Chapter 1. Introduction

MacOS High Sierra is the 13th major version of Apple’s Unix-based operating system. It’s got very little in common with the original Mac operating system, the one that saw Apple through the 1980s and 1990s. Apple dumped that in 2001, when CEO Steve Jobs decided it was time for a change. Apple had spent too many years piling new features onto a software foundation originally poured in 1984. Programmers and customers complained of the “spaghetti code” the Mac OS had become.

So today, underneath macOS’s classy, translucent desktop is Unix, the industrial-strength, rock-solid OS that drives many a website and university. It’s not new by any means; in fact, it’s decades old and has been polished by generations of programmers.

Note

Beginning with Sierra in 2016, Apple stopped calling the Mac operating system “OS X.” It’s now “macOS.” That’s partly because Apple sought consistency with the software in its other products—iOS and watchOS—and partly, no doubt, because it was tired of hearing people pronounce it “oh ess sex.”

What’s New in High Sierra

Having run out of big cat species (Lion, Jaguar, Panther, Tiger, Leopard, Snow Leopard), Apple has begun naming its Mac operating systems after rock formations in California. There was Yosemite, and then El Capitan, and then Sierra, after the Sierra Nevada mountain range. As its name suggests, High Sierra is really just a refinement of last year’s Sierra.

High Sierra doesn’t look any different from El Capitan, Yosemite, or Sierra before it. Instead, it’s a representation of all the little nips and tucks that Apple engineers wished they’d had time to put into the last version.

A New File System

The file system is the underlying, invisible software that controls the management of files and folders on your Mac. For almost 20 years, Mac fans used one called HFS+. And now there’s the Apple File System, or APFS, designed for the new era of solid-state drives, like the one in Mac laptops.

Most of its benefits are under the hood: far better security (for example, more-sophisticated FileVault encryption for your whole hard drive), better crash resistance, more efficient storage, and faster operation.

These are the two aspects of APFS you’ll probably notice first:

You know the column that shows you how big the files and folders in a window are? Now those numbers don’t need time to appear. They’re instantly there.

You can now duplicate a file or a folder instantly, no matter how big it is.

Safari Upgrades

Apple has continued to work on Safari, its web browser—and says that the new version is the fastest desktop browser in the world.

It also uses less power. Apple claims you can watch Netflix for two hours longer in Safari than other browsers.

Maybe even more thrilling to the world’s Internet surfers (and less thrilling to advertisers), Safari can now auto-block auto-play videos. For each website, you can choose Safari→Settings for This Website and specify that videos are never allowed to play; always allowed to play; or allowed only if they don’t have sound.

This feature works beautifully, and it makes the Internet a calmer place.

That’s not the only way Safari will frustrate advertisers. Apple says that “Safari now uses machine learning to identify advertisers and others who track your online behavior, and removes the cross-site tracking data they leave behind.”

This is cool, too: You can create different viewing settings for different sites. You might like The New York Times site to appear with larger text, Flash turned on for Dilbert.com, and so on. Page zoom, Reader view, location services, and use of your camera and microphone are among the settings memorized for each site.

And if you like the Reader view—which hides all ads, navigation stuff, blinking stuff, competing colors and fonts—you can now tell Safari to use it for everything. Every time you open an article that works with Reader, it pops into that format automatically. You end up with far fewer migraines from just trying to surf the web.

Photos

Ladies and gentlemen, the Photos app is finally ready for prime time.

The editing tools have been redesigned and goosed nearly to Photoshop levels; you can now manipulate the curves of a photo’s histogram, or edit only the reds (for example) in a photo.

The Auto-Fix button is now right on the Photos main toolbar; you can now send a photo into an external program (like Photoshop) for more powerful editing; a new Imports view shows not just the latest batch of imported photos, but the batch before that, and the batch before that, and so on; Memories (automatically grouped and curated slideshows with music) are much smarter now, capable of auto-building slideshows of your pets, babies, outdoor activities, performances, weddings, birthdays, and games; and Apple has opened up its “order your photos printed on mousepads, books, and calendars” feature to other companies. Soon, you’ll be able to install Photos extensions that permit all kinds of photo-product ordering.

Finally, Apple introduces some editing options to Live Photos: weird, three-second video clips that the iPhone can capture. You can now shorten a Live Photo, mute its audio, or extract a single frame to use as a still photo. Photos can also suggest a “boomerang” effect (bounces back and forth) or a loop (repeats over and over). And it has a new Slow Shutter filter, which (for example) blurs a babbling brook or stars moving across the sky, as though taken with a long exposure.

Notes

The Notes app has continued to improve, too.

Pin your best Notes. You can now pin your most-used notes (to-do lists, grocery lists, and so on) to the top of the list, so they don’t get sorted down chronologically as they do now. They’ll show up on your iPhone or iPad similarly pinned.

Tables. Yes! You can add a table to a Note. Great for bake-sale assignments, sports scores, and so on.

Miscellaneous

There are lots of smaller changes. For example:

Smaller multimedia. In both iOS 11 and High Sierra, Apple offers new file formats that permit your photos and videos to look the same as before but to consume only half the space. This is a huge deal for anyone whose phone or Mac is constantly filled up. For photos, it’s called the High Efficiency Image File Format (HEIF); for videos, it’s the High Efficiency Video Codec (HEVC, or H.265). When you export these photos and videos to a non-Apple machine, they convert to standard formats like JPEG and H.264.

Mail enhancements. When you search in Mail, a Top Hits section presents the messages Mail thinks are the best matches (based on Read status, senders you’ve replied to, your VIPs, and so on). Mail also offers a split-screen view when composing new messages in full-screen mode. And it stores your messages in 35 percent less disk space. More space is always welcome.

A new voice for Siri. The new male and female voices sound much more like actual people. (They’re the same ones that appeared in the recent iOS 11 release.)

iCloud file sharing. Finally, you can share files you’ve stored on your iCloud Drive with other people, just as you’ve been able to do through Dropbox for years. To do so, right-click or two-finger click an icon; from the shortcut menu, choose Add People. Now you can send an invitation to anyone by message, email, or whatever, and you can specify how much editing control they have. The catch, of course, is that the recipient must be using iOS 11 (on an iPhone or iPad) or High Sierra (on a Mac).

Capture a FaceTime moment as a Live Photo. You can snap a three-second snippet of a video chat—a Live Photo—for later sharing. (The other person gets notified, and can block you.)

Messages in iCloud. When you sign into any new Mac, iPhone, or iPad with your iCloud credentials, your entire texting history gets downloaded automatically. (As it is now, you can’t see the Message transcript history with someone on a new machine.) Saving the Messages history online also saves disk space on your Mac.

Family storage sharing. You can now share an iCloud storage plan with family members.

More Spotlight wisdom. The Spotlight search feature can now provide flight arrival and departure times, terminals, gates, delays, and flight maps when you type in a flight number. It can also return multiple Wikipedia results on a single screen.

Developer goodies. Apple now offers development kits for virtual reality and augmented reality, hoping to jump-start new apps in an area where Apple is now way behind. There’s a new version of Metal, too, the Mac software that addresses your graphics card.

So the changes in High Sierra are, as you’re figuring out, pretty subtle. This new OS won’t throw anyone for a loop. But it’s a big speed-up with a lot of touch-ups—for free.

About This Book

To find your way around macOS High Sierra, you’re expected to use Apple’s online help system. And as you’ll quickly discover, these help pages are tersely written, offer very little technical depth, lack useful examples, and provide no tutorials whatsoever. You can’t mark your place, underline, or read them in the bathroom.

The purpose of this book, then, is to serve as the manual that should have accompanied macOS—version 10.13 in particular.

MacOS High Sierra: The Missing Manual is designed to accommodate readers at every technical level. The primary discussions are written for advanced-beginner or intermediate Mac fans. But if you’re a Mac first-timer, miniature sidebar articles called Up to Speed provide the introductory information you need to understand the topic at hand. If you’re a Mac veteran, on the other hand, keep your eye out for similar shaded boxes called Power Users’ Clinic. They offer more-technical tips, tricks, and shortcuts.

When you write a book like this, you do a lot of soul-searching about how much to cover. Of course, a thinner book, or at least a thinner-looking one, is always preferable; plenty of readers are intimidated by a book that dwarfs the Tokyo White Pages.

On the other hand, Apple keeps adding features and rarely takes them away. So this book isn’t getting any skinnier.

Even so, some chapters come with free downloadable appendixes—PDF documents, available on this book’s “Missing CD” page at www.missingmanuals.com—that go into further detail on some of the tweakiest features. (You’ll see references to them sprinkled throughout the book.)

Maybe this idea will save a few trees—and a few back muscles when you try to pick this book up.

About the Outline

MacOS High Sierra: The Missing Manual is divided into six parts, each containing several chapters:

Part I: The macOS Desktop covers everything you see on the screen when you turn on a Mac: folders, windows, icons, the Dock, the Sidebar, Spotlight, Dashboard, Spaces, Mission Control, Launchpad, Time Machine, menus, scroll bars, the Trash, aliases, the

menu, and so on.

menu, and so on.Part II: Programs in macOS is dedicated to the proposition that an operating system is little more than a launchpad for programs—the actual applications you use: email programs, web browsers, word processors, graphics suites, and so on. These chapters describe how to work with applications—how to open them, switch among them, swap data between them, and use them to create and open files. And there’s also, of course, a chapter about Siri.

Part III: The Components of macOS is an item-by-item discussion of the software nuggets that make up this operating system—the 30-ish panels of System Preferences and the 50-some programs in your Applications and Utilities folders.

Part IV: The Technologies of macOS treads in more advanced territory, like networking and file sharing. These chapters also cover the visual talents of the Mac (fonts, printing, graphics) and its multimedia gifts (sound, movies).

Part V: macOS Online covers all the Internet features, including the Mail email program and the Safari web browser; Messages for instant messaging and audio or video chats; Internet sharing; Apple’s free, online iCloud services; and connecting to and controlling your Mac from across the wires—FTP, SSH, VPN, and so on.

Part VI: Appendixes. This book’s appendixes include guidance on installing this operating system, a troubleshooting handbook, a Windows-to-Mac dictionary (to help Windows refugees find the new locations of familiar features in macOS), and a master list of all the keyboard shortcuts and trackpad/mouse gestures on your Mac.

About→These→Arrows

Throughout this book, you’ll find sentences like this one: “Open the System folder→Libraries→Fonts folder.” That’s shorthand for a much longer instruction that directs you to open three nested folders in sequence, like this:

“On your hard drive, you’ll find a folder called System. Open that. Inside the System folder window is a folder called Libraries; double-click to open it. Inside that folder is yet another one called Fonts. Double-click to open it, too.” See Figure 1-1.

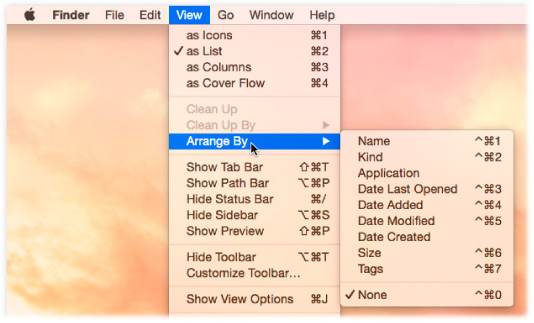

Figure 1-1. If this book says “Choose View→Arrange By→Name,” it’s describing a logical sequence of steps.

In this example, that would mean clicking the View menu, choosing the Arrange By command from it, and then choosing Name from the submenu.

About MissingManuals.com

To get the most out of this book, visit www.missingmanuals.com. Click the “Missing CDs” link—and then this book’s title—to reveal a neat, organized, chapter-by-chapter list of the shareware and freeware mentioned in this book.

The website also offers corrections and updates to the book. (To see them, click the book’s title, and then click View/Submit Errata.) In fact, please submit such corrections and updates yourself! In an effort to keep the book as up-to-date and accurate as possible, each time we print more copies of this book, I’ll make any confirmed corrections you’ve suggested. I’ll also note such changes on the website so you can mark important corrections into your own copy of the book, if you like. And I’ll keep the book current as Apple releases more macOS 10.13 updates.

The Very Basics

To use this book, and indeed to use a Mac, you need to know a few basics. This book assumes you’re familiar with a few terms and concepts:

Clicking. To click means to point the arrow cursor at something on the screen and then—without moving the cursor—press and release the clicker button on the mouse or trackpad. To double-click, of course, means to click twice in rapid succession, again without moving the cursor at all. And to drag means to move the cursor while holding down the mouse button.

When you’re told to

-click something, you click while pressing the

-click something, you click while pressing the  key (which is next to the space bar). Shift-clicking, Option-clicking, and Control-clicking work the same way—just click while pressing the corresponding key.

key (which is next to the space bar). Shift-clicking, Option-clicking, and Control-clicking work the same way—just click while pressing the corresponding key.(There’s also right-clicking. That very important topic is described in depth in “Notes on Right-Clicking”.)

Menus. The menus are the words at the top of your screen:

, File, Edit, and so on. Click one to make a list of commands appear.

, File, Edit, and so on. Click one to make a list of commands appear.Some people click once to open a menu and then, after reading the choices, click again on the one they want. Other people like to press the mouse button continuously after the initial click on the menu title, drag down the list to the desired command, and only then release the mouse button. Either method works fine.

Keyboard shortcuts. If you’re typing along in a burst of creative energy, it’s disruptive to have to grab the mouse to use a menu. That’s why many Mac fans prefer to trigger menu commands by pressing key combinations. For example, in word processors, you can press

-B to produce a boldface word. When you read an instruction like “Press

-B to produce a boldface word. When you read an instruction like “Press  -B,” start by pressing the

-B,” start by pressing the  key, and then, while it’s down, type the letter B, and finally release both keys.

key, and then, while it’s down, type the letter B, and finally release both keys.

Tip

You know what’s really nice? The keystroke to open the Preferences dialog box in every Apple program—Mail, Safari, iMovie, Photos, TextEdit, Preview, and on and on—is always the same: ![]() -comma. Better yet, that standard is catching on in other apps, too, like Word, Excel, and PowerPoint.

-comma. Better yet, that standard is catching on in other apps, too, like Word, Excel, and PowerPoint.

Gestures. A gesture is a swipe across your trackpad (on your laptop, or on an external Apple trackpad) or across the top surface of the Apple Magic Mouse. Gestures have been given huge importance in macOS. “Dialog boxes” contains a handy list of them.

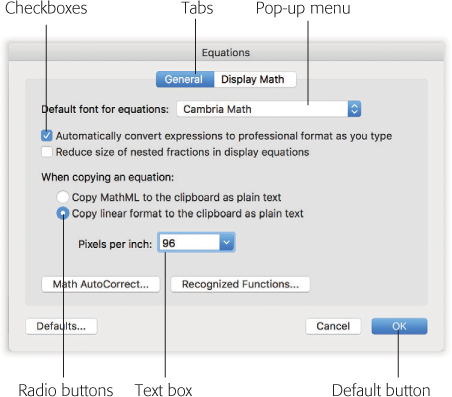

Dialog boxes. See Figure 1-2 for a tour of the onscreen elements you’ll frequently be asked to use, like checkboxes, radio buttons, tabs, and so on.

Figure 1-2. Knowing what you’re doing on the Mac often requires knowing what things are called. Here are some of the most common onscreen elements. They include checkboxes (turn on as many as you like) and radio buttons (only one can be turned on in each grouping).

Pressing Return is usually the same as clicking the default button—the lower-right button that almost always means “OK, I’m done here.”Icons. The colorful inch-tall pictures that appear in your various desktop folders are the graphic symbols that represent each program, disk, and document on your computer. If you click an icon one time, it darkens, indicating that you’ve just highlighted or selected it. Now you’re ready to manipulate it by using, for example, a menu command.

A few more tips on using the Mac keyboard appear at the beginning of Chapter 7. Otherwise, if you’ve mastered this much information, then you have all the technical background you need to enjoy macOS High Sierra: The Missing Manual.

Get macOS High Sierra: The Missing Manual now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.