Your primary name server is already up and running; you’ve been talking to it via the DNS console. You’ve created a zone and populated it with information. Then you directed the server to write out zone data files with the Action → Update Server Data Files command. To be sure that everything is okay, you should stop and restart the server and then check the Event Log for any messages or errors.

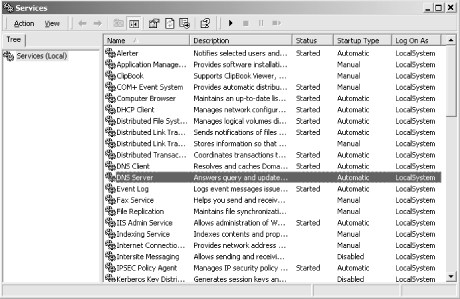

There are several ways to start and stop the DNS server. First, you can control it just like any other Windows 2000 service: with the Services MMC snap-in. Select Start → Programs → Administrative Tools → Services. You’ll see a window like Figure 4-21.

Your system should look like this: the server should be running (that is, it should be started). Select the server as we’ve done by clicking anywhere on the DNS Server line. Select Action → Stop. After the server stops, select Action → Start. In a few seconds, the server should be running again.

While you’ve got this window open, check to make sure that the DNS server is being started automatically on bootup. You want to see Automatic in the Startup Type column (and not Manual or Disabled). To change the startup behavior, double-click on the service and choose the appropriate behavior in the Startup Type field of the resulting window.

You can also start and stop the DNS server from within the DNS console. With the server selected in the left pane, select Action → All Tasks. You’ll see a menu with choices that include Start, Stop, and Restart. (The latter does just what you’d expect: stops, then starts, the server.)

Finally, you can start and stop the DNS server from the good old DOS command line: net start dns will start the server, and net stop dns stops it. Of course, this command must be run on the system on which the DNS server is running, which is not necessarily the same system on which the DNS console is running.

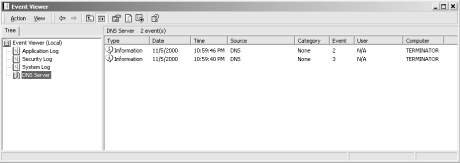

Now you need to check the Event Log. Start the Event Viewer by selecting Start → Programs → Administrative Tools → Event Viewer. Under Windows 2000, the DNS server has its own category in the Event Log. Select DNS Server in the left pane and you should see a window like the one in Figure 4-22.

DNS Server Event ID 3 is “The DNS server has shutdown.” and Event ID 2 is “The DNS server has started.” (More events are listed in Chapter 7.) These two events are just what you want to see: a normal server shutdown and startup. We’re reading from bottom to top since Event Viewer’s default view shows newest events first. We also cleared the Event Log before we stopped and started the server—that’s why only these two events are showing.

If there were any other messages or errors, we’d take steps to correct them now. To be honest, we didn’t expect any problems because we entered all the data via the DNS console. Since it performs some syntax and sanity checking, it’s hard to enter bad data to make the name server upset enough to complain in the Event Log. Still, it doesn’t hurt to check. If you ever start editing zone data files by hand (which we don’t recommend), you definitely need to check the Event Log.

If you have correctly set up your local domain and your connection to the Internet is up, you should be able to look up a local and a remote domain name. We’ll step you through the lookups with nslookup. This book contains an entire chapter on this topic (Chapter 12), but we will cover nslookup in enough detail here to do basic name-server testing.

You can use nslookup to look up any type of resource record, and it can be directed to query any name server. By default, it looks up A (address) records using the name server on the local system. To look up a host’s address with nslookup, run nslookup with the host’s name as the only argument. A lookup of a local name should return almost instantly.

We ran nslookup to look up carrie:

C:\> nslookup carrie

Server: terminator.movie.edu

Address: 192.249.249.3

Name: carrie.movie.edu

Address: 192.253.253.4If looking up a local name works, your local name server has been configured properly for your domain. If the lookup fails, you’ll see something like this:

*** terminator.movie.edu can't find carrie: Non-existent domain

This means that either carrie is not in your data—check the DNS console or the zone data file—or some name server error occurred (but you should have caught the error when you checked the Event Log).

When nslookup is given an address to look up, it knows to make a PTR query instead of an address query. We ran nslookup to look up carrie’s address:

C:\> nslookup 192.253.253.4

Server: terminator.movie.edu

Address: 192.249.249.3

Name: carrie.movie.edu

Address: 192.253.253.4If looking up an address works, your local name server has been configured properly for your in-addr.arpa domain. If the lookup fails, you’ll see the same error message as when you looked up a name.

The next step is to use the local name server to look up a remote name, such as ftp.uu.net or another system you know on the Internet. Don’t forget to add a period at the end of your input so the system doesn’t automatically append the origin, movie.edu.

This command may not return as quickly as the last one. If nslookup fails to get a response from your name server, it will wait a little over a minute before giving up:

C:\> nslookup ftp.uu.net.

Server: terminator.movie.edu

Address: 192.249.249.3

Name: ftp.uu.net

Address: 192.48.96.9If this lookup works, your name server knows where the root name servers are and how to contact them to find information about domains other than your own. If it fails, there is a problem with the cache file or the network. The cache file might be empty or missing address records for the root name servers. Or perhaps the network is broken somewhere and you can’t reach the name servers for the remote domain. Try a different remote domain name.

If these first three lookups succeeded, congratulations! You have a primary master name server up and running. At this point, you are ready to start configuring your slave name server.

While you are testing, though, run one more test. Try having a remote name server look up a name in your zone. This will work only if your parent name servers have already delegated your zone to the name server you just set up. If your parent required you to have your two name servers running before delegating your zone, skip ahead to the next section.

To make nslookup use a remote name server to look up a local name, give the local host’s name as the first argument and the remote server’s name as the second argument. Again, if this doesn’t work, it may take a little longer than a minute before nslookup gives you an error message. For instance, to have gatekeeper.dec.com look up carrie, we’d enter:

C:\> nslookup carrie gatekeeper.dec.com.

Server: gatekeeper.dec.com.

Address: 204.123.2.2

Name: carrie.movie.edu

Address: 192.253.253.4If the first two lookups worked but using a remote name server to look up a local name failed, you may not be registered with your parent name server. That is not a problem at first because systems within your zone can look up the names of other systems within and outside your zone. You’ll be able to send email and ftp to local and remote systems. Some systems won’t allow FTP connections if they can’t map your address back to a name. But not being registered will shortly become a problem. Hosts outside of your zone cannot look up names within your zone. You will be able to send email to friends in remote domains, but you won’t get their responses. To fix this problem, contact someone responsible for your parent zone and have them check the delegation of your zone.

Get DNS on Windows 2000, Second Edition now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.