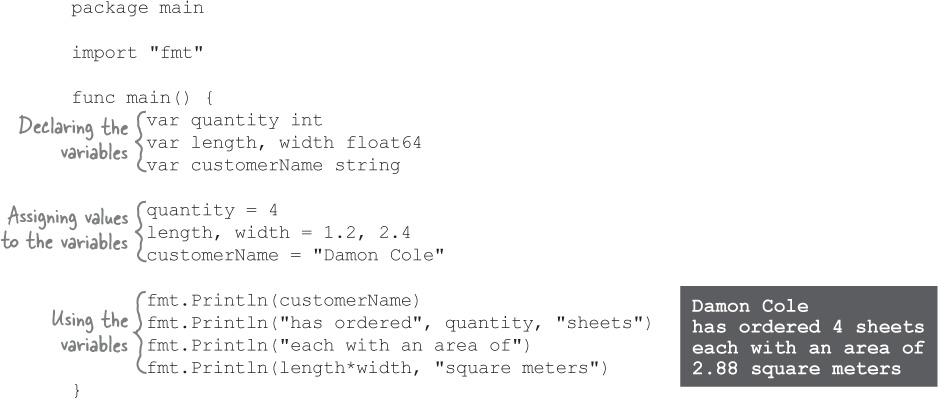

In Go, a variable is a piece of storage containing a value. You can give a variable a name by using a variable declaration. Just use the var keyword followed by the desired name and the type of values the variable will hold.

Once you declare a variable, you can assign any value of that type to it with = (that’s a single equals sign):

quantity = 2 customerName = "Damon Cole"

You can assign values to multiple variables in the same statement. Just place multiple variable names on the left side of the =, and the same number of values on the right side, separated with commas.

Once you’ve assigned values to variables, you can use them in any context where you would use the original values:

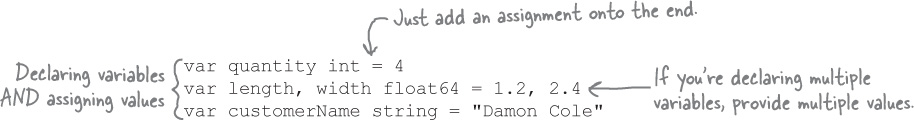

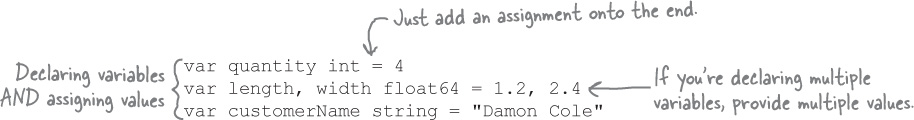

If you know beforehand what a variable’s value will be, you can declare variables and assign them values on the same line:

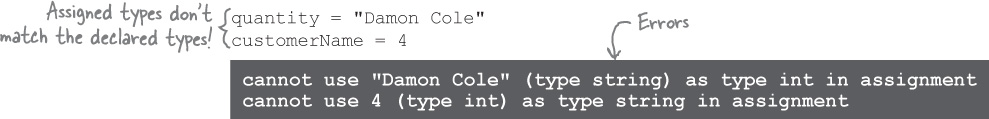

You can assign new values to existing variables, but they need to be values of the same type. Go’s static typing ensures you don’t accidentally assign the wrong kind of value to a variable.

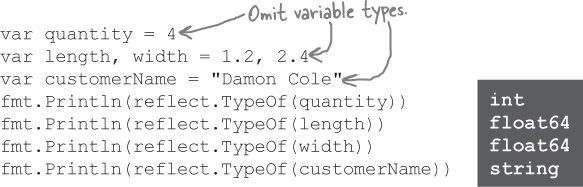

If you assign a value to a variable at the same time as you declare it, you can usually omit the variable type from the declaration. The type of the value assigned to the variable will be used as the type of that variable.

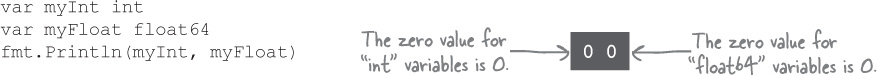

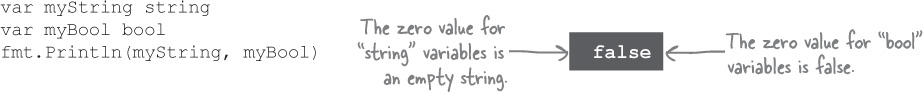

Zero values

If you declare a variable without assigning it a value, that variable will contain the zero value for its type. For numeric types, the zero value is actually 0:

But for other types, a value of 0 would be invalid, so the zero value for that type may be something else. The zero value for string variables is an empty string, for example, and the zero value for bool variables is false.

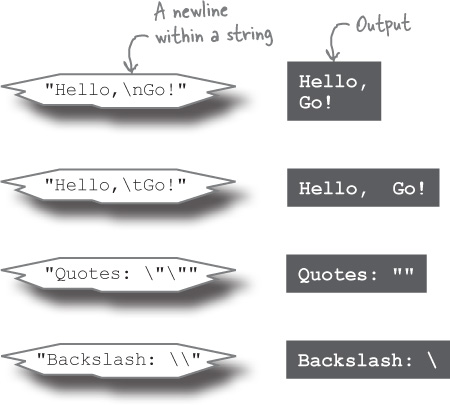

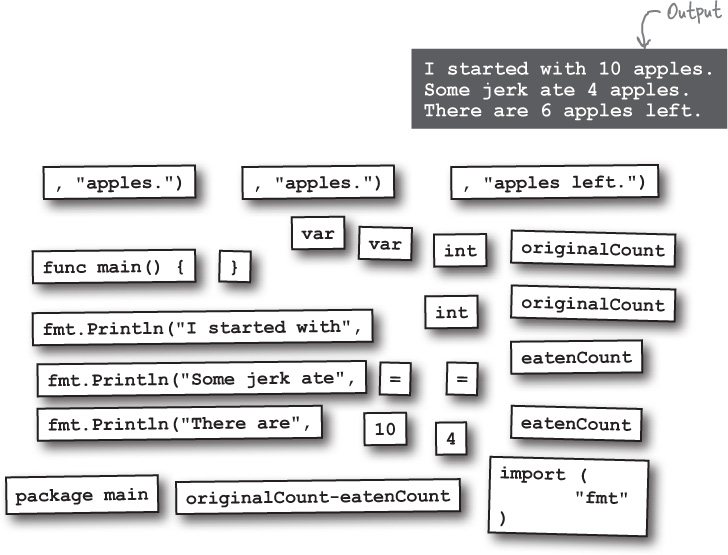

Code Magnets

A Go program is all scrambled up on the fridge. Can you reconstruct the code snippets to make a working program that will produce the given output?

![]() Answers in “Code Magnets Solution”.

Answers in “Code Magnets Solution”.

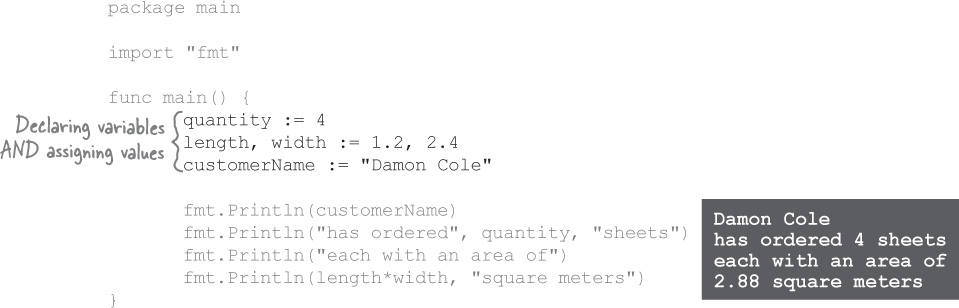

Short variable declarations

We mentioned that you can declare variables and assign them values on the same line:

But if you know what the initial value of a variable is going to be as soon as you declare it, it’s more typical to use a short variable declaration. Instead of explicitly declaring the type of the variable and later assigning to it with =, you do both at once using :=.

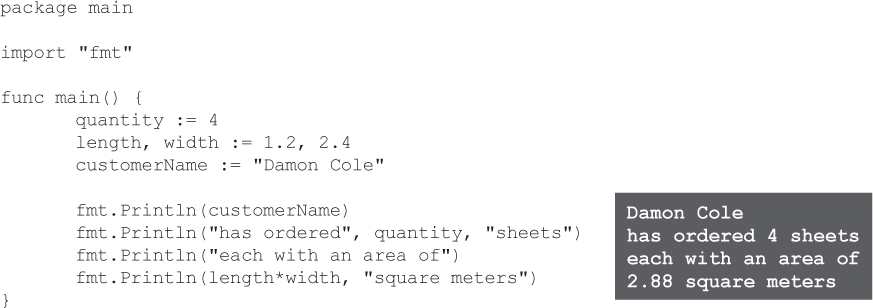

Let’s update the previous example to use short variable declarations:

There’s no need to explicitly declare the variable’s type; the type of the value assigned to the variable becomes the type of that variable.

Because short variable declarations are so convenient and concise, they’re used more often than regular declarations. You’ll still see both forms occasionally, though, so it’s important to be familiar with both.

Breaking Stuff is Educational!

Take our program that uses variables, try making one of the changes below, and run it. Then undo your change and try the next one. See what happens!

| If you do this... | ...it will fail because... |

|---|---|

Add a second declaration for the same variable quantity := 4 |

You can only declare a variable once. (Although you can assign new values to it as often as you want. You can also declare other variables with the same name, as long as they’re in a different scope. We’ll learn about scopes in the next chapter.) |

Delete the : from a short variable declaration quantity = 4 |

If you forget the :, it’s treated as an assignment, not a declaration, and you can’t assign to a variable that hasn’t been declared. |

Assign a string to an int variable quantity := 4 |

Variables can only be assigned values of the same type. |

Mismatch number of variables and values length, width := 1.2 |

You’re required to provide a value for every variable you’re assigning, and a variable for every value. |

Remove code that uses a variable fmt.Println(customerName) |

All declared variables must be used in your program. If you remove the code that uses a variable, you must also remove the declaration. |

Naming rules

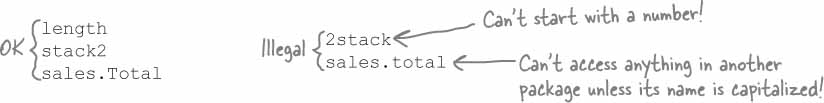

Go has one simple set of rules that apply to the names of variables, functions, and types:

A name must begin with a letter, and can have any number of additional letters and numbers.

If the name of a variable, function, or type begins with a capital letter, it is considered exported and can be accessed from packages outside the current one. (This is why the

Pinfmt.Printlnis capitalized: so it can be used from themainpackage or any other.) If a variable/function/type name begins with a lowercase letter, it is considered unexported and can only be accessed within the current package.

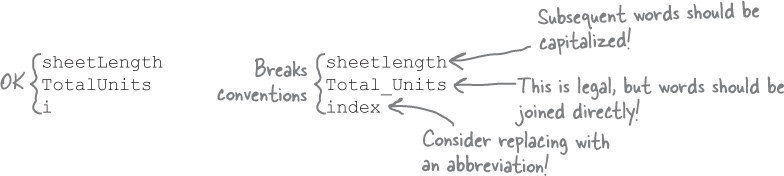

Those are the only rules enforced by the language. But the Go community follows some additional conventions as well:

If a name consists of multiple words, each word after the first should be capitalized, and they should be attached together without spaces between them, like this:

topPrice,RetryConnection, and so on. (The first letter of the name should only be capitalized if you want to export it from the package.) This style is often called camel case because the capitalized letters look like the humps on a camel.When the meaning of a name is obvious from the context, the Go community’s convention is to abbreviate it: to use

iinstead ofindex,maxinstead ofmaximum, and so on. (However, we at Head First believe that nothing is obvious when you’re learning a new language, so we will not be following that convention in this book.)

Only variables, functions, or types whose names begin with a capital letter are considered exported: accessible from packages outside the current package.

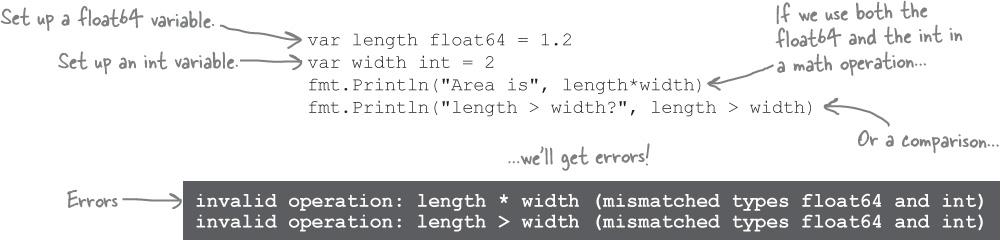

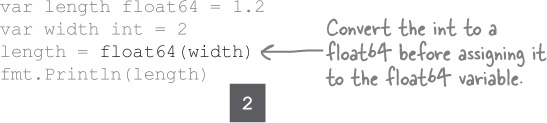

Conversions

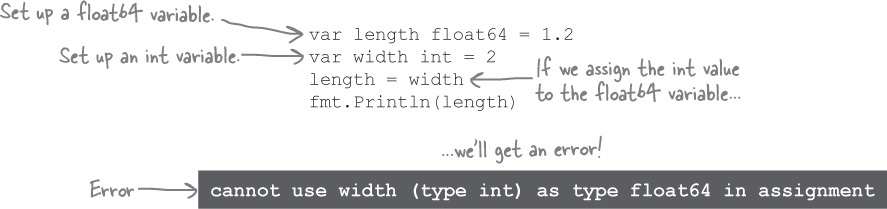

Math and comparison operations in Go require that the included values be of the same type. If they’re not, you’ll get an error when trying to run your code.

The same is true of assigning new values to variables. If the type of value being assigned doesn’t match the declared type of the variable, you’ll get an error.

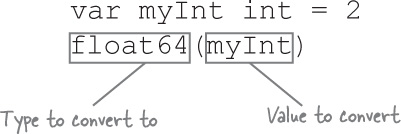

The solution is to use conversions, which let you convert a value from one type to another type. You just provide the type you want to convert a value to, immediately followed by the value you want to convert in parentheses.

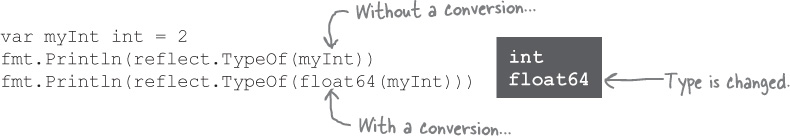

The result is a new value of the desired type. Here’s what we get when we call TypeOf on the value in an integer variable, and again on that same value after conversion to a float64:

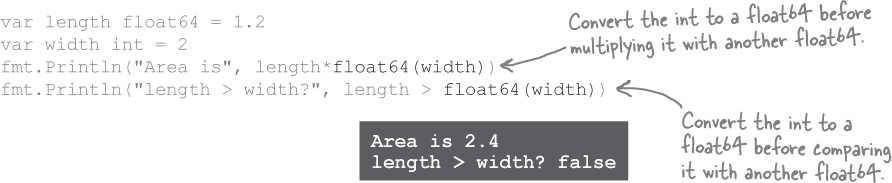

Let’s update our failing code example to convert the int value to a float64 before using it in any math operations or comparisons with other float64 values.

The math operation and comparison both work correctly now!

Now let’s try converting an int to a float64 before assigning it to a float64 variable:

Again, with the conversion in place, the assignment is successful.

When making conversions, be aware of how they might change the resulting values. For example, float64 variables can store fractional values, but int variables can’t. When you convert a float64 to an int, the fractional portion is simply dropped! This can throw off any operations you do with the resulting value.

As long as you’re cautious, though, you’ll find conversions essential to working with Go. They allow otherwise-incompatible types to work together.

Installing Go on your computer

The Go Playground is a great way to try out the language. But its practical uses are limited. You can’t use it to work with files, for example. And it doesn’t have a way to take user input from the terminal, which we’re going to need for an upcoming program.

So, to wrap up this chapter, let’s download and install Go on your computer. Don’t worry, the Go team has made it really easy! On most operating systems, you just have to run an installer program, and you’ll be done.

Visit https://golang.org in your web browser.

Click the download link.

Select the installation package for your operating system (OS). The download should begin automatically.

Visit the installation instructions page for your OS (you may be taken there automatically after the download starts), and follow the directions there.

Open a new terminal or command prompt window.

Confirm Go was installed by typing

go versionat the prompt and hitting the Return or Enter key. You should see a message with the version of Go that’s installed.

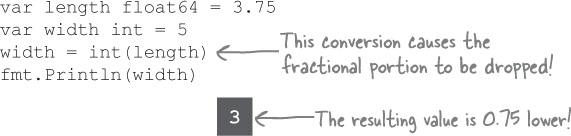

Compiling Go code

Our interaction with the Go Playground has consisted of typing in code and having it mysteriously run. Now that we’ve actually installed Go on your computer, it’s time to take a closer look at how this works.

Computers actually aren’t capable of running Go code directly. Before that can happen, we need to take the source code file and compile it: convert it to a binary format that a CPU can execute.

Let’s try using our new Go installation to compile and run our “Hello, Go!” example from earlier.

Using your favorite text editor, save our “Hello, Go!” code from earlier in a plain-text file named hello.go.

Open a new terminal or command prompt window.

In the terminal, change to the directory where you saved hello.go.

Run

go fmt hello.goto clean up the code formatting. (This step isn’t required, but it’s a good idea anyway.)Run

go build hello.goto compile the source code. This will add an executable file to the current directory. On macOS or Linux, the executable will be named just hello. On Windows, the executable will be named hello.exe.Run the executable file. On macOS or Linux, do this by typing

./hello(which means “run a program namedhelloin the current directory”). On Windows, just typehello.exe.

Go tools

When you install Go, it adds an executable named go to your command prompt. The go executable gives you access to various commands, including:

| Command | Description |

|---|---|

go build |

Compiles source code files into binary files. |

go run |

Compiles and runs a program, without saving an executable file. |

go fmt |

Reformats source files using Go standard formatting. |

go version |

Displays the current Go version. |

We just tried the go fmt command, which reformats your code in the standard Go format. It’s equivalent to the Format button on the Go Playground site. We recommend running go fmt on every source file you create.

Note

Most editors can be set up to automatically run go fmt every time you save a file! See https://blog.golang.org/go-fmt-your-code.

We also used the go build command to compile code into an executable file. Executable files like this can be distributed to users, and they’ll be able to run them even if they don’t have Go installed.

But we haven’t tried the go run command yet. Let’s do that now.

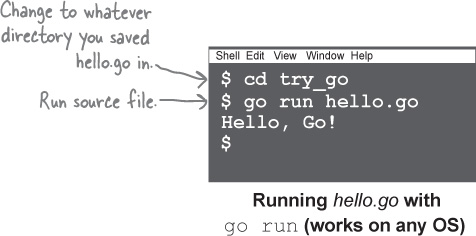

Try out code quickly with “go run”

The go run command compiles and runs a source file, without saving an executable file to the current directory. It’s great for quickly trying out simple programs. Let’s use it to run our hello.go sample.

Open a new terminal or command prompt window.

In the terminal, change to the directory where you saved hello.go.

Type

go run hello.goand hit Enter/Return. (The command is the same on all operating systems.)

You’ll immediately see the program output. If you make changes to the source code, you don’t have to do a separate compilation step; just run your code with go run and you’ll be able to see the results right away. When you’re working on small programs, go run is a handy tool to have!

Your Go Toolbox

That’s it for Chapter 1! You’ve added function calls and types to your toolbox.

Note

Function calls

A function is a chunk of code that you can call from other places in your program.

When calling a function, you can use arguments to provide the function with data.

Note

Types

Values in Go are classified into different types, which specify what the values can be used for.

Math operations and comparisons between different types are not allowed, but you can convert a value to a new type if needed.

Go variables can only store values of their declared type.

Pool Puzzle Solution

Code Magnets Solution

Get Head First Go now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.