Chapter 1. Introduction

This is a book about logs. Why would someone write so much about logs? It turns out that the humble log is an abstraction that is at the heart of a diverse set of systems, from NoSQL databases to cryptocurrencies. Yet other than perhaps occasionally tailing a log file, most engineers donât think much about logs. To help remedy that, Iâll give an overview of how logs work in distributed systems, and then give some practical applications of these concepts to a variety of common uses: data integration, enterprise architecture, real-time data processing, and data system design. Iâll also talk about my experiences putting some of these ideas into practice in my own work on data infrastructure systems at LinkedIn. But to start with, I should explain something you probably think you already know.

What Is a Log?

When most people think about logs they probably think about something that looks like Figure 1-1.

Every programmer is familiar with this kind of logâa series of loosely structured requests, errors, or other messages in a sequence of rotating text files.

This type of log is a degenerative form of the log concept I am going to describe. The biggest difference is that this type of application log is mostly meant for humans to read, whereas the logs Iâll be describing are also for programmatic access.

Actually, if you think about it, the idea of humans reading through logs on individual machines is something of an anachronism. This approach quickly becomes unmanageable when many services and servers are involved. The purpose of logs quickly becomes an input to queries and graphs in order to understand behavior across many machines, something that English text in files is not nearly as appropriate for as the kind of structured log Iâll be talking about.

Figure 1-1. An excerpt from an Apache log

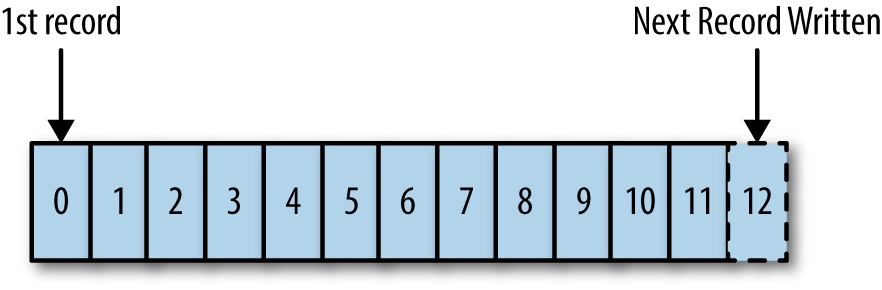

The log Iâll be discussing is a little more general and closer to what in the database or systems world might be called a commit log or journal. It is an append-only sequence of records ordered by time, as in Figure 1-2.

Figure 1-2. A structured log (records are numbered beginning with 0 based on the order in which they are written)

Each rectangle represents a record that was appended to the log. Records are stored in the order they were appended. Reads proceed from left to right. Each entry appended to the log is assigned a unique, sequential log entry number that acts as its unique key. The contents and format of the records arenât important for the purposes of this discussion. To be concrete, we can just imagine each record to be a JSON blob, but of course any data format will do.

The ordering of records defines a notion of âtimeâ since entries to the left are defined to be older then entries to the right. The log entry number can be thought of as the âtimestampâ of the entry. Describing this ordering as a notion of time seems a bit odd at first, but it has the convenient property of being decoupled from any particular physical clock. This property will turn out to be essential as we get to distributed systems.

A log is not all that different from a file or a table. A file is an array of bytes, a table is an array of records, and a log is really just a kind of table or file where the records are sorted by time.

You can see the analogy to the Apache log I showed earlier: both are append-only sequences of records. However, it is important that we think about the log as an abstract data structure, not a text file.

At this point you might be wondering, âWhy is it worth talking about something so simple?â How is an append-only sequence of records in any way related to data systems? The answer is that logs have a specific purpose: they record what happened and when. For distributed data systems this is, in many ways, the very heart of the problem.

Logs in Databases

I donât know where the log concept originatedâit is probably one of those things like binary search that is too simple for the inventor to realize it was an invention. It is present as early as IBMâs System R. The usage in databases has to do with keeping in sync a variety of data structures and indexes in the presence of crashes. To make this atomic and durable, a database uses a log to write out information about the records it will be modifying before applying the changes to all the various data structures that it maintains. The log is the record of what happened, and each table or index is a projection of this history into some useful data structure or index. Since the log is immediately persisted, it is used as the authoritative source in restoring all other persistent structures in the event of a crash.

Over time, the usage of the log grew from an implementation detail of the ACID database properties (atomicity, consistency, isolation, and durability) to a method for replicating data between databases. It turns out that the sequence of changes that happened on the database is exactly what is needed to keep a remote replica database in sync. Oracle, MySQL, PostgreSQL, and MongoDB include log shipping protocols to transmit portions of a log to replica databases that act as slaves. The slaves can then apply the changes recorded in the log to their own local data structures to stay in sync with the master. Oracle has productized the log as a general data subscription mechanism for non-Oracle data subscribers with their XStreams and GoldenGate products, and similar facilities exist in MySQL and PostgreSQL.

In fact, the use of logs in much of the rest of this book will be variations on the two uses in database internals:

- The log is used as a publish/subscribe mechanism to transmit data to other replicas

- The log is used as a consistency mechanism to order the updates that are applied to multiple replicas

Somehow, perhaps because of this origin in database internals, the concept of a machine readable log is not widely known, although, as we will see, this abstraction is ideal for supporting all kinds of messaging, data flow, and real-time data processing.

Logs in Distributed Systems

The same problems that databases solve with logs (like distributing data to replicas and agreeing on update order) are among the most fundamental problems for all distributed systems.

The log-centric approach to distributed systems arises from a simple observation that I will call the state machine replication principle:

If two identical, deterministic processes begin in the same state and get the same inputs in the same order, they will produce the same output and end in the same state.

This may seem a bit obtuse, so letâs dive in and understand what it means.

Deterministic means that the processing isnât timing dependent and doesnât let any other out-of-band input influence its results. For example, the following can be modeled as nondeterministic: a multithreaded program whose output depends on the order of execution of threads, or a program that makes decisions based on the results of a call to gettimeofday(), or some other non-repeatable source of input. Of course, whether these things are in fact truly deterministic is more a question about the foundations of physics. However, for our purposes it is fine that we donât know enough about their state and inputs to model their output as a proper mathematical function.

The state of the process is whatever data remains on the machine, either in memory or on disk, after our processing.

The part about getting the same input in the same order should ring a bellâthat is where the log comes in.

So this is actually a very intuitive notion: if you feed two deterministic pieces of code the same input log, they will produce the same output in the same order.

The application to distributed computing is pretty obvious. You can reduce the problem of making multiple machines all do the same thing to the problem of implementing a consistent log to feed input to these processes. The purpose of the log here is to squeeze all the nondeterminism out of the input stream to ensure that each replica that is processing this input stays in sync.

Once you understand it, there is nothing complicated or deep about this principle: it simply amounts to saying âdeterministic processing is deterministic.â Nevertheless, I think it is one of the more general tools for distributed systems design.

Nor is there anything new about this. If distributed computing is old enough to have a classical approach, this would be it.

However, the implications of this basic design pattern are not that widely appreciated, and the applications to enterprise architecture are appreciated even less.

One of the beautiful things about this is that the discrete log entry numbers now act as a clock for the state of the replicasâyou can describe the state of each replica by a single number: the timestamp for the maximum log entry that it has processed. Two replicas at the same time will be in the same state. Thus, this timestamp combined with the log uniquely capture the entire state of the replica. This gives a discrete, event-driven notion of time that, unlike the machineâs local clocks, is easily comparable between different machines.

Variety of Log-Centric Designs

There are many variations on how this principle can be applied, depending on what is put in the log. For example, we can log the incoming requests to a service and have each replica process these independently. Or we can have one instance process requests and log the state changes that the service undergoes in response to a request. Theoretically, we could even log a series of x86 machine instructions for each replica to execute, or the method name and arguments to invoke on each replica. As long as two processes handle these inputs in the same way, the processes will remain consistent across replicas.

Different communities describe similar patterns differently. Database people generally differentiate between physical and logical logging. Physical or row-based logging means logging the contents of each row that is changed. Logical or statement logging means not logging the changed rows, but instead logging the SQL commands that lead to the row changes (the insert, update, and delete statements).

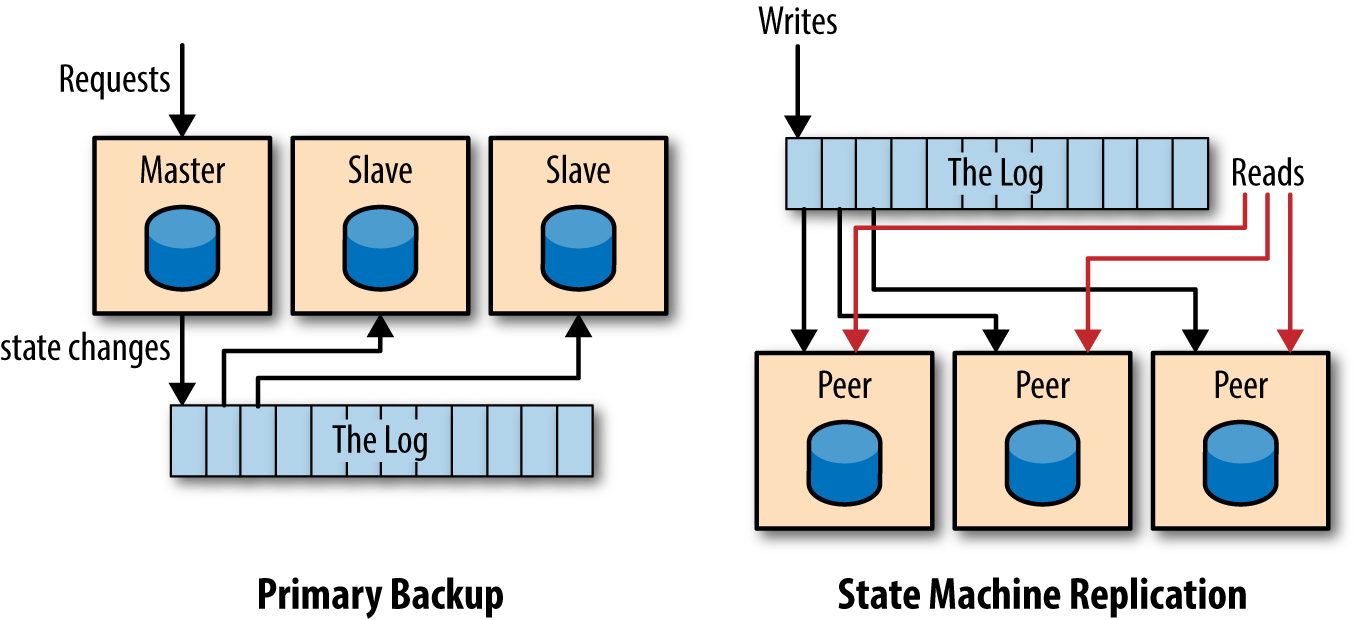

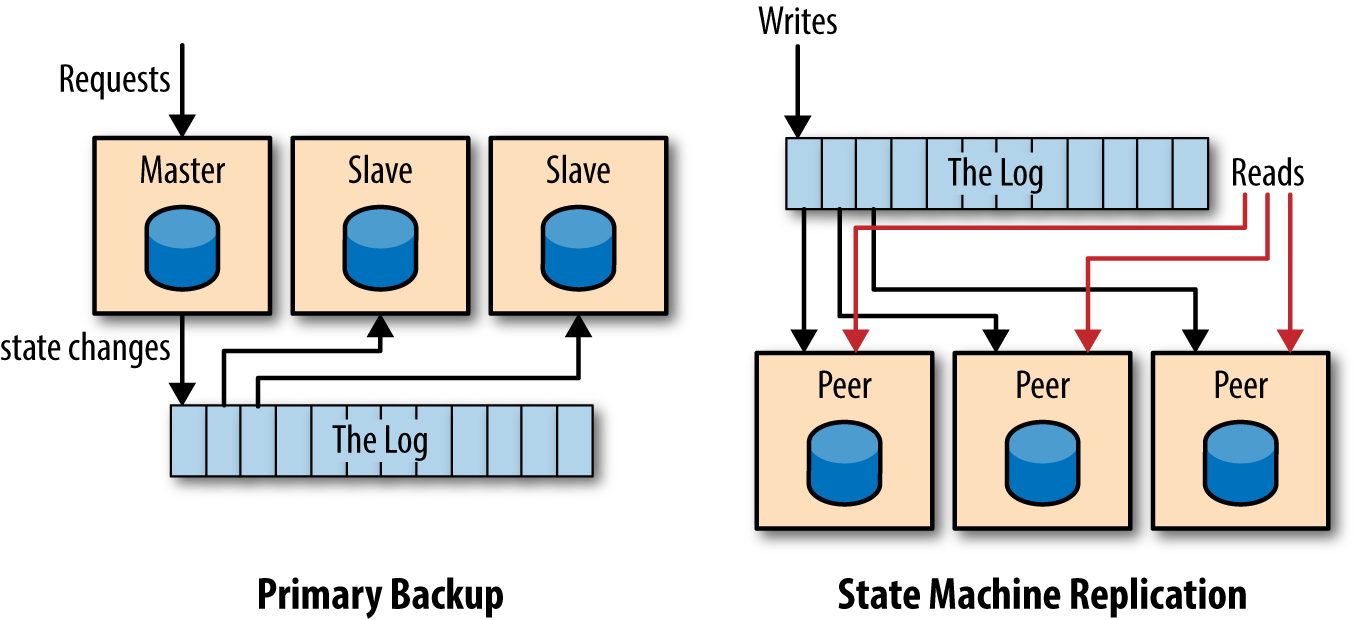

The distributed systems literature commonly distinguishes two broad approaches to processing and replication. The state machine model usually refers to an active-active model, where we keep a log of the incoming requests and each replica processes each request in log order. A slight modification of this, called the primary-backup model, is to elect one replica as the leader. This leader processes requests in the order they arrive and logs the changes to its state that occur as a result of processing the requests. The other replicas apply the state changes that the leader makes so that they will be in sync and ready to take over as leader, should the leader fail.

As shown in Figure 1-3, in the primary backup model a master node is chosen to handle all reads and writes. Each write is posted to the log. Slaves subscribe to the log and apply the changes that the master executed to their local state. If the master fails, a new master is chosen from the slaves. In the state machine replication model, all nodes are peers. Writes go first to the log and all nodes apply the write in the order determined by the log.

An Example

To understand different approaches to building a system using a log, letâs look at a toy problem. Say we want to implement a replicated arithmetic service that maintains a set of variables (initialized to zero) and applies additions, multiplications, subtractions, divisions, and queries on these values. Our service will respond to the following commands:

x? // get the current value of x x+=5 // add 5 to x x-=2 // subtract 2 from x y*=2 // double y

Letâs say that this is run as a remote web service, with requests and responses sent via HTTP.

If we have only a single server, the implementation will be quite simple. It can store the variables in memory or on disk and update them in whatever order it happens to receive requests. However, because there is only a single server, we lack fault tolerance and also have no way to scale out serving (should our arithmetic service become popular).

We can solve this by adding servers that replicate this state and processing logic. However this creates a new problem: the servers might get out of sync. There are many ways this could happen. For example, the servers could receive the update commands in different orders (not all operations are commutative), or a failed or nonresponsive server could miss updates.

Of course, in practice, most people would just push the queries and updates into a remote database. This moves the problem out of our application, but doesnât really solve it; after all, now we need to solve the fault tolerance problem in the database. So for the sake of the example, letâs directly discuss the use of a log in our application.

There are a few variations on solving this problem using a log. The state-machine replication approach would involve first writing to the log the operation that is to be performed, then having each replica apply the operations in the log order. In this case, the log would contain a sequence of commands like âx+=5â or ây*=2â.

A primary-backup approach is also possible. In this design, we would choose one of the replicas to act as the primary (or leader or master). This primary would locally execute whatever command it receives in the order requests arrive, and it would log out the series of variable values that result from executing the commands. In this design, the log contains only the resulting variable values, like âx=1â or ây=6â, not the original commands that created the values. The remaining replicas would act as backups (or followers or slaves);Â they subscribe to this log and passively apply the new variable values to their local stores. When the leader fails, we would choose a new leader from among the remaining replicas.

This example also makes it clear why ordering is key for ensuring consistency between replicas: reordering an addition and multiplication command will yield a different result, as will reordering two variable updates for the same variable.

Logs and Consensus

The distributed log can be seen as the data structure that models the problem of consensus. A log, after all, represents a series of decisions on the next value to append. You have to squint a little to see a log in the Paxos family of algorithms, although log building is their most common practical application. With Paxos, this is usually done using an extension of the protocol called âmulti-paxos,"Â which models the log as a series of consensus problems, one for each slot in the log. The log is much more prominent in other protocols such as ZAB, RAFT, and Viewstamped Replication, which directly model the problem of maintaining a distributed, consistent log.

My suspicion is that our view of this is a little biased by the path of history, perhaps due to the few decades in which the theory of distributed computing outpaced its practical application. In reality, the consensus problem is a bit too simple. Computer systems rarely need to decide a single value, they almost always handle a sequence of requests. So a log, rather than a simple single-value register, is the more natural abstraction.

Furthermore, the focus on the algorithms obscures the underlying log abstraction that systems need. I suspect we will end up focusing more on the log as a commoditized building block irrespective of its implementation in the same way that we often talk about a hash table without bothering to get into the details of whether we mean the murmur hash with linear probing or some other variant. The log will become something of a commoditized interface, with many algorithms and implementations competing to provide the best guarantees and optimal performance.

Changelog 101: Tables and Events Are Dual

Letâs come back to databases for a bit. There is a fascinating duality between a log of changes and a table. The log is similar to the list of all credits and debits a bank processes, while a table would be all the current account balances. If you have a log of changes, you can apply these changes in order to create the table and capture the current state. This table will record the latest state for each key (as of a particular log time). There is a sense in which the log is the more fundamental data structure: in addition to creating the original table, you can also transform it to create all kinds of derived tables. (And yes, table can mean keyed data store for you non-relational folks.)

This process works in reverse as well: if you have a table taking updates, you can record these changes and publish a changelog of all the updates to the state of the table. This changelog is exactly what you need to support near-real-time replicas. In this sense, you can see tables and events as dual: tables support data at rest and logs capture change. The magic of the log is that if it is a complete log of changes, it holds not only the contents of the final version of the table, but can also recreate all other versions that might have existed. It is, effectively, a sort of backup of every previous state of the table.

This might remind you of source code version control. There is a close relationship between source control and databases. Version control solves a very similar problem to what distributed data systems have to solve: managing distributed, concurrent changes in state. A version control system usually models the sequence of patches, which is in effect a log. You interact directly with a checked-out snapshot of the current code, which is analogous to the table. Note that in version control systems, as in other distributed stateful systems, replication happens via the log: when you update, you just pull down the patches and apply them to your current snapshot.

Some people have seen some of these ideas recently from Datomic, a company selling a log-centric database. These concepts are not unique to this system, of course, as they have been a part of the distributed systems and database literature for well over a decade.

This may all seem a little theoretical. Do not despair! Weâll get to the practical stuff quickly.

Whatâs Next

In the remainder of this book, I will give you a flavor of what a log is good for that goes beyond the internals of distributed systems or abstract distributed computing models, including:

- Data integration

- Making all of an organizationâs data easily available in all its storage and processing systems.

- Real-time data processing

- Computing derived data streams.

- Distributed system design

- How practical systems can by simplified with a log-centric design.

These uses all revolve around the idea of a log as a standalone service.

In each case, the usefulness of the log comes from the simple function that the log provides: producing a persistent, replayable record of history. Surprisingly, at the core of the previously mentioned log uses is the ability to have many machines play back history at their own rates in a deterministic manner.

Get I Heart Logs now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.