Chapter 1. Mommy, What’s a Social User Experience Pattern?

I have a dream for the Web...and it has two parts. In the first part, the Web becomes a much more powerful means for collaboration between people. I have always imagined the information space as something to which everyone has immediate and intuitive access, and not just to browse, but to create. Furthermore, the dream of people-to-people communication through shared knowledge must be possible for groups of all sizes, interacting electronically with as much ease as they do now in person.

A Little Social Backstory...

Social design for interactive digital spaces has been around since the earliest bulletin board systems. The most famous being The Well (1985), which was described by Wired magazine in 1997[1] as “the world’s most influential online community” and predated the World Wide Web and browser interfaces by several years.

Since the beginning of connected computers, we have tried to have computer-mediated experiences between people. As Clay Shirky notes in a 2004 Salon article, “Online social networks go all the way back to the Plato BBS 40 years ago!”

In the early days of the Web, social experiences were simply called community and generally consisted of message boards, groups, list-servs, and virtual worlds. Amy Jo Kim, author and community expert, calls these “place-centric” gathering places. Community features allowed users to talk and interact with one another, and the connection among people was usually based on the topic of interest that drew them to the site in the first place. Communities formed around interests, and relationships evolved over time. There was little distinction between the building of the tools to enable these gatherings and the groups of people who made up the community itself. Bonds were formed in this space but generally didn’t exist in the real (offline) world.

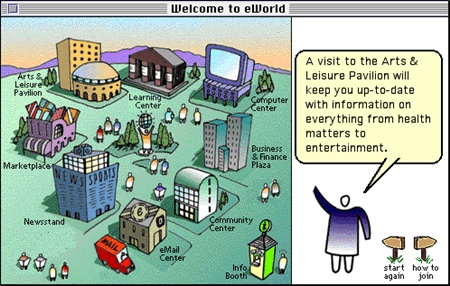

The interfaces and interaction design for these types of tools were all over the board—from graphical representations like eWorld (see Figure 1-1) to scary-looking, only for early adopters, text-only BBSs, to the simple forms of AOL chat rooms.

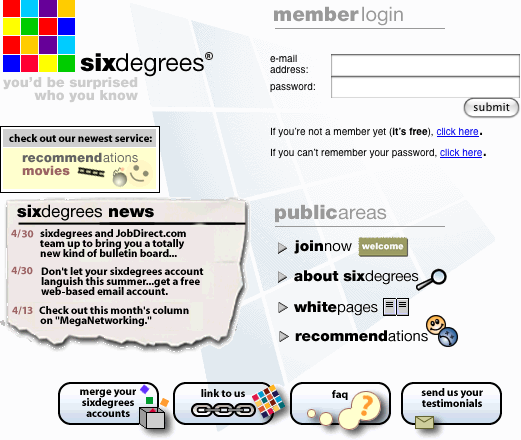

The first example that straddled the line between community and what we now call social networks was the site SixDegrees.com (1997; see Figure 1-2). SixDegrees showcased connections among people, allowed users to create and manage their personal profiles, and brought people together based on interests and other features. Sound familiar?

Somewhere along the way, though, before the dot-com bust, community became a dirty word—most likely because it was overly resource-intensive to build and care for, and no one had quite figured out how to make money from all that work.

With the advent of Web 2.0, and the second wave of websites and applications and the richer experiences they offer—more sophisticated technologies and faster bandwidth for the masses—social networking has taken on a new life. Suddenly, it is all the rage, and every site must have social features. In this phase, social has many more components and options available to users, but still generally means features or sites that allow interaction in real or asynchronous time among users. The tools are more robust, storage space is more ample, and more people are online to participate. The increase in online population is a major driving force for the shift to prioritizing these types of features and sites. There is critical mass now. By 2006, 73% of Americans, 64% of Europeans, and over 50% in the rest of the world were online and participating.

Another key difference between the first cycle of social and now is that the social network—the real relationships with people that we know and care about—is key to the interactions and features. Features are gated based on the degrees of connection between two people. Many of the tools and websites offer features and functions that support existing offline relationships and behaviors. These sites count on each person bringing his personal network into the online experience. The concept of tribes and friends has become more important than ever and has driven the development of many products.

What was ho-hum in 1997 is now the core—for user features as well as opportunities for making money. Additionally, the power of the many, or the wisdom of crowds, is being leveraged to exert some control over content creation and self-moderation processes. Companies are learning that successful social experiences shouldn’t and can’t be overly controlled. They are learning they can leverage the crowd to do some of the heavy lifting, which in turn spares them some of the costs. User-generated content has helped many businesses and the participating community keep things moderated.

The other factor contributing to the spread of these types of features is the expertise of a new generation of users. These folks have grown up with technology and expect it to help facilitate and mediate all their interactions with friends, colleagues, teachers, and coworkers. They move seamlessly from computer to their mobile device or phone and back, and they want the tools to move with them. They work with technology, they play in technology, they breathe this technology, and it is virtually invisible to them.

The terms community, social media, and social networking all describe these kinds of tools and experiences. The terms often are used interchangeably, but they provide different views and facets of the same phenomenon.

In a paper published in the Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication in 2007, danah boyd, a noted researcher specializing in social network sites, and Nicole B. Ellison defined social network sites as “web-based services that allow individuals to (1) construct a public or semi-public profile within a bounded system, (2) articulate a list of other users with whom they share a connection, and (3) view and traverse their list of connections and those made by others within the system. The nature and nomenclature of these connections may vary from site to site.”

According to Wikipedia, “social media is the use of electronic and Internet tools for the purpose of sharing and discussing information and experiences with other human beings,” and it defines social networking as “a service which focuses on building online communities of people who share interests and activities, or who are interested in exploring the interests and activities of others. Most social network services are web based and provide a variety of ways for users to interact, such as e-mail and instant messaging services.” Community is defined as the group of people who utilize these environments and tools.

Well, What About That Social Media? Can You Expand on That?

The term social media first came on our radar as a way of generalizing what was going on with blogs circa 2002. The combination of blogging with RSS (newsfeeds, feedreaders)—sometimes in the same application (as with Dave Winer’s Radio Userland software)—enabled a call-and-response, many-to-many conversational ecosystem to arise, become a bubble, calve into many smaller overlapping and distinct subcommunities, and so on.

In that scenario, the blog posts were the media, but then (as now) much blogging involved linking to sources that themselves might come from the traditional, mainstream media (or MSM, as some of the political bloggers tend to call it) or from other independent voices. Many people online realized they were consuming much of their media (news, gossip, video clips, information) through social intermediaries: reading articles when a more prominent blogger linked to them, discovering media fads and memes by following BoingBoing or many other similar trend-tracking sites, and tuning in to the blogs and publications of like-minded people and relying on them to filter the vast, unfathomable information flow for those valuable nuggets of relevancy.

Along the way, the term social media began to stand in for Web 2.0, or the Social Web, or social networking, or (now) the experiences epitomized by Facebook and Twitter. Christian called this “the living web” in his last book, The Power of Many: How the Living Web is Transforming Politics, Business, and Everyday Life (Wiley). Technorati tried branding it as the “world live web.” The idea is that as the Web becomes more social (that’s the word we’ve all converged on), there is an element of it that is read-write, that involves people writing and revising and responding to one another, not in a one-to-one or one-tomany fashion, but many-to-many. The problem with using social media as a generic term for the entire Internet-enabled social context is that the word “media,” already slippery (does it refer to works of creation, or to finding relevant news/media items, or to public chatter and commentary, or all of these things?), starts to add nothing to the phrase, and doesn’t really address the social graph.

Most recently, we’ve seen a proliferation of social media marketing experts and gurus online, and their messages range from the sublime (that marketing can truly be turned inside out as a form of customer service, through Cluetrainful engagement[2] with customers, i.e., treating them as human beings through ordinary conversations and public responsiveness), to the mundane (as in the early days of the Internet, every local market has its village explainers), to the ridiculous (a glorified version of spam).

The collection of patterns that comprise this book were once labeled “social media patterns,” after the social media toolkit that Matt Leacock started at Yahoo!, but as it evolved, it became clear that we were using “social media” to mean “social networking” or “involving the social graph” or just “social,” so for clarity’s sake, we’re using it to refer to “media that is created, filtered, engaged with, and remixed socially.”

Here’s a similar, but slightly more community-oriented definition of social media from Harjeet Gulati:

Social Media collectively refers to content (in the form of Text (Blogs, Discussion Forums, Wikis), Voice (Podcasts), or Video (YouTube) that is generated by the community of users for consumption within the same community. In this model, the role of Publisher and Consumer of information is delegated to the community at large. The role of the Channel becomes key in this model even as the degree of control that the community exercises over the content that is displayed within the boundaries of a given system varies. Where the term “media” meant traditional channels like Newspaper, Radio and Television, the advent of the Web in the early nineties accelerated the inclusion of the Web as a medium to reach out to others. The content ownership in traditional media continued to be with the “publishers” of content—the production houses, newspapers, tv channels, and radio stations. Content Owners/Publishers, the Channel and the Consumers were clearly differentiated. As the Web continued to evolve, the term “Social Media” has come to dominate the discussion. Social Media encourages a participative, collective model of content creation, distribution and usage and is more representative of the tastes and inclinations of the community at large.

We find it most useful to focus on the social objects (which may be media objects, but may also be such things as calendar events) and the activities people can do with them, and with one another, through our social interfaces.

For a further exploration of this term, see also “Social Media in Plain English” (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MpIOClX1jPE) from Common Craft.

What Do We Mean by Principle, Best Practice, and Patterns?

With the growing expectation of seamless experiences, it is important for designers to see the emerging standards and to understand how one experience of a site and its interactions affects expectations for the next site. By working with standard and emerging best practices, principles, and interaction patterns, the designer takes some of the burden of understanding how the application works off the user, who then can focus on the unique properties of the social experience she is building.

To start, we do define these three things differently. They live along a continuum, from prescriptive (rules you should follow) to assumptions (a basic generalization that is accepted as true) to process (ways to approach thinking about these concepts).

Principle: A Basic Truth, Law, or Assumption

Principles are basic assumptions that have been accepted as true. In interaction design, they can lend guidance for how to approach a design problem, and have been shown to be generally true with respect to a known user experience problem or a set of accepted truths. Principles don’t prescribe the solution, though, like an interaction pattern does; instead, they support the rationale behind an interaction design pattern or set of best practices.

Practice (or Best Practice): A Habitual or Customary Action or Way of Doing Something

Best practices are funny things. They are often confused with principles or interaction patterns. They fall along the continuum and are less prescriptive than an interaction pattern solution—at least in our definition. We often include best practices inside an interaction pattern. The best practice helps clarify how to approach a design solution, and is generally the most efficient and effective way to solve the problem, although not necessarily the only way.

Pattern: A Model or Original Used As an Archetype

When we developed the Yahoo! Pattern Library, we defined a pattern as:

Common, successful interaction design components and design solutions for a known problem in a context.

Patterns are used like building blocks or bricks. They are fundamental components of a user experience and describe interaction processes. They can be combined with other patterns as well as other pieces of interface and content to create an interactive user experience. They are technology and visually agnostic, meaning we do not prescribe particular technological solutions or visual design aesthetics in the patterns. User experience design patterns give guidance to a designer for how to solve a specific problem in a particular context, in a way that has been shown to work over and over again.

The notion of using interaction design patterns in the user experience design process follows the model that computer software programming took when it adopted the concepts and philosophies of Christopher Alexander. Alexander, an architect, wrote the book A Pattern Language. In his book he describes a language—a set of rules or patterns for design—for how to design and build cities, buildings, and other human spaces. The approach is repeatable and works at various levels of scale.

Alexander says that “each pattern describes a problem which occurs over and over again in our environment, and then describes the core of the solution to that problem, in such a way that you can use this solution a million times over, without ever doing it the same way twice.”

In addition to developing this language of elemental repeatable patterns, he was concerned with the human aspect of building. In a 2008 interview, Alexander says that his ideas “make [homes] work so that people would feel good.” This human approach and concern for the person (as user) is part of what has appealed to both software developers and user experience designers.

The idea of building with a pattern language was adopted by the computer software industry in 1987, when Ward Cunningham and Kent Beck began experimenting with the idea of applying patterns to programming. As Ward says, they “looked for a way to write programs that embraced the user, where users felt supported by the computer program, not interrogated by the computer program.”

This approach took off, and in 1995 the book Design Patterns: Elements of Reusable Object-Oriented Software by Erich Gamma, Richard Helm, Ralph Johnson, and John Vlissides (known as the Gang of Four) was published.

In 1997, Jenifer Tidwell published a collection of user interface patterns for the human-computer interaction (HCI) community based on the premise that capturing the collective wisdom of experienced designers helps educate novice designers and gives the community as a whole a common vocabulary for discussion. She specifically stated that she was attempting to create an Alexandrian-like language for interface designers and the HCI community. The evolution of that site and her work became the book Designing Interfaces, published in 2005 by O’Reilly Media.

Several others published collections on the Web, including Martijn van Welie, a long-time proponent of patterns in the interaction design realm, which in turn inspired my (Erin’s) team at Yahoo! to publish portions of our internal interaction pattern library to the public in 2006.

I had joined Yahoo! in 2004 to build a pattern library for the ever-growing user experience design team and to create a common vocabulary for the network of sites that Yahoo! produced for its hundreds of millions of global users. We built the library in a collaborative manner, utilizing the most successful, well-researched design solutions as models for each pattern. Designers from across the company contributed patterns, commented and discussed their merits, added new information as technology and users changed, and moderated the quality and lifecycle of each pattern. In 2006, spearheaded by Bill Scott, we were able to go public with our work with a subset of the internal library. The work has been very well received by the interaction design and information architecture community, and has inspired many in their design work. Since 2007, Christian has been further evangelizing the library and bridging the gaps between design and development and open source communities.

The notion of having a suite of reusable building blocks to inform and help designers develop their sites and applications has gained traction within the interaction design community as the demands for web and mobile interfaces have become more complex. When the Web was mostly text, there wasn’t a whole lot of variety to how a user interacted with a site, and the toolkit was small. The complexity of client applications was difficult at best to duplicate online. But that was then. Now, whole businesses and industries rely on easy-to-use web-based software to conduct their business. There is more need than ever to have a common language for designers and developers. And as social becomes integrated into every facet of interactive experiences, it is important to put a stake in the ground about just what those pieces should be and how they should and shouldn’t behave.

The Importance of Anti-Patterns

The term anti-patterns was coined in 1995 by Andrew Koenig in the C++ Report, and was inspired by the Gang of Four’s book Design Patterns.

Koenig defined the term with two variants:

Those that describe a bad solution to a problem that resulted in a bad situation.

Those that describe how to get out of a bad situation and how to proceed from there to a good solution.

Anti-patterns became a popular method for understanding bad design solutions in programming with the publication of the book Anti-Patterns: Refactoring Software, Architectures, and Projects in Crisis by William Brown et al.

For our purposes, anti-patterns are common mistakes or a bad solution to a common problem. It is sometimes easier to understand how to design successfully by dissecting what not to do. In the world of social experiences, often the anti-patterns have some sort of jarring or malicious side effects.

The anti-patterns we illustrate will point out why the solution seems good and why it turns out to be bad, and then we will discuss refactored alternatives that are more successful or gentler to the user experience.

So, That’s All the Little Parts: Now What?

Our approach for the rest of this book is similar to Christopher Alexander’s, in that we start with a foundational set of high-level practices that underpin the individual interactions detailed in subsequent chapters.

In each section, we talk about which patterns build on others and how you can combine patterns to create a robust experience. We cross-reference patterns and give examples from the wild where we see examples of these patterns in action.

The social patterns support the entire lifecycle that a user may experience within a site or application, from signing up to actively participating, to building a reputation, to dating or collaborating with friends, to collaborative games and even moderation. We are building a vocabulary and language for social application design in the same spirit as Alexander:

We were always looking for the capacity of a pattern language to generate coherence, and that was the most vital test used, again and again, during the process of creating a language. The language was always seen as a whole. We were looking for the extent to which, as a whole, a pattern language would produce a coherent entity.

Further Reading

Anti-Patterns: Refactoring Software, Architectures, and Projects in Crisis, by William Brown, Raphael Malveau, Skip McCormick, and Tom Mowbray, Wiley, 1998

Community Building on the Web: Secret Strategies for Successful Online Communities, by Amy Jo Kim, Peachpit Press, 2000

Design Patterns, by Erich Gamma, Richard Helm, Ralph Johnson, and John M. Vlissides, Addison-Wesley Professional, 1994

Design for Community, by Derek Powazek, Waite Group Press, 2001

Designing for the Social Web, by Joshua Porter, New Riders Press, 2008

Designing Interfaces, by Jenifer Tidwell, O’Reilly Media, Inc., 2005

Groundswell, by Charlene Li and Josh Bernoff, Harvard Business School Press, 2008

A Pattern Language: Towns, Buildings, Construction (Center for Environmental Structure Series), by Christopher Alexander, Oxford University Press, 1977

Social Media in Plain English, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MpIOClX1jPE

A Timeless Way of Building, by Christopher Alexander, Oxford University Press, 1979

The Virtual Community: Homesteading on the Electronic Frontier, by Howard Rheingold, The MIT Press, 2000

The Well: A Story of Love, Death and Real Life in the Seminal Online Community, by Katie Hafner, Carroll, Graf Publishers, 2001

[1] Hafner, Katie. 1997. “The Epic Saga of The Well: The World’s Most Influential Online Community (And It’s Not AOL).” Wired, 5.05, http://www.wired.com/wired/archive/5.05/ff_well_pr.html.

[2] The Cluetrain Manifesto (http://www.cluetrain.com/)

Get Designing Social Interfaces now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.