On occasion I am asked to take a static object and add motion to it so that it appears to be moving. You can add motion to objects in a couple of different ways. For instance, you might be asked to make a lateral motion, like when a car or person goes racing by. Motion could be added to make an object to appear as though it were spinning. Motion could also be added to make an object appear as though it is coming toward or traveling away from us. So how do we create motion where there was none?

Figure 4-16. Changing the shape of the mouth also means imagining what smiling will do to eyes, cheeks, etc.

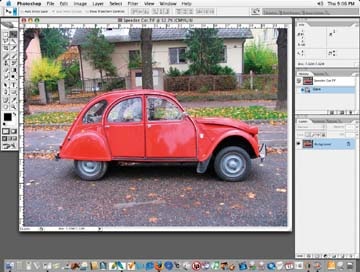

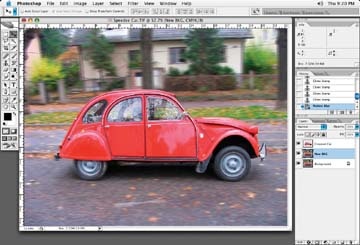

Adding motion to cars is typical request. This is often done because the client or manufacturer does not want to put excess mileage on to the vehicle or run the risk of damaging a new car. In this example, we'll take the car out of its stationary background and add motion to the background and the wheels. Figure 4-17 shows our sample vehicle standing perfectly still.

First, create a selection with the Pen tool. Make sure the selection is accurate by following the object exactly and by using as few points possible on your mask to keep it smooth and fluid. Depending on the how the rest of the image looks, I'll occasionally add a small degree of softness to the selection by choosing Select → Feather prior to isolating the vehicle. Once a selection of your object has been made, go to Layer → New → Layer via Copy to paste the selection on a new layer. Then give the new layer a descriptive name.

Once the vehicle is cropped and pasted on to a new layer, use the Clone brush to remove the vehicle or a good portion of it out from the original background. You don't have to get too fancy retouching the background, as you are going to blur it anyway, which will hide any brushing you may do. (Unless, of course, you're only going to blur the background to small degree; then brushing the car out of the background may be a little more critical.)

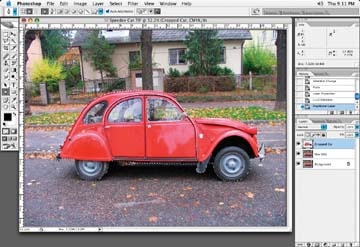

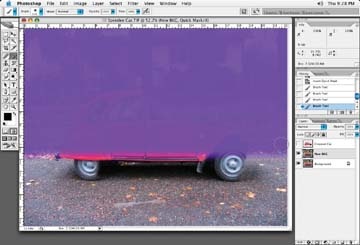

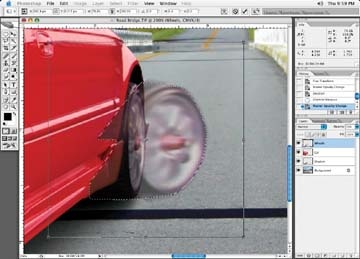

You should be left with cropped vehicle on a layer and an image that is the background with much of the car retouched out, particularly around the edges, as shown in Figure 4-18.

Figure 4-18. Our car is cropped out and pasted on to a new layer and a background layer with much of the car cropped out

Next, clone a portion of the car out of the background, because as you add motion blur to the background, the original car will blur as well and extend well outside of the original static car, if you clone some of it out. If I drop the cropped image of the car back onto a blurred background, the original car, if not airbrushed out, will be poking out around the edges because of the blur. The amount of image that has to be cloned out depends on how much blur is added. (The faster you want your car to go, the more blur should be added.) If the original car is not retouched out around the edges, when motion is added, ghosting will occur and bring the background car image through, an effect you can see in Figure 4-19. A car speeding forward would not have motion lines coming from the front of the car, unless it was rocking back and forth!

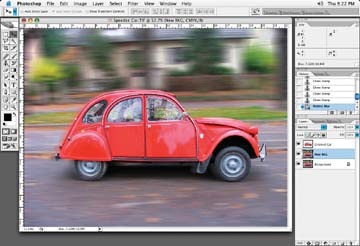

Once the car has been cloned a sufficient amount, you can create the motion blur. Start by selecting Filters → Blur → Motion Blur. Choose the angle of your blur carefully—it is important. The blur angle should match the angle of your object to appear natural. You do not want a blur that shoots off into space when the object is going from left to right, as in Figure 4-20!

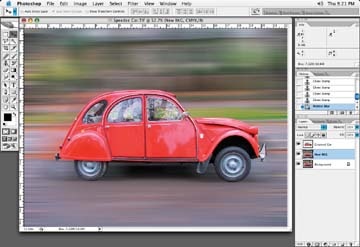

To avoid shooting your car off into space, set the motion blur angle to the same angle as the direction in which the car is traveling. You can judge this by setting the blur to match the two points between where the wheels of the car touch the ground. Figure 4-21 shows how the image appears after applying motion blur at the correct angle.

The amount of blur you choose is important, too. Some experimentation will be necessary. The faster you want your object to appear, the more blur you will want to add. Notice how much faster the car appears to be moving in Figure 4-22 than in Figure 4-23. Keep it real, though. Don't add a blur that makes the object appear as though it is traveling at 500 miles per hour when it is actually a person strolling down the street!

If you have an image with a reasonable amount of foreground and background, you can apply motion blur in two steps or use a vignetted mask. To do the blur in two steps, first add a motion blur you think would be suitable for the background of the image or the portion behind the main object. Then apply this blur to the overall image. Next, add more blur so that the foreground or the part of the image in front of the main object is blurred more than the background behind the main object. To put it in perspective, as a kid, did you ever hang your head out of your parents car window as it traveled down the highway to watch the speeding guardrail whiz by only to look up and see the horizon speed by much more slowly? OK, maybe it was just me, but hopefully you get the idea. What you are trying to create here is a fast moving foreground and a slower moving background or horizon.

Because the foreground is visually closer, the amount of blur will be more in the foreground. Add less to the background of the image the farther away it is. To accomplish this, make a mask of the background. Either make a very soft mask so the transition is very subtle, or if there is a harder object that is in foreground, like a guard rail, where it is suitable for separating the background and foreground, make the mask a little more defined.

You can create this type of motion in a couple of ways. One way would be to apply one motion blur overall that is suitable for the background, apply a second blur that is more suited to the foreground, take a History snapshot of the blur, and then paint it into only the foreground of your image. The History brush will be discussed in greater detail later on in this book.

The second way to accomplish this dual blurred effect is to create a selection or mask of the foreground and, by inverting the foreground mask, you'll have a selection for the background, and vice versa. In this way, two different blurs Figure 4-24. Using the Quick Mask function to display the Figure 4-25. The effect of the motion blur applied to the can be added to the background for a much more realistic look.

A third way would be to use the Quick Mask mode (Figure 4-24), select the Vignette tool from the Tool palette, and create a vignette that goes from the top to the bottom of your image. Once out of Quick Mask mode, make a selection through which you can blur the image. If you have made the vignette mask correctly, wherein the bottom part of your vignette mask has more color in it, then the bottom of the image will be affected more by the blur correction.

Next, go back to Picture mode and apply a motion blur to the back through the mask. The result should look like Figure 4-25.

The selection is inverted, and a smaller blur is added to the foreground. The only problem with this image is that no one is driving! I'll guess I'll have to fix up the windows so no one can see through them!

Typically, the car is what is "caught" with the camera, so the details of the car are sharp, or much sharper than the rest of the image. To finish this image, add a motion blur to the reflections in the windows (see the note) and a radial blur to the wheels and tires, technique we'll cover in the next section. Applying a motion blur in this fashion will make a blur more realistic.

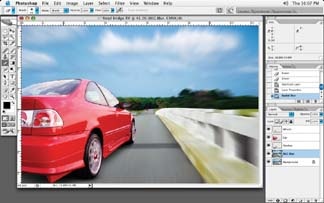

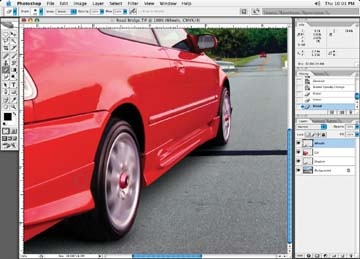

In this dramatic example, the red car sitting still in Figure 4-26 is going to be made to appear as though it is speeding past us and traveling to the road ahead (Figure 4-27).

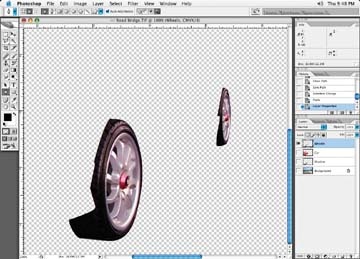

We'll begin by putting the wheels in motion with Photoshop's Radial Blur tool. The radial blur is designed to be used with a straight-on, perfect circle. So if the wheels are a straight-on shot, all you'll have to do is mask them, copy them, and paste them onto a new layer, using Layer → New → Layer Via Copy. (Make sure you get the tires as well. I have seen many people spin the wheel or hubcap, but forget the actual tire! If the wheels are on an angle, like they are in Figure 4-28, you'll have to make sure they are round before adding a radial bur.

To make the wheel and tire round, first make a selection of the two wheels and put them on a separate layer, as shown in Figure 4-28.

Next, select one of the wheels. Choose Edit → Transform → Scale and scale the wheel on the horizontal plane until you have what you feel is a round looking wheel. No need to measure it or use a compass on screen! Just make sure that it looks pretty round to you, like the one shown in Figure 4-29. Initially, it will look rather odd, of course, but not to worry—you will distort the wheel back to its original shape once you are done. Do one wheel at a time and repeat this process for each wheel.

An 18-wheel truck would take you quite a while!

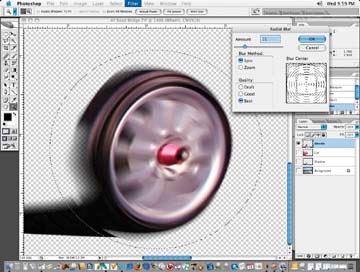

Once you've applied the Transform tool, repeat the transform process for the other wheel. Then make a circular selection around the wheel and apply a radial blur (Filter → Blur → Radial Blur)to the wheel, as shown in Figure 4-30.

Notice that the center of your wheel should match the center of the spin in the dialog box. You may have to try a couple of times to get the spin just right. If the spin is off center, the wheel spin will look off center, as it does in Figure 4-31.

Choose Spin and Best for your dialog options. You'll have to experiment with the amount of blur or spin to use. It may take a couple of goes before you see the amount of spin that you like. Obviously, the faster the object is traveling, the more spin you will want to choose.

Using the Transform tool Scale mode, bring the wheels back to their original shape on the horizontal plane only, just as you did to originally distort them. Basically, you are just trying to do the opposite of what you had done in the first place to distort the wheels to a round shape, only this time we are changing them back to the way they were originally. Typically, to bring the wheels back into the correct shape, I would set the opacity of the wheel layer to about 50% so that I can see the old wheel through my new spinning one, as in Figure 4-32. Then use the Transform tool in the Scale mode on the horizontal plane to adjust the shape of the wheel back to its original shape. Once done, I set the layer opacity back to 100%. This works for any wheel, regardless of the angle it was shot on.

The radial blur may cause some of the original wheel to overhang onto the body of the car. You will want to erase any of the wheel that may overhang onto the body of the car. Repeat this process for the second wheel. Typically, you can use the selection that you used to crop out the wheels from the original car as your guide to erasing the excess blur overhang of the wheels. The wheels are now complete you can see the results of this phase in Figure 4-33.

Time to add some motion to the background of the image. Let's call up the zoom blur option (Filter → Blur → Radial BlurZoom give the impression that we are speeding into the horizon. Adjust the center of the zoom blur to match the vanishing point of the horizon.

Now that we've got the wheels turning, let's add some motion to the background. A zoom blur option (Figure 4-34) is suitable when we are trying to make an object appear as though it is traveling away from or toward us. This differs from a motion blur, in that a motion blur is for objects traveling horizontally or vertically.

Select the background using one of the techniques described in the previous section. Within the Radial Blur dialog box, Choose Zoom as your Blur method. Again, make sure that the center or vanishing point, the point or the center where the object is disappearing into or heading toward, matches the center point in the Blur dialog box, as indicated in the Blur Center. Of course the amount of the blur will have to be experimented with. The more blur, the faster the object appears to be traveling.

So there you have it. Our car is on its way to wherever it's going. We've applied motion blur to the background. We've added motion to the wheels. Further motion could be added to the outside edge of the back of the car as if its paint isn't able to keep up with the rest of the vehicle! Adding a range of motion will be discussed in the following section.

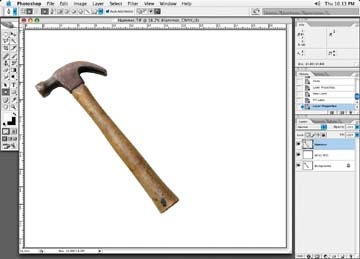

Sometimes clients want to give the impression that an image is moving, but show motion in such a way that it is stepped. The steps may show how many actions are required to use a tool, for instance. In the following example, I'll use the hammer shown in Figure 4-35 and show it moved through a range of motion.

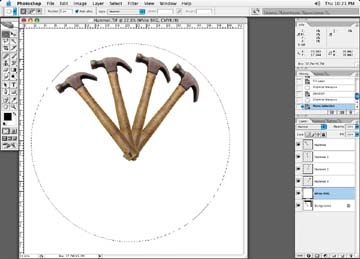

First, isolate the item to which you wish to add motion; in this case, select the hammer so that it is a separate element. Once you have it isolated, paste the hammer on to a new layer, and duplicate this layer depending on how many steps you would like to have. In this case, there will be three steps, so I'll make three duplicate layers.

Next, use the Transform tool to rotate each of the hammers. Make sure that you set the pivot point of the rotation to the correct pivot point of the image. The pivot point is the little crosshair that appears in the center of your image when you select the Transform tool. In this case, the center of the hand or wrist position will be the pivot point from which the hammer rotated. Click on the little pivot point crosshair and move it to the hand position, as shown in Figure 4-36.

Figure 4-36. We will want all hammers to pivot from the same pivot point so they all appear to be the same hammer

Once the pivot point is established, space out the duplicate images to show a range of motion, as in Figure 4-37.

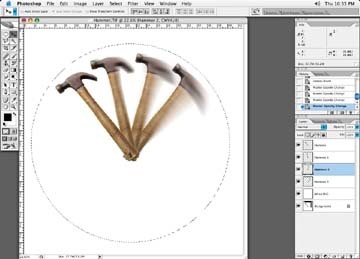

Next, we will go to each duplicate layer and add motion. Since the hammer is swinging in a circular motion, we'll use a radial blur. Make a large circular selection, trying to make your pivot point the center of your circular selection, as in Figure 4-38. You may need to adjust the canvas size. Just as our wheel images in the earlier example required an accurate center point, the same is true for these hammer images. You want the center of your spin to originate from the pivot point.

Call up the Radial Blur dialog box and apply a blur. You may have to try different settings based on the size of the image and the amount of motion you are looking for. Start with a blur amount of 10 or 20, and work your way on from there. Choose Spin as your blur type and the quality of Good. (You may want to choose draft mode if you are experimenting with a very large image to save some processing time. Then, when you see a setting you like, redo the blur in the Good or Best mode.)

Keep in mind that you will have to repeat the blur for each hammer layer; in this case, you'll have to apply the radial blur to three of the hammers. The hammer to the far left is our final stopped hammer, so a blur isn't required for it. Quite honestly, I usually use the good mode as it is a spin and blurry, and that in itself hides any imperfections and saves you some time over using the best mode. Ultimately, the amount of the blur effect is determined by the size and resolution of the image. A blur amount of 20 on a postcard-sized image may be too much, but on a movie poster, it may not even be all that noticeable.

Once you are happy with the motion and it has been applied, take a History snapshot of the motion you have applied, and then undo the change so that you are back to the original state of the image. Using the History brush, select the appropriate snapshot, and then brush the motion effect to the one side of the hammer in motion. Since the hammer is swinging to the left from the right, add your motion to the right of the hammer. Motion is always added to the opposite side of the direction the object is traveling to. By adding motion to just one side of the object, as in Figure 4-39, it will appear as though the hammer is traveling in one direction.

Note

You wouldn't add motion to the front of an object, as it hasn't "been there yet." If you did add motion to the front of an image as well, it would appear to be rocking back and forth.

Repeat this process for all duplicate images. Once that is complete, change the opacity of each duplicate layer. You may want to start off with 25% opacity for the first image, the one farthest from the main image of the hammer, and work your way through the layers progressively. The next layer could be 50%, then 75%, and finally the main image at 100%. Of course, these layer opacity values are only a starting point, and some experimentation may be in order.

Figure 4-39. Add progressively less blur as the hammer gets closer to the first hammer on the far left to give the impression the hammer is coming to a stop or striking something like a nail

The purpose of the varying opacity percentages is to give the impression that the object is traveling in a set motion range. The lightest layer that is farthest away from the actual hammer is fading away as the hammer travels through its range of motion. You can see the final effect in Figure 4-40.

Get Commercial Photoshop Retouching: In the Studio now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.