Wikipedia, itself a product of crowdsourcing, defines marketing as the process of communicating the value of a product or service to (potential) customers for the purpose of selling that product or service.[13] Like a shiny new sports car in a dealership full of sedans, marketing has always been the sexiest and most visible application of big data and social media analytics, and also its greatest source of hype; tap in to the Twitterverse or make your latest video “go viral,” so they say, and your product or service will hit the revenue jackpot.

Marketing was not the first place where data analytics was put to use. That honor goes to the finance industry, which invested heavily in big data analytics methods for high-speed trading over stock performance. Through the onset of online commerce and social media, however, big data ultimately entered the marketing area, sometimes with stunning success, but only sometimes. It comes as no surprise that social media outreach or social media listening is one of the top strategies to optimize marketing.[14] Today there is a certain degree of hype about using social media within marketing. You may be reading this book for that very reason. There is an implicit promise with social media that it will help people succeed in marketing their products and services. But how to measure its impact? Moreover, with social media marketing, we have created more data and more measurements. Can we find here the fourth “V” of data?

Disentangling the effects of selection and influence is one of social sciences greatest unsolved puzzles[15]

The short answer to this is that appropriate metrics are the key to using big data and social media effectively in marketing. This chapter will explore various measurements in social media marketing. Using these metrics, we will uncover a few of the myths surrounding social media marketing on one hand, and hopefully sharpen your eyes in looking for the right metrics for your business on the other.

This promise of social media and social media analytics often lies in viral success stories about products or services. One such example is a case reported by McKinsey & Company: months before the US launch of its Fiesta subcompact, Ford Motor Company lent early models of these cars to 100 people recognized as social media “influencers” and asked them to share their observations online. YouTube videos related to this campaign generated over 6.5 million views, Ford received more than 50,000 requests for information, and when the car was finally released in the US, 10,000 were sold in the first six days alone.[16]

Scenarios like this play out all over the business world today. For example, at a recent conference discussing small business success, one participant after another took to the podium to describe how their businesses grew through social media, viral videos, an online community, and, well, you get the picture. And of course, you want to become one of these success stories. So, how do you use social media to succeed at marketing?

The good news is that for the right products, and at the right moment, social media data can drive both awareness and intent. In the case of the Ford Fiesta, for example, the awareness generated led to a successful launch. It was not only the outreach to social media influences that created this success, but also factors such as our natural attraction to automobiles, the existing brand recognition of Ford Motors manufacturer, and above all, a unique and captivating new product. However, as we will discuss later more in depth in Testing for Correlation, it will be difficult to bring proof that those initial car sales can be attributed to the social marketing buzz.

The use of social media can bring unique benefits to marketing campaigns. At the same time, the idealized view that many of its success stories present is not accurate. Thus, what can we measure realistically? This chapter explores three key aspects of social media in marketing:

How social media can build brand awareness through measurable quantities such as reach, click-through rates, and consumer engagement levels.

Which approaches to using social media can determine the intent to buy, leading to behavioral and social targeting.

Whether or not influencers—people who determine our actions and choices—exist, and if so, where to find them.

Brand awareness and intention to buy are the main two aspects of marketing. Said differently, marketing wants to create a desire for a product (make it known) and have customers act on it. Social media can drive both of those aspects effectively. Social media enables you to engage your consumers at a level beyond that of other traditional marketing channels, including giving you permission to connect with their own social media environment. Social media can also be the final trigger to buy.

An equally important focus of this chapter, however, is understanding and avoiding the hype that surrounds the use of social media in marketing. Social media is not as inexpensive or viral for most people as the war stories would have you believe. It is not a single, monolithic marketing channel, even though many people speak of it that way. And studies have shown that the concept of influencers who spread your brand message far and wide is often a myth. To succeed using social media, understanding its misconceptions is just as important as knowing its advantages.

Social media is still a young area that has undergone extremely rapid growth. For example, Facebook and the microblogging service Twitter date back only to 2004 and 2006, respectively, but as of 2013 boast 1.1 billion and 500 million users, respectively. The result is nothing short of a revolution in society that has unleashed a wealth of unstructured data and that, in turn, has drawn massive interest from data scientists. Our hope is to show you how to use social media in ways that are most likely to be effective in the real world of marketing. Is it worth the effort? How do you measure it? When and where should it be used?

The cartoon in Figure 1-1 shows the core conundrum of social media data in marketing: the often tenuous link between this data (such as this dearly departed person’s 2,000 Facebook friends), brand awareness (who paid attention to this person), and intent (in the form of attending his funeral). This chapter will explore both the possibilities and pitfalls of using this data to influence purchasing behavior. Let’s start by exploring some of the common myths behind the use of social media.

Social media seems like an ideal place to create awareness by brand advocacy, and many anecdotal success stories seem to serve as proof of this. The level of hype in many of these stories can be compared to the US gold rush in the mid-1800s, when claims of easy riches led many people to seek their fortunes in the American West. Most would-be miners ended up disappointed, and yet this movement ultimately spawned trade, commerce, and infrastructure, as well as a legitimate gold industry.

Today’s modern social media gold rush takes the form of people believing that they can become rich through viral videos, messages retweeted far and wide, and thousands of followers on Facebook. While few succeed in getting rich quick, they are all part of a legitimate social media infrastructure that is changing marketing for good. Before we look at how to leverage this infrastructure to build brand awareness and assess sales intent, it is important to understand the myths that still pervade social media. Here we will discuss three of the most misleading and prevailing ones encountered in marketing today.

The first myth about social media is that it is cheap. Please do not get fooled: it is not cheap anymore. Danny Brown (@DannyBrown), CEO of Bonsai Interactive, estimated in 2011 that the cost of a social media campaign is about $210,000 per year. That is not as expensive as a full traditional media campaign, but much more than the prevailing myth that social media provides free advertising.

We saw this kind of myth before at the dawn of television. Did you know that a TV advertisement could be as cheap as nine dollars? Yes, that was the cost of the first TV ad in 1941: a 10-second spot of a black and white map of the United States shown in prime time before a baseball game. (See Figure 1-2.)

In this ad, a voiceover simply says, “America Runs on Bulova Time.” The descendants of Joseph Bulova paid only nine dollars. No one would have imagined that they had just entered an industry that is now supposed to reach $214 billion by 2014.[17] As inexpensive as TV advertisements appeared to be at the beginning, social media campaigns seem to be cheap today.

But similar to the steady rise of TV advertising costs, we are starting to see a rise in the cost of social media advertisements. For example. the advertising tool developer TBG Digital noted that the average cost of a Facebook ad has increased by 62% over the course of just half a year. Social media advertising is no longer inexpensive.

Another similarity is the discussion on the effectiveness of the new medium. Similar to TV back then, social media is often doubted to be effective. How often have you heard that the return on investment (ROI) in social media is unproven? Bulova simply tried TV out and became successful. Social media advertisers are in a similar spot today.

The second myth about social media concerns speed. Again, driven by initial success, many managers believed that social media is fast. In 2004, social media was a new way to reach out to consumers, and the first marketeers to use it had the advantage that they only needed to put up a Facebook page and people would come to it almost by themselves.

Those times have changed. Today it is more and more clear that social media has value in the marketing mix; thus, more and more brands are using this channel. This means that it is harder than ever to be heard. Take Twitter as an example: in 2012, Twitter updates alone produced 8 billion words per day, more than twice the number of words[18] the New York Times produced during the last century. To make yourself heard in this space is now more often a slow process.

We say “more often” even though there are the shiny and sometimes scary exceptions. Within a few hours, issues, news, or ideas might spread like lightning within social media networks. They might, but they do not have to, and in most cases they actually will not. We will look at those situations more in Chapter 3 and see that it is hard, or even impossible, to plan such “viral” outbreaks.

The third myth is how people talk about social media as if it were one channel, just like television is one channel and print is another. However, this will lead to confusion once you try to design measurements for this so-called social media. A tweet using 140 characters to broadcast generic information has completely different goals and mechanics than, for example, a forum discussion or a YouTube video.

Social media is not one type of media, but rather a class of media with different mechanics and goals, and thus it needs very different kinds of measurements. Social media enables users to create, to engage, to share, or to play games; and for these purposes, many different technologies are used. For a business this means that it will not deal with one platform and five different measurements, but perhaps 10 different platforms and 70 different measurements that may appear similar but are hard to compare.

As a class of media, social media can be broken down into three distinct types:

- Earned

This is content about the brand shared or created by consumers themselves. In the early days, social media was only earned. A good example of this is product reviews on sites such as Amazon.com. For example, the first book in the Harry Potter series (The Sorcerer’s Stone) received close to 6,000 reviews by 2012. Why would someone bother to write the 6,001st post? Because customers want to share their excitement and tell it to the world. To share positive and negative moments is a human trait and often core to the existence of earned media.

- Paid

Most traditional marketing channels, such as television advertisements, are paid. While Amazon does not allow reviews to be bought, other social media channels allow so-called promoted articles. For example, Twitter offers promoted tweets; Facebook displays your status updates only to a limited percentage of your fans except when you pay additional fees for advertisements or so called featured stories; Stumble-Upon promotes your link with a so-called paid discovery, and so on. These are all effectively paid advertisements.

- Owned

Brand owners and companies can start their own blogs or fan pages and thus create “owned” content and accounts that they control, like their own YouTube channel, web page, or Twitter account. In this way, brands became publishing houses by themselves.

It is not always easy to see the differences between an owned and an earned Facebook page. While most brand pages on Facebook are owned pages, the most well-known exception to this is the Coca-Cola Facebook page. It was started by two enthusiasts, and Coca-Cola did not claim the page but gave the two founders a nice treat of a visit to Atlanta. Coca-Cola actively promoted this story through a video that went around the world.

In addition to these three types of social media, we can add a fourth dimension: sharing. How and whether data is shared creates a new dimension. Sharing is different across social media platforms, however. Sharing has one common trait: it is easy to do. There’s no need for long explanations or owned content. It should be as easy as the click of a mouse. However, no matter which of those four dimensions we analyze, not a single social media channel is the same; they follow different rules, and you will use different metrics to measure success. A good classification of social media is given by Kaplan and Haenlein,[19] who have described social media in terms of the following different platform categories:

Collaborative projects such as Wikipedia or Github

Content in blogs or microblogs such as Facebook, Qzone status updates, and Twitter and Seina Weibo Messages

Content communities such as YouTube and Tudou[20]

Social networking sites such as LinkedIn and Facebook

Virtual game worlds such as FarmVille and World of Warcraft

Virtual social worlds such as Second Life and SMEET

We would also include content curating (such as Digg, Pinterest, Scoop.it, and many more) as an additional category, as we believe that since its initial publication in 2010, this has become an independent social media activity with its own dynamics and own measurements. Thus it is easy to see that social media is not just another channel, but at least seven different types of channels.

This means that depending on how it is used, social media carries with it the potential to earn an audience, attract an audience through owned publishing activities, or serve as a channel of paid advertising. Each has different objectives and measurements, which interact with the inherent attraction of your products, your services, your marketing activities, and the reach of the platforms themselves to produce results we can measure.

Social media is often employed to create awareness and boost branding. How is this done? There is no one single answer.

The content and the medium need to be the “right” ones. Coca Cola, for example, suggests that its content should be “liquid and connected.”[21] For the Coca-Cola company, advertisements need to not only advertise but also to inform, amuse, and engage, along with many other objectives. However, what works for one company does not necessarily work for another. Very often the same marketing logic cannot be replicated for another product or target group. That is an issue from the data perspective. It is hard to learn from those cases as it is difficult to abstract from a given context. Thus in the near future we will not have the algorithm that tells us the right marketing message to write. Branding will always needs a high level of creativity together with the notion of finding the right tone to inspire your customers.

Thus content is still king and not the media channel as such. However, those who seek to use social media to make their messages “viral” are on a quest similar to that faced by the motion picture industry. Within the movie industry, any measurement that could help to improve or to better predict the performance of a film is worth millions of dollars. However, despite lots of focus groups, detailed studies, and the like, the bullet-proof formula for film production still fails to exist. Arthur S. De Vany describes this in his book Hollywood Economics: How Extreme Uncertainty Shapes the Film Industry (Routledge):

There is no formula. Outcomes cannot be predicted. There is no reason for management to get in the way of the creative process. Character, creativity and good story-telling trump everything else.

Despite an entire industry devoted to the viral use of social media, similar principles apply. There is no guarantee of virality,[22] nor does the ability exist to design for this using a smart metric. While a good branding message depends on creativity, and there are ways to measure when a branding effort has worked, the market ultimately decides what messages are worth spreading, just like with a hit movie.

Such measures need to answer the simple question: “How many can recall the brand?” It is important to remember that there is more than one type of social media, and not every social media type can measure this. As we discussed earlier, this is a broad and diverse class of media where each type will measure reach slightly differently, often requiring separate benchmarks. From there, the question remains of how to translate reach to awareness, and beyond to purchase intent, as we will explore.

Within each type of social media there are several underlying platforms offering different metrics. For example, let’s examine Twitter to show how difficult it can be to have a mutual understanding of reach.

Table 1-1 shows a selection of some metrics from different social media measurement companies on Tim O’Reilly’s Twitter account (@timoreilly).

Table 1-1. Tim’s measurement overview (as of May 2012)

| Company | Metric Name | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Twinangulate | Combined Reach | 120,310,807 |

| Klout | True Reach | 56,000 |

| Twitter Grader | Rank | 2,987 out of 10,997,926 |

| How Sociable | Magnitude | 4.4 out of 10 |

| Fisheye Analytics | Influence | High |

| Peer Index | Audience | 94 |

| Twitanalyzer | Effective Reach | 1,630,000 |

| Twitanalyzer | Potential Reach | 3,060,000 |

This table shows several different measures that can be summarized under “reach”; for example, his rank in the Twitterverse, his effective reach (i.e., his more than a million and a half followers), and his potential reach, as well as numerous quantitative measures of influence. Metrics such as these serve as examples of how you can quantify a social media footprint. However, it also shows that there is a whole range of metrics that all try to describe something similar. Thus, while numbers do not lie, each of these numbers tells at least a slightly different story.

Moreover, this example looks only at Twitter. Other media types such as Facebook or YouTube add a whole new list of reach metrics of their own. These may range from number of page views or video views to frequency of comments or “likes.”

While there are many different metrics for reach per social media type, none of them are well set to measure awareness by itself. While it is easy to reach many potential consumers with a sufficiently big media budget, it can be hard to make them remember the brand. Direct marketeers often try to build such awareness by employing a so-called trigger that will make the audience react, such as a phone number to call or a question to answer. Those actions will make the audience remember the brand more easily.

Social media now offers a bigger range of technical possibilities to trigger a reaction. The Ford example from the introduction to this chapter is already a highly elaborated one. More simple ones can be as easy as just clicking “like” or “retweet.” With one mouse click, consumers can much more easily react or engage with these channels versus traditional media, and their reactions can be measured. Here are some examples:

How many people clicked something? The biggest example here is click-through rate (CTR), which is well known from web analytics.

How many people redistributed a given article? This could mean that they tweeted, scooped, pinned, liked, or shared the article in any other form.

How many people engaged with a given article—replied, discussed, or reacted in any form?

How many people copied content or took the main idea from an article?

All of those actions can be classified as earned media. It is the customers who conduct them according to their free will and without control by the advertiser. Engagement is thus a very important metric for any marketeer, as there is a good correlation between the engagement and the created awareness.

Of course, there is a deeper issue beyond the connection between reach and awareness: awareness is not sales intent. While branding looks mainly to create awareness, an essential step is still missing. What constitutes the right purchase trigger? How can you make a person buy? We will look at this later in this chapter, when we discuss the issue of sales intent.

The next section looks at a successful example where social media was used in a branding campaign. It effectively uses all four dimensions of social media (earned, paid, and owned channels, across multiple platforms), and in the process merges social and traditional media around a common focus. Finally, it produces measurable results consistent with branding objectives. Let’s take a look at how this campaign was created and executed.

Social media offer a wide range of different engagement metrics, and it makes sense to combine those measurements in any awareness campaign. A brilliantly executed campaign in this respect was the case of Virgin Atlantic Airways’ “Where is Linda?” promotion.

In early 2011, Virgin Atlantic launched a $9.7 million global campaign starting with a fast-sequenced and flashy TV commercial.[23] The combination of the surreal pictures with good-looking people reminded one more of a promotion for a new James Bond film than of an airline advertisement, with the underlying song “Feeling Good” by Muse playing during most of the commercial. A the very end of the commercial, in the last five seconds, one of the flight attendants pointing at a girl in the sky asked in a colloquial tone, “Is that Linda?” This abruptly broke the overall atmosphere of the commercial and left the audience wondering, “Who is Linda?”

This hint in this video advertisement formed the start of a new Facebook campaign. It was a well-placed trigger for consumers to start their search for Linda. At a dedicated Facebook page from Linda, consumers could guess and find out where this imaginary flight attendant just flew to and win flights if they were correct.

This sweepstakes campaign was well received, and even years later Linda still gets friends on Facebook and receives comments on her wall. This campaign is a great example of awareness marketing done right. It used a combination of many media types, including social media and television, to create an overall awareness for the brand. Through the use of a dedicated Facebook page and a sweepstakes, Virgin Atlantic created a combination of owned, earned, and paid content, as discussed previously.

But was it a success? The answer is yes if its goal was to create brand awareness for Virgin among potential air travelers. An easy way to estimate brand awareness is to measure the engagement created. Wildfire Interactive, the company that helped create the campaign, later reported the following results:

By the end of the promotion period, the airline had received 15,449 sweepstakes entries and gained 8,282 “Likes” on its Facebook page! Additionally, Linda helped engage consumers in a new way: she gained over 1,900 friends during the promotion’s lifetime.

—Press release from Wildfire Interactive

For that time, those numbers of likes and friends made the campaign unquestionably successful, at least when one looks only at the interactions on Facebook. However, what about the ROI? The question is whether the campaign ultimately led to sales of more airline tickets on Virgin Atlantic Airways. Linking the cost of $9.7 million of the campaign to the number of engagements, you’d have a hard time calling this a success. A good measurement should not only look at the direct link to awareness and intent. A good measurement would need to look at incremental ticket sales compared to a time before the actual advertisement or compared to the previous year at the same time. Additionally, a good measurement would try to measure the longterm impact that an awareness campaign is intended to build.

The missing part to include, as well as the longterm effects on a ROI for Virgin, is the question of how can you convert these contacts on Facebook into sales later; in other words, how can we move from awareness to an intent or to a purchase?

There is no automatic process saying that because you “liked” Virgin on Facebook, you will fly Virgin next time. Thus, these contacts become like an email address in a distribution list, and their value very much depends on what Virgin does with these Facebook contacts over their lifetime. For example, the airline can offer them promotions; it can ask them for customer feedback to improve their service, and it can use them to spread its brand in word-of-mouth campaigns.

Thus to understand the value of the fans, one needs to analyze the following questions. Please note that one could phrase the same questions for Twitter or any other social media community tool instead of for Facebook by replacing the fans with the followers or other appropriate nomenclature:

How often, on average, can one reach out to the fans without losing them?

What is the average conversion rate on offers sent to the fans?

How many new fans will the current fans engage and thus grow the fan page?

The value of the branding campaign can only be answered if we say what we are going to do in the future with those contacts. Often, however, that is not yet clear because the tools and the medium are relatively new. With traditional email addresses, many marketing managers have a good feeling about what a good address should yield. But with a friend on Facebook, this value often is yet to be determined.

Companies usually first build a fan base on any social network so that the value of the fan base can be tested later once it is set up. Such testing is a highly relevant and important step. Often the expectations between what the company believes they want to do with the friends and what the customers expect from the company can be very different.

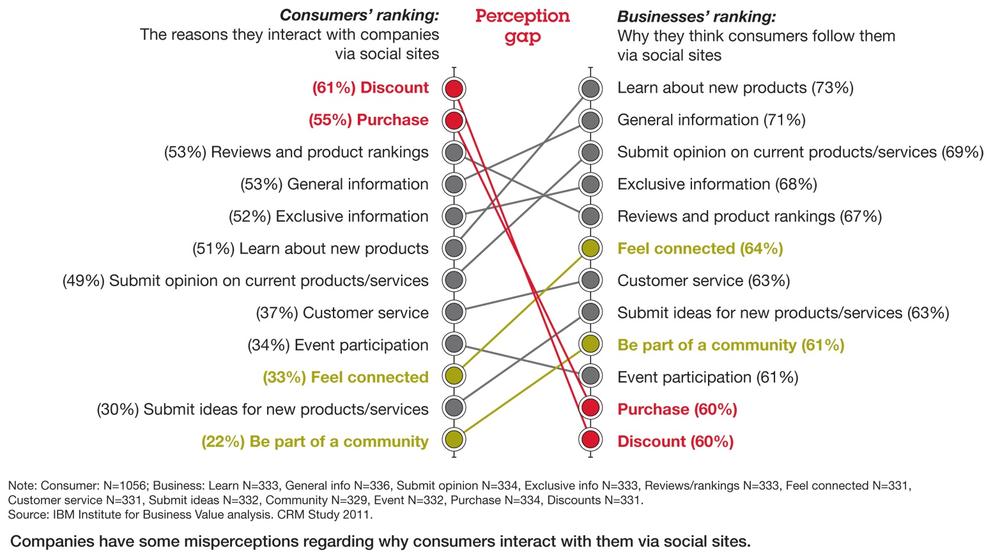

A 2011 study[25] by Carolyn Heller Baird (@cjhbaird) and Gautam Parasnis, for example, revealed that there are often differences between what consumers expect from interacting with a brand through a social network versus what companies hope they will gain from them. For consumers, the foremost reason to connect to a brand-centric social media site was to get a discount or to be able make a purchase. Meanwhile, business leaders thought the main reason for them to set up such a site was to educate the consumers about new products or give them general information. The ability to give a discount ranked last under all possible reasons (see Figure 1-3) for most businesses. This research shows very clearly an expectation gap that is independent of the actual platform used; therefore, it will be an issue no matter whether brands are using Facebook, Twitter, Quora, or any other community building platform. In building a brand-centric community within a social network, businesses will need to proceed in small steps and will need to test their assumptions through data over and over again.

So, was the “Linda” campaign ultimately a successful use of social media data? Yes, in the sense that it yielded tens of thousands of new connections, which in turn could be leveraged for marketing purposes. It accomplished the stated objectives of making Virgin Atlantic known to more people, building its brand image, engaging customers, and building a user base. However, it is not clear whether it was a success in sales and whether the marketing investment has returned a profit. This is mainly due to the fact that we do not know if a consumer who “liked” something on Facebook developed into a customer who “spent” money. In the next section, we will turn our attention to the more complex issue of finding and measuring this sales intent.

The Linda campaign, while successful, points to a dilemma for any business using social media for marketing. The holy grail for any brand campaign is to link its marketing actions to a solid financial return. The missing link here between brand awareness and the sales is the intention to purchase. There are two possible questions to be asked with regards to purchase intent:

How do you find customers with the right purchase intent, i.e., how do you focus sales resources at the right moment to create the greatest likelihood of sales?

How do you create purchase intent out of awareness? Social media has been seen for a long time as a tool to accomplish this, particularly in terms of the idea that word of mouth, combined with some kind of influencer, will create such purchase intent.

Let’s look at both questions in the following sections.

The easiest way to spot purchase intent is if the customer tells us that he or she intends to buy. We all know this from the traditional sales floor. As soon as a customer tells a sales representative that he or she would like to buy a certain product, the sales person knows that he has a potential lead.

In the online world, the best parallel is the search term the user is using. If you query your favorite search engine for “cheap flights to Florida,” it is likely that you have a purchase intent to buy those flights. Online advertising became the major success story for search engines such as Google. The question for data scientists was which search strings will create the highest close rate. While this is not a simple question, there are many ways to model this problem.

The more complex question, however, is how much you should pay for a given keyword. For a long time, online search advertisers have mixed up cause and correlation. If a search advertisement would cause the consumer to buy, then a big part of the marketing budget should be focused on online search. However, in reality the user may have seen an offline advertisement such as a television spot, he might have heard about the brand via friends, he may have read articles about the brand, and so forth. Thus, he might have gone through many interactions before finally typing in his search term.

The CEO of a media company we supported once complained: “When we publish an article on how good olive oil is for your overall health, our clients will go online and look for olive oils. They will most likely buy something we have recommended in our publication. However, the search engine will get the money, not us.”

It is probably safe to say that search engine advertisement has very little to no causal effect on the intent to buy. The consumer had a predefined intent, and the search engine added no value to it except matching already existing purchase intent with the possibility to buy. For a long time, however, Google received all of the value attributed to the success of a sale. To compare this with an example in sports, this would be like attributing all the success of a game to the player who finally scored the winning goal, neglecting the team who helped to lay the foundation.

But what creates intent? What triggers people to buy? The paradox is that the more we move away from a clear formulation of an intent (for example, by querying a search engine), the more difficult it will be to actually understand intent. There are, however, clues to make intent visible:

While behavioral targeting has existed for a number of years, and we know that on average it is not as effective in predicting purchase intent, social media has created the dream that if you know all my friends and all my discussions with my friends, you would be able to actually predict when I am looking for an article before I query the search engine. This was the dream and the hope brought to you by the word “social.”

Let’s look at these promises in detail, from the vantage point of both behavioral targeting and social targeting.

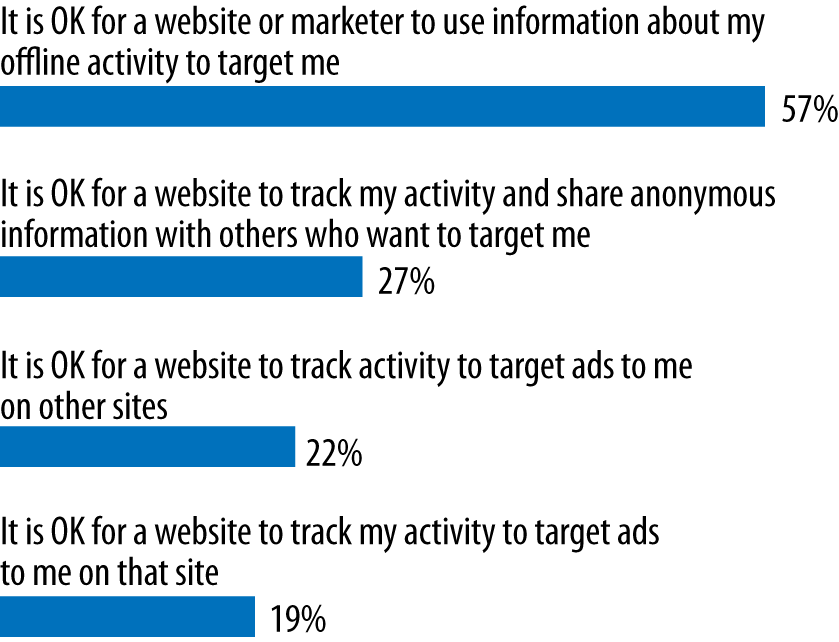

Behavioral targeting can be defined as trying to infer purchase intent based on a consumer’s online behavior. For example, “browsing the Web” can be monitored. With every page the user calls up, a cookie can be placed to see what the user is reading. Cookies are effectively used to analyze what people look at and draw conclusions that people exhibiting similar reading behavior have a high chance of buying a certain product or reacting positively to a certain advertisement. Assuming actual intent based on historical behavior is called “behavioral targeting.” Behavioral targeting has been a huge research area for many marketing companies. Today it is standard that every website places some kind of cookie on your computer to keep track of who you are and what you do. This kind of “spying” is often criticized, as consumers all over the world perceive this kind of “silent watching” as creepy.

Browsing, however, is often much less intentional then searching within a sales engine (such as Travelocity for airline tickets or Amazon.com for books). If I am reading an article about Florida, one can assume that I have an interest in Florida. However, this will not necessarily mean that I have the intention to buy a flight to Florida. I might just have a general interest in Florida and no plans to visit. And even if I do plan to visit Florida, it is by no means clear when I would like to purchase a ticket. Thus user interest online displays a higher “entropy”[28] and is less likely to relate to an intent than a search query.

However, to understand the moment of intent earlier would be highly valuable for many online companies. This is the quest of behavioral targeting. What does this mean? Behavior targeting tries to draw a conclusion of your behavior in order to know what you want before you voiced it. In short, you look at websites the average user has looked at before performing an action, then find users with a similar behavior. Based on this pattern, we assume that you are about to want something specific and so we offer you a trigger to take an action before you go and ask a search engine.

Behavioral targeting started in the 1990s, and its models used to be highly manual. For example, a media agency would aim for a target group “sports car interest,” and the technology partner for that agency would translate this into certain limits in its system, such as, “Display this online advertisements to users who have read three automotive articles this week and at least two articles about sports.” The biggest shortcomings of such a system was this kind of manual work. Someone had to assume that “sports car interest” translates into a certain reading behavior. If this assumption were wrong, behavioral targeting would not be very effective.

Such guess work and linear rules were not a good approach to reduce the entropy of user behavior. However, the more information we collected about users, the more companies built automated models and dug into the long tail by applying machine-learning mechanisms. Today, companies like Rocket Fuel or group M build models to reduce this kind of “entropy” by analyzing the total consumption behavior of many users and comparing them to the one who in the end bought a flight to Florida. Patterns about the kind of articles or the kind of content that precedes a flight booking to Florida will emerge without manual assumptions. Companies like Semasio take it even a step further and create even more rich patterns by moving from category-based analytics to semantic analytics of each page (see How does a machine-learning approach work within behavioral targeting?).

Not surprisingly, the best prediction for intention is if the consumer states an interest clearly, similar to what he or she would have done with a search query. If, for example, the user puts an item into his online shopping basket but never checks out, there is a high likelihood that he had an intent to buy such an item. This type of behavioral targeting is called “re-targeting.” However, this does not necessarily clarify cause and effect. We do not know why the consumer put the item in his basket; all what we know is that he has an intent. We do not know where this intent came from.

Despite recent advances in behavioral targeting, it still does not always work smoothly. In a recent post, Avinash Kaushik (@avinash), a knowledgeable expert in web analytics, complained about how bad targeted advertisements still are. Despite a long cookie history at ABC News, he still gets served ads badly fitting his needs.

There is nothing in my history or cookies to suggest I want botox or to lose weight or am interested in e-cigarettes (who the heck is!). [...] I don’t know who the ad provider is. But there is no way these ads are going to save ABC News. And people blame the Internet for killing the news business.[30]

The underlying issue in this case is that the content providers—in this case, ABC News, which has a cookie history of Avinash, is most likely not sharing these insights with the advertiser. ABC News knows that owning information on Avinash can be a competitive advantage for them, and thus will probably not easily distribute this information to others.

While behavioral targeting focuses on what an individual does online, social targeting uses consumers’ behavior within their social graph online to predict purchase intent. Examples of this can range from Facebook ads served based around your activities on the site all the way to targeted marketing based on the demographics of the people you are connected with online. It’s based on the old Assyrian proverb, “Tell me your friends, and I’ll tell you who you are.” Social targeting represents a source of tremendous interest and promise for marketing. Social targeting can use, for example, the posts and comments you make to others, the pages you “like,” your connections, and the activities of these connections. All that information contains “hints” that could be used to impute purchasing intent.

But it still seems to not work well yet. The apparent master of current social and behavioral targeting—Facebook—appears to still be worse off than the current best-in-class advertiser, Google. These two channels represent the difference between “searching the Web” (in Google’s case) and “talking within social media” (in Facebook’s case). So, for example, if you are trying to find the highest level of purchasing intent, should you advertise using Google AdWords (which streams your ad in Google based on user search terms) or Facebook?

According to a recent WordStream study, Google AdWords still offers 10 times higher click-through rates (CTR).[31]

There are probably three major ways by which marketeers hope to translate social signals like our social graph or a discussion with our friends into signals of intent which could trigger a purchase:

You say it.

You like it.

Your friends do it.

More and more advertisers will use this kind of data to place their advertisements more effectively. But as we will see when we go through those three points one by one, none will be as effective in predicting your purchase desire as the data of a formulated search goal like the one Google records.

The best situation is that you actually casually announce that you would like to do something. However, these situations are rare, as we are not always stating our intent out loud to our friends in public. Moreover, any marketeer realizes that what people say does not always translate to what they want or do. Nevertheless, some companies are actively using social media conversations for marketing purposes, often through the efforts of a “community manager” to engage people and try to trigger an action. For example, when I (Lutz) once shared my frustration by tweeting, “Spent an hour solving conflicts with PayPal,” it did not take long for the community manager from Paytoo, an up-and-coming competitor, to react, “Try Paytoo.com! We take pride in our customer service!” (see Figure 1-5).

Surely one can also “trigger” a situation where “you say it” to “influence” your friends. However, since direct statements of interest are rare, particularly in a publicly watched social network, a more subtle form of marketing often needs to be used.

To “like” something, in a social media sense, is similar to “saying” that you “like” it, but with two fundamental differences:

The action creates structured data, and is thus easier to understand, while to “say” that you like something is unstructured data and requires some analytical understanding first.

To “like” is easier than to say that you like something. It is a click versus a few words, which means more people will do it, and it becomes easier to measure.

Note

This phenomenon is part of a broader trend: the evolution of least effort in the Internet, where interactions have become smaller and smaller. While initially one had to write a blog post to share desires and ideas, it has now become as easy as the click of a mouse: select like and a statement is made. These likes overall will build up a personalized track record of what you are interested in, which in turn could be used to better send you a trigger for your interests.

The idea is that marketeers can predict the right intent trigger if they know what you generally have “liked.” Many likes together might create a stronger signal for interpretation than, for example, behavior targeting information. If you know that your customer has read certain stories on a newspaper, it still does not tell you anything about his feelings, position, or consent toward those stories. However, so far there has not been any major study on this subject, especially since the most “likes” are owned by one social media company. Moreover, this phenomenon is still in its early days: perhaps if you have hundreds of billion of likes, you may be able to map out something as diverse as the human interest effectively.

Nevertheless, many companies try to build a business on this. Circle Me is, for example, a young Italian startup founded by Giuseppe D’Antonio. Their major business model is to collect likes from all different sources, of which Facebook could be only one. As we will see in the next chapters, neither likes nor friends truly reveal our intentions, so to have a collection of likes will be mainly useful for brand awareness purposes, as described previously.

Tell me with whom thou art found, and I will tell thee who thou art.

—Johann Wolfgang von Goethe[32]

So far, the area we know most about is the behavior of you and your friends, in such a way as to “marry” behavioral targeting with social network information. The underlying assumption is that your friends’ behaviors are a good proxy of your own behavior. The buzzwords here are “word of mouth” and “influencer.” But how effective is this in reality?

We all know word of mouth from our own anecdotal experience. We ask friends for advice. Did you recently move to a new town? You probably asked your friends which neighborhood to move to, which school to send your kids to, and the like. If you did this online via a social network, then perhaps this is a way to see intention in the making? Or better yet, do social networks play a pivotal role in influencing peoples’ decisions?

The traditional view is that only a few people will have a big impact over us. Malcolm Gladwell called it 2,000 in his book The Tipping Point (Back Bay Books) the “law of few.”[33] However the idea that a few people determine what we like, think, and do has been around for a while. Katz and Lazarsfeld called them opinion leaders back in 1955,[34] followed by Merton who called them “influentials” (1968),[35] up to Gladwell and the PR agency Burson Marsteller, who now calls them e-fluentials. Those influencers tell us what to do, as depicted in Figure 1-6, and we all have anecdotal evidence where someone helped us make a decision. If we move to a new town, most of us will contact friends who are familiar with that town to ask about schools or doctors to use. As human interaction moved now partly online, the hopes are that those influencers are also online in social networks.

There are many success stories that social media referrals have an influence. Henry Blodget (@hblodget) from Business Insider provides a few examples:

Rent the Runway has 200% higher conversions from social referrals from fashion magazines than from paid search.

ShoeDazzle says that Facebook-connected users are 50% more likely to make monthly repeat purchases.

Friends referred by friends at One Kings Lane have twice the lifetime value of customers from other channels.

When a Facebook user clicks on a Ticketmaster purchase shared by a friend, it is worth between $6 and $8 in new ticket sales.

Each viewed video on YouTube creates a 3% chance that someone will click on the “buy” link at the end.

Many more anecdotal examples exist of the influence of social connections on purchasing behavior. You can also infer purchasing intent from the nature of an online community and/or its past behavior. For example, a network of people who own Ford Mustang automobiles—a highly committed consumer group that often spends money to customize these vehicles in the aftermarket—may have a stronger correlation with purchasing intent versus people who discuss, say, bowling, but are not necessarily in the market for more bowling balls.

Given the impact of influencers, we as marketeers only need to spot and target them with the correct marketing message to multiply their influence. Sounds exciting, right? Or as Rand wrote in 2004, “Influencers have become the ‘holy grail’ for today’s marketeers.”[36] But can we deduce from examples such as these—of which there are many in print—that social marketing is “the next big thing” in social advertising? Do those influencers even exist?

The answer, once again, is yes and no. Those “few” influencers as Gladwell described them do not exist. We are fortunately not the kind of lemmings depicted in Figure 1-6. However, surely the process of influencing exists. It is only way more complex then many social media tools make us believe. When we move from anecdotes to formal literature, we will understand the role of influence between peers. In the next sections, we will describe how:

So how do we differentiate real influence that spreads from social connections from homophily, where people flock by affiliation? As one example, Kevin Lewis from Harvard tried to analyze how taste spreads.[37] Who is influencing the taste of whom? Over the course of four years, he interviewed college students and monitored their Facebook friends, and his conclusion on how taste spreads is that “it depends” on the topic. For example, he found that students do influence one another’s taste in classical or jazz music. However, indie music acts anti-correlated. So if I have someone within my network who likes a certain indie direction, it seems that I am less likely to like on this same direction. This might be because listeners of the indie music want to be more “independent.”

Moreover, Kevin Lewis et al. found that we overestimate influence. In many of his samples he could not find statistical relevant proof that one person was influencing the other. Nevertheless students with similar taste form communities more often than those without this similar taste. This is not due to influence, but a phenomenon known as “homophily” (literally translated as “love of the same”): people become friends in the first place because of common, shared interests that already exist. In other words, your friends like things because you do. We tend to hang out with people who share the same visions, like the same sports, or have similar opinions as we do. Thus the more friends you have in one special interest group, the more likely it is that you fall into the same interest group.

Our friends can be a good predictor of our interests, and in turn may serve as a good proxy to make us receptive to branding advertisments. But at present, they do not seem to be a good predictor of our intentions or our actions.

Even if there is no influencer, can the selection of our friends, even when we had selected them out of homophily, help advertisers to target our needs better? One of the key questions of social targeting is whether it can be superior to behavioral targeting or even analysis of search terms. In other words, does studying the behavior of your social connections add value to assessing your potential purchasing behavior as compared to simply studying you?

Kun Liu and Lei Tang from Yahoo! Labs did one of the most extensive studies to date on the influence of friends’ behavior on behavioral targeting in an online network.[38] Using the resources of Yahoo, the authors examined the predictive impact of social data for more than 180 million users across 60 consumer domains, over a period of two and a half months.

The authors figured that users were more likely to click at a given online ad in a certain behavioral targeting (BT) category, if they had at least one of their friend in their network who clicked into the same category.

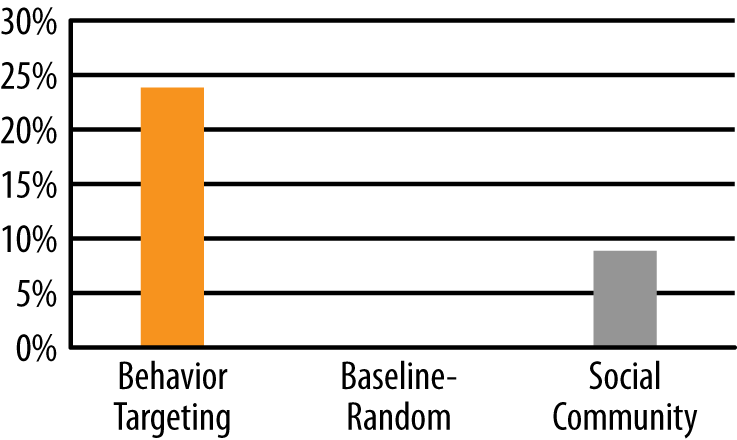

Can we conclude that users will have similar intent and follow similar actions if we know that their networks share similar interests? Not necessarily. Despite this measured uplift, Liu et al. could not find that ad targeting based on social connections performed better than traditional behavioral targeting. The metrics to best use for comparing those different approaches is the area under the curve between click-through rate (CTR) and reach. Those two metrics influence each other. The more sure you are that a person will click, the fewer people you can address. On the other hand, the more you spread the advertisement to many viewers, the lower the probability will be that someone clicks. Liu et al. used several methods to calculate an uplift through the social community. Figure 1-7 compares the average of those attempts versus the traditional behavior targeting. As it turns out, behavior targeting—meaning we display ads based on the content what you have read—is more than twice as effective as any of the suggested social targeting approaches. The baseline in Figure 1-7 indicates that the ads are displayed at random without any further calculation.[39] The best results, however, were obtained by combining both sides, the social network information as well as the behavioral information.

So far we have discussed the effectiveness of ad placement. Looking at different questions (Chapter 8) will alter the effectiveness of the social connections. Let’s look at the adoption rate of a product. For example, a study from Bhatt et al.[40] analyzed the adoption rate from a PC to Phone product. Bhatt et al. did find influence. However he did not find what Gladwell called[41] the “law of the few.” An hypothesis that some few “external influencers” can influence our daily actions. But he found that the product adoption was more strongly influenced by direct peers as compared to external influencers. Thus not a few but many different individuals seem to influence our decisions. Other research has found similar type of influence. Especially for products with strong network externalities one often finds that the influence is growing strongly the more of your peers adopt a product. This is quite the opposite to the proposed “law of the few.” Similar is true for certain situations, such as a purchase decision. Social media can clearly be influential here. The best example are reviews: 22% of users indicate that their purchase decision was influenced by a review (Figure 1-8). For electronic goods, this rate goes up to 33%.[42]

The conclusion? Social targeting appears to hold promise for creating awareness and branding, and one can see this in the previous example about Facebook’s promoted stories. But it is just an incremental improvement. Social targeting will neither reduce the importance of search, which is still the best predictor for intent, nor the importance of behavioral targeting, which is still the second best predictor. However, social targeting does incrementally improve the predictions done by behavioral targeting as shown by Kun Liu.

But what is influence then? Whether you can be influenced or not depends on three different factors:

You are ready to be influenced. This is the the case of reviews. Users want to be influenced. They are looking for an answer.

The topic is right. As we saw in the last sections, there is a topic dependence for influence.

The influencer needs to have contact to you. Thus some form of reach is necessary, but not a sufficient criterion for influence.

Very often the term “influence” within social networks is reduced to reach. Without reach, we will have difficulties influencing someone. However, even with reach, there is no certainty that we can. Bakshy from the University of Michigan found such results in 2011 by looking at the spreading of Twitter information, tracking 74 million events across 1.6 million Twitter users, and found that propagation via social networks is not predictable.[43] That means that we cannot predict whether a certain link, joke, or piece of information will spread only by looking at the reach someone can create. Hold on, you might think. We all know the stories about that one tweet that went around the world. What is with these situations? Well, we could call them luck, because if you try to build a deterministic model of when a tweet is going to spread and when it will not, you will fail. It remains hard, if not impossible, to quantify the phenomenon of influencers.

What we can say for sure is that information from well-connected people does spread better, and we will look at this in the next chapter on public relations (Chapter 3). However, these spreading effects can perhaps be more easily explained by either a pure broadcasting phenomenon (where the “spread” among social network users is analogous to each of them seeing, say, a television ad) or by homophily. Thus we still should discuss, at least briefly, typical measures of how reach within a network is measured.

A key factor here is the concept of centrality within a network. This is a very important metric for information dissemination. If a person is quite central, we frame that person as being a broadcaster. Note that often influence could be happening at a micro level on the edges of a personal network, in those moments where you talk to new nodes that are not yet part of the network, and by doing so are influencing them to become a part of that network.

Others look at the reach of a message and how often others engage people with this message. Again, we would claim that this is not necessarily influence but a more PR-centric measure. We have also assumed that the actual metrics are easily available. There are many metrics available from many tools. Most of those tools analyze the influence of the person, including Klout, Kred, PeerIndex, and Traackr. Many other tools also have some form of “importance” measurement as part of their offering, such as Fisheye Analytics, Radian6, Sysomos, and others. Also you will find tools that restrict themselves to only one media type, such as Twitter. Twitter offers a nice structure, which enables assessing your network quite easily. Services like TweetLevel, TweetReach, Twitalyzer, and TwitterGrade are good ones to check out.

Social media has created a whole new discipline in marketing. It is different from traditional methods of marketing, and thus measurements are very important in guiding our efforts. What has an effect and what does not? In order to find this out, you need to first understand why social media is different and should not be measured with the same tools you have used before. Despite these different measurements, you somewhere need to bring all measures back together to make efforts comparable.

The effect is different for each business, but in summary, one can say:

Social media marketing has been overhyped, and solid metrics have not yet been applied.

The effect of social media marketing is visible but not as pronounced as assumed.

Social media channels are particularly good for the distribution of information or as a vehicle for branding.

Since distribution of information—reach—is no guarantee for purchase intent, it is as hard to quantify ROI, as is the case with any other image campaign.[45]

The ultimate aim of social media marketing is to drive sales intention through awareness. We therefore break down the different levers of intention mainly into behavioral clues (behavioral marketing) or social clues (social marketing). Behavioral clues such as your search behavior will be the best data to answer the question about future behavior. Thus behavior clues are best to uncover the fourth “V” of data. But social clues such as what you or your friends say are becoming more and more an important metrics to predict intention.

Here there has been a lot of hope placed onto influencers: people to whom you are socially connected and who can drive up your intention. We know from anecdotal evidence that social media should have an effect on purchase decisions. But the assumed “law of few” means that the influencer effectively does not exist. Influence is more a function of a readiness to be influenced, and that depends very much on the topic as well as reach. For example, in the case discussed earlier of the adoption of the PC to a phone product, peer pressure played a role, and thus social media’s ability to broadcast and connect with others multiplied the effect.

In closing, social media does have unique advantages as tools in marketing. For branding, social media can create a more sticky reach with greater consumer engagement, and in finding purchasing intent, it can add an incremental step to behavioral targeting. Will it spread brand awareness and increased sales of your product on a massive scale? In all likelihood, only for the lucky few. But for all of us, the right metric in social media marketing can mean the difference between success and failure.

How to measure social media and how to use social media in your own marketing depends very much on your business. To get you thinking, let’s look at the following workbook questions. How does your company use social media? Social media is a broad and fuzzy category. Go back and look at the seven different categories that can be used to describe social media. Now let’s dig into some descriptive measures of social media:

What are the realistic costs to the organization?

How would you define a branding impact of social media?

Are the measurements your company set up really smart? (Please see further discussion on the right question in Chapter 8.)

Looking at your marketing teams, are they measured by metrics that could lead to wrong measurement behavior? (Please see further discussion on misused metrics in Chapter 10.)

ROI is a hot topic for any organization. Can you quanitfy it? How do you make sure not to have any lurking variables within your ROI calculation?

Since the ROI discussion is such an important one in the area of social enabled marketing, please share your approach. Solved or not? Silver bullet or not? Please explain your ROI measurement on our LinkedIn or Facebook page.

Further to the descriptive measures, let’s look into predictive measures using the data from the social media campaigns you are using:

What are levers of purchase intent? Where is the value to predict future consumer behavior in your data?

Can you predict purchase intent using social or behavioral clues?

What are the best features of your data set? Past purchases? Country? Age? Reading behavior? Published comments?

Can you improve purchase intent by using social strings such as influencers or social peer pressure? By how much?

[13] Wikipedia contributors, “Marketing,” http://bit.ly/1dcOa97. Accessed 7 November 2013.

[15] Kevin Lewis et.al., “Social selection and peer influence in an online social network”, PNAS, Jan 2012, http://bit.ly/1coTups.

[16] Roxane Divol, David Edelman, and Hugo Sarrazin, “Demystifying social media,” McKinsey Quarterly, April 2012, http://bit.ly/1coTups.

[17] Stuart Kemp, “Global TV Ad Market To Grow By $60 Billion By 2017, Report Says,” Hollywood Reporter, Dec 2011, http://bit.ly/18UOX37.

[18] Kalev Leetaru, “#bdw12 Introduction,” Big Data Week, http://bit.ly/1kA7rW8.

[19] Kaplan and Haenlein, “Users of the world, unite! The challenges and opportunities of Social Media,” Business Horizon, 2010, http://bit.ly/18UPUs1.

[20] Tudou is the video-sharing website in China.

[21] Coca-Cola Content 2020, http://youtu.be/LerdMmWjU_E

[22] We will later explain that the term “virality” is wrong and it should rather be called “contagiousness.”

[23] Virgin Atlantic ad, Guardian, RKCR, October 2010, http://bit.ly/1gpMGiD.

[24] CUSTORA E-Commerce Customer Acquisition Snapshot, 2013, http://bit.ly/1e5VUQF.

[25] Carolyn Heller Baird et. al., “From social media to Social CRM: What customers want,” IBM Institute for Business Value, 2011, http://ibm.co/1aVPHPu.

[26] This survey includes respondents who answered “yes” and “yes, with some visibility/control.”

[27] Krux, Krux Consumer Survey, Jan 2011, http://bit.ly/1dqHar4.

[28] “Entropy” is used here as measure of disorder that resuts in a higher uncertainty.

[29] Kasper Skou, “Making behavioral targeting work,” March 2012, http://bit.ly/18UWuPp.

[30] Avinash Kaushik, “Why I’m wary of Display Advertising,” Google Plus, Jun 2012, http://bit.ly/1dqIwSB.

[31] WordStream, “New Research Compares Facebook Advertising to Google Display Network: Who Comes Out on Top?” May 2012, http://bit.ly/1iXBuvi.

[32] This proverb seems to have many origins. There are similar Assyrian, Russian, English, German, and Dutch proverbs. A similar quote has also been attributed to Miguel de Cervantes.

[33] Gladwell, Malcolm, The Tipping Point: How Little Things Can Make a Big Difference, New York: Back Bay Books, 2002.

[34] Katz, Lazarsfeld, “Personal Influence: The Part Played by People in the Flow of Mass Communications,” 1955

[35] Robert Merton, “Patterns of influence Local and cosmopolitan influentials,” Social Theory and Social Structure, 1868

[36] Paul M. Rand, “ Identifying and Reaching Influencers,” American Marketing Association Journal, http://us.prolog.biz/resource1.html.

[37] Kevin Lewis et al., “Social selection and peer influence in an online social network,” PNAS, Jan 2012, http://bit.ly/1coTups.

[38] K Liu and L Tang, “Large-Scale Behavioral Targeting with a Social Twist”, ACM International Conference on Information and Knowledge Management, October 2011, http://labs.yahoo.com/node/597

[39] Data taken from the study conducted by Liu et al.

[40] Rushi Bhatt et al., “Predicting Product Adoptions in Large Social Networks,” 2010, http://bit.ly/1iKyvW3.

[41] Gladwell M., The Tipping Point: How Little Things Can Make a Big Difference, Little, Brown, New York, 2002.

[42] “Consumers now pay more attention to online reviews than word-of-mouth,” accomplished, May 2012, http://bit.ly/18mwNGN.

[43] Eytan Bakshy, “Everyone’s an Influencer: Quantifying Influence on Twitter,” 2011, http://bit.ly/1kAqqjb.

[44] http://1.usa.gov/1gpXxc7

Get Ask, Measure, Learn now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.