Chapter 1. The Practice of Product Management

I recently asked Pradeep GanapathyRaj, director of product management at Yammer, what he wished that every new product management hire understood about their responsibilities. Here are his answers:

Bringing out the best in the people on your team

Working with people outside of your immediate team, who are not directly incentivized to work with you

Dealing with ambiguity

On his third point, he added: “The skill of actually figuring out what you need is probably as important as what you do after you figure it out.”

Perhaps the most striking thing about these answers is that none of them are about product, per se. Although many people are drawn to product management by the promise of “building products that people love,” the day-to-day practice of product management involves much less actual building than it does supporting, facilitating, and communicating. In this chapter, we discuss the actual, real-world practice of product management, and address a few common traps that product managers fall into when their expectations of the role don’t line up with the reality.

What Is Product Management?

So, what exactly does a product manager do all day, anyhow?

The answer to that question depends on a lot of things. At a small startup, you might find a product manager cobbling together product mock-ups, scheduling check-in points with contract developers, and conducting informal interviews with potential users. At a medium-sized technology company, you might find a product manager running planning meetings with a team of designers and developers, negotiating product roadmaps with senior executives, and working with their colleagues in sales and customer service to understand and prioritize user needs. At a large enterprise organization, you might find a product manager rewriting feature requests as “user stories,” requesting specific data from their colleagues who work in analytics or insights, and attending a whole lot of meetings.

In other words, if you are working as a product manager, you will probably find yourself doing lots of different things at different times—and what exactly those things are can change at a moment’s notice. However, there are a few consistent themes that unite the work of product management across job titles, industries, business models, and company sizes:

- You have lots of responsibility but little authority

Did your designers and developers miss a launch deadline? That is your responsibility. Did the product you manage fail to meet its quarterly goals? That’s also your responsibility. As a product manager, you are the person who is ultimately responsible for the success or failure of your product—regardless of how well supported that product might be by the rest of the organization.

Working in a position of high responsibility is challenging enough, but to further complicate matters, product managers rarely have any direct organizational authority. Is there a designer on your product team who’s showing up late to meetings? An engineer whose attitude is proving toxic to the team at large? These are your problems to solve, but you can’t solve them with the bludgeon of “because I said so” or “you’re fired.” You must lead through influence, not authority, which requires developing an entirely different set of skills and approaches.

- If it needs to get done, it’s part of your job

-

“But—that’s not my job!” is a phrase rarely uttered by successful product managers. Regardless of whether it falls neatly into the boundaries of your written job description, you are responsible for doing whatever needs to get done to ensure the success of your team and your product. This might mean coming in early to bring coffee and breakfast to an overworked product team. It might mean insisting that you get face-to-face time with a senior executive to resolve some ambiguity around your team’s goals. And it might mean calling in a favor from elsewhere in the organization if your team simply doesn’t have the capacity to do what’s needed on its own.

-

If you work as a “product manager” at a very early-stage startup, you might find yourself spending most of your time doing work that feels like it has very little to do with “product management” at all. Product managers I’ve known at early-stage startups have found themselves working as ad hoc community managers, HR leads, UX designers, and office managers. If it needs to be done, and it isn’t anyone else’s job, then—surprise!—it’s your job. Even at large enterprise companies, there will almost certainly be times when you need to step up and do something that is not officially part of your job. And, because you are held responsible for the performance of your team and your product, “that wasn’t my job” plays as well at a Fortune 50 corporation as it does at a five-person startup.

-

To make this even more challenging, most of the things you will need to get done as a product manager are not things you can do alone. You do not have the luxury of disappearing for a few weeks, reading a bunch of books, and returning fully skilled up and ready to single-handedly deliver a product. You will need to ask for support, guidance, and hard work from the people around you—often people outside of your immediate team, who might have no obvious reason to help you out.

- You are in the middle

As a product manager, much of your job comes down to translating between the needs, perspectives, and skill sets of your stakeholders and users. This would be challenging enough if your only goal were to synthesize these far-flung data points into an actionable product plan. But as a product manager, you also sit in the middle of the people who hold these needs, perspectives, and skill sets. You must understand their communication styles, their sensitivities, and the differences between what they say and what they mean.

Even at organizations that are highly structured and systematized, or that claim to be impartial and “data-driven,” it is inevitable that at some point you will find yourself navigating a tangled web of unspoken resentment and unresolved conflict. Others might be able to keep their heads down and “just do their work,” but making connections between messy, real-world people is your work.

What Is Not Product Management?

Product management can be many different things, but it is not everything. Here are a few consistent—and for some people, consistently disappointing—realities of what product management is not:

- You are not the boss

-

I’ve often seen the role of product manager described as the “mini-CEO” of a product. Unfortunately, most of the product managers I’ve seen act like a “mini-CEO” are more interested in the status of this honorary distinction than they are in its responsibility. Yes, as a product manager, you are responsible for the success or failure of your product. But, for you to meet this responsibility, you are entirely dependent upon the trust and hard work of your team. That trust can be easily squandered if you carry yourself like a big important boss, ordering people around and failing to show the same in-the-trenches commitment that you’re expecting from the other members of your team.

- You are not actually building the product yourself

-

For some people, “product management” evokes visions of brilliant inventors and tinkerers, toiling away to bring their game-changing idea to the masses. If you like to be the person actually building things with your hands, you might find yourself deeply frustrated by the connective and facilitative nature of product management. Furthermore, what feels like a good-natured wish to get into the weeds of technical and design decisions might come off as infuriating micromanagement to the people actually tasked with building the product you manage.

-

This absolutely does not mean that you should take zero interest in your product team’s technical and design decisions. Taking a genuine interest in the work of your colleagues is one of the most important things you can do as a product manager. But product management often poses a particular challenge to those who come from the “never mind, I’ll just go do it myself” school of problem-solving. If you, like me, are the kind of person who absolutely hated “group projects” in school and sought to take on as much work as possible for yourself, product management is likely to teach you difficult-yet-important lessons about trust, collaboration, and delegating.

- You can’t wait around until somebody tells you what to do

As I learned on my first day as a product manager, it’s exceptionally rare that you will be given clear guidelines and instructions in this role. Larger companies, especially larger companies like Amazon and Google that have a mature product management practice, are more likely than other companies to have a well-defined set of expectations around the product manager role. But even at those companies, you will have your work cut out for you figuring out what you should do, who you should talk to, and discovering the “unknown unknowns” that are unique to your product and team.

If you’re unclear about a directive coming down from senior leadership, you can’t sit around waiting for them to clarify it. If you see something in a mock-up that you think will be a problem, you can’t wait until somebody else catches it. Just as you need to get out ahead of identifying the work that needs to be done, you also need to get out ahead of any disconnects in communication or understanding that might harm your product or your team, and be relentless about resolving them.

What Is the Profile of a Great Product Manager?

Some organizations are well known for favoring a certain “profile” for product management candidates. Amazon, for example, looks for MBAs. Google, on the other hand, prefers candidates with a computer science degree from Stanford. Generally speaking, the “classic” profile for a product manager is either a technical person with some business savvy, or a business-savvy person who will not annoy the hell out of developers.

Although there are plenty of product managers who fit this profile to some degree, some of the very best product managers I’ve met—including product managers who cut their teeth at Amazon and Google—don’t fit any “classic” profile. The truth is, great product managers can come from anywhere. Some of the best product managers I’ve met have backgrounds in music, politics, nonprofits, theater, marketing—you name it. Generally speaking, they are people who like to solve interesting problems, learn new things, and work with smart people.

Great product managers are the sum of their experiences, the challenges they’ve faced, and the people they’ve worked with. They are constantly evolving and adapting their own practice to meet the specific needs of their current team and organization.

When I consult with organizations that are looking to identify internal candidates for PM roles, I often ask a few people to draw out a diagram of how information travels within the company—not a formal org chart, just an informal sketch of how people communicate with each other. Without fail, a few people continuously show up smack in the middle—these people are the information brokers, the connectors, the expansive thinkers who are actively seeking out new perspectives. These people rarely fit the “traditional” profile of a product manager, and, in many cases, they are entirely nontechnical. But these are the people who have already proven their capability at difficult but critical connective skills, and have demonstrated the initiative to take on this kind of work without much formal recognition.

What Is the Profile of a Bad Product Manager?

Although great product managers rarely fit a single profile, bad product managers are quite consistent. There are some bad product manager archetypes that seem to show up in nearly every kind of organization:

- The Jargon Jockey

The Jargon Jockey wants you to know that the approach you’re describing might make sense if you were working in a hybrid Scrumban methodology, but is simply unacceptable to a certified PSM III Scrum Master. (If you had to look any of that up, the Jargon Jockey is shocked by your incompetence—how did you even get this job in the first place?) The Jargon Jockey is appalled that you haven’t heard of Arie van Bennekum—one of the signers of the Agile Manifesto! The Jargon Jockey defines words you haven’t heard with other words you haven’t heard and seems to use those words more and more when there’s a high-stakes disagreement playing out.

- The Steve Jobs Acolyte

The Steve Jobs Acolyte Thinks Differently™. The Steve Jobs Acolyte likes to lean back in chairs and ask big, provocative questions. The Steve Jobs Acolyte would like to remind you that people didn’t know that they wanted the iPhone, either. The Steve Jobs Acolyte doesn’t want to build a faster horse. The Steve Jobs Acolyte wouldn’t say that your users are stupid—at least, not exactly—but they are definitely not visionaries like the Steve Jobs Acolyte.

- The Hero Product Manager

Have no fear, the Hero Product Manager is here with an amazing idea that will save the whole company. The Hero Product Manager is not particularly interested in hearing why this idea might not work, or that it’s already been discussed and explored a million times. Did you hear about what the Hero Product Manager did at their last company? They pretty much built the whole thing single-handedly, or at least the good parts. And yet, the people at this company just never seem to give the Hero Product Manager the resources or support they need to deliver on all those amazing promises.

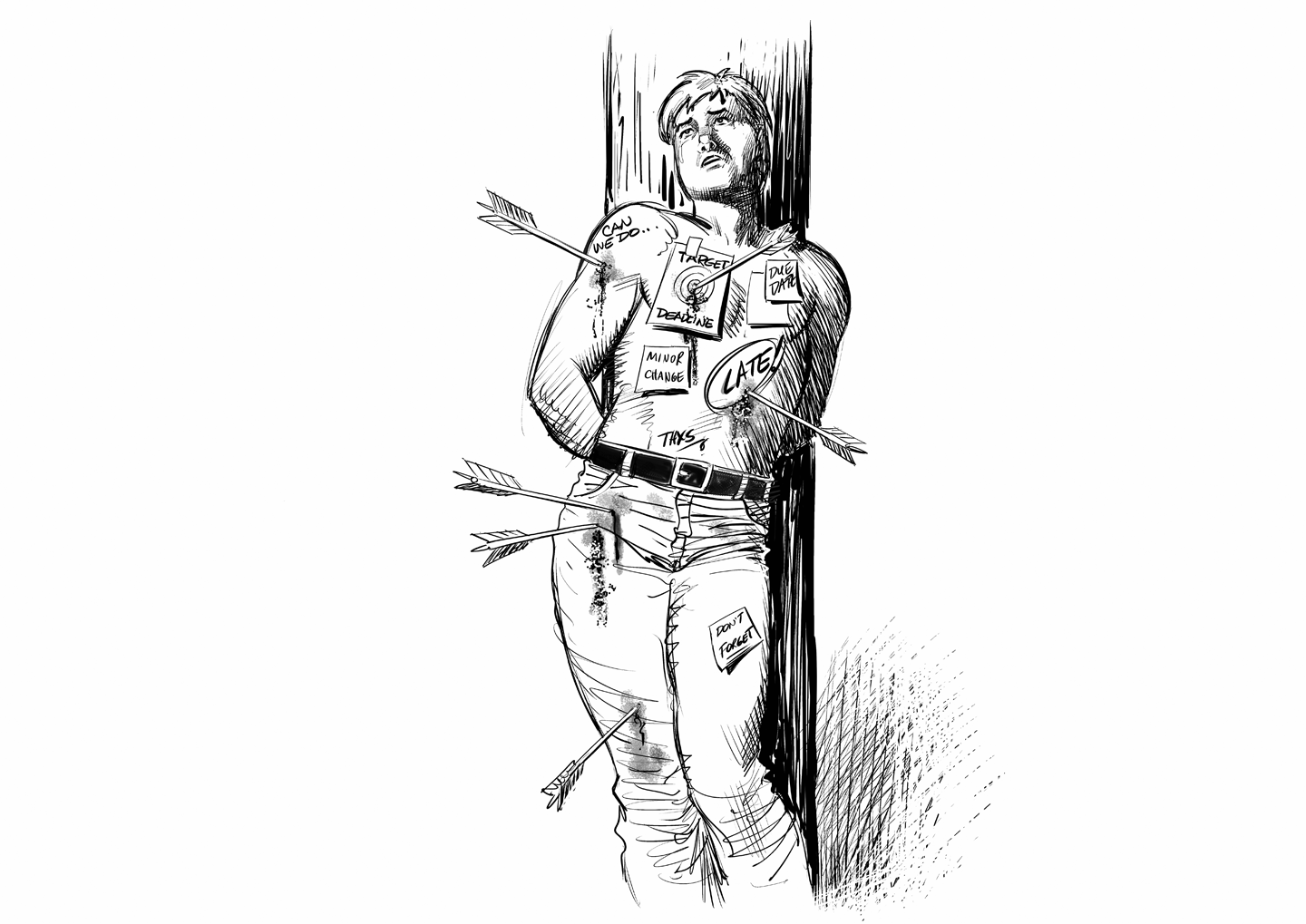

- The Product Martyr

Fine! The Product Martyr (Figure 1-1) will do it. If the product didn’t launch on time or didn’t meet its goals, the Product Martyr takes complete and unequivocal responsibility for screwing everything up (again). The Product Martyr says it’s no big deal that they pick up coffee for the whole team every morning, but the way they place the Starbucks tray down on their desk seems just a liiiiiiiiittle more emphatic than it needs to be. The Product Martyr says repeatedly that they’ve put this job ahead of everything else in their life, and yet they seem outraged and overburdened every time you come to them with a new question or concern.

- The Nostalgic Engineer

The Nostalgic Engineer would rather be writing code than sitting in all these meetings. Did you know that the Nostalgic Engineer used to write code? Really good code, too, before there was all this “jquery” nonsense. The Nostalgic Engineer is happy for the product team to work on whatever that team thinks is most fun. Did the Nostalgic Engineer mention that they would rather be writing code than be stuck in this stupid meeting? No offense, of course.

Figure 1-1. The Product Martyr, in the wild

These patterns are shockingly easy to fall into—I’ve definitely fallen into all of them at one point or another in my career. Why? Because by and large they are driven not by malice or incompetence but by insecurity. Product management can be a brutal and relentless trigger for insecurity, and insecurity can bring out the worst in all of us.

Because product management is a connective and facilitative role, the actual value product managers bring to the table can be very difficult to quantify. Your developer wrote 10,000 lines of code. Your designer created a tactile, visual universe that wowed everybody in the room. Your CEO is the visionary who led the team to success. Just what did you do, exactly?

This question—and the urge to defensively demonstrate value—can lead to some epic acts of unintentional self-sabotage. Insecure product managers might begin to make big, awkward public displays of their contributions (the Product Martyr). They might begin speaking in gibberish to prove that product management is a real thing that is really complicated and important (the Jargon Jockey). They might even start devaluing their own contributions to the team for the sake of showing that they could be doing higher-status work if they wanted to (the Nostalgic Engineer).

For product managers, the value you create will be largely manifest in the work of your team. The best product managers I’ve met are those whose teams use phrases like “I would trust that person with my life” and, “That person makes me feel excited to show up for work in the morning.” If you’re starting to feel insecure about your work, talk to your team and see what you can do to better contribute to their success. But don’t let insecurity turn you into a bad product manager—and please, please, don’t quote Steve Jobs in a meeting or job interview.

Summary: Sailing the Seas of Ambiguity

No matter how many books you’ve read (including this one), how many articles you’ve scrolled through, or how many conversations you’ve had with working product managers, there will always be new and unexpected challenges in this line of work. Do your best to remain open to these challenges and, if possible, enjoy the fact that the ambiguity around your role means that you are likely to learn lots of entirely new things.

Your Checklist:

Accept that being a product manager means that you are going to have to do lots of different things. Don’t become upset if your day-to-day work is not visionary and important-seeming, so long as it is contributing to the goals of your team.

Find ways to align, motivate, and inspire your team that do not require formal organizational authority.

Be proactive about seeking out ways that you can help contribute to the success of your product and your team. Nobody is going to tell you exactly what to do all the time.

Be a connector between teams and roles.

Get out ahead of potential miscommunications and misalignments, no matter how inconsequential they might seem in the moment.

Don’t get too hung up on the “typical profile” of a successful product manager. Successful product managers can come from anywhere.

Don’t let insecurity turn you into the caricature of a bad product manager! Resist the urge to defensively show off your knowledge or skills.

Get Product Management in Practice now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.