1

A Maturing Industry

To improve is to change; to be perfect is to change often.

WINSTON CHURCHILL

HISTORICALLY, DESIGNERS HAVE BEEN relegated to the business of making pretty pictures. Most of us transitioned into user experience design, or as is more commonly known, UX, from other areas. But now that UX is everywhere, we are thrust into the limelight of product development with our own ideas forming a critical piece of the puzzle. It’s what we’ve always wanted! The problem? We’re not used to having to explain ourselves to other people, especially nondesigners.

As we look at how to talk about design to nondesigners, I want to first provide the context to help us understand how we got here in the first place. My own career has been littered with experiences (good and bad) of articulating design decisions to stakeholders. Those experiences shaped my understanding of design and helped me to see the importance of communication in the process. In addition, the term “UX” hasn’t been around that long. It’s important to know how the evolution of this term affects our ability to talk about our work with others. Of critical importance, however, is the shift that’s taken place in organizations from seeing design as merely a utility to being a fully engaged partner in the product development cycle. Similarly, web and mobile interfaces have transitioned from being only platforms for products to being the product themselves. All of these factors greatly influence design within companies, teams, and the minds of our stakeholders. So, let’s jump right in by first going all the way back to the 1990s.

Talking My Way Into Design

My path to working in UX began in marketing. I studied business for my undergraduate degree and quickly realized how powerful design was to bringing products to life. During college, every class project needed something designed. Local bands needed posters and album artwork. Friends needed simple websites. So, despite the fact that I wasn’t in the art department at my school, I had access to the tools (computers and software) for creating products and began my journey there, self-taught.

It was easy to get freelance work as a designer. It seemed like everyone needed a graphic or web designer, and so I did what I could to pay my way through college doing something I loved. One year, I worked part-time doing web design for a small record label. In my senior year, I was working full time at an electronic payment services company as the “Marketing Coordinator,” although most of my time was spent designing print ads and the company website. By the time I graduated, I had a decent portfolio of design work and was ready to take on the world.

I know it sounds crazy, but I really enjoy interviewing for jobs. I applied for just about anything and I said yes to every interview. It was a low-risk opportunity to practice talking about my work. Sometimes, I would go to interviews for jobs that I knew I didn’t want. Why? I enjoyed learning how to talk to people in those kinds of meetings and built up a vocabulary for discussing design with others. Once, I actually negotiated a salary for a web design job that I had no intention of accepting, simply because I wanted to see if I could get the manager to offer me a higher salary. He didn’t (in fact, he laughed at me), but it was exciting for me to push those boundaries and see just how skillful I could be at convincing him that I was worth it.

More than anything, I loved to talk with people about my work. I loved watching people look through my portfolio, comment on what they liked, or ask me questions about why I did what I did. I got a rush from telling other people about my design decisions back then; I still do today. I love to talk about design.

After graduation, I was asked to interview for a job as the creative manager at an electronic payment services provider, the same industry I had worked in earlier. The role required me to lead the “design department,” although at that time there was only one full-time web designer and a handful of freelance contractors. It was a dream job for a college graduate and of course I accepted the interview if for no other reason than curiosity. If nothing else, it would be great to show someone my work and talk about design.

I passed the first interview with someone from HR who wouldn’t really know whether I was qualified or not. She was just a gatekeeper. I passed the technical interview because I knew how to use design software and could easily show my skills. I passed the third interview with the director of marketing because she liked my portfolio and I was good at talking about it. So far so good! By this point, I had a lot of confidence. There I was: fresh out of college, interviewing for a manager role at a decent-sized company, doing the thing that I loved so much. I probably thought I knew a lot about design.

My last interview was with the vice president of marketing. She was a short woman who wore her hair in a bun. She had come from Proctor & Gamble and had a reputation for doing some great work. Her style was terse and to the point. She was smart and quick to reply. This woman did not mess around. In fact, you probably didn’t want to mess with her at all. It was a little intimidating, but having passed all the other tests, I thought I had nothing to fear.

She quizzed me on my portfolio, which I easily defended. She asked me about my past experience and ran through my resume, which I gladly bragged about. But then she got down to the point. She made a transition from interviewer to client and asked me the most memorable question of my career: “Let’s say I have a new project for you. What’s the first thing you would ask me about it?”

Having done freelance work and been on plenty of projects at my other jobs, it was an easy answer. How many times had I been in a similar situation with my other clients? I only had limited experience, but this was perhaps the most common meeting for a designer: the meeting with a stakeholder. Without hesitating, I began what felt like was a tried-and-true approach to all my previous work: “Is this a print piece or a website? Will there be color or no? Will we use stock photography or original? How many pages would the website or brochure have? And, finally, what is your timeline? When do you need it done?”

“You’re wrong,” she said. “None of that really matters. The most important thing you could ask me...the very first thing you should always ask is, ‘What are we trying to communicate?’”

I was stumped. Silent. Not only did I know that she was right, but she had exposed my superficial design ego in a way that made me feel small and completely clueless about the thing that I was most confident in—my ability to talk about design.

The good news is I got that job, and I’ve had many other jobs since then, but I never forgot that mistake. I was not astute enough to recognize that my stakeholder had a different agenda than my own. I failed to understand what she needed or to address her concerns. To her, the project was about communication. To me, it was only about pixels. In that moment, I realized that my ability to talk to other people about design went far beyond my own ambitions. I had to take into consideration the needs of my audience. My designs had to do something for the client. They had to solve a problem. And if I couldn’t communicate that, I was bound to be wrong again. For me to be successful as a designer, I had to figure out how to communicate to my clients what my designs did. I had to answer their questions in a way that made sense to them, not me. I had to express to them the rationale behind a design using words that would appeal to them and meet their needs.

If I could do that, I thought, I would be successful.

UX Is Still Young

To understand the problems we face when communicating to stakeholders, it’s important to take a quick look back at how we got here in the first place. We haven’t always been called “user experience designers,” whatever that means. It’s a new term that has evolved in meaning over the past decade and continues to evolve even now. I won’t address the differences between UX, UXD, UI, IA, IxD, or any other niche player in the product development life cycle. It’s my opinion that these designations are a luxury that, although valuable, have potential to confuse people with unnecessary complexity. The point is this: user experience design is a relatively new thing and we’re all continually adjusting to the changing attitudes and approaches to creating great stuff. It’s all design. When it comes to titles, no one really knows what they’re talking about. Right or wrong, we’re all just making stuff up and calling it “UX” along the way. Of course, this wouldn’t be a big deal if we designers were the only ones involved, but we’re not. Our stakeholders are equally confused by the terminology, and it’s not their fault.

IT’S A NEW WORD

As far as I can tell, the term “user experience design” emerged in the 90s as a branch of human-computer interaction (HCI), information architecture (IA) and other software-design disciplines revolving around the practice of usability. The term itself is frequently credited to Don Norman.1 Although the ideas and influences for UX have been around since the 1950s in Henry Dreyfuss’ “Designing for People,”2 it was not until Apple released the first iPod and then the first iPhone in 20073 that the term came into widespread use as the role of a designer who is creating the entire end-to-end experience using a user-centered design philosophy.

Since then, jobs for UX have been growing at astounding rates. From 2008 to 2013, the number of job titles including “UX” on Linked In jumped from only 159 to 3,509, growing by a factor of 22 in just 5 years.4 Computer World says that recruiters specializing in digital products are seeing a similar trend, reporting massive increases in the demand for UX Designers.5 UX Designer is one of the top jobs projected for growth through 2020.6 Through a series of market changes driven by rapidly evolving technology, user experience design seems to have come out of nowhere leaving both designers and stakeholders scratching their heads about the best ways of working together.

Schools are responding to the changing demand for designers by offering courses in information architecture, interface design, and usability testing techniques, and rightly so. But, the majority of people working in UX today didn’t come from a school that specialized in the field nor did we take a class to teach us a user-centered approach. We migrated into UX from other areas within the company: marketing, IT, design, research. Even human behaviorists and psychologists are finding their relevance in the explosive field called UX.

IT’S A NEW ROLE

In my experience, a typical UX designer’s story might sound like this: “I went to art school and started working as a graphic designer making marketing materials—brochures, print ads, and logos. Eventually, I started making websites, too. I even learned how to write some HTML and CSS. Soon, I found myself designing more websites and apps than anything else. Now I’m a UX designer.”

You might have entered UX from the development side with a highly technical engineering background. Maybe you didn’t go to art school, but started in business or psychology. Whatever your path, a lot of us UXers have similar stories. Most of us didn’t start out in UX, because UX didn’t exist.

By the time “Web 2.0” was popularized, designers had their first real opportunity to create applications instead of just brochure websites. The functionality and interaction that was once limited to desktop software was now possible and more easily available in the browser and to a much wider population of digital designers. With the advent of the iPhone, more companies began demanding better experiences and, in fact, needed experiences specifically tailored to these new devices.

Thanks to Apple, everyone began expecting everything to be well-designed. Suddenly, the demand for designers who knew how to create great experiences exploded. As design-centric social media skyrocketed, too, designers were able to create just about any interface they could think of and share it with the world. It was the democratization of design tools coupled with a free platform for sharing ideas. Almost overnight, the web designer had been transformed into a cacophony of acronyms that almost all boil down to creating the user experience.

IT’S A NEW TEAM

The awkwardness of UX’s adolescence could not be any clearer than it is in our relationships and interactions with developers.

Depending on the business, the website may have been born in the IT department. The engineering-types helped to build, support, and maintain it. They’ve been on a similar journey. Originally, the website was just a thing, but now the website has become the thing. Previously, the website didn’t need to connect to the backend, but now the website is the primary interface for the backend; the system was rarely exposed to the general public, now exposing the system to the public is a given.

The good news is that developers are used to helping the business solve problems with technology. They’re the ones who help the help desk. They know what the common complaints are among users. They maintain the backlog of issues and bugs that need to be fixed. Do users not understand that they need to create a complex password with a combination of characters and numbers? Just add messaging that lists all the password requirements. Developers have been solving these problems far longer than designers.

The difference is that the interface they used previously for solving these problems never mattered much. As long as you could teach someone how to use it, it was good enough. We didn’t need effective design, we needed documentation and training. The answer to a design problem was to educate the user. If we can help users understand the system, then they will know how to use it.

Over time, developers, too, have come to see the value of creating a great user experience. They understand that better design can result in a better application, both for them to build and for the business. They’re on board to help us create the best possible experience, but they probably have different ideas about how to do it.

There is an entire ecosystem of custom-built applications with terrible interfaces that companies must support with an army of developers and training staff. Designers are now being asked to redesign these applications, work with the developers entrenched in legacy systems, and create a better product. Everyone wants it, but getting there isn’t easy.

IT’S A NEW CHALLENGE

We have a design industry full of people with backgrounds that are vastly different than their current job titles. Artists, researchers, and recovering marketers are all doing the best they can in this changing scenery. The graphic or web designer as we knew it has been almost completely replaced by “UX.”

Now, companies are adjusting to their changing needs in a highly competitive marketplace because great design is the expected norm. For a lot of corporate history, design was just a utility. We used to only hire designers to make our stuff look more professional, to be sure the brand was consistent, or to communicate a creative idea. Now, we hire designers because there are difficult problems that must be solved in order for our products to be successful in the marketplace. Designers today are at the center of the product development cycle in a way that previously was not thought to be necessary. More people in the organization than ever before see the value in designing a great user experience. Sometimes, that’s the only way to differentiate yourself in a crowded market, and it makes an impact on your bottom line.

What happens when you take an industry full of creative, right-brained thinkers and thrust them into the middle of a product cycle with usability problems and business goals? Well, it’s no surprise that there is a disconnect between what the other stakeholders want to do and what the designer has so carefully crafted.

This book sits at the intersection of the growing UX design industry and the digital product business, where designers transitioning from making pretty pictures to creating great user experiences meet with developers, managers, and executives whose agenda and perspective may, at times, be at odds. The growth of the UX designer has changed our role in so many ways, none more so than the need to explain ourselves to other people who don’t share our experience in design.

Design Is Subjective...Sort of

When I interview designers, I always ask them, “What makes a good design good?” Most of the answers are predictable, and some of them are sort of right, but they all tend to sound something like this: “a good use of space,” “simplicity,” or one of my favorites, “when you can’t remove anything else.” Those are good things and they express how a lot of people approach design, but they aren’t truly what make a design good in the eyes of a business. They all speak to subjectivity—to an aesthetic that not everyone will agree on.

I’m not exactly sure where these designers come up with definitions that sound like something straight out of a Jonathan Ive memoir. I don’t think they learned it in art school. What concerns me is that I think they picked these catch phrases up from a social-media design phenomenon where “UX” means “something that looks as cool as an iPhone.” They’ve adopted it from a Dribbble7 mentality that suggests pretty things are the same as usability. It’s the same culture that causes well-intentioned designers to create a “redesign” mockup of any popular website or app without any clue as to what that business’ needs are. It’s less about solving problems and more about popularity.

The truth is, all design is subjective. What one person likes, another person hates. What seems obvious to me might not be obvious to you. What works in one context could fail miserably in another. This is why design is such a difficult thing to talk about, especially with people who aren’t designers. There is little common understanding of what design is or should be.

UX has come a long way in this regard. People understand that our decisions need to be founded in some sort of explainable logic. We are much better at using research to support our ideas so that we remove some of the subjectivity from the equation. That’s a good shift, but even research can be biased, unintentionally flawed, or otherwise inconclusive. This adds complexity to the challenge of talking about design and UX.

Businesses Don’t Critique

One of the valuable things about art school is learning to critique someone else’s work and to receive critique from others. When everything is subjective, it’s healthy to analyze one’s work in an environment where everyone is on the same intellectual page, as far as the subject goes. It’s beneficial for two people who share the same vocabulary to discuss their work and make each other better. This is a great skill for every designer to have, and it will go a long way toward helping you be articulate with stakeholders.

The shortcoming of the critique in business is that it doesn’t always help us address the needs of the business with our design solutions. With a fine art critique, invoking dialog is the goal. Two people can disagree and go their separate ways. “I see your point about how the red swaths in this landscape are reminiscent of the Dedocian period, but they’re actually intended to communicate the flushed faces of the people through Theochronic symbolism.” End of story. No more discussion. Agree to disagree. Even in schools that bring in volunteer “clients” or design imaginary products, the problems being solved have no real long-term effect. But, when the user experience of a company’s product is in question, millions of dollars in revenue could be on the line. We can’t simply go our separate ways. We have to find a way to talk about it and arrive at a final decision.

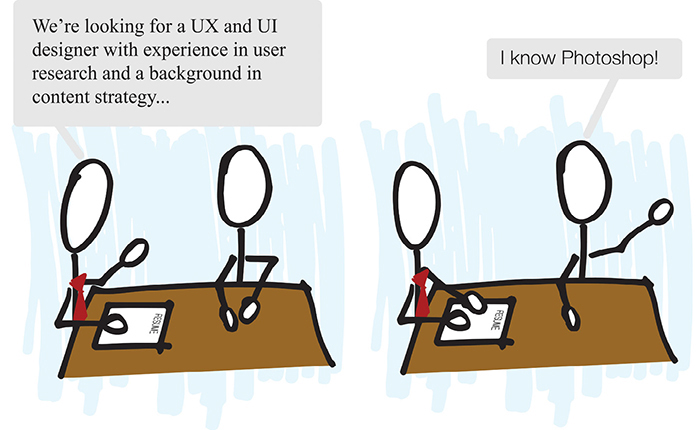

Further, when two designers are critiquing each other’s work, they are using a shared background and vocabulary that helps them to communicate. However, it’s not like that when you’re talking about design to stakeholders. Designers will discuss which UI control is right for this context. They’ll debate button styles. They compare their mockups to the user flows that were defined at the beginning of the project. We talk a lot about designs: the use, the form, the function, and we fundamentally understand how to solve our company’s problems with design but we lack the ability to explain that understanding to people who don’t share our background in design. We have yet to truly master the art of explaining these things to nondesigners.

So, even though it’s valuable and necessary for teams to push one another on their work, it’s not what will ultimately make a difference in the final decision for our project. It’s just family chatter, an internal conversation for an in-group of designer-types. It’s not at all the same as talking to someone who doesn’t have the same level of interest in design. It’s not necessarily the right way to talk to a nondesigner.

Ego and Intuition

In some ways, there is an arrogance that prevents us from being truly productive with people outside of our own peers. We don’t always see the other stakeholders on our project as knowing anything valuable about design. We don’t trust their instincts the way we trust our own. After all, we’re the experts. We were hired to design things because that’s what we’re good at doing. Why should managers care? Can’t they just trust us to do our jobs?

Designers make a lot of decisions based purely on intuition. In fact, our intuition is really good at solving design problems in an elegant and simple way. We’re wired to think visually, to organize elements logically for the user, and to pay careful attention to the details. The problem is that because design is subjective and because we don’t always understand how our intuition connects to the problem at hand, we’re unable to adequately tell other people why we did what we did, and that’s one of our biggest failures.

It’s as if our brains go on autopilot when it comes to making design decisions. It’s muscle memory. A dancer might have a difficult time describing how she moves because she has done it so much that she just knows how to do it. She doesn’t think about it, she just does it. Likewise, we tend to create things that we just know to be the right solution; perhaps it is our preference, maybe it’s based on experience, or maybe it was unconsciously picked up from observing users. Whatever the reason, when someone is good at what they do, they have a hard time telling people why they did what they did. They don’t think; they just do.

To make matters worse, we may be the only people in the room without a specific, articulated justification for our choices. Developers make choices based on what’s possible or how to maximize their time and code. Executives want to do what is going to make the company the most money, and so they propose things that they think will accomplish that. Marketing wants you to make changes so that everything is consistent and on-brand. But, unless you’re prepared to defend your decisions intelligently, the only thing you can say is that you disagree. That degree of subjectivity has to change.

A Shift Toward Products

A designer, a developer, and a CEO walk into a bar—three different bars, on opposite sides of town. The designer orders a pale ale with an oaky flavor and a hint of citrus. The developer asks for his favorite beer on tap. The CEO goes for the day’s special but without too much foam, in a cold-frosted mug, and with a glass of water.

They all drink the same beer.

ATTITUDES HAVE CHANGED

To understand how designers fit into corporate culture, we need to understand the changing shift and attitudes toward design as something more than just an aesthetic. When our job was to make the company look good, it didn’t matter as much who got their way on the final design. Now that we’re solving problems that affect the bottom line, everyone has an opinion on the best way to solve it.

When the web took over everything, organizations, large and small, were on a much more level playing field in terms of reaching their audience. Everyone wanted and needed a website, designers hurried to meet the need, learned basic skills, and began pumping out websites to meet demand. For the first time, the world of HCI and interface design that started in the tech companies of Silicon Valley was available to a much wider group of creators who had no idea what they were doing. That’s how the majority of the web was built.

THE WEB HAS CHANGED

All organizations embraced the web because it was an inexpensive mass medium, first, for communicating your message, then for selling your product, and now for actually being the product itself. This evolution caused a shift in how organizations think about design.

When designers were only communicating messages, companies didn’t need to micromanage a design process that was just meant to make the company look good. Executives were typically happy if the website didn’t look like crap, or at least that it looked better than their competitors. But for the most part, design was this other thing, over there, off in the corner. It was nice to have, we liked it, but we didn’t need to get involved much.

As the web shifted and made it possible for us to sell our products, the focus was still on aesthetic with the addition of utility. As long as the website worked, management didn’t need to care too much about the details. Something just needed to exist and get the job done. “We need filters. Those are the filters there? Great! We need an ‘Add to Cart’ button somewhere—I don’t care what the color is; what difference does that make?” And in this world, as long as the stakeholders knew where to find the thing they thought was important, that was all that mattered. We might even set goals for the website or hire a salesperson to monitor and grow our “eBusiness,” but it was less about strong opinions and more about getting the job done.

In the past 10 years, there has been a dramatic shift in attitudes toward what the web and web-like interfaces (like native mobile apps) represent. You know the story about the explosive growth of social media, the proliferation of native and web apps, and the proclivity of people to carry these things around in their pockets to be constantly engaged, consuming whatever the next thing is. Researchers believe web revenue will continue to climb as a percentage of overall retail,8 and that as much as 60 percent of all retail transactions will involve the web in some way in coming years.9 Mobile revenue has crossed the 50 percent mark for many of the largest companies,10 what Luke Wroblewski calls their “mobile moment.”11 The most successful business stories nowadays are of companies who created a product that was focused on the design.12 Heck, there is even a movie13 and book14 about how design is changing the business world! Great design has taken center stage as an asset, a competitive advantage, and a must-have in order to survive in the market.

BUSINESSES HAVE CHANGED

Closely aligned with the growth of the web to serve products and experiences is a new business approach in which entire organizations arrange themselves to value design and make it a part of their core culture. As startups and big corporation CEOs are beginning to value design, we see an organizational model that makes it possible for businesses to really hone in on and make product design their primary strength. To complicate matters, businesses are quick to adopt buzzwords, especially those that seem to help them solve a problem they see in their organization. An executive might read an article about a successful business that has a design-centered product approach. The quote from the “user experience designer” is the tipping point. Maybe that’s what he needs! His web designer now has a new title. This is why UX continues to be misunderstood, even by the designers doing the work. Businesses are changing to adapt to this new reality, but none talk about UX in the same way.

As a result, you have designers who started out somewhere else, creating stuff that was mostly focused on the look and feel. And then you have managers and executives who cared more about the utility and function of their thing—but more and more these two primary players are moving toward each other in a way that has incredible potential to change their organizations for the better. Executives now realize just how important design is, and they want to influence the process because their business is on the line. Likewise, designers have come to understand the value of creating an experience that is based on solving problems and backed up by research. And the two meet in the middle, in a meeting.

That’s where we find ourselves today. In a meeting with people who have no idea how to do our jobs, yet consistently find it their place to tell us how to do it. It’s enough to drive any designer insane.

Digital Experiences Are Real Life

The organizational transition to understanding and valuing the UX of digital products is maturing. From these original attitudes and approaches to design comes a mutual understanding that a great user experience will create a great product. A great product will sell, be easier to support and maintain, and be good for the bottom line. These historical attitudes—the stereotypical personality types that create these roles in the organization—all come together for a single purpose: to create the best possible products. The way that we now realize we can create the best possible products is through design. The problem is that only one of these players is a designer.

But why does this matter? If we are the experts, why should we have to justify our decisions to nondesigners? The reason is that UX has gone “mainstream,” in the organization and even within pop culture. The most popular and interesting companies have put design at the fore-front of their product offering, creating a buzz culture that drools over every new release and a fan following that promotes their brand for them. I’m not only thinking of Apple, but also brands such as IKEA, innovators like Tesla, and unique problem-solving designs from Dyson, Segway, or Nest. These brands command respect, elicit strong opinions, and foster loyalty from the people who follow them.

SOCIAL MEDIA HAS CHANGED HOW PEOPLE VIEW DIGITAL PRODUCTS

It’s not only physical products that have transformed our understanding of the value of UX within the organization. Regular “websites” have proven that UX is a critical component to a company’s success. Millions of people use Facebook every single day. Each minor tweak to the UI or change to the design incurs the praise or wrath of every user. Why? Because Facebook (and other services like it) is a very personal part of our lives. Never before have we had a platform for sharing the most intimate and mundane details of our everyday lives. For many, social media is their window into the world. It is the lens they use to connect and communicate with their friends and family. It’s a powerful social engine that frames every modern conversation. And so it’s no surprise that the details of how the interface works elicits strong reactions from people who perceive it almost as an intrusion into the way they live their lives. For the first time, people who previously barely noticed the design of their favorite website now are obsessed with the smallest interface details of other apps. They notice them, they touch them, they interact with them, and those elements become part of their lives. Changing those things means changing the way people interact with the world. This is why so many people have an opinion about your work.

POLITICS HAS CHANGED HOW PEOPLE VIEW DIGITAL PRODUCTS

Also notable was the reaction to the failures of the 2013 launch of the healthcare.gov site in the United States. Usability was a core factor in the demise of that initial launch. But why did that matter to people? If the website “worked,” why did it matter if it worked well? For the same reasons as social media, the healthcare website was an intensely personal, deeply intrusive interface that threatened to change the way people lived their lives. I might argue that even the best UX might have still resulted in failure if for no other reason than the sociological implications that a “designed system” was representative of the massive changes facing the American people. An interface was responsible for people’s private healthcare. Changing the way people managed their healthcare meant changing their perception of their health. But the point is this: the president of the United States was talking about usability in public forums to a mass audience!15 It’s no wonder that UX has become a central focus of many organizations.

To take it a step further, we don’t have to look far to see how digital products have fueled uprisings and revolutions in places such as Syria, Turkey, Egypt, and even Ferguson, Missouri in the United States. In these situations, the use of digital products became the voice of the people and upset the political balance. An interface designed by someone in a meeting with stakeholders became a tool for empowering an entire population toward revolution. This is why so many people have an opinion about your work.

PERSONAL DEVICES HAVE CHANGED HOW PEOPLE VIEW DIGITAL PRODUCTS

Perhaps the biggest factor, though, in the explosive growth of UX as a discipline is the personalization and shrinking of the devices we use to interact with the world on a daily basis. Sitting at a computer is not a terribly personal experience. It is a separate device at arm’s length, with physical controls that one must learn to manipulate. The input methods are indirect: what I do down there with the mouse changes what I see up here on the display. And at the end of the day, I have to put my computer away and move on with my life. Something as simple as looking up the weather on a computer must be done purposefully and intentionally.

As mobile phone growth turned powerful smartphones into touch-screen super phones, our ability to interact with products and services on a regular basis shifted from being an intentional, arm’s-length, conscious choice to an automatic muscle-memory involuntary jerk of the wrist. Like social media, our devices are intensely personal and are becoming more intimate. Our interface with the world is no longer the machine at arm’s length. It’s the touchable glossy display that we always have with us. Always on, always connected, always shaping the way we see our world. As a result, universal understanding of the importance of UX has grown, too. Every software update introduces new ideas and elicits strong opinions from every user. This is why so many people have an opinion about your work.

STARTUP CULTURE HAS CHANGED HOW PEOPLE VIEW DIGITAL PRODUCTS

Today, businesses and even entire industries are built around the “disruption” of creating a better user experience. The way that you succeed in business is to find an existing category and then tweak the user experience to the nth degree. It’s not necessarily about being original, but about being the best—and design is usually the great differentiator.

The most prominent example I can think of is Uber. The entire business is built on creating a better end-to-end experience for taking a cab. A simple task with incredible implications for improving the user experience, Uber did what any good “disrupter” should do: it looked at the process of taking a cab, broke it down, and solved all the problems with better design. No one likes standing on the street and waving their arms? Fixed. Actually, no one likes waiting out in the rain either. Fine, stay inside. Cabs aren’t clean or reliable? Uber guarantees that they are. Payment and tipping annoying? They fixed it. Want to provide feedback? It’s baked in. The entire process of getting a cab has been upended by one company that looked at the problem and found design solutions to everything. This is why so many people have an opinion about your work.

THIS IS WHY SO MANY PEOPLE HAVE AN OPINION ABOUT YOUR WORK

Our entire culture has shifted its thinking about design, specifically the design of interfaces, devices, services, and products. Everyone has a personal device now, and they are only getting more personal. The Internet of Things will continue to push UX into (and onto) our faces at every turn. Everyone has apps they use, love, and hate. The people in your meetings are probably participating in another user experience while at the same time reviewing and considering your own. It’s no wonder that everyone everywhere at every level of the organization is intensely interested in and has an opinion about the UX that you are trying to create. How are you going to deal with it?

As a result, more people than ever before are interested and involved in the design of your product. What was once relegated to the “Oh, that’s nice” category of insignificance is now the center of everyone’s attention. People from all over the organization see the value of creating a great user experience and they all want to participate in the process. Marketing, executives, developers, customer service, even people in accounting will want to tell you how they think it should work. People are excited about UX because they recognize the long-term effect it has on the product, the business, and the bottom line. The good news? You’re a very popular person!

Get Articulating Design Decisions now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.