Chapter 1. Domain Modeling

This chapter looks into how we can model business processes with code, in a way that’s highly compatible with TDD. We’ll discuss why domain modeling matters, and we’ll look at a few key patterns for modeling domains: Entity, Value Object, and Domain Service.

Figure 1-1 is a simple visual placeholder for our Domain Model pattern. We’ll fill in some details in this chapter, and as we move on to other chapters, we’ll build things around the domain model, but you should always be able to find these little shapes at the core.

Figure 1-1. A placeholder illustration of our domain model

What Is a Domain Model?

In the introduction, we used the term business logic layer to describe the central layer of a three-layered architecture. For the rest of the book, we’re going to use the term domain model instead. This is a term from the DDD community that does a better job of capturing our intended meaning (see the next sidebar for more on DDD).

The domain is a fancy way of saying the problem you’re trying to solve. Your authors currently work for an online retailer of furniture. Depending on which system you’re talking about, the domain might be purchasing and procurement, or product design, or logistics and delivery. Most programmers spend their days trying to improve or automate business processes; the domain is the set of activities that those processes support.

A model is a map of a process or phenomenon that captures a useful property. Humans are exceptionally good at producing models of things in their heads. For example, when someone throws a ball toward you, you’re able to predict its movement almost unconsciously, because you have a model of the way objects move in space. Your model isn’t perfect by any means. Humans have terrible intuitions about how objects behave at near-light speeds or in a vacuum because our model was never designed to cover those cases. That doesn’t mean the model is wrong, but it does mean that some predictions fall outside of its domain.

The domain model is the mental map that business owners have of their businesses. All business people have these mental maps—they’re how humans think about complex processes.

You can tell when they’re navigating these maps because they use business speak. Jargon arises naturally among people who are collaborating on complex systems.

Imagine that you, our unfortunate reader, were suddenly transported light years away from Earth aboard an alien spaceship with your friends and family and had to figure out, from first principles, how to navigate home.

In your first few days, you might just push buttons randomly, but soon you’d learn which buttons did what, so that you could give one another instructions. “Press the red button near the flashing doohickey and then throw that big lever over by the radar gizmo,” you might say.

Within a couple of weeks, you’d become more precise as you adopted words to describe the ship’s functions: “Increase oxygen levels in cargo bay three” or “turn on the little thrusters.” After a few months, you’d have adopted language for entire complex processes: “Start landing sequence” or “prepare for warp.” This process would happen quite naturally, without any formal effort to build a shared glossary.

So it is in the mundane world of business. The terminology used by business stakeholders represents a distilled understanding of the domain model, where complex ideas and processes are boiled down to a single word or phrase.

When we hear our business stakeholders using unfamiliar words, or using terms in a specific way, we should listen to understand the deeper meaning and encode their hard-won experience into our software.

We’re going to use a real-world domain model throughout this book, specifically a model from our current employment. MADE.com is a successful furniture retailer. We source our furniture from manufacturers all over the world and sell it across Europe.

When you buy a sofa or a coffee table, we have to figure out how best to get your goods from Poland or China or Vietnam and into your living room.

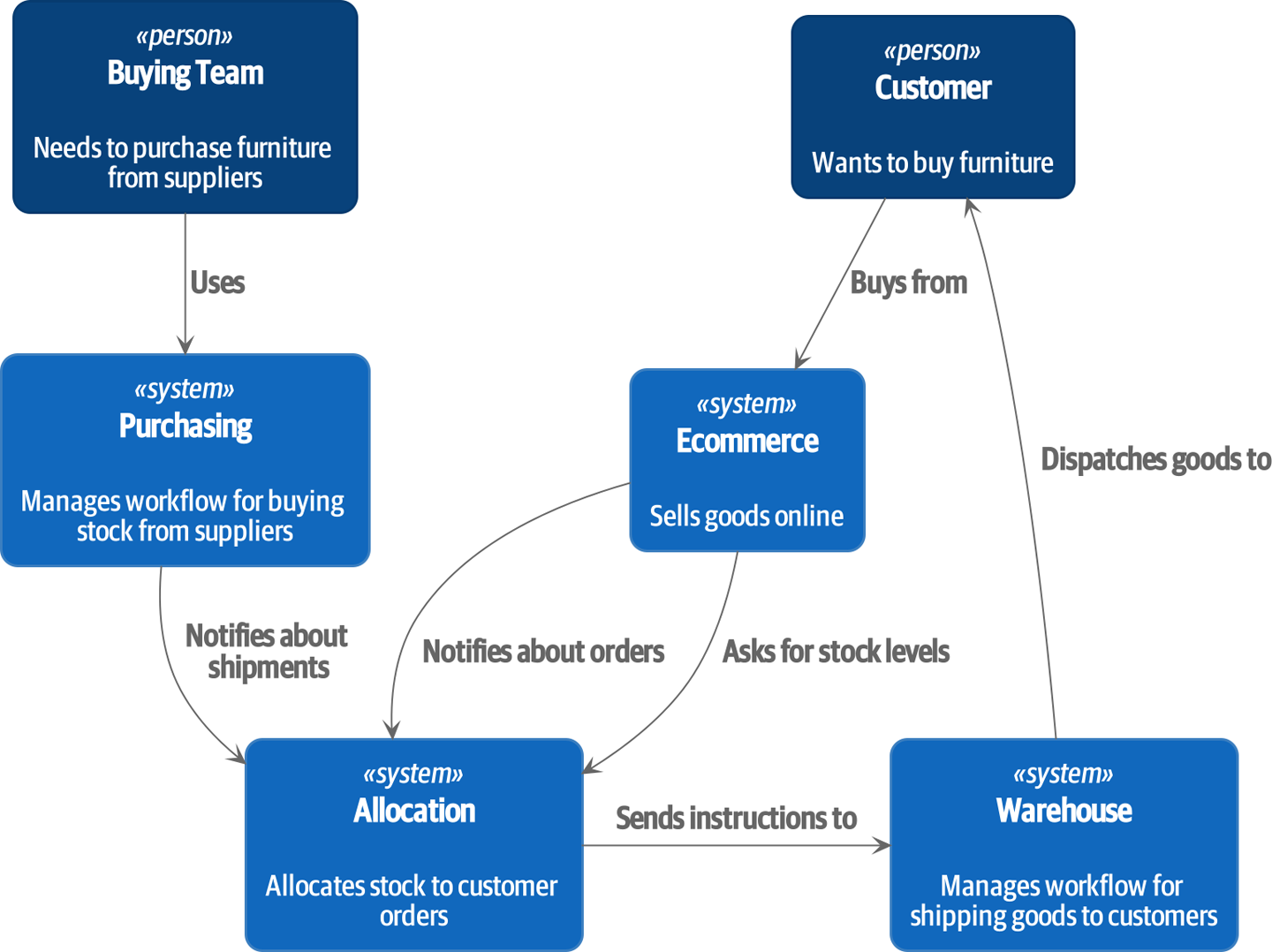

At a high level, we have separate systems that are responsible for buying stock, selling stock to customers, and shipping goods to customers. A system in the middle needs to coordinate the process by allocating stock to a customer’s orders; see Figure 1-2.

Figure 1-2. Context diagram for the allocation service

[plantuml, apwp_0102] @startuml Allocation Context Diagram !include images/C4_Context.puml System(systema, "Allocation", "Allocates stock to customer orders") Person(customer, "Customer", "Wants to buy furniture") Person(buyer, "Buying Team", "Needs to purchase furniture from suppliers") System(procurement, "Purchasing", "Manages workflow for buying stock from suppliers") System(ecom, "E-commerce", "Sells goods online") System(warehouse, "Warehouse", "Manages workflow for shipping goods to customers.") Rel(buyer, procurement, "Uses") Rel(procurement, systema, "Notifies about shipments") Rel(customer, ecom, "Buys from") Rel(ecom, systema, "Asks for stock levels") Rel(ecom, systema, "Notifies about orders") Rel_R(systema, warehouse, "Sends instructions to") Rel_U(warehouse, customer, "Dispatches goods to") @enduml

For the purposes of this book, we’re imagining that the business decides to implement an exciting new way of allocating stock. Until now, the business has been presenting stock and lead times based on what is physically available in the warehouse. If and when the warehouse runs out, a product is listed as “out of stock” until the next shipment arrives from the manufacturer.

Here’s the innovation: if we have a system that can keep track of all our shipments and when they’re due to arrive, we can treat the goods on those ships as real stock and part of our inventory, just with slightly longer lead times. Fewer goods will appear to be out of stock, we’ll sell more, and the business can save money by keeping lower inventory in the domestic warehouse.

But allocating orders is no longer a trivial matter of decrementing a single quantity in the warehouse system. We need a more complex allocation mechanism. Time for some domain modeling.

Exploring the Domain Language

Understanding the domain model takes time, and patience, and Post-it notes. We have an initial conversation with our business experts and agree on a glossary and some rules for the first minimal version of the domain model. Wherever possible, we ask for concrete examples to illustrate each rule.

We make sure to express those rules in the business jargon (the ubiquitous language in DDD terminology). We choose memorable identifiers for our objects so that the examples are easier to talk about.

“Some Notes on Allocation” shows some notes we might have taken while having a conversation with our domain experts about allocation.

Unit Testing Domain Models

We’re not going to show you how TDD works in this book, but we want to show you how we would construct a model from this business conversation.

Here’s what one of our first tests might look like:

A first test for allocation (test_batches.py)

deftest_allocating_to_a_batch_reduces_the_available_quantity():batch=Batch("batch-001","SMALL-TABLE",qty=20,eta=date.today())line=OrderLine('order-ref',"SMALL-TABLE",2)batch.allocate(line)assertbatch.available_quantity==18

The name of our unit test describes the behavior that we want to see from the system, and the names of the classes and variables that we use are taken from the business jargon. We could show this code to our nontechnical coworkers, and they would agree that this correctly describes the behavior of the system.

And here is a domain model that meets our requirements:

First cut of a domain model for batches (model.py)

@dataclass(frozen=True)classOrderLine:orderid:strsku:strqty:intclassBatch:def__init__(self,ref:str,sku:str,qty:int,eta:Optional[date]):self.reference=refself.sku=skuself.eta=etaself.available_quantity=qtydefallocate(self,line:OrderLine):self.available_quantity-=line.qty

OrderLineis an immutable dataclass with no behavior.2

We’re not showing imports in most code listings, in an attempt to keep them clean. We’re hoping you can guess that this came via

from dataclasses import dataclass; likewise,typing.Optionalanddatetime.date. If you want to double-check anything, you can see the full working code for each chapter in its branch (e.g., chapter_01_domain_model).

Type hints are still a matter of controversy in the Python world. For domain models, they can sometimes help to clarify or document what the expected arguments are, and people with IDEs are often grateful for them. You may decide the price paid in terms of readability is too high.

Our implementation here is trivial: a Batch just wraps an integer

available_quantity, and we decrement that value on allocation. We’ve written

quite a lot of code just to subtract one number from another, but we think that modeling our

domain precisely will pay off.3

Let’s write some new failing tests:

Testing logic for what we can allocate (test_batches.py)

defmake_batch_and_line(sku,batch_qty,line_qty):return(Batch("batch-001",sku,batch_qty,eta=date.today()),OrderLine("order-123",sku,line_qty))deftest_can_allocate_if_available_greater_than_required():large_batch,small_line=make_batch_and_line("ELEGANT-LAMP",20,2)assertlarge_batch.can_allocate(small_line)deftest_cannot_allocate_if_available_smaller_than_required():small_batch,large_line=make_batch_and_line("ELEGANT-LAMP",2,20)assertsmall_batch.can_allocate(large_line)isFalsedeftest_can_allocate_if_available_equal_to_required():batch,line=make_batch_and_line("ELEGANT-LAMP",2,2)assertbatch.can_allocate(line)deftest_cannot_allocate_if_skus_do_not_match():batch=Batch("batch-001","UNCOMFORTABLE-CHAIR",100,eta=None)different_sku_line=OrderLine("order-123","EXPENSIVE-TOASTER",10)assertbatch.can_allocate(different_sku_line)isFalse

There’s nothing too unexpected here. We’ve refactored our test suite so that we

don’t keep repeating the same lines of code to create a batch and a line for

the same SKU; and we’ve written four simple tests for a new method

can_allocate. Again, notice that the names we use mirror the language of our

domain experts, and the examples we agreed upon are directly written into code.

We can implement this straightforwardly, too, by writing the can_allocate

method of Batch:

A new method in the model (model.py)

defcan_allocate(self,line:OrderLine)->bool:returnself.sku==line.skuandself.available_quantity>=line.qty

So far, we can manage the implementation by just incrementing and decrementing

Batch.available_quantity, but as we get into deallocate() tests, we’ll be

forced into a more intelligent solution:

This test is going to require a smarter model (test_batches.py)

deftest_can_only_deallocate_allocated_lines():batch,unallocated_line=make_batch_and_line("DECORATIVE-TRINKET",20,2)batch.deallocate(unallocated_line)assertbatch.available_quantity==20

In this test, we’re asserting that deallocating a line from a batch has no effect

unless the batch previously allocated the line. For this to work, our Batch

needs to understand which lines have been allocated. Let’s look at the

implementation:

The domain model now tracks allocations (model.py)

classBatch:def__init__(self,ref:str,sku:str,qty:int,eta:Optional[date]):self.reference=refself.sku=skuself.eta=etaself._purchased_quantity=qtyself._allocations=set()# type: Set[OrderLine]defallocate(self,line:OrderLine):ifself.can_allocate(line):self._allocations.add(line)defdeallocate(self,line:OrderLine):iflineinself._allocations:self._allocations.remove(line)@propertydefallocated_quantity(self)->int:returnsum(line.qtyforlineinself._allocations)@propertydefavailable_quantity(self)->int:returnself._purchased_quantity-self.allocated_quantitydefcan_allocate(self,line:OrderLine)->bool:returnself.sku==line.skuandself.available_quantity>=line.qty

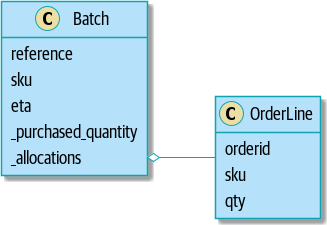

Figure 1-3 shows the model in UML.

Figure 1-3. Our model in UML

[plantuml, apwp_0103, config=plantuml.cfg]

left to right direction

hide empty members

class Batch {

reference

sku

eta

_purchased_quantity

_allocations

}

class OrderLine {

orderid

sku

qty

}

Batch::_allocations o-- OrderLine

Now we’re getting somewhere! A batch now keeps track of a set of allocated

OrderLine objects. When we allocate, if we have enough available quantity, we

just add to the set. Our available_quantity is now a calculated property:

purchased quantity minus allocated quantity.

Yes, there’s plenty more we could do. It’s a little disconcerting that

both allocate() and deallocate() can fail silently, but we have the

basics.

Incidentally, using a set for ._allocations makes it simple for us

to handle the last test, because items in a set are unique:

Last batch test! (test_batches.py)

deftest_allocation_is_idempotent():batch,line=make_batch_and_line("ANGULAR-DESK",20,2)batch.allocate(line)batch.allocate(line)assertbatch.available_quantity==18

At the moment, it’s probably a valid criticism to say that the domain model is too trivial to bother with DDD (or even object orientation!). In real life, any number of business rules and edge cases crop up: customers can ask for delivery on specific future dates, which means we might not want to allocate them to the earliest batch. Some SKUs aren’t in batches, but ordered on demand directly from suppliers, so they have different logic. Depending on the customer’s location, we can allocate to only a subset of warehouses and shipments that are in their region—except for some SKUs we’re happy to deliver from a warehouse in a different region if we’re out of stock in the home region. And so on. A real business in the real world knows how to pile on complexity faster than we can show on the page!

But taking this simple domain model as a placeholder for something more complex, we’re going to extend our simple domain model in the rest of the book and plug it into the real world of APIs and databases and spreadsheets. We’ll see how sticking rigidly to our principles of encapsulation and careful layering will help us to avoid a ball of mud.

Dataclasses Are Great for Value Objects

We’ve used line liberally in the previous code listings, but what is a

line? In our business language, an order has multiple line items, where

each line has a SKU and a quantity. We can imagine that a simple YAML file

containing order information might look like this:

Order info as YAML

Order_reference:12345Lines:-sku:RED-CHAIRqty:25-sku:BLU-CHAIRqty:25-sku:GRN-CHAIRqty:25

Notice that while an order has a reference that uniquely identifies it, a

line does not. (Even if we add the order reference to the OrderLine class,

it’s not something that uniquely identifies the line itself.)

Whenever we have a business concept that has data but no identity, we often choose to represent it using the Value Object pattern. A value object is any domain object that is uniquely identified by the data it holds; we usually make them immutable:

OrderLine is a value object

@dataclass(frozen=True)classOrderLine:orderid:OrderReferencesku:ProductReferenceqty:Quantity

One of the nice things that dataclasses (or namedtuples) give us is value

equality, which is the fancy way of saying, “Two lines with the same orderid,

sku, and qty are equal.”

More examples of value objects

fromdataclassesimportdataclassfromtypingimportNamedTuplefromcollectionsimportnamedtuple@dataclass(frozen=True)className:first_name:strsurname:strclassMoney(NamedTuple):currency:strvalue:intLine=namedtuple('Line',['sku','qty'])deftest_equality():assertMoney('gbp',10)==Money('gbp',10)assertName('Harry','Percival')!=Name('Bob','Gregory')assertLine('RED-CHAIR',5)==Line('RED-CHAIR',5)

These value objects match our real-world intuition about how their values work. It doesn’t matter which £10 note we’re talking about, because they all have the same value. Likewise, two names are equal if both the first and last names match; and two lines are equivalent if they have the same customer order, product code, and quantity. We can still have complex behavior on a value object, though. In fact, it’s common to support operations on values; for example, mathematical operators:

Math with value objects

fiver=Money('gbp',5)tenner=Money('gbp',10)defcan_add_money_values_for_the_same_currency():assertfiver+fiver==tennerdefcan_subtract_money_values():asserttenner-fiver==fiverdefadding_different_currencies_fails():withpytest.raises(ValueError):Money('usd',10)+Money('gbp',10)defcan_multiply_money_by_a_number():assertfiver*5==Money('gbp',25)defmultiplying_two_money_values_is_an_error():withpytest.raises(TypeError):tenner*fiver

Value Objects and Entities

An order line is uniquely identified by its order ID, SKU, and quantity; if we change one of those values, we now have a new line. That’s the definition of a value object: any object that is identified only by its data and doesn’t have a long-lived identity. What about a batch, though? That is identified by a reference.

We use the term entity to describe a domain object that has long-lived

identity. On the previous page, we introduced a Name class as a value object.

If we take the name Harry Percival and change one letter, we have the new

Name object Barry Percival.

It should be clear that Harry Percival is not equal to Barry Percival:

A name itself cannot change…

deftest_name_equality():assertName("Harry","Percival")!=Name("Barry","Percival")

But what about Harry as a person? People do change their names, and their marital status, and even their gender, but we continue to recognize them as the same individual. That’s because humans, unlike names, have a persistent identity:

But a person can!

classPerson:def__init__(self,name:Name):self.name=namedeftest_barry_is_harry():harry=Person(Name("Harry","Percival"))barry=harrybarry.name=Name("Barry","Percival")assertharryisbarryandbarryisharry

Entities, unlike values, have identity equality. We can change their values, and they are still recognizably the same thing. Batches, in our example, are entities. We can allocate lines to a batch, or change the date that we expect it to arrive, and it will still be the same entity.

We usually make this explicit in code by implementing equality operators on entities:

Implementing equality operators (model.py)

classBatch:...def__eq__(self,other):ifnotisinstance(other,Batch):returnFalsereturnother.reference==self.referencedef__hash__(self):returnhash(self.reference)

Python’s __eq__ magic method

defines the behavior of the class for the == operator.5

For both entity and value objects, it’s also worth thinking through how

__hash__ will work. It’s the magic method Python uses to control the

behavior of objects when you add them to sets or use them as dict keys;

you can find more info in the Python docs.

For value objects, the hash should be based on all the value attributes,

and we should ensure that the objects are immutable. We get this for

free by specifying @frozen=True on the dataclass.

For entities, the simplest option is to say that the hash is None, meaning

that the object is not hashable and cannot, for example, be used in a set.

If for some reason you decide you really do want to use set or dict operations

with entities, the hash should be based on the attribute(s), such as

.reference, that defines the entity’s unique identity over time. You should

also try to somehow make that attribute read-only.

Warning

This is tricky territory; you shouldn’t modify __hash__ without

also modifying __eq__. If you’re not sure what you’re doing,

further reading is suggested.

“Python Hashes and Equality” by our tech reviewer Hynek Schlawack is a good place to start.

Not Everything Has to Be an Object: A Domain Service Function

We’ve made a model to represent batches, but what we actually need to do is allocate order lines against a specific set of batches that represent all our stock.

Sometimes, it just isn’t a thing.

Eric Evans, Domain-Driven Design

Evans discusses the idea of Domain Service operations that don’t have a natural home in an entity or value object.6 A thing that allocates an order line, given a set of batches, sounds a lot like a function, and we can take advantage of the fact that Python is a multiparadigm language and just make it a function.

Let’s see how we might test-drive such a function:

Testing our domain service (test_allocate.py)

deftest_prefers_current_stock_batches_to_shipments():in_stock_batch=Batch("in-stock-batch","RETRO-CLOCK",100,eta=None)shipment_batch=Batch("shipment-batch","RETRO-CLOCK",100,eta=tomorrow)line=OrderLine("oref","RETRO-CLOCK",10)allocate(line,[in_stock_batch,shipment_batch])assertin_stock_batch.available_quantity==90assertshipment_batch.available_quantity==100deftest_prefers_earlier_batches():earliest=Batch("speedy-batch","MINIMALIST-SPOON",100,eta=today)medium=Batch("normal-batch","MINIMALIST-SPOON",100,eta=tomorrow)latest=Batch("slow-batch","MINIMALIST-SPOON",100,eta=later)line=OrderLine("order1","MINIMALIST-SPOON",10)allocate(line,[medium,earliest,latest])assertearliest.available_quantity==90assertmedium.available_quantity==100assertlatest.available_quantity==100deftest_returns_allocated_batch_ref():in_stock_batch=Batch("in-stock-batch-ref","HIGHBROW-POSTER",100,eta=None)shipment_batch=Batch("shipment-batch-ref","HIGHBROW-POSTER",100,eta=tomorrow)line=OrderLine("oref","HIGHBROW-POSTER",10)allocation=allocate(line,[in_stock_batch,shipment_batch])assertallocation==in_stock_batch.reference

And our service might look like this:

A standalone function for our domain service (model.py)

defallocate(line:OrderLine,batches:List[Batch])->str:batch=next(bforbinsorted(batches)ifb.can_allocate(line))batch.allocate(line)returnbatch.reference

Python’s Magic Methods Let Us Use Our Models with Idiomatic Python

You may or may not like the use of next() in the preceding code, but we’re pretty

sure you’ll agree that being able to use sorted() on our list of

batches is nice, idiomatic Python.

To make it work, we implement __gt__ on our domain model:

Magic methods can express domain semantics (model.py)

classBatch:...def__gt__(self,other):ifself.etaisNone:returnFalseifother.etaisNone:returnTruereturnself.eta>other.eta

That’s lovely.

Exceptions Can Express Domain Concepts Too

We have one final concept to cover: exceptions can be used to express domain concepts too. In our conversations with domain experts, we’ve learned about the possibility that an order cannot be allocated because we are out of stock, and we can capture that by using a domain exception:

Testing out-of-stock exception (test_allocate.py)

deftest_raises_out_of_stock_exception_if_cannot_allocate():batch=Batch('batch1','SMALL-FORK',10,eta=today)allocate(OrderLine('order1','SMALL-FORK',10),[batch])withpytest.raises(OutOfStock,match='SMALL-FORK'):allocate(OrderLine('order2','SMALL-FORK',1),[batch])

We won’t bore you too much with the implementation, but the main thing to note is that we take care in naming our exceptions in the ubiquitous language, just as we do our entities, value objects, and services:

Raising a domain exception (model.py)

classOutOfStock(Exception):passdefallocate(line:OrderLine,batches:List[Batch])->str:try:batch=next(...exceptStopIteration:raiseOutOfStock(f'Out of stock for sku {line.sku}')

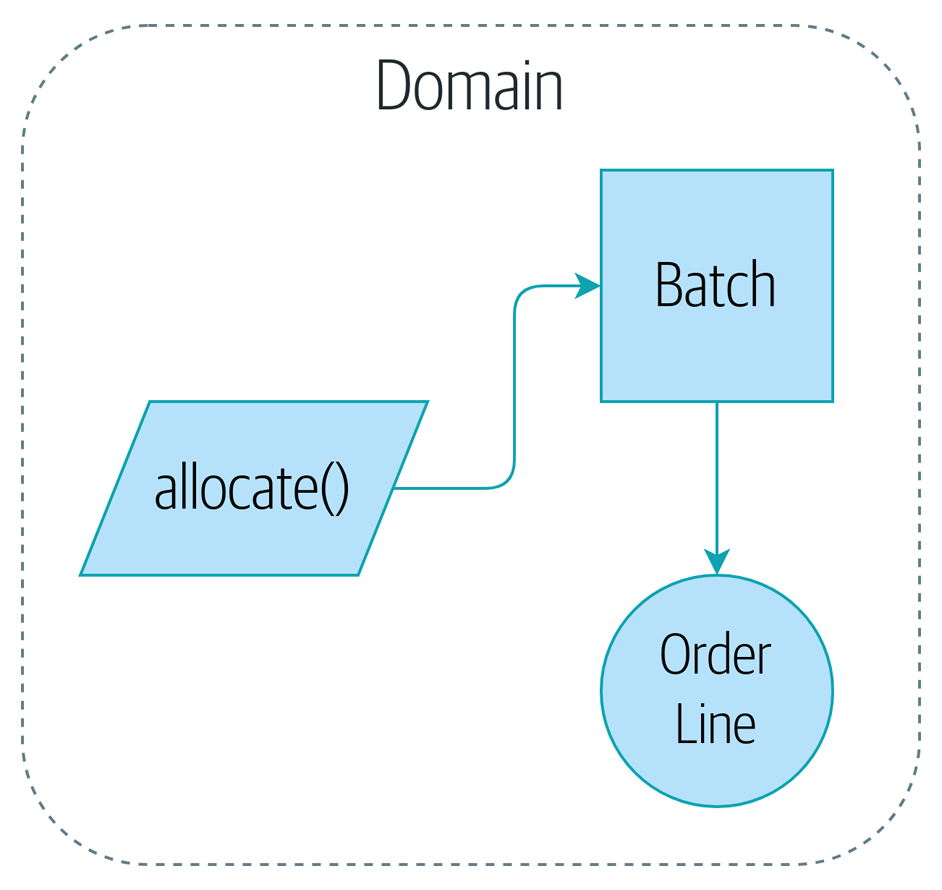

Figure 1-4 is a visual representation of where we’ve ended up.

Figure 1-4. Our domain model at the end of the chapter

That’ll probably do for now! We have a domain service that we can use for our first use case. But first we’ll need a database…

1 DDD did not originate domain modeling. Eric Evans refers to the 2002 book Object Design by Rebecca Wirfs-Brock and Alan McKean (Addison-Wesley Professional), which introduced responsibility-driven design, of which DDD is a special case dealing with the domain. But even that is too late, and OO enthusiasts will tell you to look further back to Ivar Jacobson and Grady Booch; the term has been around since the mid-1980s.

2 In previous Python versions, we might have used a namedtuple. You could also check out Hynek Schlawack’s excellent attrs.

3 Or perhaps you think there’s not enough code? What about some sort of check that the SKU in the OrderLine matches Batch.sku? We saved some thoughts on validation for Appendix E.

4 It is appalling. Please, please don’t do this. —Harry

5 The __eq__ method is pronounced “dunder-EQ.” By some, at least.

6 Domain services are not the same thing as the services from the service layer, although they are often closely related. A domain service represents a business concept or process, whereas a service-layer service represents a use case for your application. Often the service layer will call a domain service.

Get Architecture Patterns with Python now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.