Children inherit traits from their parents—eye color, height, male-pattern baldness, and so on. Sometimes we inherit traits from more distant ancestors, like grandparents or great-grandparents. As you saw in the previous chapter, the metaphor of family relations is part of the structure of HTML as well. And just like humans, HTML tags can inherit CSS properties from their ancestors.

Inheritance is the process by which some CSS properties applied to one tag are passed on to nested tags. For example, a <p> tag is always nested inside of the <body> tag, so properties applied to the <body> tag get inherited by the <p> tag. Say you created a type selector style (Creating an External Style Sheet) for the <body> tag that sets the color property to a dark red. Tags that are descendants of the <body> tag—that is, the ones inside the <body> tag—will inherit that color property. That means that any text in those tags —<h1>, <h2>, <p>, or whatever—will appear in that same dark red color.

Inheritance works through multiple generations as well. If a tag like the <em> or <strong> tag appears inside of a <p> tag, then the <em> and the <strong> tags also inherit properties from any style applied to the <body> tag.

Note

As discussed in Chapter 3, any tag inside of another tag is a descendant of that tag. So a <p> tag inside the <body> tag is a descendant of the <body>, while the <body> tag is an ancestor of the <p> tag. Descendants (think kids and grandchildren) inherit properties from ancestors (think parents and grandparents).

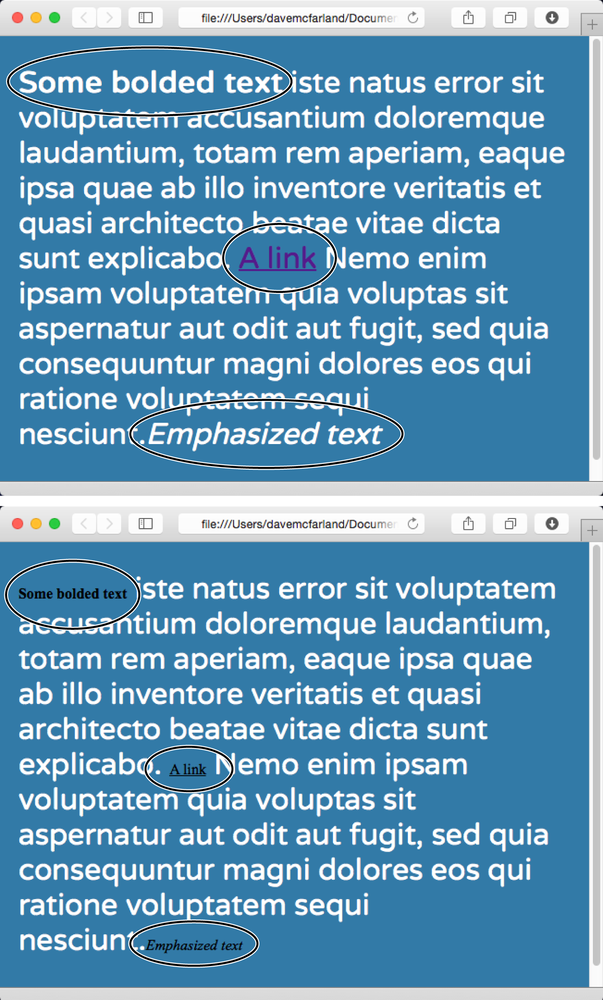

Although this may sound confusing, inheritance is a really big timesaver. Imagine if no properties were passed onto nested tags and you had a paragraph that contained other tags like a <strong> tag, an <em> tag to emphasize text and an <a> tag to add a link. If you created a style that made the paragraph text white and 32 pixels tall, using the Varela Round font, it would be weird if all the text inside the <em>, <strong> and <a> tags reverted to its regular, “browser boring” style (see Figure 4-1). You’d then have to create another style to format the <em> tag to match the appearance of the <p> tag. What a drag.

Inheritance doesn’t just apply to tag styles. It works with any type of style, so when you apply a class style (see Class Selectors: Pinpoint Control) to a tag, any tags inside that tag inherit properties from the styled tag. The same holds true for ID styles, descendant selectors, and the other types of styles discussed in Chapter 3.

You can use inheritance to your advantage to streamline your style sheets. Say you want all the text on a page to use the same font. Instead of creating styles for each tag, simply create a tag style for the <body> tag. (Or create a class style and apply it to the <body> tag.) In the style, specify the font you wish to use, and all of the tags on the page inherit the font:

body {

font-family: Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif;

}You can also use inheritance to apply style properties to a section of a page. For example, like many web designers, you may use the <div> tag (ID Selectors: Specific Page Elements) to define an area of a page like a banner, sidebar, or footer; or if you’re using HTML5 elements, you might use one of the sectioning elements like <header>, <aside>, <footer>, or <article>. By applying a style to that outer tag, you can specify particular CSS properties for all of the tags inside just that section of the page. If you want all the text in a sidebar to be the same color, you’d create a style setting the color property, and then apply it to the <div>, <header>, <article>, or other sectioning element. Any <p>, <h1>, or other tags inside inherit the same font color.

Figure 4-1. Inheritance lets tags copy properties from the tags that surround them. Top: The paragraph tag is set with a specific font family, size, and color. The tags inside each paragraph—the <strong>, <a>, and <em> tags circled—inherit those properties so they look like the rest of the paragraph. Bottom: If inheritance didn’t exist, the same page would look like this figure. Notice how the <strong>, <em>, and <a> tags inside the paragraph (circled) retain the font-family, size, and color defined by the browser. To make them look like the rest of the paragraph, you’d have to create additional styles—a big waste of time.

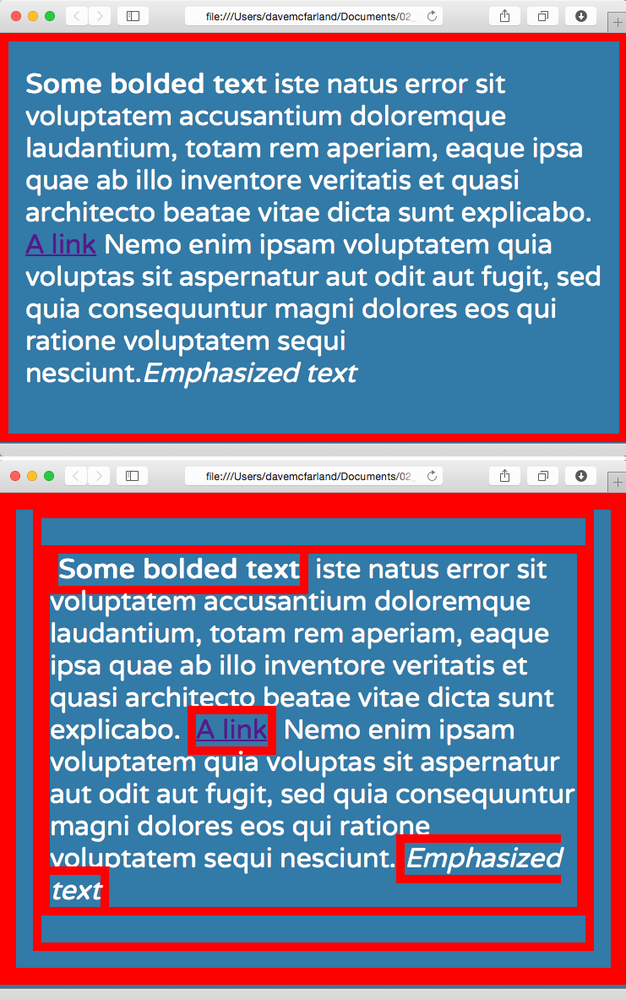

Inheritance isn’t all-powerful. Many CSS properties don’t pass down to descendant tags at all. For example, the border property (which lets you draw a box around an element) isn’t inherited, and with good reason. If it were, then every tag inside an element with the border property would also have a border around it. For example, if you added a border to the <body> tag, then every bulleted list would also have a box around it, and each bulleted item in the list would also have a border (Figure 4-2).

Note

There’s a list of CSS properties in Appendix A, including details on which ones get inherited.

Here are examples of times when inheritance doesn’t strictly apply:

As a general rule, properties that affect the placement of elements on the page or the margins, background colors, and borders of elements aren’t inherited.

Web browsers use their own inherent styles to format various tags: Headings are big and bold, links are blue, and so on. When you define a font size for the text on a page and apply it to the

<body>tag, headings still appear larger than paragraphs, and<h1>tags are still larger than<h2>tags. It’s the same when you apply a font color to the<body>; the links on the page still appear in good old-fashioned web-browser blue.Note

It’s usually a good idea to eliminate these built-in browser styles—it’ll make designing sites that work consistently among different browsers easier. In Chapter 5, on Starting with a Clean Slate, you’ll learn how to do that.

When styles conflict, the more specific style wins out. In other words, when you’ve specifically applied CSS properties to an element—like specifying the font size for an unordered list—and those properties conflict with any inherited properties—like a

font-sizeset for the<body>tag—the browser uses the font size applied to the<ul>tag.

Note

These types of conflicts between styles are very common, and the rules for how a browser deals with them are called the cascade. You’ll learn about that in Chapter 5.

Figure 4-2. Fortunately, not all properties are inherited. The border applied to the body of this page (the thick red outline around the content) in the image at top isn’t inherited by the tags inside the body. If they were, you’d end up with an unattractive mess of boxes within boxes within boxes (bottom).

In this three-part tutorial, you’ll see how inheritance works. First, you’ll create a simple tag selector and watch it pass its characteristics on to nested tags. Then, you’ll create a class style that uses inheritance to alter the formatting of an entire page. Finally, you’ll see where CSS makes some welcome exceptions to the inheritance rule.

To get started, you need to download the tutorial files located at https://github.com/sawmac/css_mm_4e. Click the tutorial link and download the files. All of the files are enclosed in a zip archive, so you’ll need to unzip them first. (Detailed instructions for unzipping the files are on the website.) The files for this tutorial are contained in the folder named 04.

To see how inheritance works, start by adding a single tag style and see how it affects the tags nested inside. The next two parts of this tutorial will build upon your work here, so save the file when you’re done.

Open the file inheritance.html in your favorite text editor.

This file already has an internal style sheet, with one type selector giving the

<body>tag a background color.Note

In general, it’s better to use external style sheets for a website, for reasons discussed in Chapter 2 (External Style Sheets). But for a simple tutorial like this, it’s easier to just work with one file.

Add another style after the

<body>style in the style sheet:p { color: rgb(92,122,142); }As you’ve seen in the previous tutorials, the

colorproperty sets the color of text. Your style sheet is complete.Open the page in a web browser to preview your work.

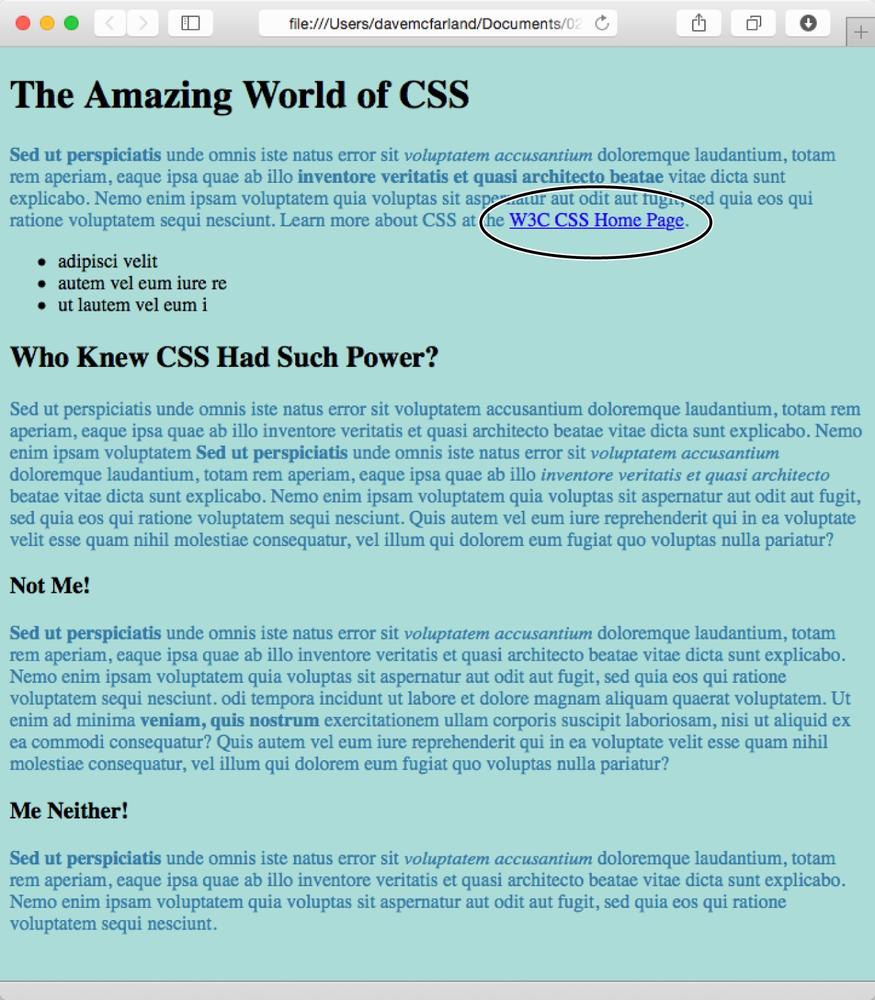

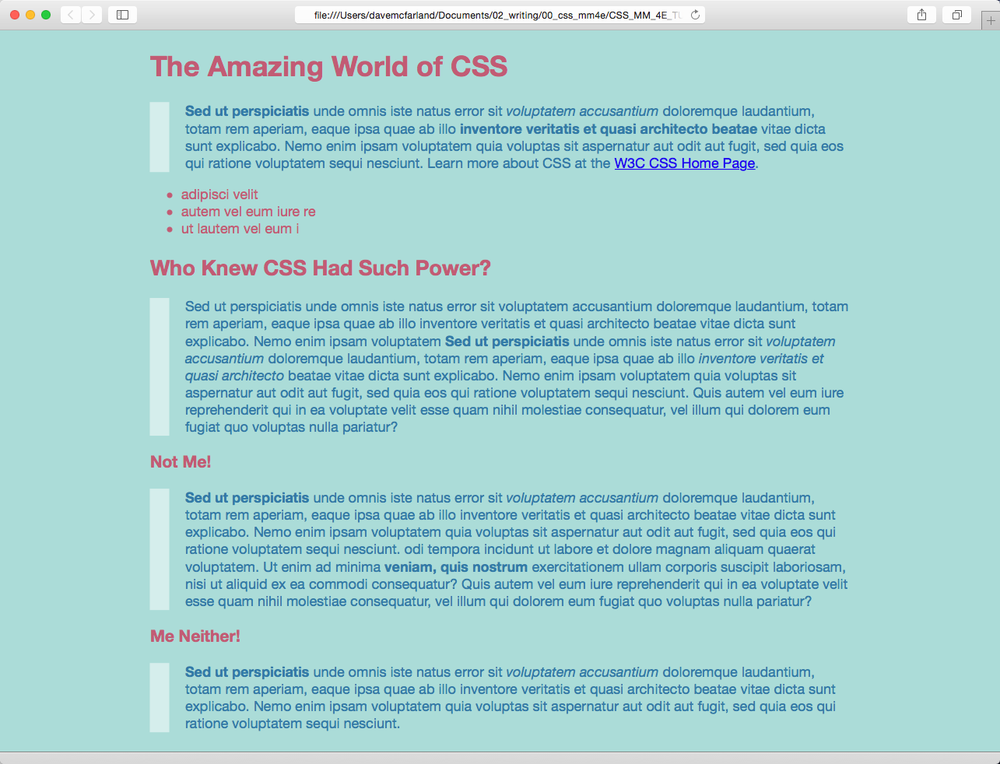

The color of the page’s four paragraphs has changed from black to a slate blue color (see Figure 4-3).

But notice how this <p> tag style affects other tags: Tags inside of the <p> tag also change color. For example, the text inside the <em> and <strong> tags inside each paragraph also changes from black to slate blue while maintaining its italic and bold formatting. This kind of behavior makes a lot of sense. After all, when you set the color of text in a paragraph, you expect all the text in the paragraph—regardless of any other tags inside that paragraph—to be the same color.

Without inheritance, creating style sheets would be very labor intensive. If the <em> and <strong> tags didn’t inherit the color property from the <p> tag selector, then you’d have to create additional styles—perhaps descendant selectors like p em and p strong—to correctly format the text.

However, you’ll notice that the link at the end of the first paragraph doesn’t change color—it retains its link-blue color. As you’ll learn on Starting with a Clean Slate, browsers have their own styles for certain elements, so inheritance doesn’t apply. You’ll learn more about this behavior in Chapter 5.

Inheritance works with class styles as well—any tag with any kind of style applied to it passes CSS properties to its descendants. With that in mind, you can use inheritance to make quick, sweeping changes to an entire page.

Return to your text editor and the inheritance.html file.

You’ll add a new style below the

<p>tag style you created.Click at the end of the closing brace of the

pselector. Press Enter to create a new line, and then type.content {. Hit Enter twice, and type the closing brace:}.You’re about to create a new class style that you’ll apply to the

<body>tag, which surrounds the other tags on this page.Click between the two braces, and then add the following list of properties to the style:

font-family: "Helvetica Neue", Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif; font-size: 18px; color: rgb(194,91,116); max-width: 900px; margin: 0 auto;

The whole thing should look like this:

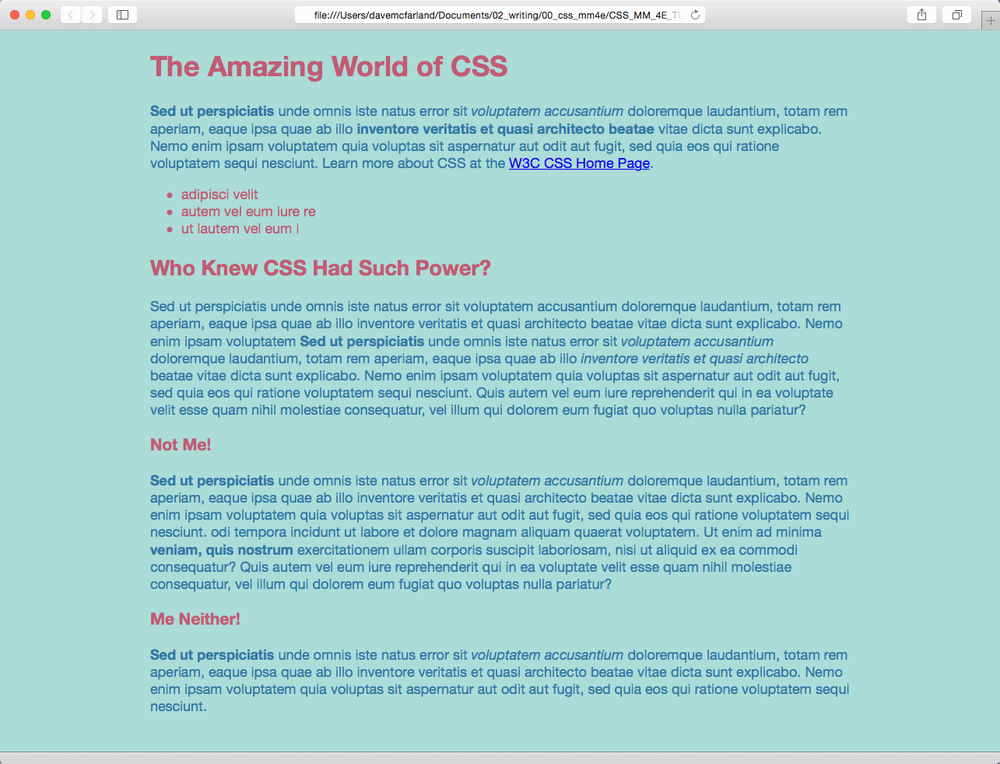

.content { font-family: "Helvetica Neue", Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif; font-size: 18px; color: rgb(194,91,116); max-width: 900px; margin: 0 auto; }This completed class style sets a font, font size, and color. It also sets a width and centers the style on the page (you saw this trick in the previous tutorial on Finishing Touches for creating a fixed, centered area for a page’s content).

Find the opening

<body>tag (just below the closing</head>tag), and then typeclass=“content”.The tag should now look like this:

<body class=“content”>. It applies the class to the<body>tag. Thanks to inheritance, all tags inside of the<body>tag (which are also all the tags visible inside a browser window) inherit this style’s properties and therefore use the same font.Save and preview the web page in a browser.

As you can see in Figure 4-4, your class style has created a seamless, consistent appearance throughout all text in the body of the page. Both headings and paragraphs inside the

<body>tag have taken on the new font styling.

The page as a whole looks great, but now look more closely: The color change affected only the headings and the bulleted list on the page, and even though the style specified an exact font size, the headline text is a different size than the paragraphs. How did CSS know that you didn’t want your headings to be the same 18-pixel size as the body text? And why didn’t the nested <p> tags inherit your new color styling from the <body> tag?

Note

Why use a class—content—instead of a tag style—body—to redefine the look of the page? Well, in this case, a tag style would work fine. But applying a class to the <body> tag is a great way to customize the look of different pages on your site. For example, if all pages on your site share the same external style sheet, a body tag style would apply to the <body> tag of every page on your site. By creating different classes (or IDs) you can create a different style for the <body> tag for different sections of the site or different types of pages.

You’re seeing the “cascading” aspect of Cascading Style Sheets in action. In this example, your <p> tags have two color styles in conflict—the <p> tag style you created in step 2 on Tutorial: Inheritance and the class style you created here. When styles collide, the browser has to pick one. As discussed on Creating a Descendant Selector, the browser uses the more specific styling—the color you assigned explicitly to the <p> tag. You’ll learn much more about the rules of the cascade in Chapter 5.

Inheritance doesn’t always apply, and that isn’t necessarily a bad thing. For some properties, inheritance would have a negative effect on a page’s appearance. You’ll see another example of inheritance in action in the final section of this tutorial. Margins, padding, and borders (among other properties) don’t get inherited by descendant tags—and you wouldn’t want them to, as you’ll see in this example.

Return to your text editor and the inheritance.html file.

You’ll expand on the

ptag style you just created.Locate the

pstyle, click at the end of the color property(color: rgb(50,122,167);), and then press Enter (Return) to create a new line.You’ll indent the paragraphs on the page by adding a left margin.

Add two properties to the style so it looks like this:

p { color: rgb(50,122,167);padding-left: 20px;border-left: solid 25px rgba(255,255,255,.5);}These changes add a border to the left side of every paragraph, and move the text so that it doesn’t touch the border: The

paddingproperty indents the paragraph text 20 pixels from the border.Save the file and preview it in a web browser.

Notice that all of the

<p>tags have a thick light border on the left. However, the tags inside the<p>tag (for example, the<em>tag) don’t have any additional indentation or border (see Figure 4-5). This behavior makes sense: It would look weird if there were an additional thick border and 20px of space to the left of each<em>and each<strong>tag inside of a paragraph!To see what would happen if those properties were inherited, edit the

pselector so that it looks like this:p, p *, which makes it into a group selector (Styling Groups of Tags). The first part is just thepselector you already created. The second part—p *—means “select all tags inside of a<p>tag and apply this style to them.” (The *, or universal selector, is described on Styling Groups of Tags.)

Get CSS: The Missing Manual, 4th Edition now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.