Compared to computers, printers are slow devices, and because they are commonly shared, it is generally undesirable for users to send jobs directly to them. Instead, most operating systems provide commands to send requests to a print daemon [2] that queues jobs for printing, and handles printer and queue management. Print commands can be handled quickly because printing is done in the background when the needed resources are available.

Printing support in Unix evolved into two camps with differing commands but equivalent functionality, as summarized in Table 4-2. Commercial Unix systems and GNU/Linux usually support both camps, whereas BSD systems offer only the Berkeley style. POSIX specifies only the lp command.

Here is an example of their use, first with the Berkeley style:

$lpr -Plcb102 sample.psSend PostScript file to print queue lcb102 $lpq -Plcb102Ask for print queue status lcb102 is ready and printing Rank Owner Job File(s) Total Size active jones 81352 sample.ps 122888346 bytes $lprm -Plcb102 81352Stop the presses! Kill that huge job

and then with the System V style:

$lp -d lcb102 sample.psSend PostScript file to print queue lcb102 request id is lcb102-81355 (1 file(s)) $lpstat -t lcb102Ask for print queue status printer lcb102 now printing lcb102-81355 $cancel lcb102-81355Whoops! Don't print that job!

lp and lpr can, of course, read input from standard input instead of from command-line files, so they are commonly used at the end of a pipeline.

System management can make a particular single queue the system

default so that queue names need not be supplied when the default is

acceptable. Individual users can set an environment variable, PRINTER (Berkeley) or

LPDEST (System V), to select a

personal default printer.

Print queue names are site-specific: a small site might

just name the queue printer, and make

it the default. Larger sites might pick names that reflect location,

such as a building abbreviation and room number, or that identify

particular printer models or capabilities, such as bw for a black-and-white printer and color for the expensive one.

Unfortunately, with modern networked intelligent printers, the lprm, cancel, lpq, and lpstat commands are much less useful than they once were: print jobs arrive quickly at the printer and appear to the printer daemon to have been printed already and are thus deleted from the print queue, even though the printer may still be holding them in memory or in a filesystem while other print jobs are still being processed. At that point, the only recourse is to use the printer's control panel to cancel an unwanted job.

Printer technology has changed a lot since Unix was first developed. The industry has moved from large impact printers and electric typewriters that formed characters by hammering a ribbon and paper against a metal character shape, to electrostatic, dot-matrix, inkjet, and laser printers that make characters from tiny dots.

Advances in microprocessors allowed the implementation inside the printer of simple command languages like Hewlett-Packard Printer Command Language (PCL) and HP Graphics Language(HPGL), and complete programming languagesânotably, Adobe PostScript. Adobe Portable Document Format (PDF) is a descendant of PostScript that is more compact, but not programmable. PDF offers additional features like color transparency, digital signatures, document-access control, encryption, enhanced data compression, and page independence. That last feature allows high-performance printers to rasterize pages in parallel, and PDF viewers to quickly display any requested page.

The newest generation of devices combines printing, copying, and scanning into a single system with a disk filesystem and network access, support for multiple page-description languages and graphics file formats, and, in at least one case, GNU/Linux as the embedded operating system.

Unfortunately, Unix printing software has not adapted rapidly enough to these improvements in printing technology, and command-level support for access to many features of newer printers remains poor. Two notable software projects attempt to remedy this situation: Common UNIX Printing System[3] (CUPS), and lpr next generation[4] (LPRng). Many large Unix sites have adopted one or the other; both provide familiar Unix printing commands, but with a lot more options. Both fully support printing of PostScript and PDF files: when necessary, they use the Aladdin or GNU ghostscript interpreter to convert such files to other formats needed by less-capable printers. CUPS also supports printing of assorted graphics image file formats, and n-up printing to place several reduced page images on a single sheet.

Despite its name, the venerable pr command does not print files, but rather, filters data in preparation for printing. In the simplest case, pr produces a page header timestamped with the file's modification time, or if input is from a pipe, with the current time, followed by the filename (empty for piped input) and a page number, with a fixed number (66) of lines per page. The intent was that:

pr file(s) | lpwould print nice listings. However, that simplicity has not worked since the old mechanical printers of the 1970s were retired. Default font sizes and line spacing vary between printers, and multiple paper sizes are in common use.

Instead, you generally have to experiment with setting the

output page length with the -l option, and often the

page width with the -w option and a text offset with

the -o option. It is also essential to add the

-f option (-F on some systems) to

output an ASCII formfeed control character at the start of every page

header after the first, to guarantee that each header starts a new

page. The reality is that you generally have to use something like

this:

pr -f -l60 -o10 -w65 file(s) | lpIf you use a different printer later, you may need to change those numeric parameters. This makes it hard to use pr reliably in portable shell scripts.

There is one feature of pr

that is often convenient: the -c

n option requests n-column

output. If you combine that with the -t option to

omit the page headers, you can produce nice multicolumn listings, such

as this example, which formats 26 words into five columns:

$ sed -n -e 19000,19025p /usr/dict/words | pr -c5 -t

reproach repugnant request reredos resemblant

reptile repulsion require rerouted resemble

reptilian repulsive requisite rerouting resent

republic reputation requisition rescind resentful

republican repute requited rescue reserpine

repudiateIf the column width is too small, pr silently truncates data to prevent column overlap. We can format the same 26 words into 10 (truncated) columns like this:

$ sed -n -e 19000,19025p /usr/dict/words | pr -c10 -t

reproa republ repugn reputa requir requit rerout rescue resemb resent

reptil republ repuls repute requis reredo rescin resemb resent reserp

reptil repudi repuls reques requis reroutpr has a lot of options, and historically, there was considerable variation among Unix systems in those options, and in the output format and number of lines per page. We recommend using the version from the GNU coreutils package, since it gives a uniform interface everywhere, and more options than most other versions. Consult the manual pages for pr(1) for the details.

Although some PostScript printers accept plain text, many do not. Typesetting systems like TEX and troff can turn marked-up documents into PostScript and/or PDF page images. If you have just a plain text file, how do you print it? The Unix printing system invokes suitable filters to do the conversion for you, but you then do not have any control over its appearance. The answer is text-to-PostScript filters like a2ps,[5] lptops,[6] or on Sun Solaris only, mp. Use them like this:

a2ps file > file.ps Make a PostScript listing of file a2ps file | lp Print a PostScript listing of file lptops file > file.ps Make a PostScript listing of file lptops file | lp Print a PostScript listing of file mp file > file.ps Make a PostScript listing of file mp file | lp Print a PostScript listing of file

All three have command-line options to choose the font, specify the typesize, supply or suppress page headers, and select multicolumn output.

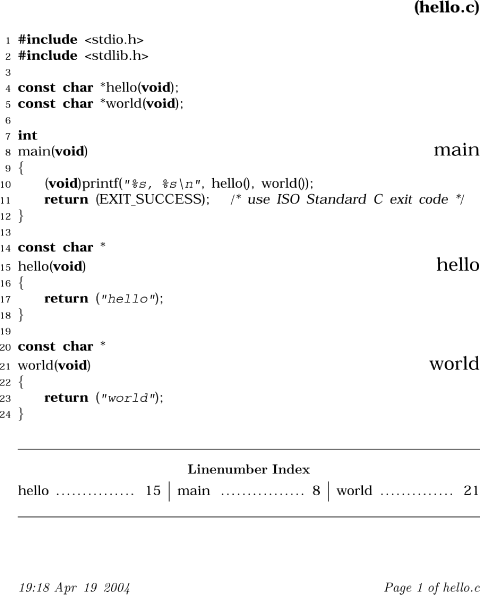

BSD, IBM AIX, and Sun Solaris systems have vgrind,[7] which filters files in a variety of programming languages, turning them into troff input, with comments in italics, keywords in bold, and the current function noted in the margin; that data is then typeset and output as PostScript. A derivative called tgrind [8] does a similar job, but with more font choices, line numbering, indexing, and support for many more programming languages. tgrind produces TEX input that readily leads to PostScript and PDF output. Figure 4-1 shows a sample of its output. Both programs are easy to use for printing of typeset program listings:

$tgrind -p hello.cTypeset and print hello.c $tgrind -i 1 -fn Bookman -p hello.cPrint the listing shown in Figure 4-1 $vgrind hello.c | lpTypeset and print hello.c

[2] A daemon (pronounced dee-mon) is a long-running process that provides a service, such as accounting, file access, login, network connection, printing, or time of day.

[3] Available at http://www.cups.org/ and documented in a book listed in the Chapter 16.

[4] Available at http://www.lprng.org/.

[5] Available at ftp://ftp.gnu.org/gnu/a2ps/.

[6] Available at http://www.math.utah.edu/pub/lptops/.

[7] Available at http://www.math.utah.edu/pub/vgrind/.

[8] Available at http://www.math.utah.edu/pub/tgrind/.

Get Classic Shell Scripting now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.