A lot of CSS properties, such as margins, depend on length measurements to properly display various page elements. It’s no surprise, then, that there are a number of ways to measure length in CSS.

All length units can be expressed as either positive or negative

numbers followed by a label (although some properties will accept

only positive numbers). You can also use real numbers—that is,

numbers with decimal fractions, such as 10.5 or 4.561. All length

units are followed by a two-letter abbreviation that represents the

actual unit of length being specified, such as in

(inches) or pt (points). The only exception to

this rule is a length of 0 (zero), which need not

be followed by a unit.

These length units are divided into two types: absolute length units and relative length units.

We start with absolute units because they’re easiest to understand, despite the fact that they’re almost unusable in web design. The five types of absolute units are as follows:

- Inches (

in) As you might expect, this notation refers to the inches one finds on a ruler in the United States. (The fact that this unit is in the specification, given that almost the entire world uses the metric system, is an interesting insight into the pervasiveness of U.S. interests on the Internet—but let’s not get into virtual sociopolitical theory right now.)

- Centimeters (

cm) Refers to the centimeters that one finds on rulers the world over. There are 2.54 centimeters to an inch, and one centimeter equals 0.394 inches.

- Millimeters (

mm) For those Americans who are metric-challenged, there are 10 millimeters to a centimeter, so you get 25.4 millimeters to an inch, and 1 millimeter equals 0.0394 inches.

- Points (

pt) Points are standard typographical measurements that have been used by printers and typesetters for decades and by word-processing programs for many years. Traditionally, there are 72 points to an inch (points were defined before widespread use of the metric system). Therefore, the capital letters of text set to 12 points should be a sixth of an inch tall. For example,

p{font-size:18pt;}is equivalent top{font-size:0.25in;}.- Picas (

pc) Picas are another typographical term. A pica is equivalent to 12 points, which means there are 6 picas to an inch. As above, the capital letters of text set to 1 pica should be a sixth of an inch tall. For example,

p{font-size:1.5pc;}would set text to be the same size as the example declarations found in the definition of points.

Of course, these units are really useful only if the browser knows

all the details of the monitor on which your page is displayed, the

printer you’re using to generate hard copy, or

whatever other user agent you might be using. On a web browser,

display is affected by the size of the monitor and the

resolution to which the

monitor is set—and there isn’t much that you,

as the author, can do about these factors. You can only hope that, if

nothing else, the measurements will be consistent in relation to each

other—that is, that a setting of 1.0in will

be twice as large as 0.5in, as shown in Figure 4-3.

If a monitor is set to be 1,024 pixels wide by 768 pixels tall, the monitor’s screen is exactly 14.22 inches wide by 10.67 inches tall, and the display area fills the monitor, then each pixel will be 1/72 of an inch wide and tall. As you might guess, this scenario is a very, very rare occurrence (have you ever seen a monitor with those dimensions?). So, on most monitors, the actual number of pixels per inch (ppi) is higher than 72—sometimes much higher, up to 120 ppi and beyond.

As a Windows user, you might be able to set your display driver to make the display of elements correspond correctly to real-world measurements. To try, click Start → Settings→ Control Panel. In the Control Panel, double-click Display. Click the Settings tab, and click Advanced to reveal a dialog box that may be different on each PC. You should see a section labeled Font Size, in which case select Other, and then hold a ruler up to the screen and move the slider until the onscreen ruler matches the physical ruler. Click OK until you’re free of dialog boxes, and you’re set.

If you’re a Mac user, there’s no

place to set this information in the operating system—the Mac

OS has already made an assumption about the relationship between

on-screen pixels and absolute measurements by declaring your monitor

to have 72 pixels to the inch. This assumption is totally wrong, but

it’s built into the operating system, and therefore

pretty much unavoidable, at least for now. The result is that, on

many Macintosh-based web browsers, any point value will be equivalent

to the same length in pixels: 24pt text will be 24

pixels tall, and 8pt text will be 8 pixels tall.

This is, unfortunately, just slightly too small to be legible. Figure 4-4 illustrates the problem.

The Mac display problem is an excellent example of why points should be strenuously avoided when designing for the Web. Ems, percentages, and even pixels are all preferable to points where browser display is concerned.

Tip

Beginning with Internet Explorer 5 for Macintosh and Gecko-based browsers such as Netscape 6+, the browser itself contains a preference setting for setting ppi values. You can pick the standard Macintosh ratio of 72ppi, the common Windows ratio of 96ppi, or set a value that matches your monitor’s ppi ratio. This last option works similarly to the Windows setting described above, where you use a sliding scale to compare to a ruler and thus get an exact match between your monitor and physical-world distances.

Despite all we’ve seen, let’s make

the highly suspect assumption that your computer knows enough about

its display system to accurately reproduce real-world measurements.

In that case, you could make sure every paragraph has a top margin of

half an inch by declaring p

{margin-top: 0.5in;}. No matter

what the circumstances, a paragraph will have a half-inch top margin,

regardless of font size or anything else.

Absolute units are much more useful in defining style sheets for printed documents, where measuring things in terms of inches, points, and picas is common. As you’ve seen, attempting to use absolute measurements in web design is fraught with peril at best, so let’s turn to some more useful units of measure.

Relative units are so called because they are measured in relation to other things. The actual (or absolute) distance they measure can change due to factors beyond their control, such as screen resolution, the width of the viewing area, the user’s preference settings, and a whole host of other things. In addition, for some relative units, their size is almost always relative to the element that uses them and will thus change from element to element.

There are three relative length units:

em, ex, and

px. The first two stand for

“em-height” and

“x-height,” which are common

typographical measurements; however, in CSS, they have meanings you

might not expect if you are familiar with typography. The last type

of length is px, which stands for

“pixels.” A pixel is one of the

dots you can see on your computer’s monitor if you

look closely enough. This value is defined to be relative because it

depends on the resolution of the display device, a subject

we’ll soon cover.

First, however, let’s

consider em and ex. In CSS, one

“em” is defined to be the value of

font-size for a given font. If the

font-size of an element is 14 pixels, then for

that element, 1em is equal to 14 pixels.

Obviously, this value can change from element to element. For

example, given an h1 whose font is 24 pixels in

size, an h2 element whose font is 18 pixels in

size, and a paragraph whose font is 12 pixels in size, if you set the

left margin of all three at 1em, they will have

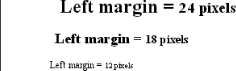

left margins of 24 pixels, 18 pixels, and 12 pixels, respectively:

h1 {font-size: 24px;}

h2 {font-size: 18px;}

p {font-size: 12px;}

h1, h2, p {margin-left: 1em;}

small {font-size: 0.8em;}

<h1>Left margin = <small>24 pixels</small></h1>

<h2>Left margin = <small>18 pixels</small></h2>

<p>Left margin = <small>12 pixels</small></p>When setting the size of the font, on the other hand, the value of

em is relative to the font size of the parent

element, as illustrated by Figure 4-5.

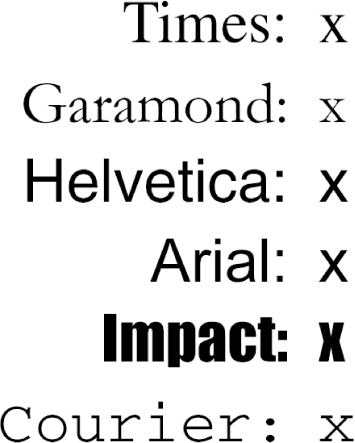

ex

, on the other hand,

refers to the height of a lowercase x in the font being used.

Therefore, if you have two paragraphs of text in which the text for

each is 24 points in size, but each paragraph uses a different font,

then the value of ex could be different for each

paragraph. This is because different fonts have different heights for

x, as you can see in Figure 4-6. Even though the

examples use 24-point text—and therefore, each

example’s em value is 24

points—the x-height for each is different.

Of course, everything I’ve just explained is

completely theoretical. I’ve outlined what is

supposed to happen, but in practice, many user

agents get their value for ex by taking the value

of em and dividing it in half. Why? Apparently,

most fonts don’t have the value of their

ex height built-in, and it’s a

very difficult thing to compute. Since most fonts have lowercase

letters that are about half as tall as uppercase letters,

it’s a convenient fiction to assume that

1ex is equivalent to 0.5em.

A few browsers, including Internet Explorer 5 for Mac, actually

attempt to determine the x-height of a given font by internally

rendering a lowercase x and counting pixels to determine its height

compared to the font-size value used to create the

character. This is not a perfect method, but it’s

much better than simply making 1ex equal to

0.5em. We CSS practitioners hope that, as time

goes on, more user agents will start using real values for

ex and the half-em shortcut will fade into the

past.

On the face of things, pixels are straightforward. If you look at a monitor closely enough, you can see that it’s broken up into a grid of tiny little boxes. Each box is a pixel. If you define an element to be a certain number of pixels tall and wide, as in the following markup:

<p> The following image is 20 pixels tall and wide: <img src="test.gif" style="width: 20px; height: 20px;" alt="" /> </p>

then it would follow that the element will be that many monitor elements tall and wide, as shown in Figure 4-7.

Unfortunately, as with all things, there is a potential drawback to

using pixels. If you set font sizes in pixels, then users of Internet

Explorer for Windows through IE6 (the current release as of this

writing) cannot resize the text using the Text Size menu in their

browser. This can be a problem if your text is too small for a user

to comfortably read. If you use more flexible measurements, such as

em, the user can resize text. (Those who are

exceedingly protective of their design might call

that a drawback, of course.)

On the other hand, pixel measurements are perfect for expressing the size of images, which are already a certain number of pixels tall and wide. In fact, the only time you would not want pixels to express the size of images is if you want them scaled along with the size of the text. This is an admirable and occasionally useful approach, and one that would really make sense if you were using vector-based images instead of pixel-based images. (With the adoption of Scalable Vector Graphics, look for more on this in the future.)

So why are pixels defined as relative lengths? I’ve explained that the tiny little boxes of color in a monitor are pixels. However, how many of those boxes equals one inch? This may seem like a non sequitur, but bear with me for a moment.

In its discussion of pixels, the CSS specification recommends that in cases where a display type is significantly different than 96ppi, user agents should scale pixel measurements to a “reference pixel.” CSS2 recommended 90ppi as the reference pixel, but CSS2.1 recommends 96ppi—a measurement common to Windows machines and adopted by modern Macintosh browsers such as IE5 and Safari.

In general, if you declare something like

font-size: 18px, a web browser

will almost certainly use actual pixels on your monitor—after

all, they’re already there—but with other

display devices, like printers, the user agent will have to rescale

pixel lengths to something more sensible. In other words, the

printing code has to figure out how many dots there are in a pixel,

and to do so, it may use the 96ppi reference pixel.

Warning

One example of problems with pixel measurements can be found in an

early CSS1 implementation. In Internet Explorer 3.x, when a document

was printed, IE3 assumed that 18px is the same as

18 dots, which on a 600dpi printer works out to be 18/600, or 3/100,

of an inch—or, if you prefer, .03in.

That’s pretty small text!

Because of this potential for rescaling, pixels are defined to be a relative unit of measurement, even though, in web design, they behave much like absolute units.

Given all the issues involved, the best

measurements to use are probably the relative measurements, most

especially em, and also px when

appropriate. Since ex is, in most currently used

browsers, basically a fractional measurement of

em, it’s not all that useful for

the time being. If more user agents support real x-height

measurements, ex might come into its own. In

general, ems are more flexible because they scale with font sizes, so

elements and element separation will stay more consistent.

Other element aspects may be more amenable to the use of pixels, such as borders or the positioning of elements. It all depends on the situation. For example, in designs that would have traditionally used spacer GIFs to separate pieces of a design, pixel-length margins will produce an identical effect. Converting that separation distance to ems would allow it to grow or shrink as the text size changes—which might or might not be a good thing.

Get Cascading Style Sheets: The Definitive Guide, Second Edition now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.