Introduction

Engineering is easy. People are hard.

Bill Coughran,

former senior vice president of engineering at Google

Life is full of unexpected twists, and the two of us never imagined we’d someday write a book about teamwork and collaboration.

Like so many modern “makers,” we discovered that our hobby and passion—playing with computers—was a great way to make a living after graduating college. And like most hackers of our generation, we spent the mid-1990s building PCs out of spare parts, installing prerelease versions of Linux from piles of diskettes, and learning to administer Unix machines. At the dawn of the dot-com bubble we became programmers, and after the bubble burst we started working for surviving Silicon Valley companies such as Apple. Later, we were hired by a startup to work full time on designing and writing an open source version control system called Subversion.

But something unexpected happened between 2000 and 2005. While we were creating Subversion, our job responsibilities slowly changed. We weren’t just writing code all day in a vacuum; we were leading an open source project. This meant hanging in a chat room all day with a dozen other volunteer programmers and paying attention to what they were doing. It meant coordinating new features almost entirely through an email list. Along the way, we discovered that the key to a project’s success wasn’t just writing great code: the way in which people collaborated toward the end goal mattered just as much.

In 2005 we started Google’s Chicago engineering office and continued our careers as programmers. At this point we were already deeply involved with the open source world—not just Subversion, but the Apache Software Foundation (ASF) too. We ported Subversion to Google’s BigTable infrastructure and launched an open source project hosting service (similar to SourceForge) under the banner of Google Code. We began attending—then speaking at—developer-centric conferences such as OSCON, ApacheCon, PyCon, and eventually Google I/O. We discovered that by working in both corporations and open source projects we had accidentally picked up a trove of wisdom and anecdotes about how real software engineering teams work. What began as a series of humorous talks about dysfunctional development processes (“Subversion Worst Practices”) eventually turned into talks about protecting teams from jerks (“How Open Source Projects Survive Poisonous People”). Larger and larger crowds gathered at our presentations in what can only be described as “group therapy” for software developers.

After giving talk after talk about the social challenges of creative collaboration, our editor at O’Reilly Media encouraged us to convert the talks into a book. The rest is history.

Who Is This Book For?

This book was originally written for software developers—for those who are trying to advance their careers and ship great software. But in updating the book for a second edition, it has become clear to us that the topics in this book apply to a much broader group. If you work on any sort of creative endeavor with other people, the lessons in this book apply to you. You might be part of a neighborhood club, a church group, a fraternity, a committee, or a group of architects. We’re assuming two important things about you as our reader:

-

You work on a team with other creative people, probably in a corporate or other structured environment.

-

You enjoy building things and believe it should be a rewarding and fun activity. If you’re cranking out products for no other reason than to pay your bills, you probably aren’t interested in self-actualization or career fulfillment.

Our own experiences come from software engineering, so predictably most of the examples in this book live in that realm. But nearly all the processes and strategies we describe are directly applicable (or have a direct analogue) to any team of creative people.

In the process of discussing how engineers best “play well with others,” we end up touching on a number of subjects that (superficially) may seem to be out of a programmer’s job description. At different points we discuss how to lead a team effectively, navigate an organization, and build a healthy relationship with the users of your software. On the surface these chapters may seem specifically directed toward “people managers” or “product managers”—but we assure you that at some point in your career you’ll find yourself accidentally wearing those hats. Suspend your disbelief and keep reading! Everything in this book is ultimately relevant to anyone building things.

Warning: This Is Not a Technical Manual

Before we start, we need to set your expectations. Motivated programmers love to read books that lay out domain-specific problems in a perfect mathematical presentation; each problem is typically paired with a prescribed procedural solution.

This is not such a book.

Our book specifically investigates the human side of creative product development, and humans are complex things. As we like to say in our talks, “People are basically a giant pile of intermittent bugs.” Both the problems and solutions we discuss are messy and difficult to place into perfect logical boxes. This book reads as a series of essays, because that’s what it essentially is. In each chapter we’ll discuss a slew of related problems (often as anecdotes), then move on to discuss a group of solutions relevant to the overall topic. To fully absorb everything you may need to lengthen your attention span to cover multiple pages, engage your right brain to make connections, or just plain sleep on it!

We should also make a couple more disclaimers. As we like to joke in our talks, “These opinions are purely our own and are based on our experiences. If you disagree, you’re welcome to get your own talk.” Just as with our oral presentations, we encourage any and all discussion that arises from the topics in this book. We’re happy to chat about feedback, corrections, new opinions, and disagreements: you can find us at http://www.debuggingteams.com/. Everything in this book comes from our own trials by fire and the lessons that came out of our numerous mistakes.

You should also know that every name used in our examples has been changed to protect the innocent (or guilty).

The Contents of This Book Are Not Taught in School

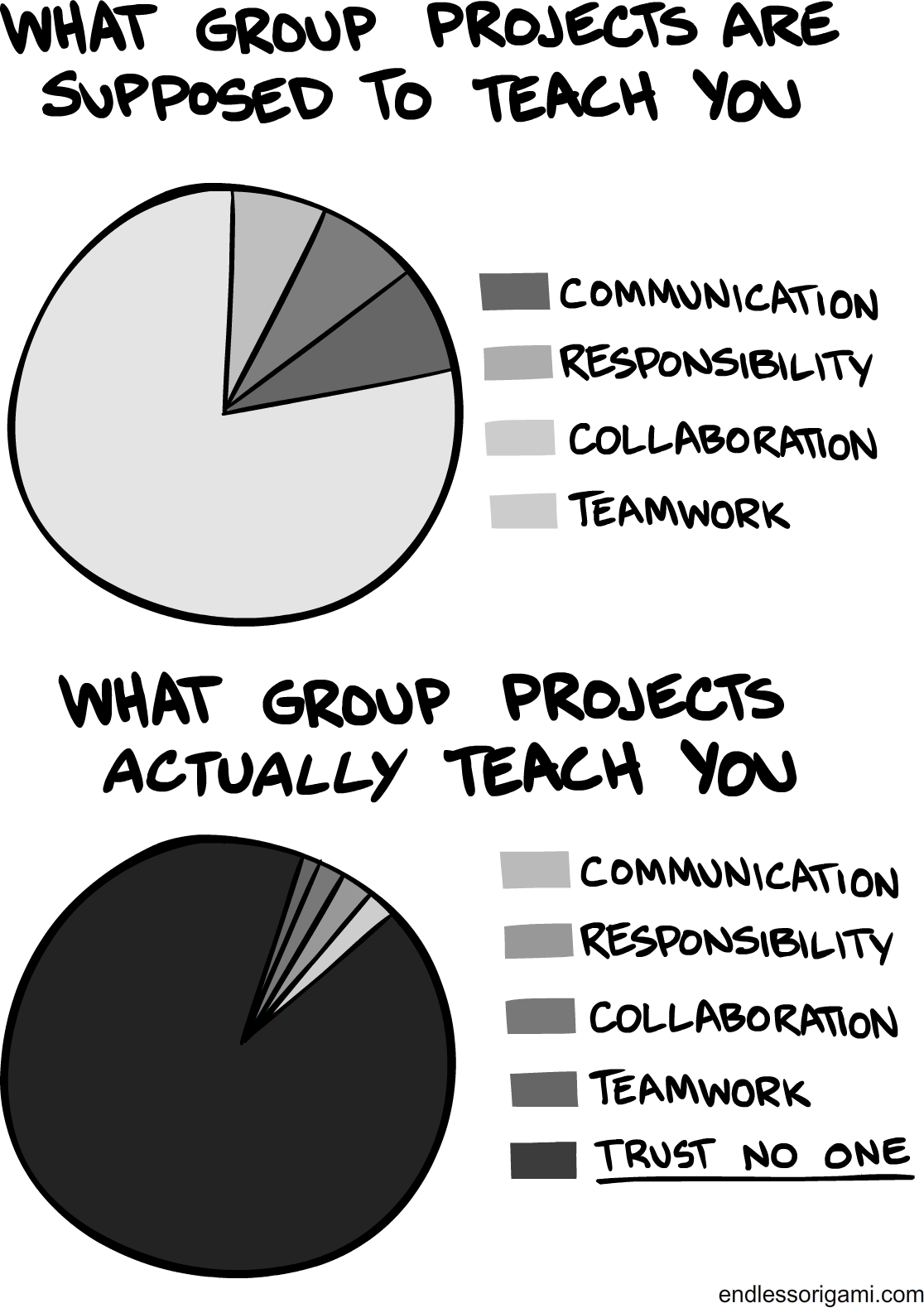

Most of the software engineers we know have spent anywhere from 4 to 10 years in school learning about computer science and software engineering. And yet there are hardly any curricula1 that actually teach you how to communicate and collaborate in a team or a company. Sure, most students are required to participate in a group project at some point in their academic career, but there’s a big difference between teaching someone how to successfully work with another person and throwing him into a situation of forced collaboration. Most students end up jaded by the experience.

The Pitch

Being a successful programmer isn’t just about learning the latest languages or writing the fastest code. Professional coders almost always work in teams, and it turns out that one’s team directly affects that individual’s productivity and happiness more than many people would like to admit.

The basic idea of this book is simple: writing software is a team sport, and we posit that the human factors involved have as much influence on the outcome as the technical factors. Even if they’ve spent decades learning the technical side of programming, most people haven’t really focused on the human component. Learning to collaborate is just as important to success. If you invest in the “soft skills” of engineering, you can have a much greater impact for the same amount of effort.

1 We’ve read PeopleWare by Tom DeMarco, and it’s a great book, but it’s not so much a book for individual contributors to learn how to work more efficiently with humans as it is a book for managers to learn how to make teams more successful.

Get Debugging Teams now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.