| Principles and properties | Structures | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Versatility | ✓ | Module | |

| ✓ | Conceptual integrity | ✓ | Dependency |

| ✓ | Independently changeable | Process | |

| ✓ | Automatic propagation | Data access | |

| ✓ | Buildability | ||

| Growth accommodation | |||

| Entropy resistance |

Since the earliest tintypes and daguerreotypes, we have always seen photographs as special, sometimes even magical. A photograph captures a fleeting moment in time, in a way that our fallible memories cannot. But the best portraits do more than just preserve a moment; they illuminate it. They catch a certain glance or expression, a characteristic pose that lets the subject’s personality shine through.

If you’ve had children in a U.S. school, you probably already know the name Lifetouch. Lifetouch photographs most elementary school, middle school, and high school students in the United States every single year. What you may not know is that Lifetouch also runs high-quality portrait studios. Lifetouch Portrait Studios (LPS) operates in major retail stores across the country, along with the “Flash!” chain of studios in shopping malls. In these studios, LPS’s photographers take portraits that last a lifetime.

Digital photography has transformed the entire photography industry, and LPS is no exception. Giant rolls of film and frame-mounted cameras are disappearing, replaced with professional-grade DSLRs and flash memory cards. Unfettered photographers can move around, try different angles, and get closer than ever to their subjects. In short, they have more freedom to take those great portraits. The photographer works with the camera to turn photons into electrons, but somehow, somewhere, some system has to turn those electrons into atoms of ink and paper.

In 2005, my colleagues and I from Advanced Technologies Integration (ATI) in Minneapolis worked together with developers from LPS to roll out a new system to do exactly that.

Two dynamics drive a system’s architecture: What must it do? What boundaries must it work within? These define the problem space.

We create, and simultaneously explore, the solution space by resolving these forces, navigating the positive pole of required behavior and the negative one of limitations. Sometimes we can create elegance, and even beauty, when the answers to individual constraints mesh together into a coherent whole. I’m happy to say that the Creation Center project did just that.

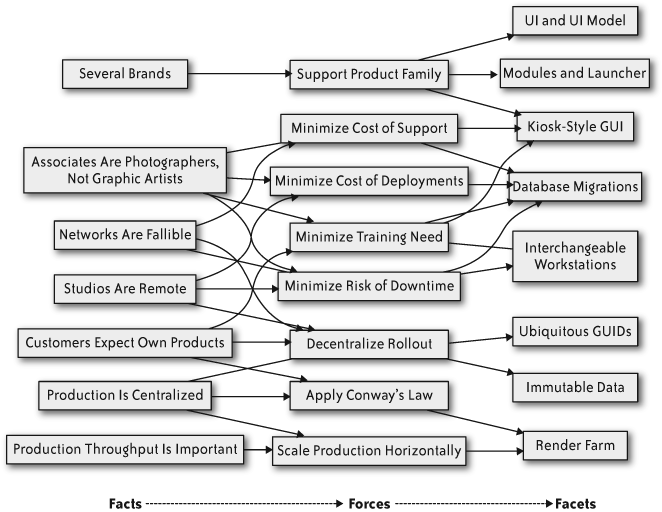

On this project, we faced several incontrovertible facts. Some are just the nature of the business; others could change, but not within our scope. Either way, we regarded these as immutable. These facts make up the left column in Figure 4-1.

- Several brands

LPS supports multiple brands today and could add more in the future. At a minimum, Creation Center would have two visually distinct skins, and adding skins should not require extensive effort.

- Associates are photographers, not graphic artists

Photographers are trained to use the camera, not Photoshop. When an inexperienced user sits down at Photoshop, the most likely result is a lousy image. It’s a power tool for power users, and there should be no need for a photographer in a portrait studio to get up the Photoshop learning curve. Photoshop and its cousins would also slow down studio workflow. Instead, studio associates need to create beautiful images rapidly.

- Studios are remote

Studios are geographically dispersed, with little to no local technical support. Hardware deliveries or replacements require shipping components back and forth.

- Networks are fallible

Some studios have no network connections. Even for the ones that do, it’s not acceptable to halt the studio if the connection goes down.

- Customers expect their own products

Customers should receive their photos with their designs and text.

- Production is centralized

High-quality photographic printers are becoming more common, but making products that can last for decades requires much more expensive equipment.

- Production throughput is important

The same printers are also the constraint in the production process. Therefore, every other step in the process must be subordinated to the constraint.

These facts lead to several forces that we must balance. It’s common to perceive the forces as fundamental, but they aren’t. Instead, they emerge from the context in which the system exists. If the context changes, then the forces might be nullified or even negated.

We chose a handful of constructs to resolve these forces. The rightmost column of Figure 4-1 shows these facets of the architecture. Of course, these aren’t the only Creation Center features worth discussing, but these facets of the architecture are of general interest. I also think they simultaneously illustrate a nice separation of concerns and mutually supporting structures.

Before digging into the specific features, we need to fill in one more piece of context: the system’s workflow.

Get Beautiful Architecture now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.