Elements

are the

basis of CSS display. In HTML, the most common elements are easily

recognizable, such as p, table,

span, a, and

div. In XML languages, the elements are defined by

the language’s

Document Type Definition (DTD). Every

single element in a document plays a part in its presentation. In CSS

terms, at least as of CSS2.1, that means each element generates a box

that contains the element’s content.

Although CSS depends on elements, not all elements are created

equally. For example, images and paragraphs are not the same type of

element, nor are span and div.

In CSS, elements generally take two forms: replaced and nonreplaced.

The two types are explored in detail in Chapter 7, which covers the particulars of the box

model, but I’ll address them briefly here.

Replaced elements

are

those where the element’s content is replaced by

something that is not directly represented by document content. The

most familiar XHTML example is the img element,

which is replaced by an image file external to the document itself.

In fact, img has no actual content, as you can see

by considering a simple example:

<img src="howdy.gif" />

This code snippet contains no actual content—only an element

name and an attribute. The element presents nothing unless you point

it to some external content (in this case, an image specified by the

src attribute). The input

element is also replaced by a radio button, checkbox, or text input

box, depending on its type. Replaced elements also generate boxes in

their display.

The majority of HTML and XHTML

elements are nonreplaced elements. This means

their content is presented by the

user agent (generally a

browser) inside a box generated by the element itself. For example,

<span>hi

there</span> is a nonreplaced element, and

the text “hi there” will be

displayed by the user agent. This is true of paragraphs, headings,

table cells, lists, and almost everything else in XHTML.

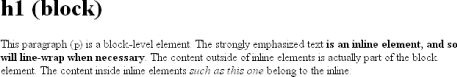

In addition to replaced and nonreplaced elements, CSS2.1 uses two other basic types of elements: block-level and inline-level. These types will be more familiar to authors who have spent time with HTML or XHTML markup and its display in web browsers; the elements are illustrated in Figure 1-1.

Block-level

elements

generate an element box that (by default) fills its parent

element’s content area and cannot have other

elements at its sides. In other words, it generates

“breaks” before and after the

element box. The most familiar block elements from HTML are

p and div. Replaced elements

can be block-level elements, but they usually are not.

List items are a special case of block level elements. In addition to behaving in a manner consistent with other block elements, they generate a marker—typically a “bullet” for unordered lists and a number for ordered lists—that is “attached” to the element box. Except for the presence of this marker, list items are in all other ways identical to other block elements.

Inline-level elements

generate an element

box within a line of text and do not break up the flow of that line.

The best inline element example is the a element

in XHTML. Other candidates would be strong and

em. These elements do not generate a

“break” before or after themselves,

and so they can appear within the content of another element without

disrupting its display.

Note that while the names “block” and “inline” share a great deal in common with block- and inline-level elements in XHTML, there is an important difference. In HTML and XHTML, block-level elements cannot descend from inline-level elements. In CSS, there is no restriction on how display roles can be nested within each other.

To see how this works, let’s consider a CSS property.

You may have noticed that there are a lot of values, only three of

which I’ve even come close to mentioning:

block, inline, and

list-item. We’re not going to

explore the others now, mostly because they get covered in some

detail in Chapter 2 and Chapter 7.

For the moment,

let’s just concentrate on block

and inline. Consider the following markup:

<body> <p>This is a paragraph with <em>an inline element</em> within it.</p> </body>

Here we have two block elements (body and

p) and an inline element (em).

According to the XHTML specification, em can

descend from p, but the reverse is not true.

Typically, the XHTML hierarchy works out such that inlines can

descend from blocks, but not the other way around.

CSS, on the other hand, has no such restrictions. You can leave the markup as it is but change the display roles of the two elements like this:

p {display: inline;}

em {display: block;}This would cause the elements to generate a block box inside an inline box. This is perfectly legal and violates no specification. The only problem would be if you tried to reverse the nesting of the elements:

<em><p>This is a paragraph improperly enclosed by an inline element.</p></em>

No matter what you do to the display roles via CSS, this is not legal in XHTML.

While changing the display roles of elements can be useful in XHTML documents, it becomes downright critical for XML documents. An XML document is unlikely to have any inherent display roles, so it’s up to the author to define them. For example, you might wonder how to lay out the following snippet of XML:

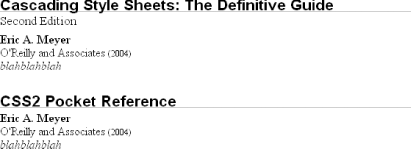

<book> <maintitle>Cascading Style Sheets: The Definitive Guide</maintitle> <subtitle>Second Edition</subtitle> <author>Eric A. Meyer</author> <publisher>O'Reilly and Associates</publisher> <pubdate>2004</pubdate> <isbn>blahblahblah</isbn> </book> <book> <maintitle>CSS2 Pocket Reference</maintitle> <author>Eric A. Meyer</author> <publisher>O'Reilly and Associates</publisher> <pubdate>2004</pubdate> <isbn>blahblahblah</isbn> </book>

Since the default value of display is

inline, the content would be rendered as inline

text by default, as illustrated in Figure 1-2. This

isn’t a terribly useful display.

You can define the basics of the layout with

display:

book, maintitle, subtitle, author, isbn {display: block;}

publisher, pubdate {display: inline;}You’ve now set five of the seven elements to be

block and two to be inline. This means each of the block elements

will be treated much as div is treated in XHTML,

and the two inlines will be treated in a manner similar to

span.

This fundamental ability to affect display roles makes CSS highly useful in a variety of situations. You could take the preceding rules as a starting point, add a number of other styles, and get the result shown in Figure 1-3.

Throughout the rest of this book, we’ll explore the various properties and values that allow presentation like this. First, though, we need to look at how one can associate CSS with a document. After all, without tying the two together, there’s no way for the CSS to affect the document. We’ll explore this in an XHTML setting since it’s the most familiar to people.

Get Cascading Style Sheets: The Definitive Guide, Second Edition now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.