How to Use This Book: Intro

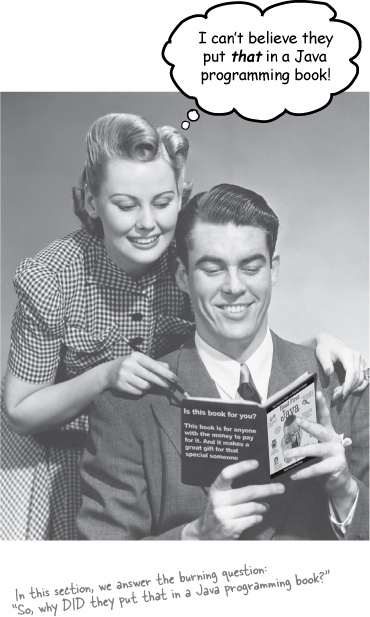

Who is this book for?

If you can answer “yes” to all of these:

Have you done some programming?

Do you want to learn Java?

Do you prefer stimulating dinner party conversation to dry, dull, technical lectures?

this book is for you.

Note

This is NOT a reference book. Head First Java is a book designed for learning, not an encyclopedia of Java facts.

Who should probably back away from this book?

If you can answer “yes” to any one of these:

Is your programming background limited to HTML only, with no scripting language experience?

(If you’ve done anything with looping, or if/then logic, you’ll do fine with this book, but HTML tagging alone might not be enough.)

Are you a kick-butt C++ programmer looking for a reference book?

Are you afraid to try something different? Would you rather have a root canal than mix stripes with plaid? Do you believe that a technical book can’t be serious if there’s a picture of a duck in the memory management section?

this book is not for you.

[note from marketing: who took out the part about how this book is for anyone with a valid credit card? And what about that “Give the Gift of Java” holiday promotion we discussed... -Fred]

We know what you’re thinking

“How can this be a serious Java programming book?”

“What’s with all the graphics?”

“Can I actually ...