Chapter 4. Using the Transpiler

We’ve been using the QuantumCircuit class to represent quantum programs, and the purpose of quantum programs is to run them on real devices and get results from them. When programming, we usually don’t worry about the device-specific details and instead use high-level operations. But most devices (and some simulators) can carry out only a small set of operations and can perform multiqubit gates only between certain qubits. This means we need to transpile our circuit for the specific device we’re running on.

The transpilation process involves converting the operations in the circuit to those supported by the device and swapping qubits (via swap gates) within the circuit to overcome limited qubit connectivity. Qiskit’s transpiler does this job, as well as some optimization to reduce the circuit’s gate count where it can.

Quickstart with Transpile

In this section, we’ll show you how to use the transpiler to get your circuit device-ready. We’ll give a brief overview of the transpiler’s logic and how we can get the best results from it.

The only required argument for transpile is the QuantumCircuit we want to transpile, but if we want transpile to do something interesting, we’ll need to tell it what we want it to do. The easiest way to get your circuit running on a device is to simply pass transpile the backend object and let it grab the properties it needs. transpile returns a new QuantumCircuit object that is compatible with the backend. The following code snippet shows what the simplest usage of the transpiler looks like:

fromqiskitimporttranspiletranspiled_circuit=transpile(circuit,backend)

For example, here we create a simple QuantumCircuit with one qubit, a YGate and two CXGates:

fromqiskitimportQuantumCircuitqc=QuantumCircuit(3)qc.y(0)fortinrange(2):qc.cx(0,t+1)qc.draw()

Figure 4-1 shows the output of qc.draw().

Figure 4-1. Simple circuit with a Y gate and two CX gates

In the next code snippet, we decide we want to run qc on the mock backend FakeSantiago (a mock backend contains the properties and noise models of a real system and uses the AerSimulator to simulate that system). We can see in the output (shown after the code) that FakeSantiago doesn’t understand the YGate operation:

fromqiskit.test.mockimportFakeSantiagosantiago=FakeSantiago()santiago.configuration().basis_gates['id','rz','sx','x','cx','reset']

So qc will need transpiling before running. In the next code snippet, we’ll see what the transpiler does when we give it qc and tell it to transpile for santiago:

t_qc=transpile(qc,santiago)t_qc.draw()

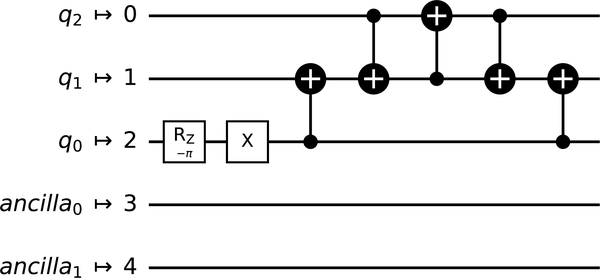

Figure 4-2 shows the output of t_qc.draw().

Figure 4-2. Result of transpiling a simple circuit

We can see in Figure 4-2 that the transpiler has done the following:

-

Mapped (virtual) qubits 0, 1, and 2 in

qcto (physical) qubits 2, 1, and 0 int_qc, respectively -

Added three more

CXGates to swap (physical) qubits 0 and 1 -

Replaced our

YGatewith anRZGateand anXGate -

Added two extra qubits (as

santiagohas five qubits)

Most of this seems pretty reasonable, except the addition of all those CXGates. CXGates are generally quite expensive operations, so we want to avoid them as much as possible. So why has the transpiler done this? In some quantum systems, including santiago, not all qubits can communicate directly with one other.

We can check which qubits can talk to one other through that system’s coupling map (run backend.configuration().coupling_map to get this). A quick look at santiago’s coupling map shows us that physical qubit 2 can’t talk to physical qubit 0, so we need to add a swap somewhere.

Here is the output of santiago.configuration().coupling_map:

[[0,1],[1,0],[1,2],[2,1],[2,3],[3,2],[3,4],[4,3]]

When calling transpile, if we set initial_layout=[1,0,2], we can change the way qc maps to the backend and avoid unnecessary swaps. Here, the index of each element in the list represents the virtual qubit (in qc), and the value at that index represents the physical qubit. This improved layout overrides the transpiler’s guess, and it doesn’t need to insert any extra CXGates. The following code snippet shows this:

t_qc=transpile(qc,santiago,initial_layout=[1,0,2])t_qc.draw()

Figure 4-3 shows the output of t_qc.draw() in the preceding code snippet.

As santiago has only five qubits, it was relatively easy to spot a good layout for this circuit on this device. For larger circuit/device combinations, we will want to do this algorithmically. One option is to set optimization_level=2 to ask the transpiler to use a smarter (but more expensive) algorithm to select a better layout.

Figure 4-3. Result of transpiling a simple circuit with a smarter initial layout

The transpile function accepts four possible settings for

optimization_level:

optimization_level=0-

The transpiler simply does the absolute minimum necessary to get the circuit running on the backend. The initial layout keeps the indices of physical and virtual qubits the same, adds any swaps needed, and converts all gates to basis gates.

optimization_level=1-

This is the default value. The transpiler makes smarter decisions. For example, if we have fewer virtual than physical qubits, the transpiler chooses the most well-connected subset of physical qubits and maps the virtual qubits to these. The transpiler also combines/removes sequences of gates where possible (e.g., two

CXGates that cancel each other out). optimization_level=2-

The transpiler will search for an initial layout that doesn’t need any swaps to execute the circuit or, failing this, go for the most well-connected subset of qubits. Like level 1, the transpiler also tries to collapse and cancel out gates where possible.

optimization_level=3-

This is the highest value we can set. The transpiler will use smarter algorithms to cancel out gates in addition to the measures taken with

optimization_level=2.

Transpiler Passes

Depending on your use case, the transpiler is often invisible. Functions like execute call it automatically, and thanks to the transpiler, we can usually ignore the specific device we’re working on when creating circuits.

Despite this low profile, the transpiler can have a huge effect on the performance of a circuit. In this section, we’ll look at the decisions the transpiler makes and see how to change its behavior when we need to.

The PassManager

We build a transpilation routine from a bunch of smaller “passes.” Each pass is a program that performs a small task (e.g., deciding the initial layout or inserting swap gates), and we use a PassManager object to organize our sequence of passes.

In this section, we’ll show a simple example using the BasicSwap pass.

First, we need a quantum circuit to transpile. The following code snippet creates a simple circuit we’ll use as an example:

fromqiskitimportQuantumCircuitqc=QuantumCircuit(3)qc.h(0)qc.cx(0,2)qc.cx(2,1)qc.draw()

Figure 4-4 shows the output of qc.draw().

Figure 4-4. Simple circuit containing two CX gates

Next, we need to import and construct the PassManager and the passes we want to use. The BasicSwap constructor asks for the coupling map of the device we want to run our circuit on. In the following code snippet, we’ll pretend we want to run this on a device in which qubit 0 can’t interact with qubit 2 (but qubit 1 can interact with both). The PassManager constructor asks for the passes we want to apply to our circuit, which in this case is just the basic_swap pass we created in the preceding line:

fromqiskit.transpilerimportPassManager,CouplingMapfromqiskit.transpiler.passesimportBasicSwapcoupling_map=CouplingMap([[0,1],[1,2]])basic_swap_pass=BasicSwap(coupling_map)pm=PassManager(basic_swap_pass)

Now that we’ve created our transpilation procedure, we can apply it to the circuit using the following code snippet:

routed_qc=pm.run(qc)routed_qc.draw()

Figure 4-5 shows the output of routed_qc.draw().

Figure 4-5. Simple circuit containing two CX gates and two swaps needed to execute on hardware

In Figure 4-5, we can see the basic_swap pass has added in two swap gates to carry out the CXGates, though note that it hasn’t returned the qubits to their original order.

Compiling/Translating Passes

To get a circuit running on a device, we need to convert all the operations in our circuit to instructions the device supports. This can involve breaking high-level gates into lower-level gates (a form of compiling) or translating one set of low-level gates to another. Figure 4-6 shows how the transpiler might break a multicontrolled-X gate down to smaller gates.

Figure 4-6. Example of a multicontrolled-X gate decomposed into H, phase, and CX gates

At the time of writing, Qiskit has two ways of working out how to break a gate down into smaller gates. The first is through the gate’s definition attribute. If set, this attribute contains a QuantumCircuit equal to that gate. The Decompose and Unroller passes both use this definition to expand circuits. The Decompose pass expands the circuit by only one level; i.e., it won’t then try to decompose the definitions we replaced each gate with. The .decompose() method of the QuantumCircuit class uses the Decompose pass. The Unroller pass is similar, but it will continue decomposing the definitions of each gate recursively until the circuit contains only the basis gates we specify when we construct it.

The second way of breaking down gates is by consulting an EquivalenceLibrary. This library can store many definition circuits for each instruction, allowing passes to choose how to decompose each circuit. This has the advantage of not being tied to one specific set of basis gates. The BasisTranslator constructor needs an EquivalenceLibrary and a list of gate name labels. If the circuit contains gates not in the equivalence library, then we have no option but to use those gates’ built-in definitions. The UnrollCustomDefinitions pass looks at the EquivalenceLibrary, and if each gate does not have an entry in the library, it unrolls that gate using its .definition attribute. In the preset transpiler routines (which we’ll see later in this chapter), we’ll usually see the UnrollCustomDefinitions pass immediately before the BasisTranslator pass.

Routing Passes

Some devices can perform multiqubit gates only between specific subsets of qubits. IBM’s hardware tends to allow only one multiqubit gate (the CXGate) and can perform these gates only between specific pairs of qubits. We call a list of each pair of possible two-qubit interactions a coupling map. We saw an example of this in “The PassManager”. In that example, we overcame this limitation by using swap gates to move qubits around in the coupling map. Figure 4-7 shows an example of a coupling map.

Figure 4-7. Drawing of a coupling map: [[0, 1], [1, 2], [2, 3], [3, 1]]

Qiskit has a few algorithms to add these swap gates. Table 4-1 lists each of the available swapping passes, with a brief description of the pass.

Optimization Passes

The transpiler acts partly as a compiler, and like most compilers, it also includes some optimization passes. The biggest problem in modern quantum computers is noise, and the focus of these optimization passes is to reduce the noise in the output circuit as much as possible. Most of these optimization passes try to reduce noise and running time by minimizing gate count.

The simplest optimizations look for sequences of gates that have no effect, so we can safely remove them. For example, two CXGates back-to-back would have no effect on the unitary matrix of the circuit, so the CXCancellation pass removes them. Similarly, the RemoveDiagonalGatesBeforeMeasure pass does as it advertises and removes any gates with diagonal unitaries immediately before a measurement (as they won’t change measurements in the computational basis). The OptimizeSwapBeforeMeasure pass removes SWAP gates immediately before a measurement and remaps the measurements to the classical register to preserve the output bit string.

Qiskit also has smarter optimization passes that attempt to replace groups of gates with smaller or more efficient groups of gates. For example, we can easily collect sequences of single-qubit gates and replace them with a single UGate, which we can then break back down into an efficient set of basis gates. The Optimize1qGates and Optimize1qGatesDecomposition passes both do this for different sets of initial gates. We can also do the same for two-qubit gates; Collect2qBlocks and ConsolidateBlocks find sequences of two-qubit gates and compile them into one two-qubit unitary matrix. The UnitarySynthesis pass can then break this back down to the basis gates of our choosing.

For example, Figure 4-8 shows two circuits with identical unitaries but different numbers of gates.

Figure 4-8. Example of the same circuit after going through two different transpilation processes

Initial Layout Selection Passes

As with routing, we also need to choose how to initially map our virtual circuit qubits to the physical device qubits. Table 4-2 lists some layout selection algorithms Qiskit offers.

| Name | Explanation |

|---|---|

|

This pass simply maps circuit qubits to physical qubits via their indexes. For example, the circuit qubit with index 3 will map to the device qubit with index 3. |

|

This pass finds the most well-connected group of physical qubits and maps the circuit qubits to this group. |

|

This pass uses information about the device’s noise properties to choose a layout. |

|

This pass uses the SABRE algorithm to find an initial layout requiring as few SWAPs as possible. |

|

This pass converts layout selection to a constraint satisfaction problem (CSP). The pass then uses the |

Preset PassManagers

When we used the high-level transpile function before, we didn’t worry about the individual passes and instead set the optimization_level parameter. This parameter tells the transpiler to use one of four preset pass managers. Qiskit builds these preset pass managers through functions that take configuration settings and return a PassManager object. Now that we understand some passes, we can have a look at what the different transpilation routines are doing.

Following is the code we used to extract the passes used for a simple transpilation routine in case you want to reproduce it:

fromqiskit.transpilerimport(PassManagerConfig,CouplingMap)fromqiskit.transpiler.preset_passmanagersimport\level_0_pass_managerfromqiskit.test.mockimportFakeSantiagosys_conf=FakeSantiago().configuration()pm_conf=PassManagerConfig(basis_gates=sys_conf.basis_gates,coupling_map=CouplingMap(sys_conf.coupling_map))fori,stepinenumerate(level_0_pass_manager(pm_conf).passes()):(f'Step{i}:')fortranspiler_passinstep['passes']:(f'{transpiler_pass.name()}')

We have not covered some of the following passes in this chapter because they are analysis passes that do not affect the circuit or because they are cleanup passes for which we don’t have a choice of algorithm. These passes are unlikely to have an avoidable, negative effect on the performance of our circuits. We have also not covered some pulse-level passes that are out of the scope of this chapter:

Step0:SetLayoutStep1:TrivialLayoutStep2:FullAncillaAllocationEnlargeWithAncillaApplyLayoutStep3:Unroll3qOrMoreStep4:CheckMapStep5:BarrierBeforeFinalMeasurementsStochasticSwapStep6:UnrollCustomDefinitionsBasisTranslatorStep7:TimeUnitConversionStep8:ValidatePulseGatesAlignMeasures

Remember that optimization_level=0 does the bare minimum needed to get the circuit running on the device. Notably, we can see it uses TrivialLayout to choose an initial layout, then expands the circuit to have the same number of qubits as the device. The transpiler then unrolls the circuit to single and two-qubit gates and uses StochasticSwap for routing. Finally, it unrolls everything as far as possible and translates the circuit to the device’s basis gates.

For optimization_level=3, on the other hand, the PassManager contains the following passes:

Step0:Unroll3qOrMoreStep1:RemoveResetInZeroStateOptimizeSwapBeforeMeasureRemoveDiagonalGatesBeforeMeasureStep2:SetLayoutStep3:TrivialLayoutLayout2qDistanceStep4:CSPLayoutStep5:DenseLayoutStep6:FullAncillaAllocationEnlargeWithAncillaApplyLayoutStep7:CheckMapStep8:BarrierBeforeFinalMeasurementsStochasticSwapStep9:UnrollCustomDefinitionsBasisTranslatorStep10:RemoveResetInZeroStateStep11:DepthFixedPointCollect2qBlocksConsolidateBlocksUnitarySynthesisOptimize1qGatesDecompositionCommutativeCancellationUnrollCustomDefinitionsBasisTranslatorStep12:TimeUnitConversionStep13:ValidatePulseGatesAlignMeasures

This PassManager is quite different. After unrolling to single and two-qubit gates, we can already see some optimization passes in Step 1 removing unnecessary gates. The transpiler then tries a few different layout selection approaches. First, it checks if the TrivialLayout is optimal (i.e., if it doesn’t need any SWAPs inserting to execute on the device). If it isn’t, the transpiler then tries to find a layout using CSPLayout. If CSPLayout fails to find a solution, then the transpiler uses the DenseLayout algorithm. Next (Step 6), the transpiler adds extra qubits (if needed) to make the circuits have the same number of qubits as the device. It then uses the StochasticSwap algorithm to make all two-qubit gates possible on the device’s coupling map. With the routing taken care of, the transpiler then translates the circuit to the device’s basis gates before attempting some final optimizations in Step 11.

Looking at the optimization_level=3 passes, we can see that the transpiler is a very sophisticated program that can have a big influence on the behavior of your circuits. Fortunately, you now understand the problems the transpiler must solve and some of the algorithms it uses to solve them.

Get Qiskit Pocket Guide now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.