How to use this Book: Intro

Who is this book for?

If you can answer “yes” to all of these:

Do you have access to a computer and some background in programming?

Do you want to learn techniques for building and delivering great software? Do you want to understand the principles behind iterations and test-driven development?

Do you prefer stimulating dinner party conversation to dry, dull, academic lectures?

this book is for you.

Who should probably back away from this book?

If you can answer “yes” to any of these:

Are you completely new to Java?

(You don’t need to be advanced, and if you know C++ or C# you’ll understand the code examples just fine.)

Are you a kick-butt development manager looking for a reference book?

Are you afraid to try something different? Would you rather have a root canal than mix stripes with plaid? Do you believe that a technical book can’t be serious if iterations are anthropomorphized?

this book is not for you.

We know what you’re thinking

“How can this be a serious software development book?”

“What’s with all the graphics?”

“Can I actually learn it this way?”

We know what your brain is thinking

Your brain craves novelty. It’s always searching, scanning, waiting for something unusual. It was built that way, and it helps you stay alive.

So what does your brain do with all the routine, ordinary, normal things you encounter? Everything it can to stop them from interfering with the brain’s real job—recording things that matter. It doesn’t bother saving the boring things; they never make it past the “this is obviously not important” filter.

How does your brain know what’s important? Suppose you’re out for a day hike and a tiger jumps in front of you, what happens inside your head and body?

Neurons fire. Emotions crank up. Chemicals surge.

And that’s how your brain knows...

This must be important! Don’t forget it!

But imagine you’re at home, or in a library. It’s a safe, warm, tiger-free zone. You’re studying. Getting ready for an exam. Or trying to learn some tough technical topic your boss thinks will take a week, ten days at the most.

Just one problem. Your brain’s trying to do you a big favor. It’s trying to make sure that this obviously non-important content doesn’t clutter up scarce resources. Resources that are better spent storing the really big things. Like tigers. Like the danger of fire. Like the guy with the handle “BigDaddy” on MySpace probably isn’t someone to meet with after 6 PM.

And there’s no simple way to tell your brain, “Hey brain, thank you very much, but no matter how dull this book is, and how little I’m registering on the emotional Richter scale right now, I really do want you to keep this stuff around.”

Metacognition: thinking about thinking

If you really want to learn, and you want to learn more quickly and more deeply, pay attention to how you pay attention. Think about how you think. Learn how you learn.

Most of us did not take courses on metacognition or learning theory when we were growing up. We were expected to learn, but rarely taught to learn.

But we assume that if you’re holding this book, you really want to learn how to really develop great software. And you probably don’t want to spend a lot of time. If you want to use what you read in this book, you need to remember what you read. And for that, you’ve got to understand it. To get the most from this book, or any book or learning experience, take responsibility for your brain. Your brain on this content.

The trick is to get your brain to see the new material you’re learning as Really Important. Crucial to your well-being. As important as a tiger. Otherwise, you’re in for a constant battle, with your brain doing its best to keep the new content from sticking.

So just how DO you get your brain to treat software development like it was a hungry tiger?

There’s the slow, tedious way, or the faster, more effective way. The slow way is about sheer repetition. You obviously know that you are able to learn and remember even the dullest of topics if you keep pounding the same thing into your brain. With enough repetition, your brain says, “This doesn’t feel important to him, but he keeps looking at the same thing over and over and over, so I suppose it must be.”

The faster way is to do anything that increases brain activity, especially different types of brain activity. The things on the previous page are a big part of the solution, and they’re all things that have been proven to help your brain work in your favor. For example, studies show that putting words within the pictures they describe (as opposed to somewhere else in the page, like a caption or in the body text) causes your brain to try to makes sense of how the words and picture relate, and this causes more neurons to fire. More neurons firing = more chances for your brain to get that this is something worth paying attention to, and possibly recording.

A conversational style helps because people tend to pay more attention when they perceive that they’re in a conversation, since they’re expected to follow along and hold up their end. The amazing thing is, your brain doesn’t necessarily care that the “conversation” is between you and a book! On the other hand, if the writing style is formal and dry, your brain perceives it the same way you experience being lectured to while sitting in a roomful of passive attendees. No need to stay awake.

But pictures and conversational style are just the beginning...

Here’s what WE did

We used pictures, because your brain is tuned for visuals, not text. As far as your brain’s concerned, a picture really is worth a thousand words. And when text and pictures work together, we embedded the text in the pictures because your brain works more effectively when the text is within the thing the text refers to, as opposed to in a caption or buried in the text somewhere.

We used redundancy, saying the same thing in different ways and with different media types, and multiple senses, to increase the chance that the content gets coded into more than one area of your brain.

We used concepts and pictures in unexpected ways because your brain is tuned for novelty, and we used pictures and ideas with at least some emotional content, because your brain is tuned to pay attention to the biochemistry of emotions. That which causes you to feel something is more likely to be remembered, even if that feeling is nothing more than a little humor, surprise, or interest.

We used a personalized, conversational style, because your brain is tuned to pay more attention when it believes you’re in a conversation than if it thinks you’re passively listening to a presentation. Your brain does this even when you’re reading.

We included more than 80 activities, because your brain is tuned to learn and remember more when you do things than when you read about things. And we made the exercises challenging-yet-do-able, because that’s what most people prefer.

We used multiple learning styles, because you might prefer step-by-step procedures, while someone else wants to understand the big picture first, and someone else just wants to see an example. But regardless of your own learning preference, everyone benefits from seeing the same content represented in multiple ways.

We include content for both sides of your brain, because the more of your brain you engage, the more likely you are to learn and remember, and the longer you can stay focused. Since working one side of the brain often means giving the other side a chance to rest, you can be more productive at learning for a longer period of time.

And we included stories and exercises that present more than one point of view, because your brain is tuned to learn more deeply when it’s forced to make evaluations and judgments.

We included challenges, with exercises, and by asking questions that don’t always have a straight answer, because your brain is tuned to learn and remember when it has to work at something. Think about it—you can’t get your body in shape just by watching people at the gym. But we did our best to make sure that when you’re working hard, it’s on the right things. That you’re not spending one extra dendrite processing a hard-to-understand example, or parsing difficult, jargon-laden, or overly terse text.

We used people. In stories, examples, pictures, etc., because, well, because you’re a person. And your brain pays more attention to people than it does to things.

Here’s what YOU can do to bend your brain into submission

So, we did our part. The rest is up to you. These tips are a starting point; listen to your brain and figure out what works for you and what doesn’t. Try new things.

Slow down. The more you understand, the less you have to memorize.

Don’t just read. Stop and think. When the book asks you a question, don’t just skip to the answer. Imagine that someone really is asking the question. The more deeply you force your brain to think, the better chance you have of learning and remembering.

Do the exercises. Write your own notes.

We put them in, but if we did them for you, that would be like having someone else do your workouts for you. And don’t just look at the exercises. Use a pencil. There’s plenty of evidence that physical activity while learning can increase the learning.

Read the “There are No Dumb Questions”

That means all of them. They’re not optional sidebars—they’re part of the core content! Don’t skip them.

Make this the last thing you read before bed. Or at least the last challenging thing.

Part of the learning (especially the transfer to long-term memory) happens after you put the book down. Your brain needs time on its own, to do more processing. If you put in something new during that processing time, some of what you just learned will be lost.

Drink water. Lots of it.

Your brain works best in a nice bath of fluid. Dehydration (which can happen before you ever feel thirsty) decreases cognitive function.

Talk about it. Out loud.

Speaking activates a different part of the brain. If you’re trying to understand something, or increase your chance of remembering it later, say it out loud. Better still, try to explain it out loud to someone else. You’ll learn more quickly, and you might uncover ideas you hadn’t known were there when you were reading about it.

Listen to your brain.

Pay attention to whether your brain is getting overloaded. If you find yourself starting to skim the surface or forget what you just read, it’s time for a break. Once you go past a certain point, you won’t learn faster by trying to shove more in, and you might even hurt the process.

Feel something.

Your brain needs to know that this matters. Get involved with the stories. Make up your own captions for the photos. Groaning over a bad joke is still better than feeling nothing at all.

Write a lot of software!

There’s only one way to learn to develop software: you have to actually develop software. And that’s what you’re going to do throughout this book. We’re going to give you lots of requirements to capture, techniques to evaluate, and code to test and improve: every chapter has exercises that pose a problem for you to solve. Don’t just skip over them—a lot of the learning happens when you solve the exercises. We included a solution to each exercise—don’t be afraid to peek at the solution if you get stuck! (It’s easy to get snagged on something small.) But try to solve the problem before you look at the solution.

Read Me

This is a learning experience, not a reference book. We deliberately stripped out everything that might get in the way of learning whatever it is we’re working on at that point in the book. And the first time through, you need to begin at the beginning, because the book makes assumptions about what you’ve already seen and learned.

We assume you are familiar with object-oriented programming.

It would take an entire book to teach you object-oriented programming (like, say, Head First OOA&D). We chose to focus this book on software development principles rather than design or language basics. We picked Java for our examples because it’s fairly common, and pretty self-documenting; but everything we talk about should apply whether you’re using Java, C#, C++, or Visual Basic (or Ruby, or...) However, if you’ve never programmed using an object-oriented language, you may have some trouble following some of the code. In that case we’d strongly recommend you get familiar with one of those languages before attacking some of the later chapters in the book.

We don’t cover every software development process out there.

There are tomes of information about different ways to write software. We don’t try to cover every possible approach to developing code. Instead, we focus on techniques that we know work and fit well together to produce great software. Chapter 12 specifically talks about ways to tweak your process to account for unique things on your project.

The activities are NOT optional.

The exercises and activities are not add-ons; they’re part of the core content of the book. Some of them are to help with memory, some are for understanding, and some will help you apply what you’ve learned. Some exercises are there just to make you think about how you would solve the problem. Don’t skip the exercises. The crossword puzzles are the only thing you don’t have to do, but they’re good for giving your brain a chance to think about the words and terms you’ve been learning in a different context.

The redundancy is intentional and important.

One distinct difference in a Head First book is that we want you to really get it. And we want you to finish the book remembering what you’ve learned. Most reference books don’t have retention and recall as a goal, but this book is about learning, so you’ll see some of the same concepts come up more than once.

The examples are as lean as possible.

Our readers tell us that it’s frustrating to wade through 200 lines of an example looking for the two lines they need to understand. Most examples in this book are shown within the smallest possible context, so that the part you’re trying to learn is clear and simple. Don’t expect all of the examples to be robust, or even complete—they are written specifically for learning, and aren’t always fully functional.

We’ve placed the full code for the projects on the Web so you can copy and paste them into your text editor. You’ll find them at:

http://www.headfirstlabs.com/books/hfsd/

The Brain Power exercises don’t have answers.

For some of them, there is no right answer, and for others, part of the learning experience of the Brain Power activities is for you to decide if and when your answers are right. In some of the Brain Power exercises, you will find hints to point you in the right direction.

The technical review team

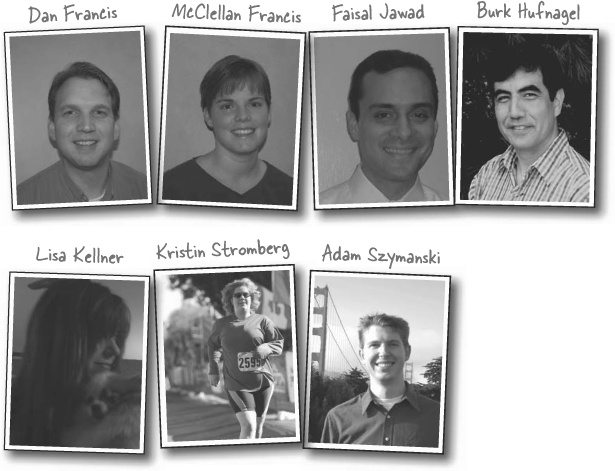

Technical Reviewers:

This book wouldn’t be anything like it is without our technical reviewers. They called us out when they disagreed with something, gave us “hurrah”s when something went right, and sent back lots of great commentary on things that worked and didn’t work for them in the real world. Each of them brought a different perspective to the book, and we really appreciate that. For instance, Dan Francis and McClellan Francis made sure this book didn’t turn into Software Development for Java.

We’d particularly like to call out Faisal Jawad for his thorough and supportive feedback (he started the “hurrahs”). Burk Hufnagel provided great suggestions on other approaches he’d used on projects and made one author’s late night of updates a lot more fun with his suggestion to include, “Bad dev team. No biscuit.”

Finally, we’d like to thank Lisa Kellner and Kristin Stromberg for their great work on readability and pacing. This book wouldn’t be what it is without all of your input.

Acknowledgments

Our editor:

Don’t let the picture fool you. Brett is one of the sharpest and most professional people we’ve ever worked with, and his contributions are on every page. Brett supported this book through every positive and negative review and spent quality time with us in Washington, D.C. to make this a success. More than once, he baited us into a good argument and then took notes while we went at it. This book is a result of his hard work and support and we really appreciate it.

The O’Reilly team:

Lou Barr is the reason these pages look so “awesome.” She’s responsible for turning our vaguely worded “something that conveys this idea and looks cool” comments into pages that teach the material like no other book around.

We’d also like to thank Laurie Petrycki for giving us the opportunity and making the tough decisions to get this book to where it is. We’d also like to thank Catherine Nolan and Mary Treseler for getting this book kicked off. Finally we’d like to thank Caitrin McCullough, Sanders Kleinfeld, Keith McNamara, and the rest of the O’Reilly production team for taking this book from the rough pages we sent in to a printed, high-class book with flawless grammar.

Scrum and XP from the Trenches:

We want to extend a special thanks to Henrik Kniberg for his book Scrum and XP from the Trenches. This book had significant influence on how we develop software and is the basis for some of the techniques we describe in this book. We’re very grateful for the excellent work he’s done.

Our families:

No acknowledgments page would be complete without recognizing the contributions and sacrifices our families made for this book. Vinny, Nick, and Tracey have picked up the slack in the Pilone house for almost two years while this book came together. I can’t convey how much I appreciate that and how your support and encouragement while “Daddy worked on his book” made this possible. Thank you.

A massive thank you also goes out to the Miles household, that’s Corinne (the boss) and Frizbee, Fudge, Snuff, Scrappy, and Stripe (those are the pigs). At every step you guys have kept me going and I really can’t tell you how much that means to me. Thanks!

Safari® Books Online

When you see a Safari® icon on the cover of your favorite technology book that means the book is available online through the O’Reilly Network Safari Bookshelf.

Safari offers a solution that’s better than e-books. It’s a virtual library that lets you easily search thousands of top tech books, cut and paste code samples, download chapters, and find quick answers when you need the most accurate, current information. Try it for free at http://safari.oreilly.com.

Get Head First Software Development now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.