Warning

At the time of this writing, the Editor and its plug-in architecture were

undergoing some significant enhancements. Thus, you may find that

this section is slightly more general with respect to technical

details than many other sections of the book.

An increasing number applications are utilizing rich text

editing capability; in fact, it's probably fair to say that if you

have a slick RIA interface and then hand it to the user with an

ordinary textarea element (even a

Textarea dijit), it'll probably

stick out like a sore thumb. Fortunately, the Editor dijit contains all of the common rich

text editing functionality, with absolutely minimal overhead on your

part.

Tip

You may find this reference interesting as you read the rest of this section: http://developer.mozilla.org/en/docs/Rich-Text_Editing_in_Mozilla.

Dojo builds upon native browser controls that enable content to

be editable. As a little history lesson, Internet Explorer 4.0

introduced the concept of design mode, in which

it became possible to edit text in a manner consistent with simple

rich text editors, and Mozilla 1.3 followed suit to implement what's

essentially the same API that eventually became formalized as the

Midas Specification (http://www.mozilla.org/editor/midas-spec.html). Other

browsers have generally followed in the same direction—with their own

minor nuances. In any event, most of the heavy lifting occurs by first

explicitly making a document editable and then using the JavaScript

execCommand function to do the

actual markup. Following the Midas Specification, something along the

lines of the following would do the trick:

// Make a node editable...perhaps a div with a set height and width

document.getElementById("foo").contentDocument.designMode="on";

/* Select some text... */

// Set the selection to italic. No additional arguments are needed.

editableDocument.execCommand("Italic", false, null);As you might imagine, you can use an arsenal of commands for

manipulating content via execCommand, standardize the differences

amongst browser implementation, assemble a handy toolbar, provide some

nice styling, and wrap it up as a portable widget. In fact, that's

exactly what Dijit's Editor does

for you. Although Editor provides a

slew of features that seem overwhelming at a first glance, the basic

usage is quite simple. Example 15-12

illustrates an out of the box Editor from markup along with some light

styling and a couple of buttons that interact with it.

Tip

Without any styling at all, the Editor has no border, spans the width of

its container, and comes at a default height of 300px. The light

styling here simply provides a background and adjusts the Editor 's height to slightly smaller than

its container so that the content won't run out of the visible

background and into the buttons.

Example 15-12. Typical Editor usage

<div style="margin:5px;background:#eee; height: 400px; width:525px">

<div id="editor" height="375px" dojoType="dijit.Editor">

When shall we three meet again?<br>

In thunder, lightning, or in rain?

</div>

</div>

<button dojoType="dijit.form.Button">Save

<script type="dojo/method" event="onClick" args="evt">

/* Save the value any old way you'd like */

console.log(dijit.byId("editor").getValue( ));

</script>

</button>

<button dojoType="dijit.form.Button">Clear

<script type="dojo/method" event="onClick" args="evt">

dijit.byId("editor").replaceValue("");

</script>

</button>It's well worth a moment of your time to interact with the

Editor and see for yourself that

getting all of that functionality with such minimal effort really

isn't too good to be true. Note that the Editor renders plain HTML, so saving and

restoring content should not involve any unnecessary translation.

Then, when you're ready to take a look at some of the many things that

the Editor can do for you, skim

over the feature list in Table 15-14.

Tip

The Editor API is by far

the most complex in Dijit, and at the time of this writing,

refactoring efforts to tame it were being seriously entertained.

Thus, the following table contains a small subset of the most useful

parts of the API. See the source file documentation for the complete

listing if you really want to hack on the

Editor.

Table 15-14. Small subset of the Editor API

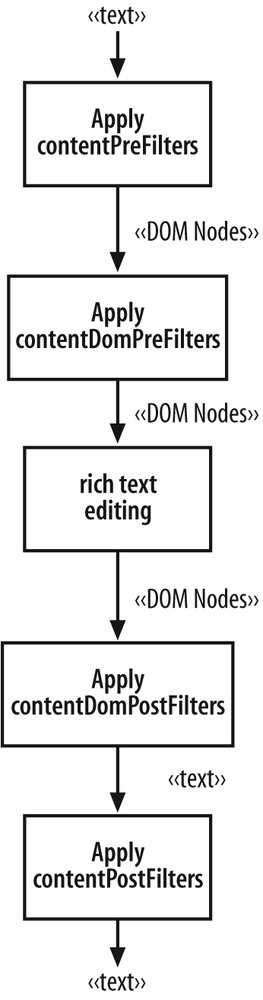

The Editor 's lifecycle

supports three basic phases, shown in Figure 15-6. The following list

summarizes these phases and the work involved in each:

- Deserializing content

The loading phase entails loading a text stream supplied by a DOM node, converting it into a DOM tree, and placing it into the display for user interaction. Sequences of JavaScript functions may be applied to both the text stream as well as the DOM tree in order, as needed, in order to filter and convert content. Common examples of filters might entail such tasks as converting linebreaks from a plain text document into

<br>tags so that the content displays as proper HTML in the editor.- Interacting with content

The interaction phase is just like any other rich text editing experience. Common operations such as markup may occur, and an undo stack is stored based on either a time interval or on the basis of every time the display changes.

- Serializing content

When editing ends by way of the

Editor'sclosemethod, the contents are serialized from a DOM tree back into a text stream, which then gets written back into the node of origin. From there, an event handler might send it back to a server to persist it. Like the deserializing phase, sequences of JavaScript functions may optionally be applied to manipulate the content.

Although the Editor

provides an onslaught of highly useful features of its own, sooner

or later you'll be wishing that it were possible to tightly

integrate some piece of custom functionality. Its plug-in

architecture is your ticket to making that happen. A plug-in is just

a way of encapsulating some additional functionality that, while

useful, maybe shouldn't be a stock component; it could be anything

from handling some special key combinations to providing a custom

menu item with some canned commands that automate part of a

workflow.

Snapping a plug-in into Editor is quite simple, and you may not

have realized it, but everything in the toolbar you thought was

built right in is technically a plug-in with one of the following

self-descriptive values.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

You can configure plug-ins by providing either the plugins or extraPlugins attribute and give it a list

of valid plug-ins that you have first dojo.require d into the page. By default,

plugins contains all of the items

in the toolbar that you see by default, and if you override it and

provide something like plugins="['bold','italic']", then all

you'd see in the toolbar is the list of plugins you provided. However, the

extraPlugins attribute adds extra

plugins on top of what is already

configured in plugins if you want

to throw in a few extras.

Several packages of prefabricated plug-ins are available with

the toolkit and are commonly used as values to extraPlugins ; they are located in the

dijit/_editor/plugins directory and include the

following:

AlwaysShowToolbarShifts the contents of the toolbar, as needed, so that multiple rows of controls are displayed, and it always remains visible. (If you resize the window to be less than the width of the toolbar, the default action is to display a horizontal scrollbar and only display the portion of the toolbar that would normally be visible.) You must pass in

dijit._editor.plugins.AlwaysShowToolbartopluginsorextraPluginsto enable this plug-in.EnterKeyHandlingProvides a means of uniformly handling what happens when the Enter key is pressed amongst all browsers. For example, you can specify whether to insert a series of paragraph tags to surround the new text, a break tag, a set of

DIVStags, or not to disable the handling of the Enter key entirely. You must pass indijit._editor.plugins.EnterKeyHandlingtopluginsorextraPluginsto enable this plug-in.

Warning

The Editor 's plug-in

architecture needs some work, and discussions are ongoing about

how to improve it. Progress is already being made, and you can

track it for yourself at http://trac.dojotoolkit.org/ticket/5707. In other

words, if you want to create custom plug-ins, you'll likely have

to hack on the Editor.js source code a bit

until the plug-in architecture is smoothed out a bit more.

Also, don't forget that you have to manually dojo.require in the plug-in that you are

using. The plug-in architecture does not perform any sort of

autodetection at this time.

Currently, the default means of handling the Enter key is

determined by the EnterKeyHandling attribute blockNodeForEnter, which has a default

value of 'P'. Currently, there

isn't really a better way of changing it than by extending this

plug-in's prototype and overriding it like so:

dojo.addOnLoad(function( ) {

dojo.extend(dijit._editor.plugins.EnterKeyHandling, {

blockNodeForEnter : "div" // or "br" or "empty"

});

});FontChoiceProvides a button with a dialog for picking a font name, font size, and format block. Arguments to

pluginsorextraPluginsmay befontName,fontSize, orformatBlock.LinkDialogProvides a button with a dialog for entering a hyperlink source and displayed value. Arguments to

pluginsorextraPluginsmay becreateLink.TextColorProvides options for specifying the foreground color or background color for a range of text. Arguments to

pluginsorextraPluginsmay beforeColororhiliteColor.ToggleDirProvides a means of involving the HTML

dirattribute on theEditor(regardless of how the rest of the page is laid out) so that theEditor's contents could be left-to-right or right-to-left. Arguments topluginsorextraPluginsmay betoggleDir.

To make matters a little less muddy, consider the differences in the snippets of markup shown in Table 15-15 when creating an editor.

Table 15-15. Different approaches to creating an editor

Code | Effect |

|---|---|

| Creates an |

| Creates an |

| Creates an |

| Creates an |

Get Dojo: The Definitive Guide now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.