Chapter 1. Network Industry Trends

Are you new to Software Defined Networking (SDN)? Have you been hung up in the SDN craze for the past several years? Whichever bucket you fall into, do not worry. This book will walk you through foundational topics to start your network programmability and automation journey starting with the rise of SDN. This chapter provides insight to trends in the network industry focused around SDN, its relevance, and its impact in today’s world of networking. We’ll get started by reviewing how Software Defined Networking made it into the mainstream and ultimately led to trends around network programmability and automation.

The Rise of Software Defined Networking

If there was one person that could be credited with all the change that is occurring in the network industry, it would be Martin Casado, who is currently a General Partner and Venture Capitalist at Andreessen Horowitz. Previously, Casado was a VMware Fellow, Senior Vice President, and General Manager in the Networking and Security Business Unit at VMware. He has had a profound impact on the industry, not just from his direct contributions (including OpenFlow and Nicira), but by opening the eyes of large network incumbents and showing that network operations, agility, and manageability must change. Let’s take a look at this in a little more detail.

OpenFlow

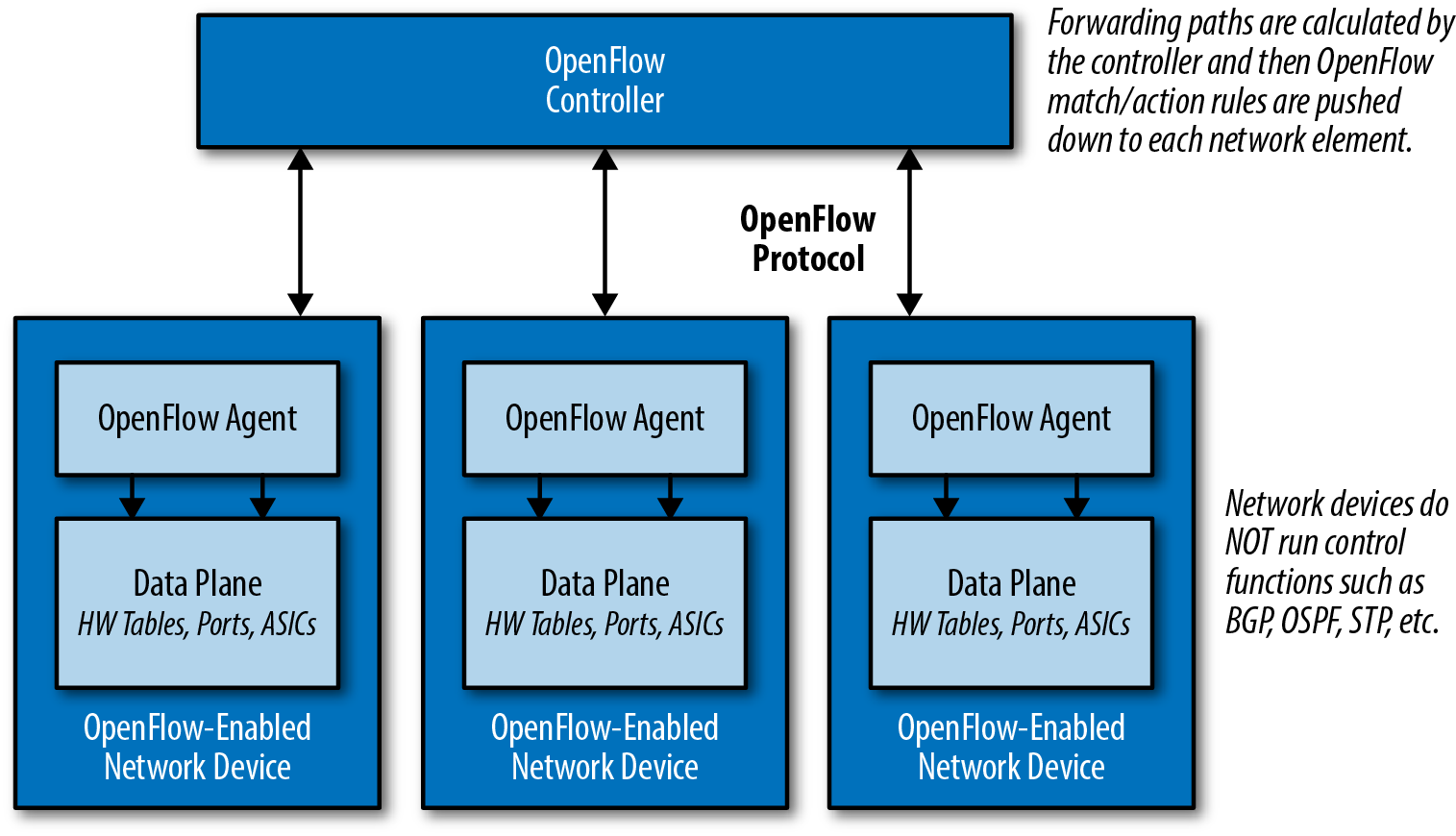

For better or for worse, OpenFlow served as the first major protocol of the Software Defined Networking (SDN) movement. OpenFlow is the protocol that Martin Casado worked on while he was earning his PhD at Stanford University under the supervision of Nick McKeown. OpenFlow is only a protocol that allows for the de-coupling of a network device’s control plane from the data plane (see Figure 1-1). In simplest terms, the control plane can be thought of as the brains of a network device and the data plane can be thought of as the hardware or application-specific integrated circuits (ASICs) that actually perform packet forwarding.

Figure 1-1. Decoupling the control plane and data plane with OpenFlow

What this means is OpenFlow is a low-level protocol that is used to directly interface with the hardware tables (e.g., Forwarding Information Base, or FIB) that instruct a network device how to forward traffic (for example, “traffic to destination 192.168.0.100 should egress port 48”).

Note

OpenFlow is a low-level protocol that manipulates flow tables, thus directly impacting packet forwarding. OpenFlow was not intended to interact with management plane attributes like authentication or SNMP parameters.

Because the tables OpenFlow uses support more than the destination address as compared to traditional routing protocols, there is more granularity (matching fields in the packet) to determine the forwarding path. This is not unlike the granularity offered by Policy Based Routing. Like OpenFlow would do many years later, PBR allows network administrators to forward traffic based on “non-traditional” attributes, like a packet’s source address. However, it took quite some time for network vendors to offer equivalent performance for traffic that was forwarded via PBR, and the final result was still very vendor-specific. The advent of OpenFlow meant that we could now achieve the same granularity with traffic forwarding decisions, but in a vendor-neutral way. It became possible to enhance the capabilities of the network infrastructure without waiting for the next version of hardware from the manufacturer.

Why OpenFlow?

While it’s important to understand what OpenFlow is, it’s even more important to understand the reasoning behind the research and development effort of the original OpenFlow spec that led to the rise of Software Defined Networking.

Martin Casado had a job working for the national government while he was attending Stanford. During his time working for the government, there was a need to react to security attacks on the IT systems (after all, this is the US government). Casado quickly realized that he was able to program and manipulate the computers and servers as he needed. The actual use cases were never publicized, but it was this type of control over endpoints that made it possible to react, analyze, and potentially re-program a host or group of hosts when and if needed.

When it came to the network, it was near impossible to do this in a clean and programmatic fashion. After all, each network device was closed (locked from installing third-party software, as an example) and only had a command-line interface (CLI). Although the CLI was and is still very well known and even preferred by network administrators, it was clear to Casado that it did not offer the flexibility required to truly manage, operate, and secure the network.

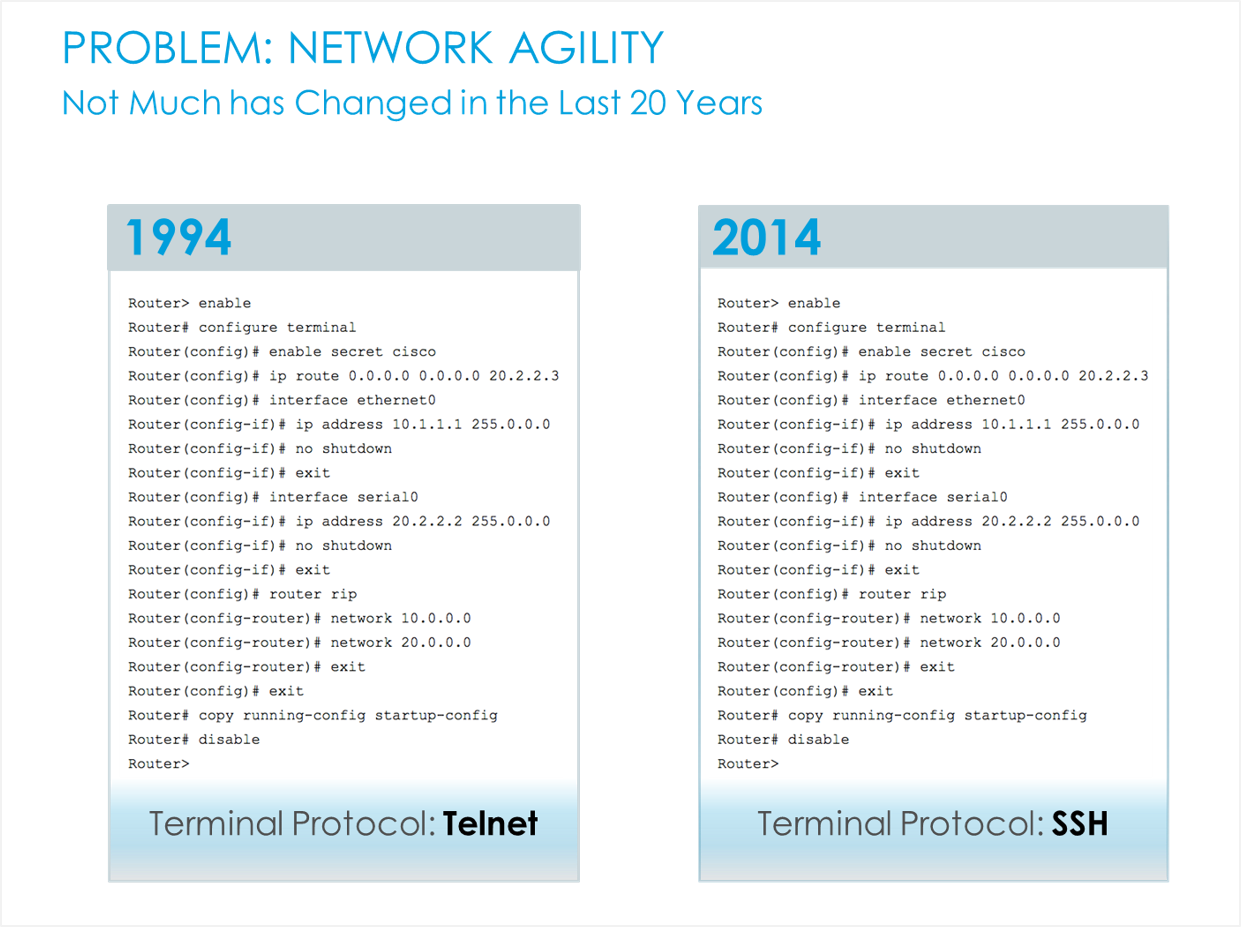

In reality, the way networks were managed had never changed in over 20 years except for the addition of CLI commands for new features. The biggest change was the migration from Telnet to SSH, which was a joke often used by the SDN company Big Switch Networks in their slides, as you can see in Figure 1-2.

Figure 1-2. What’s changed? From Telnet to SSH (source: Big Switch Networks)

All joking aside, the management of networks has lagged behind other technologies quite drastically, and this is what Casado eventually set out to change over the next several years. This lack in manageability is often better understood when other technologies are examined. Other technologies almost always have more modern ways of managing a large number of devices for both configuration management and data gathering and analysis—for example, hypervisor managers, wireless controllers, IP PBXs, PowerShell, DevOps tools, and the list can go on. Some of these are tightly coupled from vendors as commercial software, but others are more loosely aligned to allow for multi-platform management, operations, and agility.

If we go back to the scenario while Casado was working for the government, was it possible to redirect traffic based on application? Did network devices have an API? Was there a single point of communication to the network? The answers were largely no across the board. How could it be possible to program the network to dynamically control packet forwarding, policy, and configuration as easily as it was to write a program and have it execute on an end host machine?

The initial OpenFlow spec was the result of Martin Casado experiencing these types of problems firsthand. While the hype around OpenFlow has died down since the industry is starting to finally focus more on use cases and solutions than low-level protocols, this initial work was the catalyst for the entire industry to do a rethink on how networks are built, managed, and operated. Thank you, Martin.

This also means if it weren’t for Martin Casado, this book would probably not have been written, but we’ll never know now!

What Is Software Defined Networking?

We’ve had an introduction to OpenFlow, but what is Software Defined Networking (SDN)? Are they the same thing, different things, or neither? To be honest, SDN is just like Cloud was nearly a decade ago, before we knew about different types of Cloud, such as Infrastructure as a Service (IaaS), Platform as a Service (PaaS), and Software as a Service (SaaS).

Having reference examples and designs streamlines the understanding of what Cloud was and is, but even before these terms did exist, it could be debated that when you saw Cloud, you knew it. That’s kind of where we are with Software Defined Networking. There are public definitions that exist that state white-box networking is SDN or that having an API on a network device is SDN. Are they really SDN? Not really.

Rather than attempt to provide a definition of SDN, we will cover the technologies and trends that are very often thought of as SDN, and included in the SDN conversation. They include:

-

OpenFlow

-

Network Functions Virtualization

-

Virtual switching

-

Network virtualization

-

Device APIs

-

Network automation

-

Bare-metal switching

-

Data center network fabrics

-

SD-WAN

-

Controller networking

Note

We are intentionally not providing a definition of SDN in this book. While SDN is mentioned in this chapter, our primary focus is on general trends that are often categorized as SDN to ensure you’re aware of each of these trends more specifically.

Of these trends, the rest of the book will focus on network automation, APIs, and peripheral technologies that are critical in understanding how all of the pieces come together in network devices that expose programmatic interfaces with modern automation tools and instrumentation.

OpenFlow

Even though we introduced OpenFlow earlier, we want to highlight a few more key points you should be aware of related to OpenFlow.

One of the major benefits that was supposed to be an outcome of using a protocol like OpenFlow between a controller and network devices was that there would be true vendor independence from the controller software, sometimes referred to as a network operating system (NOS), and the underlying virtual and physical network devices. What has actually happened, though, is that vendors who use OpenFlow in their solution (examples include Big Switch Networks, HP, and NEC) have developed OpenFlow extensions due to the pace of standards and the need to provide unique value-added features that the off-the-shelf version of OpenFlow does not offer. It is yet to be seen if all of the extensions end up making it into future versions of the OpenFlow standard.

When OpenFlow is used, you do gain the benefit to getting more granular with how traffic traverses the network, but with great power comes great responsibility. This is great if you have a team of developers. For example, Google rolled out an OpenFlow-based WAN called B4 that increases efficiency of their WAN to nearly 100%. For most other organizations, the use of OpenFlow or any other given protocol will be less important than what an overall solution offers to the business being supported.

Network Functions Virtualization

Network Functions Virtualization, known as NFV, isn’t a complex concept. It refers to taking functions that have traditionally been deployed as hardware, and instead deploying them as software. The most common examples of this are virtual machines that operate as routers, firewalls, load balancers, IDS/IPS, VPN, application firewalls, and any other service/function.

With NFV, it becomes possible to break down a monolithic piece of hardware that may have cost tens or hundreds of thousands of dollars, with hundreds to thousands of lines of commands, to get it configured into N pieces of software, namely virtual appliances. These smaller devices become much more manageable from an individual device perspective.

Note

The preceding scenario uses virtual appliances as the form factor for NFV-enabled devices. This is merely an example. Deploying network functions as software could come in many forms, including embedded in a hypervisor, as a container, or as an application running atop an x86 server.

It’s not uncommon to deploy hardware that may be needed in three to five years just in case, because it’s too complicated and even more expensive to have gradual upgrades. So not only is hardware an intensive capital cost, it’s only used for the what-if scenarios if growth occurs. Deploying software-based, or NFV, solutions offers a better way to scale out and minimize the failure domain of a network or particular application while using a pay-as-you-grow model. For example, rather than purchasing a single large Cisco ASA, you can gradually deploy Cisco ASAv appliances and pay as you grow. You can also scale out load balancers easily with newer technologies from a company like Avi Networks.

If NFV could offer so much benefit, why haven’t there been more solutions and products that fit into this category deployed in production? There are actually a few different reasons. First, it requires a rethink in how the network is architected. When there is a single monolithic firewall (as an example), everything goes through that firewall—meaning all applications and all users, or if not all, a defined set that you are aware of. In the modern NFV model where there could be many virtual firewalls deployed, there is a firewall per application or tenant as opposed to a single big-box FW. This makes the failure domain per firewall, or any other services appliances, fairly small, and if a change is being made or a new application is being rolled out, no change is required for the other per-application (per-tenant) based firewalls.

On the other hand, in the more traditional world of having monolithic devices, there is essentially a single pane of management for security policy—single CLI or GUI. This could make the failure domain immense, but it does offer administrators streamlined policy management since it’s only a single device being managed. Based on the team or staff supporting these devices, they may opt still for a monolithic approach. That is the reality, but hopefully over time with improved tools that can help with the consumption and management of software-centric solutions, as an industry, we’ll see more deployments leveraging this type of technology. In fact, in a world with modern automated network operations and management, it’ll matter less which architecture is chosen from an operational efficiency perspective as you’ll be able to manage either a single device or a larger quantity of devices in a much more efficient manner.

Aside from management, another factor that plays into this is that many vendors are not actively selling their virtual appliance edition. We’re not saying they don’t have virtual options, but they are usually not the preferred choice of many traditional equipment manufacturers. If a vendor has had a hardware business for the past several years, it’s a drastic shift to a software-led model from a sales and compensation perspective. Because of this, many of these vendors are limiting the performance or features on their virtual appliance-based technology.

As will be seen in many of these technology areas, a major value of NFV is in agility too. Eliminating hardware decreases the time to provision new services by removing the time needed to rack, stack, cable, and integrate into an existing environment. Leveraging a software approach, it becomes as fast as deploying a new virtual machine into the environment, and an inherent benefit of this approach is being able to clone and back up the virtual appliance for further testing, for example in disaster recovery (DR) environments.

Finally, when NFV is deployed, it eliminates the need to route traffic through a specific physical device in order to get the required service.

Virtual switching

The more common virtual switches on the market these days include the VMware standard switch (VSS), VMware distributed switch (VDS), Cisco Nexus 1000V, Cisco Application Virtual Switch (AVS), and the open source Open vSwitch (OVS).

These switches every so often get wrapped into the SDN discussion, but in reality they are software-based switches that reside in the hypervisor kernel providing local network connectivity between virtual machines (and now containers). They provide functions such as MAC learning and features like link aggregation, SPAN, and sFlow just like their physical switch counterparts have been doing for years. While these virtual switches are often found in more comprehensive SDN and network virtualization solutions, by themselves they are a switch that just happens to be running in software. While virtual switches are not a solution on their own, they are extremely important as we move forward as an industry. They’ve created a new access layer, or new edge, within the data center. No longer is the network edge the physical top-of-rack (TOR) switch that is hardware-defined with limited flexibility (in terms of feature/function development). Since the new edge is software-based through the use of virtual switches, it offers the ability to more rapidly create new network functions in software, and thus, it is possible to distribute policy more easily throughout the network. As an example, security policy can be deployed to the virtual switch port that is nearest to the actual endpoint, be it a virtual machine or container, to further enhance the security of the network.

Network virtualization

Solutions that are categorized as network virtualization have become synonymous with SDN solutions. For purposes of this section, network virtualization refers to software-only overlay-based solutions. The popular solutions that fall into this category are VMware’s NSX, Nuage’s Virtual Service Platform (VSP), and Juniper’s Contrail.

A key characteristic of these solutions is that an overlay-based protocol such as Virtual eXtensible LAN (VxLAN) is used to build connectivity between hypervisor-based virtual switches. This connectivity and tunneling approach provides Layer 2 adjacency between virtual machines that exist on different physical hosts independent of the physical network, meaning the physical network could be Layer 2, Layer 3, or a combination of both. The result is a virtual network that is decoupled from the physical network and that is meant to provide choice and agility.

Note

It’s worth pointing out that the term overlay network is often used in conjunction with the term underlay network. For clarity, the underlay is the underlying physical network that you physically cable up. The overlay network is built using a network virtualization solution that dynamically creates tunnels between virtual switches within a data center. Again, this is in the context of a software-based network virtualization solution. Also note that many hardware-only solutions are now being deployed with VxLAN as the overlay protocol to establish Layer 2 tunnels between top-of-rack devices within a Layer 3 data center.

While the overlay is an implementation detail of network virtualization solutions, these solutions are much more than just virtual switches being stitched together by overlays. These solutions are usually comprehensive, offering security, load balancing, and integrations back into the physical network all with a single point of management (i.e., the controller). Oftentimes these solutions offer integrations with the best-of-breed Layer 4–7 services companies as well, offering choice as to which technology could be deployed within network virtualzation platforms.

Agility is also achieved thanks to the central controller platform, which is used to dynamically configure each virtual switch, and services appliances as needed. If you recall, the network has lagged behind operationally due to the CLI that is pervasive across all vendors in the physical world. In network virtualization, there is no need to configure virtual switches manually, as each solution simplifies this process by providing a central GUI, CLI, and also an API where changes can be made programmatically.

Device APIs

Over the past several years, vendors have begun to realize that just offering a standard CLI was not going to cut it anymore and that using a CLI has severely held back operations. If you have ever worked with any programming or scripting language, you can probably understand that. For those that haven’t, we’ll talk more about this in Chapter 7.

The major pain point is that scripting with legacy or CLI-based network devices does not return structured data. This meant data would be returned from the device to a script in a raw text format (i.e., the output of a show version) and then the individual writing the script would need to parse that text to extract attributes such as uptime or operating system version. When the output of show commands changed even slightly, the scripts would break due to incorrect parsing rules. While this approach is all administrators have had, automation was technically possible, but now vendors are gradually migrating to API-driven network devices.

Offering an API eliminates the need to parse raw text, as structured data is returned from a network device, significantly reducing the time it takes to write a script. Rather than parsing through text to find the uptime or any other attribute, an object is returned providing exactly what is needed. Not only does it reduce the time to write a script, lowering the barrier to entry for network engineers (and other non-programmers), but it also provides a cleaner interface such that professional software developers can rapidly develop and test code, much like they operate using APIs on non-network devices. “Test code” could mean testing new topologies, certifying new network features, validating particular network configurations, and more. These are all things that are done manually today and are very time consuming and error prone.

One of the first more popular APIs in the network scene was that by Arista Networks. Its API is called eAPI, which is HTTP-based API that uses JSON-encoded data. Don’t worry, HTTP-based APIs and JSON will be covered in chapters to follow, starting with Chapter 5. Since Arista, we’ve seen Cisco announce APIs such as Nexus NX-API and NETCONF/RESTCONF on particular platforms and a vendor like Juniper, which has had an extensible NETCONF interface all along but hasn’t publicly drawn too much attention to it. It’s worth noting that nearly every vendor out there has some sort of API these days.

This topic will be covered in much more detail in Chapter 7.

Network automation

As APIs in the network world continue to evolve, more interesting use cases for taking advantage of them will also continue to emerge. In the near term, network automation is a prime candidate for taking advantage of the programmatic interfaces being exposed by modern network devices that offer an API.

To put it in greater context, network automation is not just about automating the configuration of network devices. It is true that is the most common perception of network automation, but using APIs and programmatic interfaces can automate and offer much more than pushing configuration parameters.

Leveraging an API streamlines the access to all of the data bottled up in network devices. Think about data such as flow level data, routing tables, FIB tables, interface statistics, MAC tables, VLAN tables, serial numbers—the list can go on and on. Using modern automation techniques that in turn leverage an API can quickly aid in the day-to-day operations of managing networks for data gathering and automated diagnostics. On top of that, since an API is being used that returns structured data, as an administrator, you will have the ability to display and analyze the exact data set you want and need, even coming from various show commands, ultimately reducing the time it takes to debug and troubleshoot issues on the network. Rather than connecting to N routers running BGP trying to validate a configuration or troubleshoot an issue, you can use automation techniques to simplify this process.

Additionally, leveraging automation techniques leads to a more predictable and uniform network as a whole. You can see this by automating the creation of configuration files, automating the creation of a VLAN, or automating the process of troubleshooting. It streamlines the process for all users supporting a given environment instead of having each network administrator having their own best practice.

The various types of network automation will be covered in Chapter 2 in much greater depth.

Bare-metal switching

The topic of bare-metal switching is also often thought of as SDN, but it’s not. Really, it isn’t! That said, in our effort to give an introduction to the various technology trends that are perceived as SDN, it needs to be covered. If we rewind to 2014 (and even earlier), the term used to describe bare-metal switching was white-box or commodity switching. The term has changed, and not without good reason.

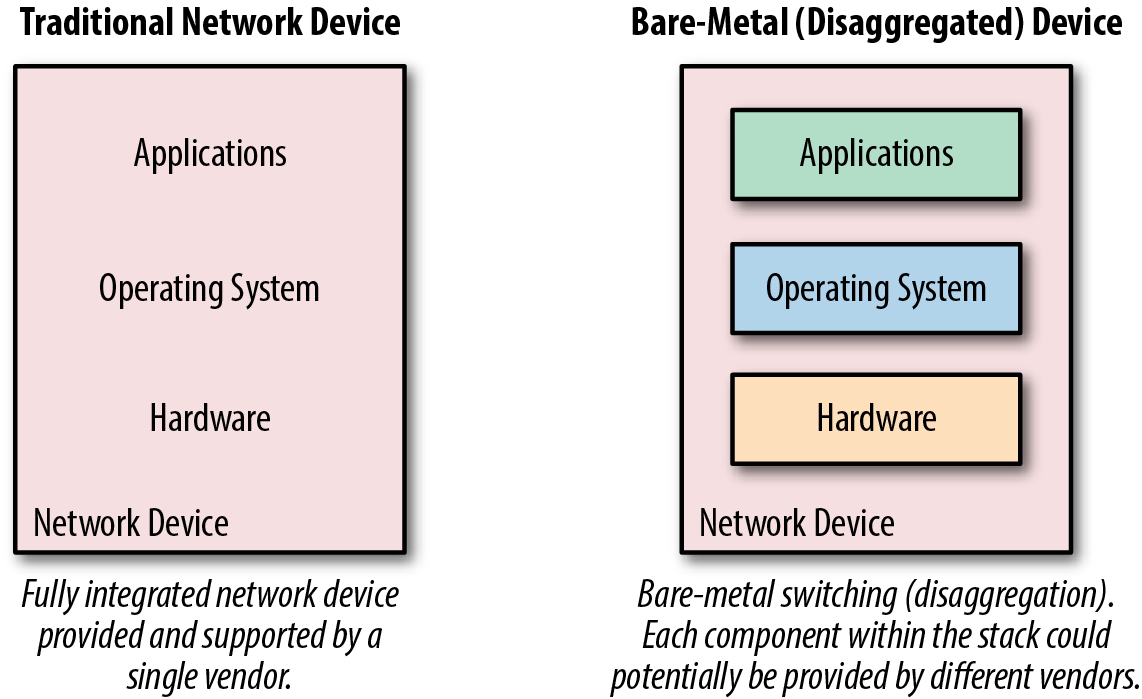

Before we cover the change from white-box to bare-metal, it’s important to understand what this means at a high level since it’s a massive change in how network devices are thought of. Network devices for the last 20 years were always bought as a physical device—these physical devices came as hardware appliances, an operating system, and features/applications that you can use on the system. These components all came from the same vendor.

In the white-box and bare-metal network devices, the device looks more like an x86 server (see Figure 1-3). It allows the user to disaggregate each of the required components, making it possible to purchase hardware from one vendor, purchase an operating system from another, and then load features/apps from other vendors or even the open source community.

White-box switching was a hot topic for a period of time during the OpenFlow hype, since the intent was to commoditize hardware and centralize the brains of the network in an OpenFlow controller, otherwise now known as an SDN controller. And in 2013, Google announced they had built their own switches and were controlling them with OpenFlow! This was the topic of a lot of industry conversations at the time, but in reality, not every end user is Google, so not every user will be building their own hardware and software platforms.

In parallel to these efforts, we saw the emergence of a few companies that were solely focused on providing solutions around white-box switching. They include Big Switch Networks, Cumulus Networks, and Pica8. Each of them offers software-only solutions, so they still need hardware that their software will run on to provide an end-to-end solution. Initially, these white-box hardware platforms came from Original Direct Manufacturers (ODM) such as Quanta, Super Micro, and Accton. If you’ve been in the network industry, more than likely you’ve never even heard of those vendors.

Figure 1-3. A look at traditional and bare-metal switching stacks

It wasn’t until Cumulus and Big Switch announced partnerships with companies including HP and Dell that the industry started to shift from calling this trend white-box to bare-metal, since now name-brand vendors were supporting third-party operating systems from the likes of Big Switch and Cumulus Networks on their hardware platforms.

There still may be confusion on why bare-metal is technically not SDN, since a vendor like Big Switch plays in both worlds. The answer is simple. If there is a controller integrated with the solution using a protocol such as OpenFlow (it does not have to be OpenFlow), and it is programmatically communicating with the network devices, that gives it the flavor of Software Defined Networking. This is what Big Switch does—they load software on the bare-metal/white-box hardware running an OpenFlow agent that then communicates with the controller as part of their solution.

On the other hand, Cumulus Networks provides a Linux distribution purpose-built for network switches. This distribution, or operating system, runs traditional protocols such as LLDP, OSPF, and BGP, with no controller requirement whatsoever, making it more comparable, and compatible, to non-SDN based network architectures.

With this description it should be evident that Cumulus is a network operating system company that runs their software on bare-metal switches while Big Switch is a bare-metal-based SDN company requiring the use of their SDN controller, but also leverages third-party, bare-metal switching infrastructure.

In short, bare-metal/white-box switching is about disaggregation and having the ability to purchase network hardware from one vendor and load software from another, should you choose to do so. In this case, administrators are offered the flexibility to change designs, architectures, and software, without swapping out hardware, just the underlying operating system.

Data center network fabrics

Have you ever faced the situation where you could not easily interchange the various network devices in a network even if they were all running standard protocols such as Spanning Tree or OSPF? If you have, you are not alone. Imagine having a data center network with a collapsed core and individual switches at the top of each rack. Now think about the process that needs to happen when it’s time for an upgrade.

There are many ways to upgrade networks like this, but what if it was just the top-of-rack switches that needed to be upgraded and in the evaluation process for new TOR switches, it was decided a new vendor or platform would be used? This is 100% normal and has been done time and time again. The process is simple—interconnect the new switches to the existing core (of course, we are assuming there are available ports in the core) and properly configure 802.1Q trunking if it’s a Layer 2 interconnect or configure your favorite routing protocol if it’s a Layer 3 interconnect.

Enter data center network fabrics. This is where the thought process around data center networks has to change.

Data center network fabrics aim to change the mindset of network operators from managing individual boxes one at a time to managing a system in its entirety. If we use the earlier scenario, it would not be possible to swap out a TOR switch for another vendor, which is just a single component of a data center network. Rather, when the network is deployed and managed as a system, it needs to be thought of as a system. This means the upgrade process would be to migrate from system to system, or fabric to fabric. In the world of fabrics, fabrics can be swapped out when it’s time for an upgrade, but the individual components within the fabric cannot be—at least most of the time. It may be possible when a specific vendor is providing a migration or upgrade path and when bare-metal switching (only replacing hardware) is being used. A few examples of data center network fabrics are Cisco’s Application Centric Infrastructure (ACI), Big Switch’s Big Cloud Fabric (BCF), or Plexxi’s fabric and hyper-converged network.

In addition to treating the network as a system, a few other common attributes of data center networking fabrics are:

-

They offer a single interface to manage or configure the fabric, including policy management.

-

They offer distributed default gateways across the fabric.

-

They offer multi-pathing capabilities.

-

They use some form of SDN controller to manage the system.

SD-WAN

One of the hottest trends in Software Defined Networking over the past two years has been Software Defined Wide Area Networking (SD-WAN). Over the past few years, a growing number of companies have been launched to tackle the problem of Wide Area Networking. A few of these vendors include Viptela (most recently acquired by Cisco), CloudGenix, VeloCloud, Cisco IWAN, Glue Networks, and Silverpeak.

The WAN had not seen a radical shift in technology since the migration from Frame Relay to MPLS. With broadband and internet costs being a fraction of what costs are for equivalent private line circuits, there has been an increase in leveraging site-to-site VPN tunnels over the years, laying the groundwork for the next big thing in WAN.

Common designs for remote offices typically include a private (MPLS) circuit and/or a public internet connection. When both exist, internet is usually used as backup only, specifically for guest traffic, or for general data riding back over a VPN to corporate while the MPLS circuit is used for low-latency applications such as voice or video communications. When traffic starts to get divided between circuits, this increases the complexity of the routing protocol configuration and also limits the granularity of how to route to the destination address. The source address, application, and real-time performance of the network is usually not taken into consideration in decisions about the best path to take.

A common SD-WAN architecture that many of the modern solutions use is similar to that of network virtualization used in the data center, in that an overlay protocol is used to interconnect the SD-WAN edge devices. Since overlays are used, the solution is agnostic to the underlying physical transport, making SD-WAN functional over the internet or a private WAN. These solutions often ride over two or more internet circuits at branch sites, fully encrypting traffic using IPSec. Additionally, many of these solutions constantly measure the performance of each circuit in use being able to rapidly fail over between circuits for specific applications even during brownouts. Since there is application layer visibility, administrators can also easily pick and choose which application should take a particular route. These types of features are often not found in WAN architectures that rely solely on destination-based routing using traditional routing protocol such as OSPF and BGP.

From an architecture standpoint, the SD-WAN solutions from the vendors mentioned earlier like Cisco, Viptela, and CloudGenix also typically offer some form of zero touch provisioning (ZTP) and centralized management with a portal that exists on premises or in the cloud as a SaaS-based application, drastically simplifying management and operations of the WAN going forward.

A valuable by-product of using SD-WAN technology is that it offers more choice for end users since basically any carrier or type of connection can be used on the WAN and across the internet. In doing so, it simplifies the configuration and complexity of carrier networks, which in turn will allow carriers to simplify their internal design and architecture, hopefully reducing their costs. Going one step further from a technical perspective, all logical network constructs such as Virtual Routing and Forwarding (VRFs) would be managed via the controller platform user interface (UI) that the SD-WAN vendor provides, again eliminating the need to wait weeks for carriers to respond to you when changes are required.

Controller networking

When it comes to several of these trends, there is some overlap, as you may have realized. That is one of the confusing points when you are trying to understand all of the new technology and trends that have emerged over the last few years.

For example, popular network virtualization platforms use a controller, as do several solutions that fall into the data center network fabric, SD-WAN, and bare-metal switch categories too. Confusing? You may be wondering why controller-based networking has been broken out by itself. In reality, it oftentimes is just characteristic and a mechanism to deliver modern solutions, but not all of the previous trends cover all of what controllers can deliver from a technology perspective.

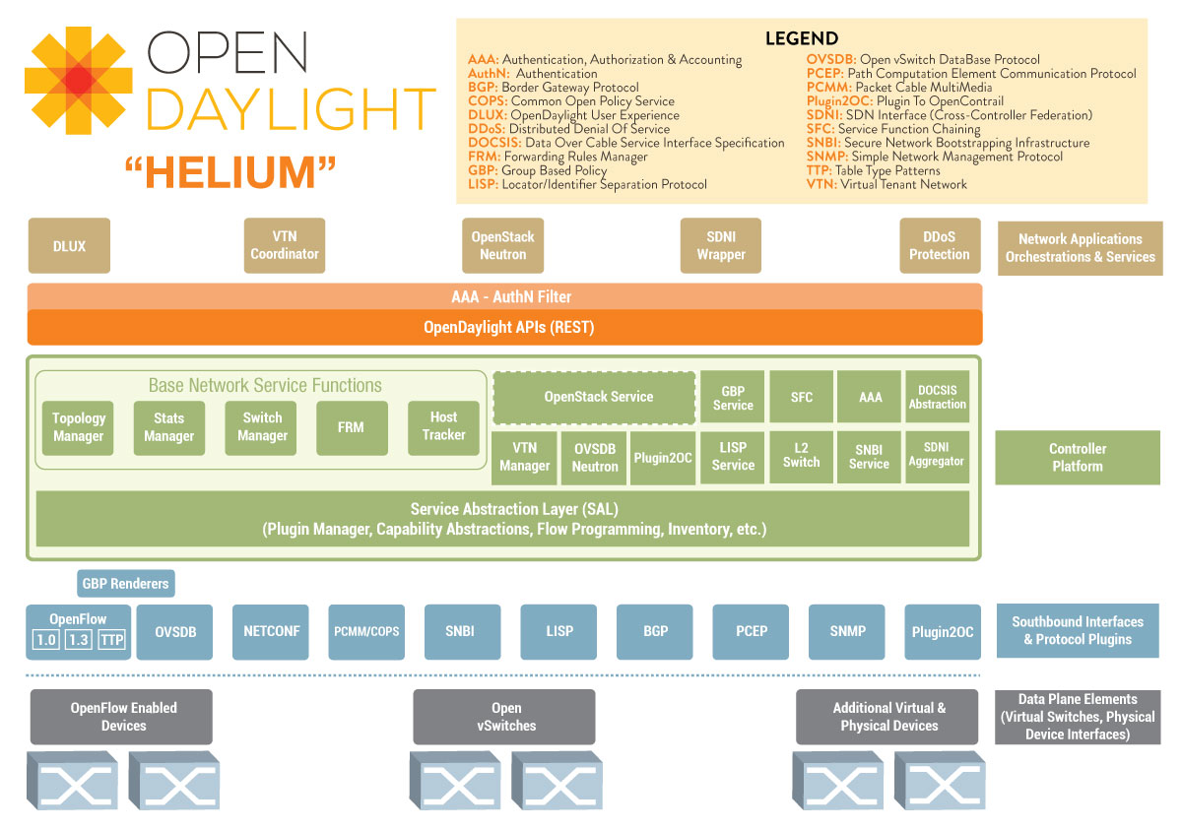

For example, a very popular open source SDN controller is OpenDaylight (ODL), as shown in Figure 1-4. ODL, as with many other controllers, is a platform, not a product. They are platforms that can offer specialized applications such as network virtualization, but they can also be used for network monitoring, visibility, tap aggregation, or any other function in conjunction with applications that sit on top of the controller platform. This is the core reason why it’s important to understand what controllers can offer above and beyond being used for more traditional applications such as fabrics, network virtualization, and SD-WAN.

Figure 1-4. OpenDaylight architecture

Summary

There you have it: an introduction to the trends and technologies that are most often categorized as Software Defined Networking, paving the path into better network operations through network programmability and automation. Dozens of SDN startups were created over the past seven years, millions in VC money invested, and billions spent on acquisitions of these companies. It’s been unreal, and if we break it down one step further, it’s all with the common goal of leveraging software principles and technology to offer greater power, control, agility, and choice to the users of the technology while increasing the operational efficiencies.

In Chapter 2, we’ll take a look at network automation and dive deeper into the various types of automation, some common protocols and APIs, and how automation has started to evolve in the last several years.

Get Network Programmability and Automation now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.