Chapter 1. Essentials of Modeling and Microtargeting

Dan Castleman is cofounder and Director of Analytics at Clarity Campaign Labs, a modeling and targeting consulting firm for progressive candidates, political coalitions, corporations, international campaigns, and charitable groups. His expertise covers strategic program targeting, data analysis, modeling, and polling. One of the leading modelers in Democratic politics, Castleman has built voter targeting models for the Democratic National Committee, Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee, and Democratic Governors’ Association, as well as dozens of individual campaigns and advocacy groups.

In the Democratic Party today, modeling and microtargeting have become ubiquitous. They are no longer peculiar curiosities confined to only a few forward-thinking campaigns, but de facto parts of any modern campaign with sufficient resources. While this leap forward can at least partly be attributed to coverage of their use by the Obama campaign in 2012, individual-level models have been used by Democratic campaigns since as early as 2004. Indeed, in many ways modeling and microtargeting are simply an extension of tactics employed to target voters at the aggregate level for decades. Over the past ten years, I have built countless models and advised dozens of political campaigns in how to use them. In that time, I have seen firsthand their rise in use, what they can (and can’t) do, and what methods for building them work the best.

Although the two terms are often used interchangeably, “modeling” and “microtargeting” have some important distinctions. Modeling is the practice of using algorithms and observed data to build statistical or machine learning models, in order to predict unobserved actions or preferences. Modeling for political campaigns is most often done at the individual level using voter files, which combine official voter registration lists with other data sources, such as consumer records, campaign contact histories, and other proprietary information collected by the campaign and party.

Microtargeting, meanwhile, refers to the process of making campaign targeting decisions at the individual level—for instance, selecting which voters to mail campaign literature to—and is generally informed by these voter models. While these practices are clearly intertwined, they are not inseparable. Modeling can still be done on other types of data (e.g., collections of exit polls or precinct-level vote totals), and microtargeting can be done in the absence of models (e.g., making selections based on characteristics included in voter files or consumer data).

What Models Can and Cannot Do

The practice of using models and microtargeting has made a profound and important impact on how campaigns are run. But despite what is often said and written about them, they do not offer unpopular politicians any magic ability to win over electorates that dislike them. And while they can provide an accurate snapshot of the electorate’s overall preferences, they are not an efficient way to generate the horse-race numbers that the media and public are most interested in. What they can do—and what we ultimately seek most from them—is to improve the efficiency of how campaigns run their programs.

While efficiency sounds like a rather mundane goal, for political campaigns it is of the utmost importance. Campaigns have to gain the support of a majority of often-large electorates, but are constrained in terms of money, volunteers, and the ever-looming election date. To help use these limited resources as wisely as possible, campaigns have to be smart about how they target voters. For example, looking at the breakdown of survey responses across subgroups can give a campaign an idea of the types of voters who are potential supporters or areas where a candidate’s popularity is weak. The same can be done historically by examining past election results at the precinct level. Modeling allows us to apply a more robust methodology to identify targets and provides even greater efficiency gains when applied at the individual level.

Selecting Voters to Target

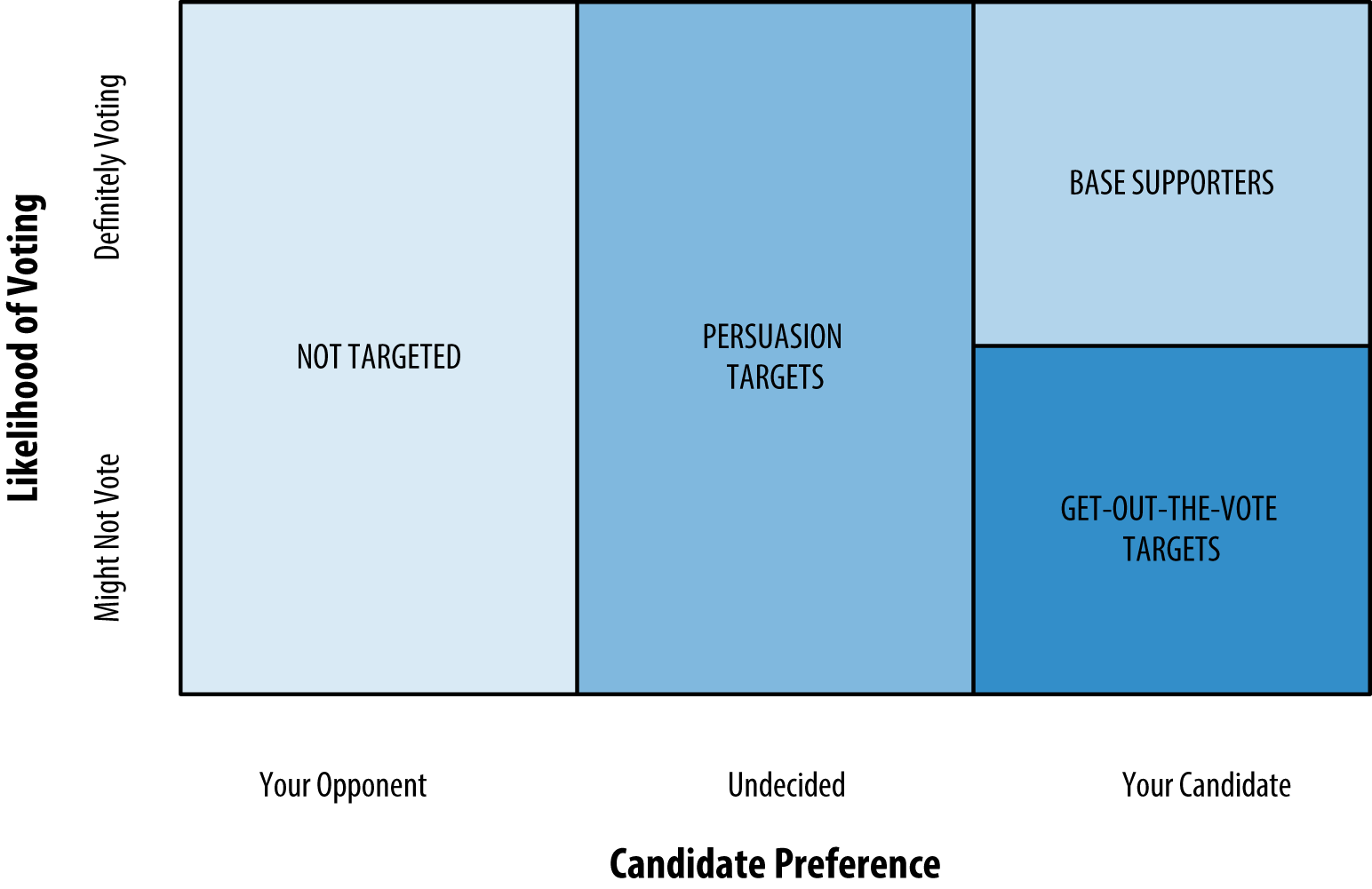

Since campaigns’ targeting needs drive their modeling needs, decisions about what models to build are based on larger strategic assumptions. When developing their overall strategies, campaigns typically think about voters in two main dimensions: support for their candidate and likelihood of voting. For campaigns it is not just important to identify whom voters support and whether they are persuadable, but also whether or not they will take their support to the polls. Figure 1-1 demonstrates how these two measures are connected and further divides voters into the three groups on which campaigns will want to focus their resources.

Figure 1-1. Basics of voter targeting in campaigns

When targeting voters who are highly likely to turn out and support their candidate (“base supporters”), campaigns will seek financial contributions and recruit volunteers. Those with high support but uncertain likelihood of voting become targets for “get-out-the-vote” efforts to increase their turnout. And those with uncertain support will be targeted for persuasion. For the remaining voters—those highly likely to support the opponent—a campaign’s limited resources are best spent elsewhere, as these voters are not very likely to respond to the campaign’s efforts.

This strategic thinking explains why turnout and support scores are the most common (and in many cases, the most useful) models for campaigns, but there are many other types of models that can also be valuable for campaigns. Table 1 lists some of the most common types of voter models, many of which are available pre-built and scored nationally by firms like Clarity.

| Type of Score | Description |

|---|---|

|

Party |

Likelihood of identifying with one political party or another |

|

Turnout |

Likelihood of voting in a given election |

|

Candidate Support |

Likelihood of supporting a specific candidate |

|

Issue Position |

Likelihood of holding a given position on a specific issue (marriage equality, gun control, etc.) |

|

Volunteer / Donation Propensity |

Likelihood of being a campaign activist or donor |

|

Demographic / Behavioral |

Likelihood of being a college graduate, gun owner, Fox News watcher, etc. |

|

Persuasion |

Likelihood of being responsive to campaign persuasion |

How Models Are Made

Most models are built using survey data—and lots of it.1 For example, a candidate support model will be informed by a short survey with a large sample size. Unlike traditional “horse-race” election polls (like those put out by newspapers and TV networks), which usually include between 400 and 1,000 responses, modeling surveys typically use anywhere from 2,500 to 20,000 or more responses, depending on the size of the geography and the type of model. A support model can be built on something as simple as a head-to-head candidate support question, and the responses used directly as the model’s outcome. For more complex characteristics, such as a voter’s persuadability, models may use multiple questions in aggregate or estimate treatment effects from randomized experimental tests.

The end result of most models is a “score” that we can append to the voter file used by the campaign for targeting. Most scores represent estimated probabilities (of supporting a candidate or turning out to vote, for example), but others may give percentile or decile rankings, especially for outcomes that are unlikely to be well calibrated (often because they are built on low-frequency events, such as volunteering or donation).

As mentioned before, models are not magic. They can help find persuadable voters, but they cannot make voters persuadable or make a poor message more effective. And while the models we build get increasingly accurate every year, they will always be probabilistic, which means they will always have some degree of error. For example, appended consumer records can improve models, but they are far less informative than you might think: the data points provided are often sparse, vaguely sourced, or just plain wrong.

This uncertainty affects the methods and algorithms we use. With hundreds or thousands of potential features to include, the most important step in modeling is often the feature selection process. Furthermore, the machine learning algorithms that work the best for our needs are ones that scale well with a large number of disparate features and can discover nonlinear patterns. Tree-based models are most common, particularly as ensembles of trees (such as random forests) or when ensembled with other types of models. But every campaign’s needs are different, and even more rudimentary algorithms, such as linear and logistic regressions, are still used for certain models.

Like much of the data science community, the political modeling field is increasingly turning to open-source tools such as R and Python, although some practitioners use commercial packages like Stata. In addition to developing a community of data scientists with expertise with these tools, we have also invested resources in building systems that allow us to work with large datasets efficiently and quickly, in order to create and score models in a streamlined fashion. These systems combine custom ETL and analytics tools with terabyte-scale data warehouses of voter data, allowing us to update models frequently so that the already-short timelines of campaigns are not held up by our processes. After all, our models are only useful to a campaign if they have time to employ them, so efficient turnaround is key to providing value.

Looking ahead, there are still new techniques to be explored, methodologies to be improved, and challenges to overcome. For example, we have been working on enhancing our methods for providing accurate and useful models for not just presidential and statewide campaigns but for smaller campaigns as well (such as those for state legislature or local offices). To help these downballot campaigns in 2016, the Democratic National Committee has put together a suite of “off the shelf” models available to all their campaigns nationwide, and we at Clarity have been working on finding ways for multiple smaller campaigns to pool their resources and develop customized models that wouldn’t otherwise be affordable or feasible. In this unusual election cycle, we are constantly striving to improve, adapt, and understand the implications of the ever-changing political winds on modeling for all races up and down the ticket.

1 Turnout models are the most notable exception: the standard approach is simply to model turnout in comparable past elections (as recorded in official voter files) to make inferences about who is most likely to turn out in the next election. Other models, such as those for donation or volunteer propensity, can also be built on similar directly observed behaviors.

Get Data and Democracy now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.