Chapter 1. Lost and Found

At the seashore, between the land of atoms and the sea of bits, we are now facing the challenge of reconciling our dual citizenship in the physical and digital worlds.

—Hiroshi Ishii

MIT Media Lab

I’m sitting on a beach in Newport, Rhode Island. Seagulls and sandpipers hunt near the water’s edge. The Atlantic ocean sparkles in the early morning sun. To my right, the Cliff Walk winds its way between the rugged New England shoreline and the manicured gardens of the Newport mansions, opulent “summer cottages” built with industrial age fortunes made in steamships, railroads, and foreign trade.

I’m sitting on a beach in Newport, but I’m not entirely there. My attention is focused on a device that rests in the palm of my hand. It’s a Treo 600 smartphone. I’m using it to write this sentence, right here, right now. As a 6.2 ounce computer sporting a 144 megahertz RISC processor, 32 megabytes of RAM, a color display, and a full QWERTY keyboard, this is one impressive micro-machine. But that’s not what floats my boat. What I love about this device is its ability to reach out beyond the here and now.

By integrating a mobile phone and Palm Powered organizer with wireless email, text messaging, and web browsing, the Treo connects me with global communication and information networks. I can make a phone call, send email, check the weather, buy a book, learn about Newport, and find a restaurant for lunch. The whole world is accessible and addressable through this 21st Century looking glass in the palm of my hands.

But make no mistake, this device is a two-way mirror. Not only can people reach out and touch me with a phone call, an email, or a text message. Equipped with the right technology, someone could pinpoint my location within a few hundred feet. Like most new smartphones, my Treo includes an embedded Global Positioning System chip designed to support E911 emergency location services. In other words, I’m findable.

Here’s where things get interesting. We’re at an inflection point in the evolution of findability. We’re creating all sorts of new interfaces and devices to access information, and we’re simultaneously importing tremendous volumes of information about people, places, products, and possessions into our ubiquitous digital networks.

Consider the following examples:

There’s a company called Ambient Devices that embeds information representation into everyday objects: lights, pens, watches, walls, and wearables. You can buy a wireless Ambient Orb that shifts colors to show changes in the weather, stock market, and traffic patterns based on user preferences you set on a web site.

From the highways of Seattle and Los Angeles to the city streets of Tokyo and Berlin, embedded wireless sensors and real-time data services for mobile devices are enabling motorists to learn about and route around traffic jams and accidents.

Pioneers in “convergent architecture” have built the Swisshouse, a new type of consulate in Cambridge, Massachussetts that connects a geographically dispersed scientific community. It may not be long before persistent audio-video linkages and “web on the wall” come to a building near you.

Delicious Library’s social software turns an iMac and FireWire digital video camera into a multimedia cataloging system. Simply scan the barcode on any book, movie, music, or video game, and the item’s cover appears on your digital shelves along with tons of information from the Web. This sexy, location-aware, peer-to-peer, personal lending library lets you share your collection with friends and neighbors.

You can buy a watch from Wherify Wireless with an integrated global positioning system (GPS) that locks onto your kid’s wrist, so you can pinpoint his location at any time. A nifty “breadcrumb” feature shows where your child has wandered over the course of several hours. Similar devices are available in amusement parks such as Denmark’s Legoland, so parents can quickly find their lost children.

Manufacturers such as Procter & Gamble have already begun inserting radio-frequency identification tags (RFIDs) into products so they can reduce theft and restock shelves more efficiently. These tags continue to function long after products leave the store and enter the home or business.

At the Baja Beach Club in Barcelona, patrons can buy drinks and open doors with a wave of their hand, compliments of a syringe-injected, RFID microchip implant. The system knows who you are, where you are, and your exact credit balance. Getting “chipped” is considered a luxury service, available for VIP members only.

The size and price of processors, sensors, radio frequency identification tags, and related technologies are approaching a tipping point. Today’s expensive prototypes are tomorrow’s dirt cheap products. Imagine the ability to track the location of anyone or anything from anywhere at anytime. Simply affix a tiny sticker to your TV’s remote control or to the bottom of your spouse’s shoe, and then fire up your Treo’s web browser.

We’re stepping through the looking glass into an information-rich world with new possibilities and problems. We will find delight in groovy gadgets and location-based services. Individuals and institutions will achieve greater flexibility and productivity. And yet, we will struggle to balance privacy, freedom, convenience, and safety.

And amidst all this novelty, our vaunted ability to “learn how to learn” will be put to the test. How will we make informed decisions? How will we know enough to ask the right questions? Nine billion web pages. Six billion people. Who do you ask? Who do you trust? How do you find the best product, the right person, the data that makes a difference?

The answers are hidden in the strange connections between wayfinding, social software, information retrieval, decision trees, self-organization, evolutionary psychology, librarianship, and authority. As William Gibson, the science-fiction author who coined the term cyberspace, once noted, “The future exists today. It’s just unevenly distributed.”

Where the Internet meets ubiquitous computing, the histories of navigation, communication, commerce, and information seeking converge. We increasingly use mobile devices to find our way, to find products, to find answers, and to find ourselves. As we map the emerging shoreline that connects the land of atoms and the sea of bits, findability serves as a useful lens for seeing where we’ve been and what lies ahead.

Definition

At this point, you may be wondering: what exactly is findability? This section is for you.

The quality of being locatable or navigable.

The degree to which a particular object is easy to discover or locate.

The degree to which a system or environment supports navigation and retrieval.

Findability is a quality that can be measured at both the object and system levels. We can study the attributes of an individual object that make it more or less findable. The title of a document. The color of a life jacket. The presence of an embedded RFID tag. And we can evaluate how well an overall system supports people’s ability to find their way and find what they need. Can patients navigate a hospital? Can users navigate a web site?

Of course, the successes of findable objects and their systems are often closely linked. An orange life jacket fails to grab attention in an orange ocean, but a statistically improbable phrase jumps right out in a sea of books. Findability requires definition , distinction, difference. In physical environments, size, shape, color, and location set objects apart. In the digital realm, we rely heavily on words. Words as labels. Words as links. Keywords.

The humble keyword has become surprisingly important in recent years. As a vital ingredient in the online search process, keywords have become part of our everyday experience. We feed keywords into Google, Yahoo!, MSN, eBay, and Amazon. We search for news, products, people, used furniture, and music. And words are the key to our success.

The power of the keyword search has combined with the richness of the World Wide Web to foment a revolution in the way we do business. This revolution is not simply about moving the shopping experience online. It’s about empowering individuals with information and choice. Never before has the consumer had so much access to product information before the point of purchase. Never before have we had so many products to choose from. Power has shifted and continues to shift toward the consumer.

As the pendulum swings from push to pull, the effectiveness of advertising diminishes relative to the importance of product design and quality and price. No longer forced to trust the promotional spin of television advertisements and predatory salespeople, we now have the ability to find the best products and the best deals. We can make informed decisions, thanks to the simple keyword and our sophisticated engines of findability.

For when you examine the tools and systems available for finding and evaluating products, keyword search is only the beginning. Consider the richness of Amazon, where we can compare and contrast myriad products in amazing detail. The hunt starts with a keyword search or perhaps the choice of category and subcategory.

Let’s say we’re looking for a digital camera. We choose Electronics, then Camera and Photo, then Digital Cameras. Now the selection really begins. We can browse by brand or filter by megapixel range. We can focus on the bestsellers or the lowest prices. For any given camera, we can view descriptions and specifications from the manufacturer, and weigh their claims against the color commentary of customer reviews.

This camera is awesome! That camera sucks! There’s no tripod mount. You can’t recharge the battery overseas. This one’s too small for people with big hands. Try this one instead. I dropped mine in a pond but it still works perfectly fine.

These customer reviews are funny, insightful, and valuable, yet they also force us to play a more active role in evaluating our sources of information. Who do we trust? Amazon? The manufacturer? Some random customer? We need to validate claims by cross-reference, so we check out Epinions, CNET, and Consumer Reports. And if possible, we ask a friend. All of these sources and our own judgments about their trustworthiness and credibility inform the process of finding the right product.

The credibility and authority of sources become even more important when we step into the arena of health information. In an age of skyrocketing health care costs and doctors with little time to spare, we are taking our questions online. In the United States, 80% of adult Internet users, or almost half of Americans over the age of 18 (about 95 million individuals) have researched health and medical topics on the Internet. We learn about specific diseases. We educate ourselves about medical procedures. We search for nutritional supplements. And we seek alternative treatments and medicines for ourselves and for our loved ones. In the process, our literacy is put to the test. Can we find what we seek? Can we evaluate what we do find? Are our decisions getting better or worse?

I can tell you from personal experience that Google does not perform well when it comes to health. Recently, our youngest daughter, Claudia, was diagnosed with a severe peanut allergy. Suddenly interested in a topic I had never cared about before, I turned to the Web for answers. Google sent me to specialized sites such as http://peanutallergy.com, a shallow and grossly commercial web site pushing favored brands of nut free chocolate and soynut butter. Yahoo! and MSN didn’t perform any better. I did eventually find what I needed, but only by drawing on my advanced searching skills and familiarity with authoritative sources like the National Institutes of Health and the Centers for Disease Control. If I weren’t a librarian who lives on the Web, I would have failed to find the right answers.

Sometimes the health information we find online validates our doctor’s diagnosis or advice. Sometimes it sends us for a second opinion. And sometimes it simply makes us feel better informed and more confident. Consider the following excerpt from an email message sent to the National Cancer Institute:

Last evening I learned my 72 yr. old mother has lung cancer. Still in a state of shock she was not able to provide me with much information. She lives four hours from me and I am unable to be with her at this moment due to work obligations. So until I can be with her I am taking the time to learn as much as possible on the subject of lung cancer. So I would like to thank the person or persons for this very informative web site. This web site has given me the information on how I as a daughter can help my mother and also teach my family what to expect in the next coming months. Thank you!

In this message of grief and gratitude, we can find hope and inspiration. Hope in the reality of progress. The sender couldn’t have found what she needed only a few years ago. Though we already take it for granted, the Internet is still the fastest growing new medium of all time. And inspiration in understanding that the work we do to connect people with content and services and one another truly makes a difference. Designers, developers, writers, and others who labor behind the screens to shape the user experience rarely get to see the personal impact of their work. We maintain empathy for the user as a matter of faith. Messages from and contact with our users help us to renew that faith.

Of course, the user experience is increasingly out of control, as wireless devices inject new interfaces and affordances into an already complex network ecology. How do we design for mobility? How do we create good experiences when we can’t predict context of use? Will our users be in the office or in the bathtub? What’s their bandwidth and screen size? The variables will only multiply as ubicomp transforms the Web into both interface and infrastructure for an ambient Internet of objects we can barely imagine.

Surrounding; encircling: e.g., ambient sound.

Completely enveloping.

Ambient findability describes a fast emerging world where we can find anyone or anything from anywhere at anytime. We’re not there yet, but we’re headed in the right direction. Information is in the air, literally. And it changes our minds, physically. Most importantly, findability invests freedom in the individual. As the Web challenges mass media with a media of the masses, we will enjoy an unprecented ability to select our sources and choose our news. In my opinion, findability is going ambient, just in time.

Information Literacy

The average child in the United States watches four hours of television every day. These kids are exposed to 20,000 commercials annually. They see 8,000 onscreen murders by the time they finish grade school. Is this a good thing? As a society, we send mixed signals. On the one hand, we condemn the evils of television. Authorities such as the American Academy of Pediatrics warn that TV viewing may lead to more aggressive behavior, less physical activity, and risky sexual behavior. Newspaper headlines blame television for our epidemics of violence, obesity, and illiteracy. And yet, we let our children watch it. Perhaps we question the authorities and doubt the headlines. Perhaps we lack the time or energy to intervene. Or perhaps we trust that things will be okay because all the other kids are watching too. Perhaps.

Whenever I hear about the dominance of television and the decline of literacy, I experience a disconnect. While I do fear for the health of this media-saturated generation, I don’t worry about their ability to read and write. Our culture does not reward illiteracy. On the contrary, it’s almost impossible to function in modern society without mastering the skills of written communication. If you can’t fill out a form, you’re in trouble. The literacy rate in the United States is 97%. It’s 99% throughout most of Europe. Basic literacy is not in danger. However, it’s also not enough.

Our children are inheriting a media landscape that’s breathtaking and bewildering. Books, magazines, newspapers, billboards, telephones, televisions, videotapes, video games, email messages, text messages, instant messages, web sites, weblogs, wikis, and the list goes on. It’s exciting to have all these communication tools and information sources at our disposal, but the complexity of the environment demands new kinds of literacy. Gone are the days when we can look up the “right answer” in the family encyclopedia. Nowadays there are many answers in many places. We can find them in Microsoft Encarta or in the Wikipedia. We can find them via Google. There is so much to find, but we must first know how to search and who to trust. In the information age, transmedia information literacy is a core life skill.

The American Library Association defines information literacy as “a set of abilities requiring individuals to recognize when information is needed and have the ability to locate, evaluate, and use effectively the needed information.”

Information literacy also is increasingly important in the contemporary environment of rapid technological change and proliferating information resources. Because of the escalating complexity of this environment, individuals are faced with diverse, abundant information choices—in their academic studies, in the workplace, and in their personal lives. Information is available through libraries, community resources, special interest organizations, media, and the Internet—and increasingly, information comes to individuals in unfiltered formats, raising questions about its authenticity, validity, and reliability. In addition, information is available through multiple media, including graphical, aural, and textual, and these pose new challenges for individuals in evaluating and understanding it. The uncertain quality and expanding quantity of information pose large challenges for society. The sheer abundance of information will not in itself create a more informed citizenry without a complementary cluster of abilities necessary to use information effectively.[*]

Information literacy helps individuals succeed. As consumers, fluency with the use of multiple media enables us to find the best products at the best prices more efficiently. Whether you’re buying a book or a car or a house, the Internet can often save you significant time and money. As producers, information literacy helps us find and keep the best jobs. Knowledge workers are paid for their ability to find, filter, analyze, create, and otherwise manage information. Those who lack these skills become lost on the wrong side of the digital divide. As a society, we must continue to invest in the education of our children, and we must work harder to develop information literacy among our citizens.

Business Value

Let’s say you’re unmoved by the idealistic call for greater literacy. Our children may be our future, but you’ve got budget problems and business challenges today. Why should you care about findability? Why should you learn more about social software, semantic webs, and search engine optimization? What can findability do for you?

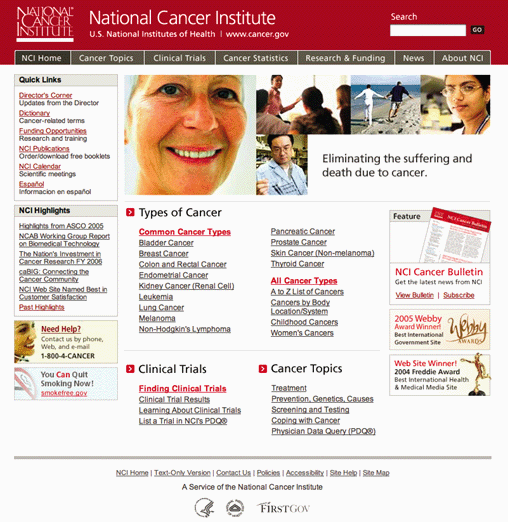

We begin our quest for business value in the unlikely domain of a federal government agency. Yes, we’re back at the National Cancer Institute where I recently had the good fortune to collaborate with a great team of people on redesigning the http://cancer.gov web site. I was brought in to lead the information architecture strategy. My goals were to improve navigation and usability, and reduce the number of clicks required to access key content.

The in-house team at NCI had done a great job analyzing patterns of use. They understood who visits, why they visit, and where they spend their time. They knew the majority of site visitors are people recently diagnosed with cancer (and their friends and family members). And their data showed the home pages for specific types of cancer were among the most visited. So, among other goals, they wanted to reduce the time and number of clicks it took to navigate from the NCI home page to cancer type home pages.

Now, being a findability fanatic, I couldn’t help inquiring about how people find the web site in the first place. My clients didn’t have much data on this topic, but they told me not to worry about this type of findability. Our site comes up as the first or second hit for searches on “cancer” on Google and Yahoo! they told me, so we’re all set.

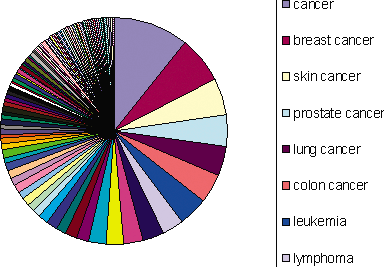

But I did worry, and I did a bit of digging. I used Overture’s Search Term Suggestion Tool to get a sense of the types of cancer-related searches being performed on public search engines. Sure enough, the generic query on “cancer” was the single most popular search (i.e., 180,000 queries per month). But queries on specific types of cancer were also very common (e.g., 132,000 on “breast cancer” per month). In fact, when you totaled the searches on specific types of cancer, they outnumbered the generic searches by a 5:1 ratio, as Figure 1-1 shows. This makes sense. If you’re diagnosed with breast cancer, you’re very likely to search on “breast cancer” rather than explore the more general category of cancer.

Yet when I tried Google and Yahoo! searches on “breast cancer” and “prostate cancer” and “mesothelioma,” http://cancer.gov didn’t come up in the first screen of results. It was drowned out by a multitude of more specialized, more commercial, less detailed, less trustworthy web sites. For users with these specific queries, the NCI site, shown in Figure 1-2, was essentially unfindable. In my opinion, this was a major problem. In fact, I told my clients that if they had to choose between having me redesign the information architecture and having a search engine optimization firm improve cancer type home page visibility for the most important and common cancer-related keyword searches, I’d recommend the latter.

Fortunately, my clients weren’t forced to choose. In fact, we worked together on a holistic findability strategy to make it easier for users to find the site, to find the site’s content, and to find their way around the site. And, in the year since this http://cancer.gov redesign, the National Cancer Institute has won a Webby Award and a Freddie Award and has climbed to the very top of the American Customer Satisfaction Index for E-Government. This goes to show that good things happen when you focus on findability.

But why hadn’t my clients identified and solved their findability problems sooner? Because, like so many other design teams, they viewed their responsibility from a top-down perspective. Can users find what they need from the home page? It’s an important question, but it ignores the fact that many users don’t start from the home page. Powerful search tools, directories, blogs, social bookmarks, and syndication services are moving deep linking and content sampling from exception to rule. Many of your users will never visit your home page. And some may not even realize the answers they want are on the Web. People often assume they’ll have to visit a library or ask a professional, and for lack of time or money, they get stuck. Can users find what they need from wherever they are? That’s the multi-channel communication question we should be asking.

At NCI, the team had to look beyond the narrow goals of web site design, to see their role in advancing the broader mission of disseminating cancer information to people in need. They had a blind spot when it came to findability, and it’s a weakness shared by many if not most organizations today. Executives want a web site that looks good. And thankfully, most now want a web site that’s usable. But few executives understand the Web and how people use it well enough to recognize the vital importance of findability.

This is no small oversight. In a marketplace that’s shifting from push to pull, findability is a big deal. As a pioneer of Internet search engine advertising, Overture recognized this opportunity early and capitalized on it to the tune of $1.6 billion (the value of their acquisition by Yahoo!). Paco Underhill, the

guru of the science of shopping, acknowledges this transition in his best-selling book, Why We Buy:

Generations ago, the commercial messages intended for consumers’ ears came in highly concentrated, reliable form. There were three TV networks, AM radio only, a handful of big-circulation national magazines and each town’s daily papers, which all adults read. Big brand-name goods were advertised in those media, and the message got through loud, clear and dependably. Today, we have remote controls and VCRs to allow us to skip all the ads if we choose to. There’s FM radio now, a plethora of magazines catering to each little special interest, a World Wide Web of infinitely expanding sites we can visit for information and entertainment and a shrinking base of newspaper readers, all of which means it is harder to reach consumers and convince them to buy anything at all.[*]

In a world where it’s getting harder to reach consumers, shouldn’t businesses make it easier for consumers to reach them? Yet, when it comes to findability, most business web sites have major problems. Poor information architecture. Weak compliance with web standards. No metadata. Content buried in databases that are invisible to search engines. From sales to support, many firms could get a great return by investing in findability.

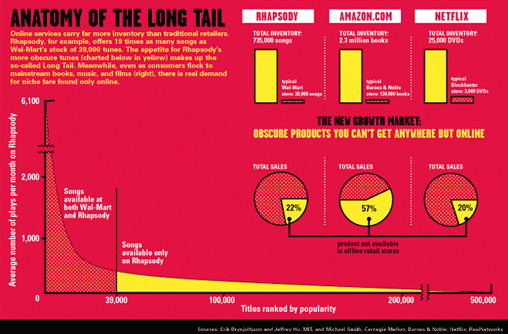

But the fault lines extend well beyond web design. Findability is transforming the marketplace. For those who pay attention, the signals of tectonic shift are self-evident in what Chris Anderson of Wired calls the Long Tail, shown in Figure 1-3. In his colorful analysis of the “millions of niche markets at the shallow end of the bitstream,” Anderson explains how the virtually unlimited selection of online catalogs is shaking up our economy:

What’s really amazing about the Long Tail is the sheer size of it. Combine enough non-hits on the Long Tail and you’ve got a market bigger than hits. Take books: the average Barnes & Noble carries 130,000 titles. Yet more than half of Amazon’s book sales come from outside its top 130,000 titles. Consider the implication...the market for books that are not even sold in the average bookstore is larger than the market for those that are.[*] [†]

As venture capitalist Kevin Laws puts it: “The biggest money is in the smallest sales.” In an economy where it takes almost nothing to produce and stock one more item, the competitive challenges and big wins are in findability. How do we reduce search costs and time to find? How do we use social software to drive demand down the Long Tail?

Amazon, eBay, Google, iTunes, and Netflix are all Long Tail. Each of these early adopters uses search in support of mass customization. They know you can’t buy what you can’t find. And they understand this is a tail that will ultimately wag the dog. How will your business respond? The search space is huge. The potential for top line growth is big. But you better jump now while there’s still plenty of room at the bottom.[*]

But wait. Don’t move too fast. Or you just might wander off a cliff. In matters of findability, the siren song of technology has lured many to destruction. Though our attention is drawn to the fast layers of hi-tech, the map to this maze is buried in the slow layers of human behavior and psychology. It’s not enough to focus on the I in IT. We must also lose the C in HCI. Because ambient findability is less about the computer than the complex interactions between humans and information.

Findability is the biggest story on the Web today, and its reach will only grow as the tidal waves of channel convergence and ubiquitous computing wash over our shores. We will use the Web to navigate a physical world that sparkles with embedded sensors and geospatial metadata, even as we diminish the need to move our bodies through space. Mobile devices will unite our data streams in an evolving dance of informed consumers seeking collective intelligence and inspiration. And in this ambient economy, findability will be a key source of competitive advantage. Finders, keepers; losers, weepers.

Paradise Lost

Have you ever been to Lost and Found ? It’s a shadowy place we discover only through loss. It’s filled with hats, mittens, watches, toys, and rings of gold and silver. And it smells of hope and fear and musty books. A child’s first visit is a powerful experience. A valued possession has been lost. Perhaps in the classroom or on the playground. A frantic search leads to tearful resignation. Finders, keepers; losers, weepers.

But wait. A classmate steps forward. Have you tried the Lost and Found? Understanding is instant. A place for lost things. That makes sense. A short walk to an office with a cardboard box under a table. There it is. That’s mine. A happy ending.

Of course, sometimes finders are keepers. Sometimes things get lost between the cracks. It depends what you lose and where and when. The idea of Lost and Found is universal. It’s a social institution that transcends place and time. But the instantiation is another matter. A cardboard box in your local school. A steel cage in a foreign airport. The idea adapts to suit its environment. Each instance is defined by location.

Or at least it was until that disruptive technology known as the Internet came along. People from all over can now report and seek items using the Internet Lost and Found. The site sports an international database of pet and property listings, and the stories of success touch the heart and mind. An 83-year-old woman recovers a beloved heirloom necklace. A 10-year-old boy is reunited with his English Springer Spaniel. Dogs, cats, watches, wallets. Lost in the world. Found in cyberspace. Our digital networks locate physical objects. Keyword search isn’t just for documents anymore. Technology has entered the shadow lands of Lost and Found, and we ain’t seen nothin’ yet.

Some speak of a coming techno-utopia, a magical era when all our problems will fade into the sunset. The end of poverty and starvation. No more sickness and disease. Global peace. Eternal life. In the words of Ernest Hemingway in The Sun Also Rises, isn’t it pretty to think so? The human condition won’t be untangled so easily, and technology is a double-edged sword. Arthur C. Clarke once said “any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.” His remark conjures both promise and peril.

We can be surprised and delighted by innovation. A vaccine for smallpox. A man on the moon. A computer through the eye of a needle. Sometimes anything seems possible, and yet it’s not. Technology remains subject to the laws of physics and the gravity of economics. Unfortunately, false prophets abound, and today’s technology is advanced enough that we have a hard time separating fact from fiction.

On the Web, these prophets claim that artificial intelligence will make it easy for us to find what we need, or better yet, for our digital agents and smart services to find us. Indeed, progress will come, but it won’t come so easy. Information anxiety will intensify, and we’ll spend more time, rather than less, searching for what we need.

These sober predictions derive not from the laws of physics but from the limits of language. For that’s what we talk about when we talk about findability. While the Web’s architecture rests on a solid foundation of code, its usefulness depends on the slippery slope of semantics. It’s all about words. Words as labels. Words as links. Keywords.

And words are messy little critters. Imprecise and undependable, their meaning shifts with context. One man’s paradise is another man’s oblivion. Synonyms, antonyms, homonyms, contranyms: the challenges of communication are part of the human condition, unsusceptible to the eager advances of technology.

Some speak of a coming techno-dystopia, a brave new world of more ignorance and less freedom. Librarians worry about students who never step foot in libraries, a dot.net generation that goes to Google when they need to read. One woman I met at a conference in Paris even accused the Internet of creating “a black hole in our cultural heritage.”

While sometimes funny, these fears aren’t irrational or insignificant, but they don’t keep me up at night. Because, when it comes to the Internet and the future of ambient findability, I’m an optimist. In Marshall McLuhan’s insight that the medium is the message, I see the power of the Internet to engage people as participants in the collaborative, productive enterprise of knowledge creation and dissemination. For information is ultimately about communication. As S.I. Hayakawa once wrote:

In addition to having developed language, human beings have also developed means of making, on clay tablets, bits of wood or stone, skins of animals, paper and microchips, more or less permanent marks and scratches that stand for language...Humans are no longer dependent for information upon direct experience alone. Instead of exploring the false trails others have explored and repeating their errors, they can go on from where others left off. Language makes progress possible.[*]

We take language and the Internet for granted, yet they are testaments to human ingenuity and our ability to enlist selfish genes in remarkable acts of cooperation. So, as the Web rolls on, I don’t fear the loss of culture. On the contrary, the Web makes our cultural heritage more accessible. The dialogues of Plato, the sonnets of Shakespeare, and the poetry of Paradise Lost are all findable and accessible, even from a beach in Newport.

Yesterday will not be lost, and we won’t find paradise in the morning. But tomorrow will be different. Findability is at the center of a quiet revolution in how we define authority, allocate trust, and make decisions. We won’t forget the past, but we will reinvent the future. And as we wander into the uncharted territory between the land of atoms and the sea of bits, we should bring a compass, or even better, a Treo, because the journey transforms the destination, and it’s easy to become lost in reflection.

[*] Information Literacy Competency Standards. American Library Association: http://www.ala.org/ala/acrl/acrlstandards/informationliteracycompetency.htm.

[*] Why We Buy by Paco Underhill. Simon & Schuster (1999), p. 31-32.

[*] “The Long Tail” by Chris Anderson. Available at http://www.wired.com/wired/archive/12.10/tail.html.

[†] On August 3, 2005, Chris Anderson retracted his estimate that 57% of Amazon’s book sales are in the Long Tail. Current estimates are in the less shocking but still impressive 25%-40% range. For the full story, see http://longtail.typepad.com/the_long_tail/2005/08/a_methodology_f.html.

[*] Inspired by the words of physics genius Richard Feynman, whose 1959 talk entitled “There’s Plenty of Room at the Bottom” launched the field of nanotechnology.

[*] Language in Thought and Action by S.I. Hayakawa. Harcourt (1939), p. 6–7.

Get Ambient Findability now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.