Analytics are key to a strong startup business model

Learn how to create a business model that includes the right metrics and get an introduction to the Business Model Flipbook planning tool.

Lemonade stand. (source: Pixabay)

Lemonade stand. (source: Pixabay)

How you get and make money drives what metrics you should

care about. In the long term, the riskiest part of a business is often

directly tied to how it makes money.

Many startups can build a product and solve technical issues, some

can attract the right (and occasionally large) audiences, but few make

money. Even giants like Twitter and Facebook have struggled with

extracting money from their throngs of users.

There’s no more iconic symbol of a startup than the lemonade

stand, and with good reason—it’s a simple, entrepreneurial, low-risk way

to learn how businesses operate. And like a lemonade stand, while it

might be reasonable and strategic to delay monetization—giving away

lemonade for a while to build a clientele—you have to be planning your

business model early on.

If we asked you to describe the business model of a lemonade

stand, you’d probably say that it’s about selling lemonade for more than

it costs to make it. Pressed for more detail, you might say that costs

include:

-

Variable costs of materials (lemons, sugar, cups,

water) -

One-time costs of marketing (stand, signage, cooler, bribing a

younger sibling to stand in the street) -

Hourly costs of staffing (which, let’s face it, are pretty

negligible when you’re a kid)

You might also say that revenue is a function of the price you

charge, and the number of cups sold.

Now let’s suppose that you’re asked to identify the risky

parts of the business. They include the variability of citrus futures,

the weather, the foot traffic in your neighborhood, and so on.

One thing we’ve noticed about almost all successful founders we’ve

met is their ability to work at both a very detailed, and a very

abstracted, level within their business. They can worry about the layout

of a page or the wording of an email subject one day, and consider the

impact of one-time versus monthly recurring sales the next. That’s

partly because they’re not only trying to run a business, they’re also

trying to discover the best business model.

To decide which metrics you should track, you need to be able to

describe your business model in no more complex a manner than a lemonade

stand’s. You need to step back, ignore all the details, and just think

about the really big components.

When you reduce things to their basic building blocks in this way,

you come up with only a few fundamental business models on the Web.

Interestingly, all of them share some common themes. First, their aim is

to grow (in fact, Paul Graham says that a focus on growth is the one

defining attribute of a startup).1 And second, that growth is achieved by one of Eric Ries’s

fundamental Engines of Growth: an increase in stickiness, virality, or

revenue.

Each business model needs to maximize the thrust from these three

engines in order to flourish. Sergio Zyman, Coca-Cola’s CMO, said

marketing is about selling more stuff to more people more

often for more money more efficiently.2

Business growth comes from improving one of these five

“knobs”:

-

More stuff means adding

products or services, preferably those you know your customers want

so you don’t waste time building things they won’t use or buy. For

intrapreneurs, this means applying Lean methods to new product

development, rather than starting an entirely new company. -

More people means adding

users, ideally through virality or word of mouth, but also through

paid advertising. The best way to add users is when it’s an integral

part of product use—such as Dropbox, Skype, or a project management

tool that invites outside users outsiders—since this happens automatically and implies an

endorsement from the inviting user. -

More often means stickiness

(so people come back), reduced churn (so they don’t leave), and

repeated use (so they use it more frequently). Early on, stickiness

tends to be a key knob on which to focus, because until your core

early adopters find your product superb, it’s unlikely you can

achieve good viral marketing. -

More money means upselling

and maximizing the price users will pay, or the revenue from ad

clicks, or the amount of content they create, or the number of

in-game purchases they make. -

More efficiently means

reducing the cost of delivering and supporting your service, but

also lowering the cost of customer acquisition by doing less paid

advertising and more word of mouth.

About Those People

Business models are about getting people to do what you want in

return for something. But not all people are

equal. The plain truth is that not every user is good for

you.

-

Some are good—but only in the long term. Evernote’s freemium

model works partly because users eventually sign up for paying

accounts, but it can take them two years to do so. -

Some provide, at best, free marketing, and while they may

never become paying users, they may amplify your message or invite

someone who will pay. -

Some are downright bad—they distract you, consume resources,

spam your site, or muddy your analytics.

When you get a wave of visibility, few of the resulting visitors

will actually engage with your product. Many are just driving by. As

Vinicius Vacanti, co-founder and CEO of Yipit, recalls in a blog post

inspired by his company’s 2010 launch:3

Was that our big launch? Why didn’t more people sign up? Why

didn’t people complete the sign-up flow? Why weren’t people coming

back? Now that people covered our startup, how are we supposed to

get more press? Why aren’t our users pushing their actions to

Facebook and Twitter? We got some users to invite their friends but

why aren’t their friends accepting the invite?

The key here is analytics. You need to segment real,

valuable users from drive-by, curious, or detrimental ones. Then you

need to make changes that maximize the real users and weed out the bad

ones. That may be as blunt as demanding a credit card up front—a sure

way to reject curious users who don’t have any intention of committing

or paying. Or it may be a subtler approach, such as not trying to

reactivate disengaged users once they’ve been gone for a while.

If you’re a developer of a game that users play once, or an

e-commerce site stocking rarely purchased items, that’s fine—just get

your money up front. If you’re a SaaS provider with low incremental

costs for additional users, freemium may work, as long as you clearly

separate engaged from casual users. If you expect buyers to purchase

from you often, you need to make them feel loved. You get the

picture.

Segmenting real users from casual ones also depends on how much

effort your users have to put into using the application. Some

products collect information passively: Fitbit logs walking steps;

Siri notices when you’ve arrived somewhere; Writethatname analyzes

your inbox for new contacts. Users don’t have to do much, so it can be

hard to tell if they’ve “checked out.” It’s easier to find disengaged

users if they have to actively use the product.

Consider the aforementioned Fitbit, a tiny life-logging device

that measures steps, from which it calculates calories burned, miles

walked, stairs climbed, and overall activity.

Fitbit users can simply record their steps with a device in

their pocket, they can use it to sync data to the company’s hosted

application, they can visit the portal to see their statistics and

share them with friends, they can manually enter sleep and food data

to augment what’s collected passively, and they can buy the premium

Fitbit offering to help them reach their health goals.

Each of these use models represents a different tier of

engagement, and Fitbit could segment users across these five segments.

And it should: it’s perfectly acceptable for a Fitbit user to only use

the clip-on device to record the number of steps taken per day,

without ever uploading that information, but as a result the company

won’t be able to monetize that user beyond the initial purchase

(through on-site ads, premium subscriptions, or selling aggregate user

data, for example). The value of that user is significantly lower.

Predicting revenues accurately relies on an understanding of how its

different user segments employ the product.

As a startup, you have a wide range of payment and incentive

models from which to choose: freemium, free trial, pay up-front,

discount, ad-funded, and so on. Your choice needs to match the kind of

segmentation you’re doing, the time it takes for a user to become a

paying customer, how easy it is to use your service, and how costly an additional

drive-by user is to the business.

Not all customers are good. Don’t fall victim to customer

counting. Instead, optimize for good customers

and segment your activities based on the kinds of customer those

activities attract.

The Business Model Flipbook

A product is more than the thing you buy. It’s the mix of

service, branding, fame, street cred, support, packaging, and myriad

other factors you pay for. When you purchase an iPhone, you’re also

getting a tiny piece of Steve Jobs’s persona.

In the same way, a business model is a combination of things.

It’s what you sell, how you deliver it, how you acquire customers, and

how you make money from them.

Many people blur these dimensions of a business model. We’re

guilty of it, too. Freemium isn’t a business model—it’s a marketing

tactic. SaaS isn’t a business model—it’s a way of delivering software.

The ads on a media site aren’t a business model—they’re a way of

collecting revenue.

Later in the book we’re going to outline six sample businesses.

But before we do that, we want to talk about how we came up with them.

Think of one of the flipbooks you had as a kid—the kind where you

could combine different body parts on each page to make different

characters.

You can build business models this way, but instead of heads,

torsos, and feet, you have several aspects of a business: the

acquisition channel, selling tactic, revenue source, product type, and

delivery model.

-

The acquisition channel

is how people find out about you. -

The selling tactic is how

you convince visitors to become users or users to become

customers. Generally, you either ask for money or you provide some

kind of scarcity or exclusivity—such as a time limit, a capacity

limit, the removal of ads, additional functionality, or the desire

to keep things to themselves—to convince them to act. -

The revenue source is

simply how you make money. Money can come from your customers

directly (through a payment) or indirectly (through advertising,

referrals, analysis of their behavior, content creation, and so

on). It can include transactions, subscriptions, consumption-based

billing charges, ad revenue, resale of data, donations, and much

more. -

The product type is what

value your business offers in return for the revenue. -

The delivery

model is how you get your product to the

customer.

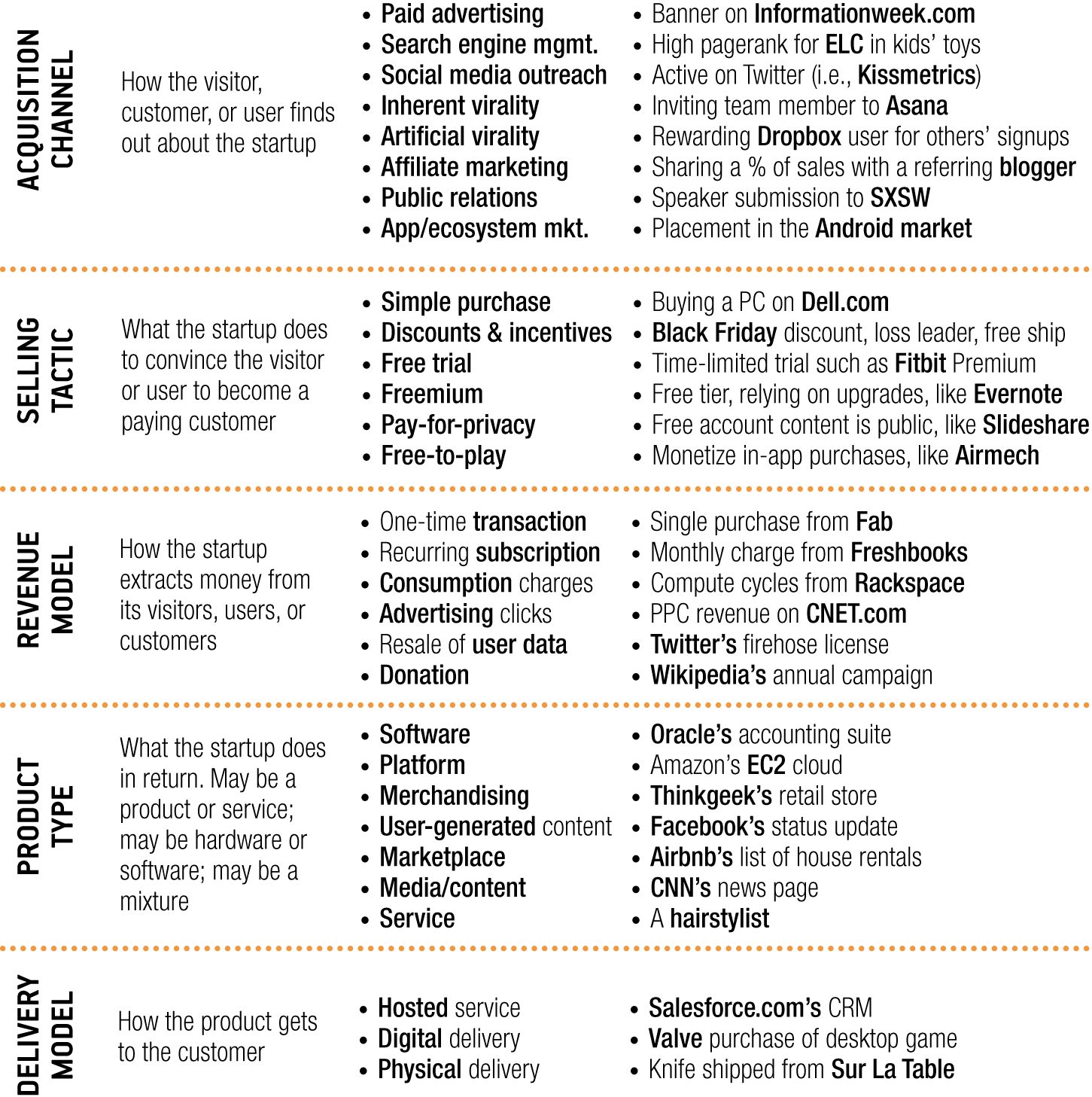

Figure 1-1

shows these five aspects, with a variety of models and examples for

each one. Remember that this is only a set of examples—most businesses

will rely on several acquisition channels, or experiment with

different revenue models, or try various sales tactics.

words

Lots to Choose From

There is an abundance of “pages” you can put into the

flipbook. The team at Startup Compass, a startup dedicated to

helping companies make better business decisions with data,

identifies 12 revenue models: advertising, consulting, data, lead

generation, licensing fee, listing fee, ownership/hardware, rental,

sponsorship, subscription, transaction fee, and virtual goods.

Venture capitalist Fred Wilson has a document listing a vast number

of web and mobile revenue models, many of which are

variants on six basic ones we’ll list later in the book.4

Startup Compass also suggests some “fundamental” financial

models that combine several pages from the flipbook: search, gaming,

social network, new media, marketplace, video, commerce, rental,

subscription, audio, lead generation, hardware, and payments.

You can use these “pages” to create a back-of-the-napkin

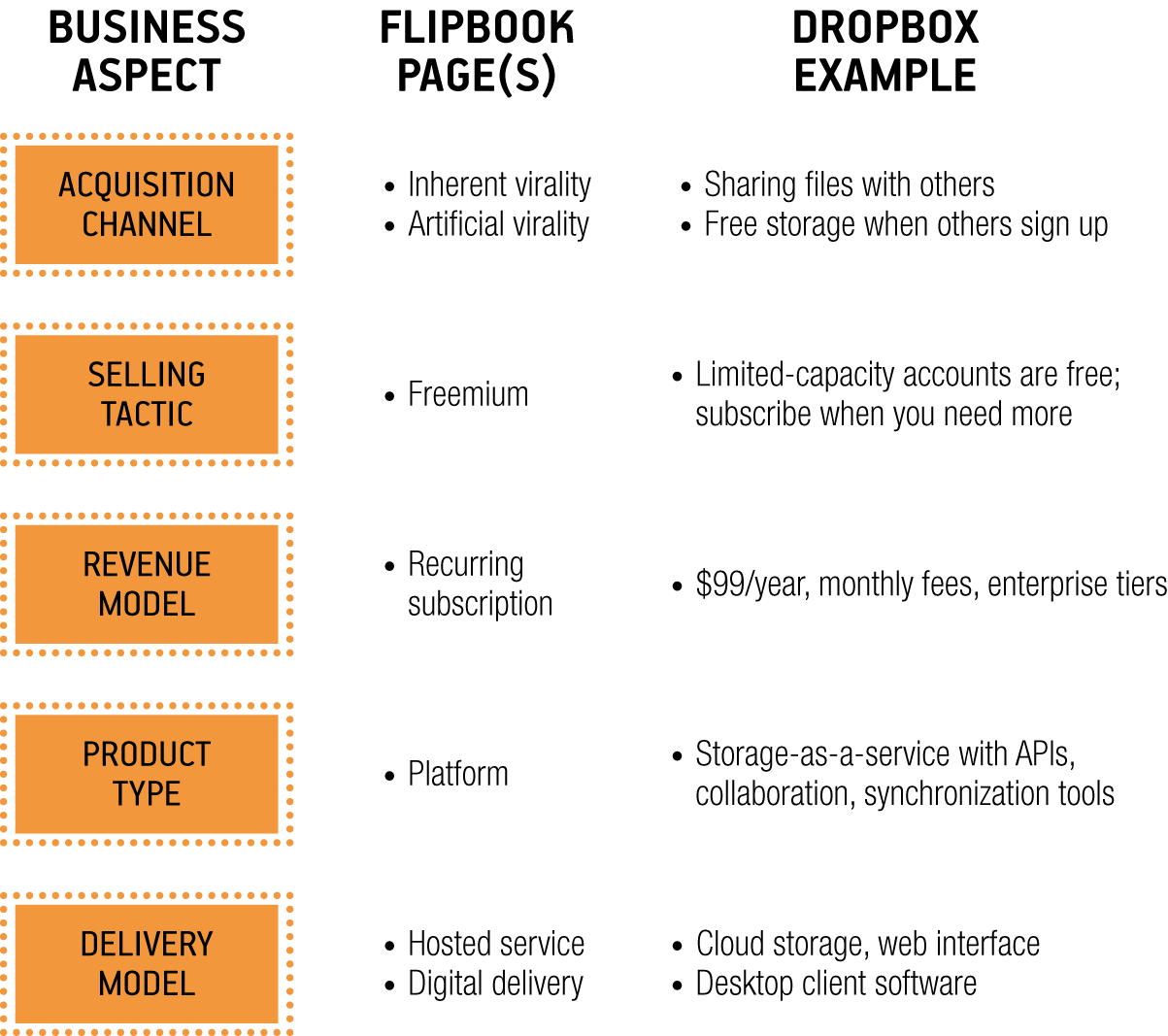

business model. For example, Figure 1-2 shows a sample

business model flipbook for Dropbox.

There’s another advantage of stating business models in a

flipbook structure like this: it encourages lateral thinking. Each

turn of a “page” is a pivot: what would it mean to offer Dropbox as

a physical delivery? Or to charge up front for it? Or to rely on

paid advertising?

Six Business Models

In the coming chapters, we’re going to look at six business

models. Each model is a blend of these aspects, and we’ve tried to mix

them up enough to give you a taste of some common examples. But just

like a kid’s flipbook, there’s a huge variety: from the aforementioned

list, there are over 6,000 permutations, and our list of aspects isn’t

by any means exhaustive.

As if that weren’t confusing enough, you can employ

several at once: Amazon is a transactional, physical-delivery, SEM

(search engine marketing), simple-purchase retailer, but it’s also

running sub-businesses such as user-generated content in the form of

product reviews. So unlike those relatively simple children’s books,

your business can quite easily be a many-headed monster.

In the face of this complexity, we’ve decided to keep our six

business models simple. We’ll talk about several aspects of those

businesses, and the metrics that matter most to companies of each

sort. Think of it as opening the business model flipbook to a

particular “page”—one in which you see elements of your own

business.

-

If you’re running an e-commerce business where you sell

things to customers, turn to not available. -

If you’re delivering SaaS to users, turn to not available.

-

If you’re building a mobile application and using in-app

purchases to generate revenue, head to not available. -

If you’re creating content and making money from

advertising, you’ll find details on media sites in not available. -

If your primary focus is getting your users to generate

content on your platform the way Twitter, Facebook, or reddit do,

turn to not available. -

If you’re building a two-sided marketplace where buyers and

sellers can come together, check out not available.

Most businesses fall into one of these categories. Some won’t,

but they have close parallels in the real world. A restaurant is

transactional, like e-commerce; an accounting business offers a

recurring service, like a SaaS company, and so on. Hopefully, you’ll

find a model that’s close enough for you to learn important lessons

about analytics and apply them to your business, as we review the

stages of growth in not available and beyond.

Pick Your Business Model

In the following chapters we go through six sample business

models. Find yours and write it down, then list all the metrics we

define in that business model and see how well that aligns with what

you’re tracking. For the metrics that you’re tracking, put down the

values as they stand today, if you haven’t already. If your business

overlaps on a couple of models (which isn’t uncommon), then grab

metrics from each of those models and include them in this

exercise.