Chapter 1. Introduction to Apollo

Apollo is a new cross-platform desktop runtime being developed by Adobe that allows web developers to use web technologies to build and deploy Rich Internet Applications and web applications to the desktop.

In order to better understand what Apollo enables, and which problems it tries to address, it is useful to first take a quick look over at the (relatively short) history of web applications.

A Short History of Web Applications

Over the past couple of years, there has been an accelerating trend of applications moving from the desktop to the web browser. This has been driven by a number of factors, which include:

The growth of the Internet as a communication medium

The relative ease of deployment of web applications

The ability to target multiple operating systems via the browser

The maturity of higher-level client technologies, such the browser and the Flash Player runtime

Early web applications were built primarily with HTML and JavaScript, which, for the most part, heavily relied on client/server interactions and page refreshes. This page refresh model was consistent with the document-based metaphor for which the browser was originally designed, but provided a relatively poor user experience when displaying applications.

However, with the maturation of the Flash Player runtime, and more recently Ajax-type functionality in the browser, it became possible for developers to begin breaking away from page-based application flows. In short, developers began to be able to offer richer application experiences via the browser. In a whitepaper from March 2002, Macromedia coined the term Rich Internet Application (RIA), to describe these new types of applications in browsers, which “blend content, application logic and communications...to make the Internet more usable and enjoyable.” These applications provided richer, more desktop-like experiences, while still retaining the core cross-platform nature of the Web:

Internet applications are all about reach. The promise of the web is one of content and applications anywhere, regardless of the platform or device. Rich clients must embrace and support all popular desktop operating systems, as well as the broadest range of emerging device platforms such as smart phones, PDAs, set-top boxes, game consoles, and Internet appliances.

Tip

You can find the complete whitepaper and more information on RIAs at: http://download.macromedia.com/pub/flash/whitepapers/richclient.pdf

The paper goes on to list some features that define RIAs:

Provide an efficient, high performance runtime for executing code, content, and communications.

Integrate content, communications, and application interfaces into a common environment.

Provide powerful and extensible object models for interactivity.

Enable rapid application development through components and re-use.

Enable the use of web and data services provided by application servers.

Embrace connected and disconnected clients.

Enable easy deployment on multiple platforms and devices.

This movement toward providing richer, more desktop-like application experiences in the browser (enabled by the Flash Player runtime, and more recently by Ajax techniques) has led to an explosion of web applications.

Today the web has firmly established itself as an application deployment platform that offers benefits to both developers and end users. These benefits include the ability to:

Target multiple platforms and operating systems.

Develop with relatively high-level programming and layout languages.

Allow end users to access their applications and data from virtually any Internet-connected computer.

The growth of web applications can be seen in both the Web 2.0 movement, which consists almost entirely of web based applications and APIs, as well as the adoption of web applications as a core business model of major companies and organizations.

Problems with Delivering Applications via the Browser

As web applications have become more complex, they have begun to push the boundaries of both the capabilities of the browser and the usability of the application. As their popularity grows, these issues become more apparent and important and highlight that there are still a number of significant issues for both developers and end users when deploying applications via the browser.

The web browser was original designed to deliver and display HTML-based documents. Indeed, the basic design of the browser has not significantly shifted from this purpose. This fundamental conflict between document- and application-focused functionality creates a number of problems when deploying applications via the browser.

Conflicting UI

Applications deployed via the browser have their own user interface, which often conflicts with the user interface of the browser. This application within an application model often results in user interfaces that conflict with and contradict each other. This can lead to user confusion in the best cases, and application failure in the worst cases. The classic example of this is the browser’s Back button. The Back button makes sense when browsing documents, but it does not always make sense in the context of an application. Although there are a number of solutions that attempt to solve this problem, they are applied to applications inconsistently; users may not know whether a specific application supports the Back button, or whether it will force their application to unload, causing it to lose its state and data.

Distance from the Desktop

Due in part to the web security model (which restricts access to the users machine), applications that run in the browser often do not support the type of user interactions with the operating system that users expect from applications. For example, you cannot drag a file into a browser-based application and have the application act on that file. Nor can the web application interact with other applications on the user’s computer.

RIAs have tried to improve on this by making richer, more desktop-like interfaces possible in the browser, but they have not been able to overcome the fundamental limitations and separation of the browser from the desktop.

Primarily Online Experience

Because web applications are delivered from a server and do not reside on the users machine, web applications are a primarily online experience. While there are attempts underway to make offline web-based applications possible, they do not provide a consistent development model, they fail to work across different browsers, and they often require the user to interact with and manage their application and browser in complex and unexpected ways.

Lowest Common Denominator

Finally, as applications become richer and more complex and begin to push the boundaries of JavaScript and DHTML, developers are increasingly faced with differences in browser functionality and APIs. While these issues can often be overcome with browser-specific code, it leads to code that is more difficult to maintain and scale, and takes time away from function-driven development.

While JavaScript frameworks are a popular way to help address these issues, they can offer only the functionality provided by the browser, and often resort to the lowest common denominator of features between browsers to ease the development model. While this issue doesn’t affect Flash-based RIAs, the end result for JavaScript- or DHTML-based applications is a lowest common denominator user experience and interaction model, as well as increased development, testing, and deployment costs for the developer.

The fact that web applications have flourished despite these drawbacks is a testament to the attractiveness of having a platform with a good development model that has the ability to deliver applications to multiple operating systems. A platform that offered the reach and development model of the browser, while providing the functionality and richness of a desktop application, would provide the best of both worlds. This is what Apollo aims to do.

Introducing the Apollo Runtime

So, what is Apollo, and how can it make web application development and deployment better?

Apollo is the code name for a new cross-operating system runtime being developed by Adobe that allows web developers to leverage their existing web development skills (such as Flash, Flex, HTML, JavaScript, and PDF) to build and deploy Rich Internet Applications and content to the desktop.

In essence, it provides a platform in between the desktop and the browser, which combines the reach and ease of development of the web model with the functionality and richness of the desktop model.

Note

Apollo is the code name for the project. The final name had not yet been announced at the time of this writing.

It is important to step back for a second and point out what Apollo is not. Apollo is not a general desktop runtime meant to compete with lower-level application runtimes. This means that you probably wouldn’t want to build Photoshop on top of Apollo. Apollo’s primary use case is enabling Rich Internet and web applications to be deployed to the desktop. This is a very important but subtle distinction, as enabling RIAs on the desktop is the primary use case driving the Apollo 1.0 feature set.

At its core, Apollo is built on top of web technologies, which allow web developers to develop for and deploy to the desktop using the same technologies and development models that they use today when deploying applications on the Web.

Primary Apollo Technologies

There are three primary technologies included within Apollo, which fall into two distinct categories: application technologies and document technologies.

Primary Application Technologies

Application technologies are technologies that can be used as the basis of an application within Apollo. Apollo contains two primary application technologies, Flash and HTML, both of which can be used on their own to build and deploy Apollo applications.

Flash

One of the core technologies Apollo is built on is the Flash Player. Specifically, Apollo is built on top of Flash Player 9, which includes the ECMAScript-based ActionScript 3 as well as the open source Tamarin virtual machine (which will be used to interpret JavaScript in future versions of Firefox).

Tip

You can find more information on the open source Tamarin project at on the Mozilla website site at http://www.mozilla.org/projects/tamarin/

Not only are all of the existing Flash Player APIs available within Apollo, but some of those APIs have also been expanded and/or enhanced. Some of the functionality that the Flash Player provides to Apollo includes:

Of course, the Flex 2 framework is built on top of ActionScript 3, which means that you can also take advantage of all of the features and functionality that Flex offers in order to build Apollo applications.

HTML

The second application technology within Apollo is HTML. This is a full HTML rendering engine, which includes support for:

Yes, you read that right. You don’t have to use Flash to build Apollo applications. You can build a full-featured application using just HTML and JavaScript. This usually surprises some developers who expect Apollo to focus only on Flash. However, at its core, Apollo is a runtime targeted at web developers using web technologies—and what is more of a web technology than HTML and JavaScript?

The HTML engine used within Apollo is the open source WebKit engine. This is the engine behind a number of browsers, including KHTML on KDE and Safari on Mac OS X.

Tip

You can find more information on the WebKit open source project at http://www.webkit.org

Why WebKit?

Adobe spent a considerable amount of time researching which HTML engine to use within Apollo and used a number of criteria that ultimately led them to settle on WebKit.

Open project

Adobe knew from the very beginning that it did not want to create and maintain its own HTML rendering engine. Not only would this be an immense amount of work, but it would also make it difficult for developers, who would then have to become familiar with all of the quirks of yet another HTML engine.

WebKit provides Apollo with a full-featured HTML engine that is under continuous development by a robust development community that includes individual developers as well as large companies such as Nokia and Apple. This allows Adobe to focus on bug fixes and features, and also means that Adobe can actively contribute back to WebKit, while also taking advantage of the contributions made by other members of the WebKit project.

Proven technology that web developers know

As discussed earlier, one of the biggest problems with complex web development is ensuring that content works consistently across browsers. While something may work perfectly in Firefox on the Mac, it may completely fail in Internet Explorer on Windows. Because of this, testing and debugging browser-based content can be a nightmare for developers.

Adobe wanted to ensure that developers were already familiar with the HTML engine used within Apollo, and that they did not have to learn new all of the quirks and bugs of a new engine. Since Safari (which is built on top of WebKit) is the default browser for Mac OS X, developers should be familiar with developing for it.

Minimum effect on Apollo runtime size

The target size for Apollo is between 5 and 9 MB. The WebKit code base was well-written and organized and had a minimal impact on the final Apollo runtime size. Indeed, the current runtime size with both Flash and HTML is just a little over 5 MB.

Proven ability to run on mobile devices

While the first release of Apollo runs only on personal computers, the long-term vision is to extend the Apollo runtime from the desktop to cell phones and other devices. WebKit has a proven ability to run on such devices and has been ported to cell phones by both Nokia and Apple.

Primary Document Technology

Document technologies within Apollo refer to technologies whose primary purpose is for the rendering and interaction with electronic documents.

PDF and HTML are the primary document technologies available within Apollo.

PDF functionality is not included in Alpha 1 of Apollo, so we cannot go into too much detail of how it is implemented. However, in general Apollo applications, both Flash- and HTML-based, will be able to leverage and interact with PDF content.

HTML

HTML was originally designed as a document technology, and today it provides rich and robust control over content and text layout and styling. HTML can be used as a document technology within Apollo—both within an existing HTML application as well as within a Flash-based application.

What Does An Apollo Application Contain?

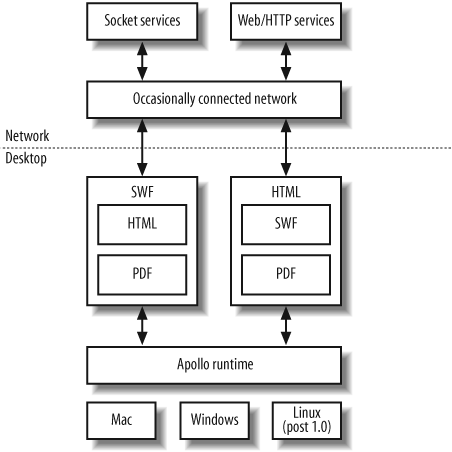

Now that we know what technologies are available to applications running on top of the Apollo runtime (see Figure 1-1), let’s look at how those technologies can be combined to build an Apollo application.

Applications can consist of the following combinations of technologies:

Flash only (including Flex)

Flash-based with HTML content

HTML/JavaScript only

HTML/JavaScript-based with Flash content

All combinations can also leverage PDF content

Technology Integration and Script Bridging

Because WebKit and the Flash Player are both included within the runtime, they are integrated together on a very low level. For example, when HTML is included within Flash content, it is actually rendered via the Flash display pipeline, which, among other things, means that anything that you can do to a bitmap within Flash (blur, rotate, transform, etc.) can also be done to HTML.

This low-level integration also applies to the script engines within Apollo (that run ActionScript and JavaScript). Apollo provides script bridging between the two languages and environments, which makes the following possible:

JavaScript code to call ActionScript APIs

ActionScript code to call JavaScript APIs

ActionScript code to directly manipulate the HTML DOM

Event registration both ways between JavaScript and ActionScript

Note that the script bridging is “pass by reference.” So when passing an object instance from ActionScript to JavaScript (or vice versa), changes to that instance in one environment will affect the instance in the other environment. Among other things, this makes it possible to maintain a reference to HTML nodes from within ActionScript and modify them, or to register and listen for events.

This low-level script bridging between the two environments makes it very easy for developers to create applications that are a combination of both HTML and Flash.

Tip

Script Bridging is covered in more detail in Chapter 4.

The end result of all of this is that if you are a web developer, then you already have all of the skills necessary to build an Apollo application.

Apollo Functionality

If Apollo did not provide additional functionality and APIs and simply allowed web applications to run on the desktop, it would not be at all compelling. Fortunately, Apollo provides a rich set of programming APIs, as well as close integration with the desktop that allows developers to build applications that take advantage of the fact that they’re running on the user’s desktop.

Apollo Programming APIs

In addition to all of the functionality and APIs already offered by the Flash Player and WebKit engine, Apollo provides additional functionality and APIs.

Some of the new functionality includes, but is not limited to:

Complete file I/O API

Complete native windowing API

Complete native menuing API

Online/Offline APIs to detect when network connectivity has changed

Data Caching and Syncing APIs to make it easier to develop applications that work on- and offline.

Complete control over application chrome

Local storage/settings APIs

System notification APIs (that tie into OS-specific notification mechanisms)

Application update APIs

Note that functionality may be implemented directly within the Apollo runtime or on the framework layer (in Flex and JavaScript), or by using a combination of both.

Apollo Desktop Integration

As discussed earlier, applications deployed via the browser cannot always support the same user interactions as desktop applications. This leads to applications that can be cumbersome for the user to interact with, as they do not allow the type of application interactions with which users are familiar.

Because an Apollo application is a desktop application, it is able to provide the type of application interactions and experience that users expect from an application. This functionality includes, but is not limited to:

Appropriate install/uninstall rituals

Desktop install touchpoints (i.e., shortcuts, etc.)

Rich drag-and-drop support:

Between operating system and Apollo applications Between Apollo applications Between native applications and Apollo applications Rich clipboard support

System notifications

Icons

Ability for applications to run in the background

Once installed, an Apollo application is just another native application, which means that the operating system and users can interact with it as it does with any other application. For example, things such as OS-level application pre-fetching and switching work the same with Apollo applications as they do with native applications.

The goal is that the end user doesn’t know they are running an application that leverages Apollo. He should be able to interact with an Apollo application in the same way that he interacts with any other application running on his desktop.

Apollo Development Toolset

One of the reasons web applications have been successful is that they allow developers to easily deploy applications that users can run regardless of which OS they are on. Whether Mac, Windows, Linux, Solaris, or cell phones, web applications provide reach.

However, success is based not only on cross-platform deployment, but also on the cross-platform nature of the development environment. This ensures that any developer can develop for—and leverage—the technology. Neither the runtime nor the development tools are tied to a specific OS.

The same is true of Apollo. Not only does Apollo provide the cross-platform reach of web applications, but, just as importantly, Apollo applications can be developed and packaged on virtually any operating system.

In fact, Apollo itself does not have a compiler or specialized IDE. Apollo applications just consist of web content, such as Flash and HTML. Any tool that can edit an HTML or JavaScript file can also be used to create an Apollo application.

Because Apollo applications are built with existing web technologies such as HTML and Flash, you can use the same tools that you use to create browser-based content to create Apollo applications. The Apollo SDK provides a number of free command-line tools that make it possible to test, debug, and package Apollo applications with virtually any web development and design tool.

|

ADL |

Allows Apollo applications to be run without having to first install them |

|

ADT |

Packages Apollo applications into distributable installation packages |

While Adobe will be adding support to its own web development and design tools for authoring Apollo content, they are not required. Using the Apollo command-line tools, you can create an Apollo application with any web development tool. You can use the same web development and design tools that you are already using today.

Tip

The Development Workflow will be covered in depth in Chapter 2.

Is Apollo the End of Web Applications in the Browser?

So, by this point, you may be saying to yourself, “Gee, Apollo sure sounds great! Why would anyone ever want to deploy an application to the browser again? Is Apollo the end of web applications within the browser?”

No.

Let’s repeat that again: no.

Apollo solves most of the problems with deploying web applications via the browser. However, there are still advantages to deploying applications via the browser. The fact that there are so many web applications despite the disadvantages discussed earlier is a testament to the advantages of running within the browser. When those advantages outweigh the disadvantages, developers will still deploy their applications via the web browser.

But is it not necessarily an either/or question. Because Apollo applications are built using web technologies, the application that you deploy via the web browser can be quickly turned into an Apollo application. You can have a web-based version that provides the browser-based functionality, and then also have an Apollo-based version that takes advantage of running on the desktop. Both versions could leverage the same technologies, languages, and code base.

Apollo applications complement web applications. They do not replace them.

Get Apollo for Adobe Flex Developers Pocket Guide now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.