Chapter 4. Building Data Systems with Logs

The final topic I want to discuss is the role of the log in the internals of online data systems.

There is an analogy here between the role a log serves for data flow inside a distributed database and the role it serves for data integration in a larger organization. In both cases, it is responsible for data flow, consistency, and recovery. What, after all, is an organization if not a very complicated distributed data system?

Maybe if you squint a bit, you can see the whole of your organizationâs systems and data flows as a single very complicated distributed database. You can view all the individual query-oriented systems (Redis, SOLR, Hive tables, and so on) as just particular indexes on your data. You can view a stream processing system like Storm or Samza as just a very well-developed trigger-and-view materialization mechanism. Classical database people, I have noticed, like this view very much because it finally explains to them what on earth people are doing with all these different data systemsâthey are just different index types!

There is now undeniably an explosion of types of data systems, but in reality, this complexity has always existed. Even in the heyday of the relational database, organizations had many relational databases! So perhaps real integration hasnât existed since the mainframe when all the data really was in one place. There are many motivations for segregating data into multiple systems: scale, geography, security, and performance isolation are the most common. These issues can be addressed by a good system; for example, it is possible for an organization to have a single Hadoop cluster that contains all the data and serves a large and diverse constituency.

So there is already one possible simplification in the handling of data in the move to distributed systems: coalescing many little instances of each system into a few big clusters. Many systems arenât good enough to allow this yet because they donât have security, canât guarantee performance isolation, or just donât scale well enough. However, each of these problems is solvable. Instead of running many little single server instances of a system, you can instead run one big multitenant system shared by all the applications of an entire organization. This allows for huge efficiencies in management and utilization.

Unbundling?

My take is that the explosion of different systems is caused by the difficulty of building distributed data systems. By cutting back to a single query type or use case, each system is able to bring its scope down into the set of things that are feasible to build. Running all of these systems yields too much complexity.

I see three possible directions this could follow in the future.

The first possibility is a continuation of the status quo: the separation of systems remains more or less as it is for a good deal longer. This could happen either because the difficulty of distribution is too hard to overcome or because this specialization allows new levels of convenience and power for each system. As long as this remains true, the data integration problem will remain one of the most centrally important issues for the successful use of data. In this case, an external log that integrates data will be very important.

The second possibility is that there could be a reconsolidation in which a single system with enough generality starts to merge all the different functions back into a single uber-system. This uber-system could be superficially like the relational database, but its use in an organization would be far different, as you would need only one big system instead of umpteen little ones. In this world, there is no real data integration problem except what is solved inside this system. I think the practical difficulties of building such a system make this unlikely.

There is another possible outcome, though, which I actually find appealing as an engineer. One interesting facet of the new generation of data systems is that they are virtually all open source. Open source allows another possibility: data infrastructure could be unbundled into a collection of services and application-facing system API. You already see this happening to a certain extent in the Java stack:

- Zookeeper handles much of the system coordination (perhaps with a bit of help from higher-level abstractions like Helix or Curator).

- Mesos and YARN process virtualization and resource management.

- Embedded libraries like Lucene, RocksDB, and LMDB do indexing.

- Netty, Jetty, and higher-level wrappers like Finagle and rest.li handle remote communication.

- Avro, Protocol Buffers, Thrift, and umpteen zillion other libraries handle serialization.

- Kafka and BookKeeper provide a backing log.

If you stack these things in a pile and squint a bit, it starts to look like a LEGO version of distributed data system engineering. You can piece these ingredients together to create a vast array of possible systems. This is clearly not a story relevant to end users who presumably care more about the API than about how it is implemented, but it might be a path towards getting the simplicity of the single system in a more diverse and modular world that continues to evolve. If the implementation time for a distributed system goes from years to weeks because reliable, flexible building blocks emerge, then the pressure to coalesce into a single monolithic system disappears.

The Place of the Log in System Architecture

A system that assumes that an external log is present allows the individual systems to relinquish much of their own complexity and rely on the shared log. Here are some things a log can do:

- Handle data consistency (whether eventual or immediate) by sequencing concurrent updates to nodes

- Provide data replication between nodes

- Provide âcommitâ semantics to the writer (such as acknowledging only when your write is guaranteed not to be lost)

- Provide the external data subscription feed from the system

- Provide the capability to restore failed replicas that lost their data or bootstrap new replicas

- Handle rebalancing of data between nodes

This is actually a substantial portion of what a distributed data system does. In fact, the majority of what is left over is related to the final client-facing query API and indexing strategy. This is exactly the part that should vary from system to system; for example, a full-text search query might need to query all partitions, whereas a query by primary key might only need to query a single node responsible for that keyâs data.

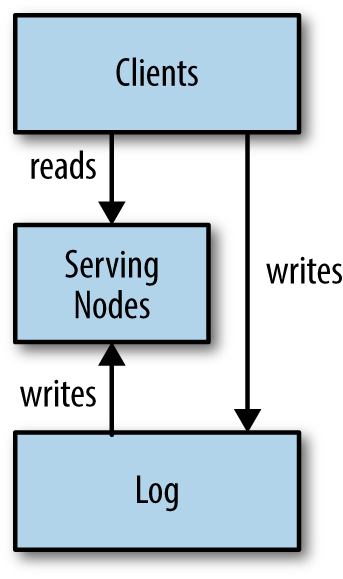

Here is how this works. The system is divided into two logical pieces: the log and the serving layer. The log captures the state changes in sequential order. The serving nodes store whatever index is required to serve queries (for example, a key-value store might have something like a btree or sstable, while a search system would have an inverted index). Writes can either go directly to the log, although they might be proxied by the serving layer. Writing to the log yields a logical timestamp (say the index in the log). If the system is partitioned, and I assume it is, then the log and the serving nodes will have the same number of partitions, even though they may have very different numbers of machines.

The serving nodes subscribe to the log and apply writes as quickly as possible to their local indexes in the order that the log has stored them (see Figure 4-1).

Figure 4-1. A simplified architecture for a log-centric data system

The client can get read-your-write semantics from any node by providing the timestamp of a write as part of its query. A serving node receiving such a query will compare the desired timestamp to its own index point, and if necessary, delay the request until it has indexed up to at least that time to avoid serving stale data.

The serving nodes may or may not need to have any notion of mastership or leader election. For many simple use cases, the serving nodes can be completely without leaders, since the log is the source of truth.

One of the trickier things a distributed system must do is handle restoring failed nodes or moving partitions from node to node. A typical approach would have the log retain only a fixed window of data and combine this with a snapshot of the data stored in the partition. It is equally possible for the log to retain a complete copy of data and compact the log itself. This moves a significant amount of complexity out of the serving layer, which is system-specific, and into the log, which can be general purpose.

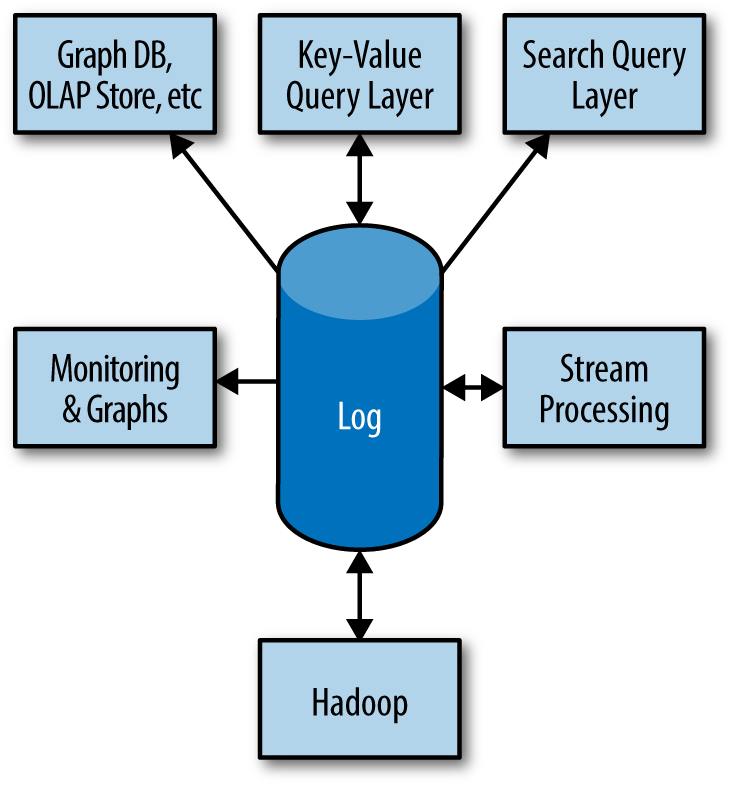

By having this log system, you get a fully developed subscription API for the contents of the data store that feeds ETL into other systems. In fact, many systems can share the same log while providing different indexes, as shown in Figure 4-2:

Figure 4-2. A log-centric infrastructure stack

Note how such a log-centric system is itself immediately a provider of data streams for processing and loading in other systems. Likewise, a stream processor can consume multiple input streams and then serve them via another system that indexes that output.

I find this view of systems as factored into a log and query API to be very revealing, as it lets you separate the query characteristics from the availability and consistency aspects of the system. I actually think this is even a useful way to mentally factor a system that isnât built this way to better understand it.

Itâs worth noting that although Kafka and BookKeeper are consistent logs, this is not a requirement. You could just as easily factor a Dynamo-like database into an eventually consistent AP log and a key-value serving layer. Such a log is a bit tricky to work with, as it will redeliver old messages and depends on the subscriber to handle this (much like Dynamo itself).

The idea of having a separate copy of data in the log (especially if it is a complete copy) strikes many people as wasteful. In reality, there are a few factors that make this less of an issue. First, the log can be a particularly efficient storage mechanism. We have the better part of a petabyte (PB) of log storage in Kafka in our live data-centers. Meanwhile, many serving systems require much more memory to serve data efficiently (text search, for example, is often all in memory). The serving system might also use optimized hardware. For example, most of our live data systems either serve out of memory or use SSDs. In contrast, the log system does only linear reads and writes, so it is quite happy using large multiterabyte hard drives. Finally, as shown in Figure 4-2, in the case where the data is served by multiple systems, the cost of the log is amortized over multiple indexes. This combination makes the expense of an external log fairly minimal.

This is exactly the pattern that LinkedIn has used to build out many of its own real-time query systems. These systems take as input either the log directly generated by database updates or else a log derived from other real-time processing, and provide a particular partitioning, indexing, and query capability on top of that data stream. This is how we have implemented our search, social graph, newsfeed, and OLAP query systems. In fact, it is quite common to have a single data feed (whether a live feed or a derived feed coming from Hadoop) replicated into multiple serving systems for live serving. This log-oriented data flow has proven to be an enormous simplifying assumption. None of these systems need to have an externally accessible write API at all; Kafka and databases are used as the system of record, and changes flow to the appropriate query systems through that log. Writes are handled locally by the nodes hosting a particular partition. These nodes blindly transcribe the feed provided by the log to their own store. A failed node can be restored by replaying the upstream log.

The degree to which these systems rely on the log varies. A fully reliant system could make use of the log for data partitioning, node restore, rebalancing, and all aspects of consistency and data propagation. In this setup, the actual serving tier is nothing less than a sort of cache structured to enable a particular type of processing, with writes going directly to the log.

Conclusion

Logs give us a principled way to model changing data as it cascades through a distributed system. This works just as well to model data flow in a large enterprise as it does for the internals of data flow in a distributed database. Having this kind of basic abstraction in place gives us a way of gluing together disparate data systems, processing real-time changes, as well as a being an interesting system and application architecture in its own right. In some sense, all of our systems are distributed systems now, so what was once a somewhat esoteric implementation detail of a distributed database is now a concept that is quite relevant to the modern software engineer.

Get I Heart Logs now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.