Chapter 1. Node Overview

1.1 The Document Object Model (a.k.a. the DOM) Is a Hierarchy/Tree of JavaScript Node Objects

When you write an HTML document, you encapsulate HTML content inside other HTML content. By doing this, you set up a hierarchy that can be expressed as a tree. Often this hierarchy or encapsulation system is indicated visually by indenting markup in an HTML document. The browser, when loading the HTML document, interrupts and parses this hierarchy to create a tree of node objects that simulates how the markup is encapsulated.

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html lang="en">

<head>

<title>HTML</title>

</head>

<body>

<!-- Add your content here-->

</body>

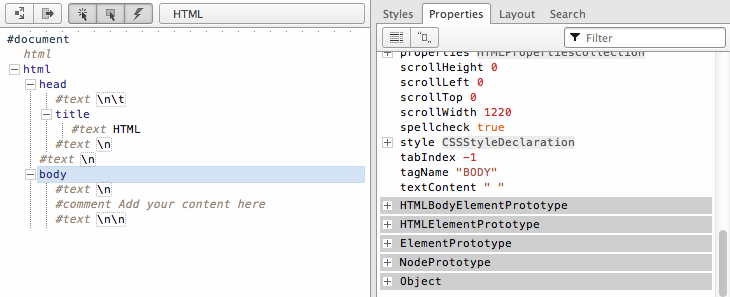

</html>The preceding HTML code, when parsed by a browser, creates a document that contains nodes structured in a tree format (i.e., DOM). In Figure 1-1, I reveal the tree structure from the preceding HTML document using Opera’s Dragonfly DOM Inspector.

On the left, you see the HTML document in its tree form. And on the

right, you see the corresponding JavaScript object that represents the

selected element on the left. For example, the selected

<body> element, highlighted in blue, is an

element node and an instance of the HTMLBodyElement

interface.

What you should take away here is that HTML documents get parsed by a browser and converted into a tree structure of node objects representing a live document. The purpose of the DOM is to provide a programmatic interface for scripting (removing, adding, replacing, eventing, and modifying) this live document using JavaScript.

1.2 Node Object Types

Here is a list of the most common types of nodes (i.e.,

nodeType/node classifications) one encounters when

working with HTML documents:

DOCUMENT_NODE(e.g.,window.document)ELEMENT_NODE(e.g.,<body>,<a>,<p>,<script>,<style>,<html>,<h1>)ATTRIBUTE_NODE(e.g.,class="funEdges")TEXT_NODE(e.g., text characters in an HTML document including carriage returns and whitespace)DOCUMENT_FRAGMENT_NODE(e.g.,document.createDocumentFragment())DOCUMENT_TYPE_NODE(e.g.,<!DOCTYPE html>)

I’ve listed the node types formatted (all uppercase, with _

separating words) exactly as the constant property is written in the

JavaScript browser environment as a property of the

Node object. These Node properties

are constant values and are used to store numeric code values that map to

a specific type of node object. For example, in the following code,

Node.ELEMENT_NODE is equal to 1. And

1 is the code value used to identify element

nodes.

<!DOCTYPE html> <html lang="en"> <body> <script> console.log(Node.ELEMENT_NODE) /* logs 1, one is the numeric code value for element nodes */ </script> </body> </html>

In the following code I log all the node types and their values.

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html lang="en">

<body>

<script>

for(var key in Node){

console.log(key,' = '+Node[key]);

};

/* the above code logs to the console the following

ELEMENT_NODE = 1

ATTRIBUTE_NODE = 2

TEXT_NODE = 3

CDATA_SECTION_NODE = 4

ENTITY_REFERENCE_NODE = 5

ENTITY_NODE = 6

PROCESSING_INSTRUCTION_NODE = 7

COMMENT_NODE = 8

DOCUMENT_NODE = 9

DOCUMENT_TYPE_NODE = 10

DOCUMENT_FRAGMENT_NODE = 11

NOTATION_NODE = 12

DOCUMENT_POSITION_DISCONNECTED = 1

DOCUMENT_POSITION_PRECEDING = 2

DOCUMENT_POSITION_FOLLOWING = 4

DOCUMENT_POSITION_CONTAINS = 8

DOCUMENT_POSITION_CONTAINED_BY = 16

DOCUMENT_POSITION_IMPLEMENTATION_SPECIFIC = 32 */

</script>

</body>

</html>The preceding code example gives an exhaustive list of all node types. For the purposes of this book, I’ll be discussing the shorter list of node types shown at the start of this section. These nodes will most likely be the ones you encounter when scripting an HTML page.

In Table 1-1, I list the name given to the

interface/constructor that instantiates the most common node types and

their corresponding nodeType classifications by number

and name. What I hope you take away from the table is that the

nodeType value (i.e., 1) is just a

numeric classification used to describe a certain type of node constructed

from a certain JavaScript interface/constructor. For example, the

HTMLBodyElement interface represents a node object that

has a node type of 1, which is a classification for

ELEMENT_NODEs.

Interface/constructor | nodeType (returned from .nodeType) |

| 1 (i.e.,

|

3 (i.e.,

| |

2 (i.e.,

ATTRIBUTE_NODE) | |

9 (i.e.,

DOCUMENT_NODE) | |

11 (i.e.,

| |

10 (i.e.,

| |

Notes

The DOM specification semantically labels nodes like

Node, Element,

Text, Attr, and

HTMLAnchorElement as interfaces, which they are, but

keep in mind that these are also the names given to the JavaScript

constructor functions that construct the nodes. As you read this book, I

will be referring to these interfaces (i.e., Element,

Text, Attr,

HTMLAnchorElement) as objects or constructor

functions, while the specification refers to them as interfaces.

ATTRIBUTE_NODE is not actually part of a tree,

but rather is listed for historical reasons. In this book, I do not

provide a chapter on attribute nodes and instead discuss them in Chapter 3, given that attribute nodes are sublike nodes

of element nodes with no participation in the actual DOM tree structure.

Be aware that the ATTRIBUTE_NODE is being deprecated

in DOM4.

I’ve not included detail in this book on

COMMENT_NODE, but you should be aware that comments

in an HTML document are Comment nodes and are similar

in nature to Text nodes.

As I discuss nodes throughout the book, I rarely refer to a

specific node using its nodeType name (e.g.,

ELEMENT_NODE). This is done to be consistent with

verbiage used in the specifications provided by the W3C and

WHATWG.

1.3 Subnode Objects Inherit From the Node Object

Each node object in a typical DOM tree inherits properties and

methods from Node. Depending on the type of node in the

document, there are also additional subnode objects/interfaces that extend

the Node object. The following list details the

inheritance model implemented by browsers for the most common node

interfaces (< indicates “inherited from”):

Object<Node<Element<HTMLElement< (e.g.,HTML*Element)Object<Node<Attr(this is deprecated in DOM4)Object<Node<CharacterData<TextObject<Node<Document<HTMLDocumentObject<Node<DocumentFragment

It’s important to remember not only that all node types inherit from

Node, but also that the chain of inheritance can be

long. For example, all HTMLAnchorElement nodes inherit

properties and methods from HTMLElement,

Element, Node, and

Object objects.

Note

Node is just a JavaScript constructor function.

Logically, therefore, Node inherits from

Object.prototype just like all objects in

JavaScript.

To verify that all node types inherit properties and methods from

the Node object, let’s loop over an

Element node object and examine its properties and

methods (including those that are inherited).

<!DOCTYPE html> <html lang="en"> <body> <a href="#">Hi</a> <!-- this is a HTMLAnchorElement which inherits from... --> <script> //get reference to element node object var nodeAnchor = document.querySelector('a'); //create props array to store property keys for element node object var props = []; //loop over element node object getting all properties and methods (inherited too) for(var key in nodeAnchor){ props.push(key); } //log alphabetical list of properties and methods console.log(props.sort()); </script> </body> </html>

If you run the preceding code in a web browser, you will see a long

list of properties that are available to the element node object. The

properties and methods inherited from the Node object

are in this list, as are a great deal of other inherited properties and

methods from the Element,

HTMLElement, HTMLAnchorElement,

Node, and Object objects. It’s not

my point to examine all these properties and methods now, but rather to

simply mention that all nodes inherit a set of baseline properties and

methods from their constructor as well as properties from the prototype

chain.

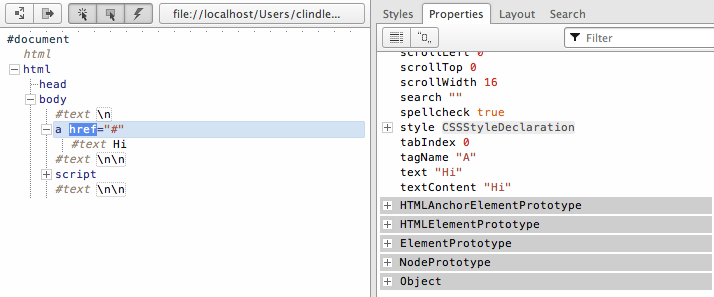

If you are more of a visual learner, consider the inheritance chain denoted from examining the previous HTML document with Opera’s DOM Inspector (see Figure 1-2).

Notice in Figure 1-2 that the anchor node inherits

from HTMLAnchorElement, HTMLElement, Element,

Node, and Object, all of which are

shown in the list of properties highlighted with a gray background. This

inheritance chain provides a great deal of shared methods and properties

to all node types.

Note

Adding your own custom methods and properties to the DOM is possible, given the mutable and dynamic nature of JavaScript. But generally, extending host objects comes with several problems, so it’s probably not a good idea to do so.

1.4 Properties and Methods for Working with Nodes

As we have been discussing, all node objects (e.g.,

Element, Attr,

Text, and so on) inherit properties and methods from a

primary Node object. These properties and methods are

the baseline values and functions for manipulating, inspecting, and

traversing the DOM. In addition to the properties and methods provided by

the node interface, a great deal of other relevant properties and methods

are provided by subnode interfaces such as the

document, HTMLElement, and

HTML*Element interfaces.

The following are the most common Node properties

and methods inherited by all node objects, including the relevant

inherited properties for working with nodes from subnode

interfaces.

- Node properties

childNodesfirstChildlastChildnextSiblingnodeNamenodeTypenodeValueparentNodepreviousSibling

- Node methods

appendChild()cloneNode()compareDocumentPosition()contains()hasChildNodes()insertBefore()isEqualNode()removeChild()replaceChild()

- Document methods

document.createElement()document.createTextNode()

HTML*ElementpropertiesinnerHTMLouterHTMLtextContentinnerTextouterTextfirstElementChildlastElementChildnextElementChildpreviousElementChildchildren

- HTML element method

insertAdjacentHTML()

1.5 Identifying the Type and Name of a Node

Every node has a nodeType and

nodeName property that is inherited from

Node. For example, Text nodes have a

nodeType code of 3 and a nodeName

value of #text. As I mentioned previously, the numeric

value 3 is a numeric code representing the type of underlying object the

node represents (i.e., Node.TEXT_NODE === 3).

Here are the values returned for nodeType and

nodeName for the node objects discussed in this book.

It makes sense to simply memorize these numeric codes for the more common

nodes, given that we are only dealing with five numeric codes.

<!DOCTYPE html> <html lang="en"> <body> <a href="#">Hi</a> <script> /* This is DOCUMENT_TYPE_NODE or nodeType 10 because Node.DOCUMENT_TYPE_NODE === 10 */ console.log( document.doctype.nodeName, /* logs 'html' also try document.doctype to get <!DOCTYPE html> */ document.doctype.nodeType //logs 10 which maps to DOCUMENT_TYPE_NODE ); //This is DOCUMENT_NODE or nodeType 9 because Node.DOCUMENT_NODE === 9 console.log( document.nodeName, //logs '#document' document.nodeType //logs 9 which maps to DOCUMENT_NODE ); /* This is DOCUMENT_FRAGMENT_NODE or nodeType 11 because Node.DOCUMENT_FRAGMENT_NODE === 11 */ console.log( document.createDocumentFragment().nodeName, //logs '#document-fragment' document.createDocumentFragment().nodeType /* logs 11 which maps to DOCUMENT_FRAGMENT_NODE */ ); //This is ELEMENT_NODE or nodeType 1 because Node. ELEMENT_NODE === 1 console.log( document.querySelector('a').nodeName, //logs 'A' document.querySelector('a').nodeType //logs 1 which maps to ELEMENT_NODE ); //This is TEXT_NODE or nodeType 3 because Node.TEXT_NODE === 3 console.log( document.querySelector('a').firstChild.nodeName, //logs '#text' document.querySelector('a').firstChild.nodeType /* logs 3 which maps to TEXT_NODE */ ); </script> </body> </html>

In case it’s not obvious, the fastest way to determine whether a

node is of a certain type is to simply check its

nodeType property. In the following code, I check to

see if the anchor element has a node number of 1. If it does, I can

conclude that it’s an Element node, because

Node.ELEMENT_NODE === 1.

<!DOCTYPE html> <html lang="en"> <body> <a href="#">Hi</a> <script> //is <a> a ELEMENT_NODE? console.log(document.querySelector('a').nodeType === 1); /* logs true, <a> is an Element node */ //or use Node.ELEMENT_NODE which is a property containing the numeric value of 1 console.log(document.querySelector('a').nodeType === Node.ELEMENT_NODE); //logs true, <a> is an Element node </script> </body> </html>

Determining the type of node you might be scripting can be very handy if you want to know which properties and methods are available to script the node.

Note

The values returned by the nodeName property

vary according to the node type. See the DOM4 specification for

details.

1.6 Getting a Node’s Value

The nodeValue property returns

null for most of the node types (except

Text and Comment). Its use is

centered on extracting actual text strings from Text

and Comment nodes. In the following code, I demonstrate

its use on all the nodes discussed in this book.

<!DOCTYPE html> <html lang="en"> <body> <a href="#">Hi</a> <script> /* logs null for DOCUMENT_TYPE_NODE, DOCUMENT_NODE, DOCUMENT_FRAGMENT_NODE, ELEMENT_NODE below */ console.log(document.doctype.nodeValue); console.log(document.nodeValue); console.log(document.createDocumentFragment().nodeValue); console.log(document.querySelector('a').nodeValue); //logs string of text console.log(document.querySelector('a').firstChild.nodeValue); //logs 'Hi' </script> </body> </html>

1.7 Using JavaScript Methods to Create Element and Text Nodes

When a browser parses an HTML document, it constructs the nodes and

tree based on the contents of the HTML file. The browser deals with the

creation of nodes for the initial loading of the HTML document. However,

it’s possible to create your own nodes using JavaScript. The following two

methods allow us to programmatically create Element and Text nodes

using JavaScript:

createElement()createTextNode()

Other methods are available but are not commonly used (e.g.,

createAttribute() and

createComment()). In the following code, I show how

simple it is to create element and text nodes.

<!DOCTYPE html> <html lang="en"> <body> <script> var elementNode = document.createElement('div'); console.log(elementNode, elementNode.nodeType); /* log <div> 1, and 1 indicates an element node */ var textNode = document.createTextNode('Hi'); console.log(textNode, textNode.nodeType); /* logs Text {} 3, and 3 indicates a text node */ </script> </body> </html>

Notes

The createElement() method accepts one

parameter that is a string specifying the element to be created. The

string is the same string that is returned from the

tagName property of an Element

object.

The createAttribute() method is deprecated and

should not be used for creating attribute nodes. Instead, developers

typically use the getAttribute(),

setAttribute(), and

removeAttribute() methods. I will discuss this in

more detail in Chapter 3.

The createDocumentFragment() method will be

discussed in Chapter 8.

You should be aware that a createComment()

method is available for creating comment nodes. It’s not discussed in

this book, but is available to any developer who finds its usage

valuable.

1.8 Using JavaScript Strings to Create and Add Element and Text Nodes to the DOM

The innerHTML, outerHTML,

textContent, and

insertAdjacentHTML() properties and methods provide the

functionality to create and add nodes to the DOM using JavaScript

strings.

In the following code, I am using the innerHTML,

outerHTML, and textContent

properties to create nodes from JavaScript strings that are then

immediately added to the DOM.

<!DOCTYPE html> <html lang="en"> <body> <div id="A"></div> <span id="B"></span> <div id="C"></div> <div id="D"></div> <div id="E"></div> <script> //create a strong element and text node and add it to the DOM document.getElementById('A').innerHTML = '<strong>Hi</strong>'; /* create a div element and text node to replace <span id="B"></div> (notice span#B is replaced) */ document.getElementById('B').outerHTML = '<div id="B" class="new">Whats Shaking</div>' //create a text node and update the div#C with the text node document.getElementById('C').textContent = 'dude'; //NON standard extensions below i.e., innerText and outerText //create a text node and update the div#D with the text node document.getElementById('D').innerText = 'Keep it'; /* create a text node and replace the div#E with the text node (notice div#E is gone) */ document.getElementById('E').outerText = 'real!'; console.log(document.body.innerHTML); /* logs <div id="A"><strong>Hi</strong></div> <div id="B" class="new">Whats Shaking</div> <span id="C">dude</span> <div id="D">Keep it</div> real! */ </script> </body> </html>

The insertAdjacentHTML() method, which only works

on Element nodes, is a good deal more precise than the

previously mentioned methods. Using this method, it’s possible to insert

nodes before the beginning tag, after the beginning tag, before the end

tag, and after the end tag. In the following code, I construct a sentence

using the insertAdjacentHTML()

method.

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html lang="en">

<body><i id="elm">how</i>

<script>

var elm = document.getElementById('elm');

elm.insertAdjacentHTML('beforebegin', '<span>Hey-</span>');

elm.insertAdjacentHTML('afterbegin', '<span>dude-</span>');

elm.insertAdjacentHTML('beforeend', '<span>-are</span>');

elm.insertAdjacentHTML('afterend', '<span>-you?</span>');

console.log(document.body.innerHTML);

/* logs

<span>Hey-</span><i id="A"><span>dude-</span>how<span>-are</span></i><span>-you?</span>

*/

</script>

</body>

</html>Notes

The innerHTML property will convert HTML

elements found in the string to actual DOM nodes, while

textContent can only be used to construct text nodes. If you pass

textContent a string containing HTML elements, it

will simply spit it out as text.

document.write() can also be used to

simultaneously create and add nodes to the DOM. However, it’s typically

not used unless its usage is required to accomplish third-party

scripting tasks. Basically, the write() method will

output to the page the values passed to it during page loading/parsing.

You should be aware that using the write() method

will stall/block the parsing of the HTML document being loaded.

innerHTML invokes a heavy and expensive HTML

parser, whereas text node generation is trivial; thus, use

innerHTML and friends sparingly.

The insertAdjacentHTML options

beforebegin and afterend will only

work if the node is in the DOM tree and has a parent element.

Support for outerHTML was not available

natively in Firefox until version 11. A polyfill is

available.

textContent gets the content of all elements,

including <script> and

<style> elements, but

innerText does not.

innerText is aware of style and will not return

the text of hidden elements, whereas textContent

will.

Available to all modern browsers

except Firefox are insertAdjacentElement() and

insertAdjacentText().

1.9 Extracting Parts of the DOM Tree as JavaScript Strings

Exactly the same properties (innerHTML,

outerHTML, textContent) that we use

to create and add nodes to the DOM can also be used to extract parts of

the DOM (or really, the entire DOM) as a JavaScript string. In the

following code example, I use these properties to return a string value

containing text and HTML values from the HTML document.

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html lang="en">

<body>

<div id="A"><i>Hi</i></div>

<div id="B">Dude<strong> !</strong></div>

<script>

console.log(document.getElementById('A').innerHTML); //logs '<i>Hi</i>'

console.log(document.getElementById('A').outerHTML); /* logs <div id="A">Hi</div> */

/* notice that all text is returned even if it's in child element nodes (i.e., <strong> !</strong>) */

console.log(document.getElementById('B').textContent); //logs 'Dude !'

//NON standard extensions below i.e., innerText and outerText

console.log(document.getElementById('B').innerText); //logs 'Dude !'

console.log(document.getElementById('B').outerText); //logs 'Dude !'

</script>

</body>

</html>Note

The textContent, innerText,

and outerText properties, when being read, will

return all the text nodes contained within the selected node. So, as an

example (note that this is not a good idea in practice),

document.body.textContent will get all the text nodes

contained in the body element, not just the first text node.

1.10 Using appendChild() and insertBefore() to Add Node Objects to the DOM

The appendChild() and

insertBefore() node methods allow us to insert

JavaScript node objects into the DOM tree. The

appendChild() method will append a node (or multiple

nodes) to the end of the child node(s) of the node the method is called

on. If there is no child node(s), the node being appended is appended as

the first child. For example in the following code, I am creating an

element node (<strong>) and a text node

(Dude). Then the <p> element

is selected from the DOM and the <strong> element

is appended using appendChild(). Notice that the

<strong> element is encapsulated inside the

<p> element and added as the last child node.

Next, the <strong> element is selected and the

text Dude is appended to the

<strong> element.

<!DOCTYPE html> <html lang="en"> <body> <p>Hi</p> <script> //create a blink element node and text node var elementNode = document.createElement('strong'); var textNode = document.createTextNode(' Dude'); //append these nodes to the DOM document.querySelector('p').appendChild(elementNode); document.querySelector('strong').appendChild(textNode); //log's <p>Hi<strong> Dude</strong></p> console.log(document.body.innerHTML); </script> </body> </html>

When it becomes necessary to control the location of insertion

beyond appending nodes to the end of a child list of nodes, we can use

insertBefore(). In the following code, I am inserting

the <li> element before the first child node of

the <ul> element.

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html lang="en">

<body>

<ul>

<li>2</li>

<li>3</li>

</ul>

<script>

//create a text node and li element node and append the text to the li

var text1 = document.createTextNode('1');

var li = document.createElement('li');

li.appendChild(text1);

//select the ul in the document

var ul = document.querySelector('ul');

/*

add the li element we created above to the DOM, notice I call on <ul> and pass reference to <li>2</li> using ul.firstChild

*/

ul.insertBefore(li,ul.firstChild);

console.log(document.body.innerHTML);

/*logs

<ul>

<li>1</li>

<li>2</li>

<li>3</li>

</ul>

*/

</script>

</body>

</html>The insertBefore() method requires two

parameters: the node to be inserted and the reference node in the document

before which you would like the node inserted.

Note

If you do not pass a second parameter to the

insertBefore() method, then it functions just like

appendChild().

We have more methods (e.g.,

prepend(), append(),

before(), and after()) to look

forward to in DOM4.

1.11 Using removeChild() and replaceChild() to Remove and Replace Nodes

Removing a node from the DOM is a bit of a multistep process. First

you have to select the node you want to remove. Then you need to gain

access to its parent element, typically by using the

parentNode property. It’s on the parent node that you

invoke the removeChild() method, passing it the

reference to the node to be removed. Here I demonstrate its use on an

element node and a text node.

<!DOCTYPE html> <html lang="en"> <body> <div id="A">Hi</div> <div id="B">Dude</div> <script> //remove element node var divA = document.getElementById('A'); divA.parentNode.removeChild(divA); //remove text node var divB = document.getElementById('B').firstChild; divB.parentNode.removeChild(divB); //log the new DOM updates, which should only show the remaining empty div#B console.log(document.body.innerHTML); </script> </body> </html>

Replacing an element or text node is not unlike removing one. In the

following code, I use the same HTML structure as in the preceding code

example, except this time, I use replaceChild() to

update the nodes instead of removing them.

<!DOCTYPE html> <html lang="en"> <body> <div id="A">Hi</div> <div id="B">Dude</div> <script> //replace element node var divA = document.getElementById('A'); var newSpan = document.createElement('span'); newSpan.textContent = 'Howdy'; divA.parentNode.replaceChild(newSpan,divA); //replace text node var divB = document.getElementById('B').firstChild; var newText = document.createTextNode('buddy'); divB.parentNode.replaceChild(newText, divB); //log the new DOM updates console.log(document.body.innerHTML); </script> </body> </html>

Notes

Depending on what you are removing or replacing, simply providing

the innerHTML, outerHTML, and

textContent properties with an empty string might be

easier and faster. Be careful,

however, as memory leaks in the browser might come back to haunt

you.

replaceChild() and

removeChild() return the replaced and removed node,

respectively. Basically, the node is not gone just because you replace

or remove it. These actions simply take the node out of the current live

document. You still have a reference to it in memory.

We have more methods (e.g.,

replace(), remove()) to look

forward to in DOM4.

1.12 Using cloneNode() to Clone Nodes

Using the cloneNode() method, it’s possible to

duplicate a single node or a node and all its child nodes.

In the following code, I clone only the

<ul> (i.e., HTMLUListElement)

that, once cloned, can be treated like any node reference.

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html lang="en">

<body>

<ul>

<li>Hi</li>

<li>there</li>

</ul>

<script>

var cloneUL = document.querySelector('ul').cloneNode();

console.log(cloneUL.constructor); //logs HTMLUListElement()

console.log(cloneUL.innerHTML); //logs (an empty string) as only the ul was cloned

</script>

</body>

</html>To clone a node and all its child nodes, you pass the

cloneNode() method a parameter of

true. The following code uses the

cloneNode() method again, but this time, I am cloning

all the child nodes as well.

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html lang="en">

<body>

<ul>

<li>Hi</li>

<li>there</li>

</ul>

<script>

var cloneUL = document.querySelector('ul').cloneNode(true);

console.log(cloneUL.constructor); //logs HTMLUListElement()

console.log(cloneUL.innerHTML); //logs <li>Hi</li><li>there</li>

</script>

</body>

</html>Note

When cloning an Element node, all of its

attributes and their values (including in-line events) are cloned as

well. Anything added with addEventListener()

or node.onclick is not cloned.

You might think that cloning a node and its children using

cloneNode(true) would return a

NodeList, but it in fact does not.

cloneNode() may lead to duplicate element IDs

in a document.

1.13 Grokking Node Collections (i.e., NodeList and HTMLCollection)

When selecting groups of nodes from a tree (see Chapter 3) or accessing predefined sets of nodes, the

nodes are placed in either a NodeList

[e.g., document.querySelectorAll('*')] or an HTMLCollection

(e.g., docu). These

array-like object collections have the following characteristics:ment.scripts

A collection can be either live or static. This means the nodes contained in the collection are either literally part of the live document or a snapshot of the live document.

By default, nodes are sorted inside the collection by tree order. This means the order matches the linear path from tree trunk to branches.

The collections have a

lengthproperty that reflects the number of elements in the list.

1.14 Getting a List/Collection of All Immediate Child Nodes

Using the childNodes property produces an

array-like list [i.e., NodeList]

of the immediate child nodes. In the following code, I select the

<ul> element, which I then use to create a list

of all the immediate child nodes contained inside the

<ul>.

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html lang="en">

<body>

<ul>

<li>Hi</li>

<li>there</li>

</ul>

<script>

var ulElementChildNodes = document.querySelector('ul').childNodes;

console.log(ulElementChildNodes); /* logs an arraylike list of all nodes inside of the ul */

/* Call forEach as if it's a method of NodeLists so we can loop over the NodeList. Done because NodeLists are arraylike, but do not directly inherit from Array */

Array.prototype.forEach.call(ulElementChildNodes,function(item){

console.log(item); //logs each item in the array

});

</script>

</body>

</html>1.15 Converting a NodeList or HTMLCollection to a JavaScript Array

Node lists and HTML collections are array-like but are not true

JavaScript arrays, which inherit array methods. In the following code, I

programmatically confirm this using isArray().

<!DOCTYPE html> <html lang="en"> <body> <a href="#"></a> <script> console.log(Array.isArray(document.links)); /* returns false, it's an HTMLCollection not an Array */ console.log(Array.isArray(document.querySelectorAll('a'))); /* returns false, it's a NodeList not an Array */ </script> </body> </html>

Converting a node list and HTML collection list to a true JavaScript

array can provide several benefits. For one, it gives us the ability to

create a snapshot of the list that is not tied to the live DOM,

considering that NodeList and

HTMLCollection are live lists. Second, converting a list

to a JavaScript array gives access to the methods provided by the

Array object (e.g., forEach,

pop, map, reduce,

and so on.).

To convert an array-like list to a true JavaScript array we pass the

array-like list to call() or

apply(), in which the call() or

apply() is calling a method that returns an unaltered

true JavaScript array. In the following code, I use the

.slice() method, which doesn’t really slice anything; I

am just using it to convert the list to a JavaScript

Array since the slice() returns an

array.

<!DOCTYPE html> <html lang="en"> <body> <a href="#"></a> <script> console.log(Array.isArray(Array.prototype.slice.call(document.links))); //returns true console.log(Array.isArray(Array.prototype.slice.call(document.querySelectorAll('a')))); //returns true </script> </body> </html>

1.16 Traversing Nodes in the DOM

From a node reference (i.e.,

document.querySelector('ul')), it’s possible to get a

different node reference by traversing the DOM using the following

properties:

parentNodefirstChildlastChildnextSiblingpreviousSibling

In the following code example, I examine the Node

properties providing DOM traversal functionality.

<!DOCTYPE html> <html lang="en"> <body><ul><!-- comment --> <li id="A"></li> <li id="B"></li> <!-- comment --> </ul> <script> //cache selection of the ul var ul = document.querySelector('ul'); //What is the parentNode of the ul? console.log(ul.parentNode.nodeName); //logs body //What is the first child of the ul? console.log(ul.firstChild.nodeName); //logs comment //What is the last child of the ul? console.log(ul.lastChild.nodeName); /* logs text not comment, because there is a line break */ //What is the nextSibling of the first li? console.log(ul.querySelector('#A').nextSibling.nodeName); //logs text //What is the previousSibling of the last li? console.log(ul.querySelector('#B').previousSibling.nodeName); //logs text </script> </body> </html>

If you are familiar with the DOM, you should not be surprised that traversing the DOM includes traversing not just element nodes, but also text and comment nodes (I believe the preceding code example makes this clear), and this is not exactly ideal. Using the following properties we can traverse the DOM, while ignoring text and comment nodes:

firstElementChildlastElementChildnextElementChildpreviousElementChildchildrenparentElement

Note

The childElementCount is not mentioned, but you

should be aware of its availability for calculating the number of child

elements a node contains.

Let’s examine our code example again using only element traversing methods.

<!DOCTYPE html> <html lang="en"> <body><ul><!-- comment --> <li id="A">foo</li> <li id="B">bar</li> <!-- comment --> </ul> <script> //cache selection of the ul var ul = document.querySelector('ul'); //What is the first child of the ul? console.log(ul.firstElementChild.nodeName); //logs li //What is the last child of the ul? console.log(ul.lastElementChild.nodeName); //logs li //What is the nextSibling of the first li? console.log(ul.querySelector('#A').nextElementSibling.nodeName); //logs li //What is the previousSibling of the last li? console.log(ul.querySelector('#B').previousElementSibling.nodeName); //logs li //What are the element only child nodes of the ul? console.log(ul.children); //HTMLCollection, all child nodes including text nodes //What is the parent element of the first li? console.log(ul.firstElementChild.parentElement); //logs ul </script> </body> </html>

1.17 Verifying a Node Position in the DOM Tree with contains() and compareDocumentPosition()

It’s possible to know whether a node is contained inside another

node by using the contains() node method. In the

following code I ask if <body> is contained

inside <html lang="en">.

<!DOCTYPE html> <html lang="en"> <body> <script> // is <body> inside <html lang="en"> ? var inside = document.querySelector('html').contains(document.querySelector('body')); console.log(inside); //logs true </script> </body> </html>

If you need more robust information about the position of a node in

the DOM tree in regard to the nodes around it, you can use the

compareDocumentPosition() node method. Basically, this

method gives you the ability to request information about a selected node

relative to the node passed in. The information that you get back is a

number that corresponds to the information shown in Table 1-2.

Number code returned from compareDocumentPosition() | Number code information |

0 | Elements are identical. |

1 |

Set when selected node and passed-in node are not in the same document. |

2 |

Set when passed-in node is preceding selected node. |

4 |

Set when passed-in node is following selected node. |

8 |

Set when passed-in node is an ancestor of selected node. |

16, 10 |

Set when passed-in node is a descendant of selected node. |

Notes

contains() will return true

if the node selected and the node passed in are identical.

compareDocumentPosition() can be rather

confusing, because it’s possible for a node to have more than one type

of relationship with another node. For example, when a node both

contains (16) and precedes (4), the returned value from

compareDocumentPosition() will be 20.

1.18 Determining Whether Two Nodes Are Identical

According to the DOM3 specification, two nodes are equal if and only if the following conditions are satisfied:

The two nodes are of the same type.

The following string attributes are equal:

nodeName,localName,namespaceURI,prefix, andnodeValue. That is, they are bothnull, or they have the same length and are identical character for character.The

attributes NamedNodeMapsare equal. That is, they are bothnull, or they have the same length and for each node that exists in one map, there is a node that exists in the other map and is equal, although not necessarily at the same index.The

childNodes NodeListsare equal. That is, they are bothnull, or they have the same length and contain equal nodes at the same index. Note that normalization can affect equality; to avoid this, nodes should be normalized before being compared.

Calling the isEqualNode() method on a node in the

DOM will ask if that node is equal to the node that you pass it as a

parameter. In the following code, I exhibit a case of two identical nodes

and two nodes that do not meet the conditions of being equal to each

other.

<!DOCTYPE html> <html lang="en"> <body> <input type="text"> <input type="text"> <textarea>foo</textarea> <textarea>bar</textarea> <script> //logs true, because they are exactly identical var input = document.querySelectorAll('input'); console.log(input[0].isEqualNode(input[1])); //logs false, because the child text node is not the same var textarea = document.querySelectorAll('textarea'); console.log(textarea[0].isEqualNode(textarea[1])); </script> </body> </html>

Get DOM Enlightenment now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.